Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square (/trəˈfælɡər/ trə-FAL-gər) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, established in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. The square's name commemorates the Battle of Trafalgar, the British naval victory in the Napoleonic Wars over France and Spain that took place on 21 October 1805 off the coast of Cape Trafalgar.

View of the square in 2009 | |

Location within Central London | |

| Former name(s) | Charing Cross |

|---|---|

| Namesake | Battle of Trafalgar |

| Maintained by | Greater London Authority |

| Location | City of Westminster, London, England |

| Postal code | WC2 |

| Coordinates | 51°30′29″N 00°07′41″W |

| North | Charing Cross Road |

| East | The Strand |

| South | Northumberland Avenue Whitehall |

| West | The Mall |

| Construction | |

| Completion | c. 1840 |

| Other | |

| Designer | Sir Charles Barry |

| Website | www |

The site around Trafalgar Square had been a significant landmark since the 1200s. For centuries, distances measured from Charing Cross have served as location markers.[1] The site of the present square formerly contained the elaborately designed, enclosed courtyard, King's Mews. After George IV moved the mews to Buckingham Palace, the area was redeveloped by John Nash, but progress was slow after his death, and the square did not open until 1844. The 169-foot (52 m) Nelson's Column at its centre is guarded by four lion statues. A number of commemorative statues and sculptures occupy the square, but the Fourth Plinth, left empty since 1840, has been host to contemporary art since 1999. Prominent buildings facing the square include the National Gallery, St Martin-in-the-Fields, Canada House, and South Africa House.

The square has been used for community gatherings and political demonstrations, including Bloody Sunday in 1887, the culmination of the first Aldermaston March, anti-war protests, and campaigns against climate change. A Christmas tree has been donated to the square by Norway since 1947 and is erected for twelve days before and after Christmas Day. The square is a centre of annual celebrations on New Year's Eve. It was well known for its feral pigeons until their removal in the early 21st century.

Name

The square is named after the Battle of Trafalgar, a British naval victory in the Napoleonic Wars with France and Spain that took place on 21 October 1805 off the coast of Cape Trafalgar, southwest Spain, although it was not named as such until 1835.[2]

The name "Trafalgar" is a Spanish word of Arabic origin, derived from either Taraf al-Ghar (طرف الغار 'cape of the cave/laurel')[3][4][5] or Taraf al-Gharb (طرف الغرب 'extremity of the west').[6][5]

Geography

Trafalgar Square is owned by the King in Right of the Crown[lower-alpha 1] and managed by the Greater London Authority, while Westminster City Council owns the roads around the square, including the pedestrianised area of the North Terrace.[8] The square contains a large central area with roadways on three sides and a terrace to the north, in front of the National Gallery. The roads around the square form part of the A4, a major road running west of the City of London.[9] Originally having roadways on all four sides, traffic travelled in both directions around the square until a one-way clockwise gyratory system was introduced on 26 April 1926.[10] Works completed in 2003 reduced the width of the roads and closed the northern side to traffic.[11]

Nelson's Column is in the centre of the square, flanked by fountains designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens between 1937 and 1939[12] (replacements for two of Peterhead granite, now in Canada) and guarded by four monumental bronze lions sculpted by Sir Edwin Landseer.[13] At the top of the column is a statue of Horatio Nelson, who commanded the British Navy at the Battle of Trafalgar.

Surrounding the square are the National Gallery on the north side and St Martin-in-the-Fields Church to the east.[13] Also on the east is South Africa House, and facing it across the square is Canada House. To the south west is The Mall, which leads towards Buckingham Palace via Admiralty Arch, while Whitehall is to the south and the Strand to the east. Charing Cross Road passes between the National Gallery and the church.[9]

London Underground's Charing Cross station on the Northern and Bakerloo lines has an exit in the square. The lines had separate stations, of which the Bakerloo line one was called Trafalgar Square until they were linked and renamed in 1979 as part of the construction of the Jubilee line,[14] which was rerouted to Westminster in 1999.[15] Other nearby tube stations are Embankment connecting the District, Circle, Northern and Bakerloo lines, and Leicester Square on the Northern and Piccadilly lines.[16]

London bus routes 3, 6, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 23, 24, 29, 53, 87, 88, 91, 139, 159, 176, 453 are only some among the bus routes that pass through Trafalgar Square.[17]

A point in Trafalgar Square is regarded as the official centre of London in legislation and when measuring distances from the capital.[18]

History

Building work on the south side of the square in the late 1950s revealed deposits from the last interglacial period. Among the findings were the remains of cave lions, rhinoceroses, straight-tusked elephants and hippopotami.[19][20][21]

The site has been significant since the 13th century. During Edward I's reign it hosted the King's Mews, running north from the T-junction in the south, Charing Cross, where the Strand from the City meets Whitehall coming north from Westminster.[2] From the reign of Richard II to that of Henry VII, the mews was at the western end of the Strand. The name "Royal Mews" comes from the practice of keeping hawks here for moulting; "mew" is an old word for this. After a fire in 1534, the mews were rebuilt as stables, and remained here until George IV moved them to Buckingham Palace.[22]

Clearance and development

After 1732, the King's Mews were divided into the Great Mews and the smaller Green Mews to the north by the Crown Stables, a large block, built to the designs of William Kent. Its site is occupied by the National Gallery.[23]

In 1826 the Commissioners of Woods, Forests and Land Revenues instructed John Nash to draw up plans for clearing a large area south of Kent's stable block, and as far east as St Martin's Lane. His plans left open the whole area of what became Trafalgar Square, except for a block in the centre, which he reserved for a new building for the Royal Academy of Arts.[24] The plans included the demolition and redevelopment of buildings between St Martin's Lane and the Strand and the construction of a road (now called Duncannon Street) across the churchyard of St Martin-in-the-Fields.[25] The Charing Cross Act was passed in 1826 and clearance started soon after.[24] Nash died soon after construction started, impeding its progress. The square was to be named for William IV commemorating his ascent to the throne in 1830.[26] Around 1835, it was decided that the square would be named after the Battle of Trafalgar as suggested by architect George Ledwell Taylor, commemorating Nelson's victory over the French and Spanish in 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars.[2][27]

After the clearance, development progressed slowly. The National Gallery was built on the north side between 1832 and 1838 to a design by William Wilkins,[24] and in 1837 the Treasury approved Wilkins' plan for the laying out of the square, but it was not put into effect.[28] In April 1840, following Wilkins' death, new plans by Charles Barry were accepted, and construction started within weeks.[24][29] For Barry, as for Wilkins, a major consideration was increasing the visual impact of the National Gallery, which had been widely criticised for its lack of grandeur. He dealt with the complex sloping site by excavating the main area to the level of the footway between Cockspur Street and the Strand,[30] and constructing a 15-foot (4.6 m) high balustraded terrace with a roadway on the north side, and steps at each end leading to the main level.[29] Wilkins had proposed a similar solution with a central flight of steps.[28] All the stonework was of Aberdeen granite.[29] In 1845, four Bude-Lights with octagonal glass lanterns were installed. Two, opposite the National Gallery, are on tall bronze columns, and two, in the south-west and south-east corners of the square, on shorter bronze columns on top of wider granite columns. They were designed by Barry and manufactured by Stevens and Son, of Southwark.[31]

In 1841 it was decided that two fountains should be included in the layout.[32] The estimated budget, excluding paving and sculptures, was £11,000.[29] The earth removed was used to level Green Park.[30] The square was originally surfaced with tarmacadam, which was replaced with stone in the 1920s.[33]

Trafalgar Square was opened to the public on 1 May 1844.[34]

Nelson's Column

Nelson's Column was planned independently of Barry's work. In 1838 a Nelson Memorial Committee had approached the government proposing that a monument to the victory of Trafalgar, funded by public subscription, should be erected in the square. A competition was held and won by the architect William Railton, who proposed a 218-foot-3-inch (66.52 m) Corinthinan column topped by a statue of Nelson and guarded by four sculpted lions. The design was approved, but received widespread objections from the public. Construction went ahead beginning in 1840 but with the height reduced to 145 feet 3 inches (44.27 m).[35] The column was completed and the statue raised in November 1843.[36]

The last of the bronze reliefs on the column's pedestals was not completed until May 1854, and the four lions, although part of the original design, were only added in 1867.[37] Each lion weighs seven tons.[38] A hoarding remained around the base of Nelson's Column for some years and some of its upper scaffolding remained in place.[39] Landseer, the sculptor, had asked for a lion that had died at the London Zoo to be brought to his studio. He took so long to complete sketches that its corpse began to decompose and some parts had to be improvised. The statues have paws that resemble cats more than lions.[40]

Barry was unhappy about Nelson's Column being placed in the square. In July 1840, when its foundations had been laid, he told a parliamentary select committee that "it would in my opinion be desirable that the area should be wholly free from all insulated objects of art".[29]

In 1940 the Nazi SS developed secret plans to transfer Nelson's Column to Berlin[lower-alpha 2] after an expected German invasion, as related by Norman Longmate in If Britain Had Fallen (1972).[41]

The square has been Grade I listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens since 1996.[42]

Terrorist bombings

The square was the target of two suffragette bombings in 1913 and 1914. This was as part of the suffragette bombing and arson campaign of 1912–1914, in which suffragettes carried out a series of politically-motivated bombing and arson attacks nationwide as part of their campaign for women's suffrage.[43]

The first attack occurred on 15 May 1913. A bomb was planted in the public area outside the National Gallery, but failed to explode.[44] A second attack occurred at St Martin-in-the-Fields church at the north-east corner of the square one 4 April 1914. A bomb exploded inside the church, blowing out the windows and showering passers-by with broken glass. The bomb then started a fire.[45][46] In the aftermath, a mass of people rushed to the scene, many of whom aggressively expressed their anger towards the suffragettes.[45] Churches were a particular target during the campaign, as it was believed that the Church of England was complicit in reinforcing opposition to women's suffrage.[47] Between 1913 and 1914, 32 churches were attacked nationwide.[48] In the weeks after the bombing, there were also attacks on Westminster Abbey and St Paul's Cathedral.[43]

Redevelopment

A major 18-month redevelopment of the square led by W.S. Atkins with Foster and Partners as sub-consultants was completed in 2003. The work involved closing the eastbound road along the north side and diverting traffic around the other three sides of the square, demolishing the central section of the northern retaining wall and inserting a wide set of steps to the pedestrianised terrace in front of the National Gallery. The construction includes two lifts for disabled access, public toilets and a café. Access between the square and the gallery had been by two crossings at the northeast and northwest corners.[49][50]

Statues and monuments

Plinths

Barry's scheme provided two plinths for sculptures on the north side of the square.[51] A bronze equestrian statue of George IV was designed by Sir Francis Chantrey and Thomas Earle. It was originally intended to be placed on top of the Marble Arch, but instead was installed on the eastern plinth in 1843, while the other plinths remained empty until late in the 20th century.[52][24][53] There are two other statues on plinths, both installed during the 19th century: General Sir Charles James Napier by George Cannon Adams in the south-west corner in 1855, and Major-General Sir Henry Havelock by William Behnes in the south-east in 1861.[24] In 2000, the Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, suggested replacing the statues with figures more familiar to the general public.[54]

Fourth plinth

In the 21st century, the empty plinth in the north-west corner of the square, the "Fourth Plinth", has been used to show specially commissioned temporary artworks. The scheme was initiated by the Royal Society of Arts and continued by the Fourth Plinth Commission, appointed by the Mayor of London.[55]

Other sculptures

There are three busts of admirals against the north wall of the square. Those of John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe (by Sir Charles Wheeler) and David Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty (by William MacMillan) were installed in 1948 in conjunction with the square's fountains, which also commemorate them.[56][57] The third, of the Second World War First Sea Lord Andrew Cunningham, 1st Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope (by Franta Belsky) was unveiled alongside them on 2 April 1967.[58]

On the south side of Trafalgar Square, on the site of the original Charing Cross, is a bronze equestrian statue of Charles I by Hubert Le Sueur. It was cast in 1633, and placed in its present position in 1678.[59]

The two statues on the lawn in front of the National Gallery are the statue of James II (designed by Peter van Dievoet[60] and Laurens van der Meulen for the studio of Grinling Gibbons)[61] to the west of the portico, and of one George Washington, a replica of a work by Jean-Antoine Houdon, to the east.[50] The latter was a gift from the Commonwealth of Virginia, installed in 1921.[62]

Two statues erected in the 19th century have since been removed. One of Edward Jenner, pioneer of the smallpox vaccine, was set up in the south-west corner of the square in 1858, next to that of Napier. Sculpted by William Calder Marshall, it showed Jenner sitting in a chair in a relaxed pose, and was inaugurated at a ceremony presided over by Prince Albert. It was moved to Kensington Gardens in 1862.[63][64] The other, of General Charles George Gordon by Hamo Thornycroft, was erected on an 18-foot high pedestal between the fountains in 1888. It was removed in 1943 and re-sited on the Victoria Embankment ten years later.[65]

Fountains

In 1841, following suggestions from the local paving board, Barry agreed that two fountains should be installed to counteract the effects of reflected heat and glare from the asphalt surface. The First Commissioner of Woods and Forests welcomed the plan because the fountains reduced the open space available for public gatherings and reduced the risk of riotous assembly.[66] The fountains were fed from two wells, one in front of the National Gallery and one behind it connected by a tunnel. Water was pumped to the fountains by a steam engine housed in a building behind the gallery.[24]

In the late-1930s it was decided to replace the pump and the centrepieces of the fountains. The new centrepieces, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, were memorials to Lord Jellicoe and Lord Beatty, although busts of the admirals, initially intended to be placed in the fountain surrounds were placed against the northern retaining wall when the project was completed after the Second World War.[67] The fountains cost almost £50,000. The old ones were presented to the Canadian government and are now located in Ottawa's Confederation Park and Regina's Wascana Centre.[68][69]

A programme of restoration was completed by May 2009. The pump system was replaced with one capable of sending an 80-foot (24 m) jet of water into the air.[70] A LED lighting system that can project different combinations of colours on to the fountains was installed to reduce the cost of lighting maintenance and to coincide with the 2012 Summer Olympics.[68]

Pigeons

The square was once famous for feral pigeons and feeding them was a popular activity. Pigeons began flocking to the square before construction was completed and feed sellers became well known in the Victorian era.[71] The desirability of the birds' presence was contentious: their droppings disfigured the stonework and the flock, estimated at its peak to be 35,000, was considered a health hazard.[72][73] A stall seller, Bernie Rayner, infamously sold bird seed to tourists at inflated prices.[74]

In February 2001, the sale of bird seed in the square was stopped[72] and other measures were introduced to discourage the pigeons including the use of birds of prey.[75] Supporters continued to feed the birds but in 2003 the mayor, Ken Livingstone, enacted bylaws to ban feeding them in the square.[76] In September 2007 Westminster City Council passed further bylaws banning feeding birds on the pedestrianised North Terrace and other pavements in the area.[77] Nelson's column was repaired from years of damage from pigeon droppings at a cost of £140,000.[74]

Events

New Year

For many years, revellers celebrating the New Year have gathered in the square despite a lack of celebrations being arranged. The lack of official events was partly because the authorities were concerned that encouraging more partygoers would cause overcrowding. Since 2003, a firework display centred on the London Eye and South Bank of the Thames has been provided as an alternative. Since 2014, New Year celebrations have been organised by the Greater London Authority in conjunction with the charity Unicef, who began ticketing the event to control crowd numbers.[78] The fireworks display has been cancelled during the COVID-19 pandemic, with an event due to take place in the Square to see in 2022.[79] However the event was cancelled during the spread of the SARS-Cov-2 Omicron variant.[80]

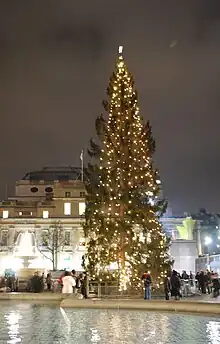

Christmas

A Christmas ceremony has been held in the square every year since 1947.[81] A Norway spruce (or sometimes a fir) is presented by Norway's capital city, Oslo as London's Christmas tree, a token of gratitude for Britain's support during World War II.[81] (Besides war-time support, Norway's Prince Olav and the country's government lived in exile in London throughout the war.[81])

The Christmas tree is decorated with lights that are switched on at a seasonal ceremony.[82] It is usually held twelve days before Christmas Day. The festivity is open to the public and attracts a large number of people.[83] The switch-on is usually followed by several nights of Christmas carol singing and other performances and events.[84] On the twelfth night of Christmas, the tree is taken down for recycling. Westminster City Council threatened to abandon the event to save £5,000 in 1980 but the decision was reversed.[81]

The tree is selected by the Head Forester from Oslo's municipal forest and shipped, across the North Sea to the Port of Felixstowe, then by road to Trafalgar Square. The first tree was 48 feet (15 m) tall, but more recently has been around 75 feet (23 m). In 1987, protesters chained themselves to the tree.[81] In 1990, a man sawed into the tree with a chainsaw a few hours before a New Year's Eve party was scheduled to take place. He was arrested and the tree was repaired by tree surgeons who removed gouged sections from the trunk while the tree was suspended from a crane.[85]

Political demonstrations

The square has become a social and political focus for visitors and Londoners, developing over its history from "an esplanade peopled with figures of national heroes, into the country's foremost place politique", as historian Rodney Mace has written. Since its construction, it has been a venue for political demonstrations.[50] The great Chartist rally in 1848, a campaign for social reform by the working class began in the square.[50] A ban on political rallies remained in effect until the 1880s, when the emerging Labour movement, particularly the Social Democratic Federation, began holding protests. On 8 February 1886 (also known as "Black Monday"), protesters rallied against unemployment leading to a riot in Pall Mall. A larger riot ("Bloody Sunday") occurred in the square on 13 November 1887.[86]

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament's first Aldermaston March, protesting against the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE), began in the square in 1958.[50] One of the first significant demonstrations of the modern era was held in the square on 19 September 1961 by the Committee of 100, which included the philosopher Bertrand Russell. The protesters rallied for peace and against war and nuclear weapons. In March 1968, a crowd of 10,000 demonstrated against US involvement in the Vietnam War before marching to the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square.[87]

Throughout the 1980s, a continuous anti-apartheid protest was held outside South Africa House. In 1990, the Poll Tax Riots began by a demonstration attended by 200,000 people and ultimately caused rioting in the surrounding area.[50] More recently, there have been anti-war demonstrations opposing the Afghanistan War and the Iraq War.[88] A large vigil was held shortly after the terrorist bombings in London on Thursday, 7 July 2005.[89]

In December 2009, participants from the Camp for Climate Action occupied the square for the two weeks during which the UN Conference on Climate Change took place in Copenhagen.[90] It was billed as a UK base for direct action on climate change and saw various actions and protests stem from the occupation.[91][92][93]

In March 2011, the square was occupied by a crowd protesting against the UK Budget and proposed budget cuts. During the night the situation turned violent as the escalation by riot police and protesters damaged portions of the square.[94] In November 2015 a vigil against the terrorist attacks in Paris was held. Crowds sang the French national anthem, La Marseillaise, and held banners in support of the city and country.[95]

Every year on the anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar (21 October), the Sea Cadet Corps holds a parade in honour of Admiral Lord Nelson and the British victory over the combined fleets of Spain and France at Trafalgar.[96] The Royal British Legion holds a Silence in the Square event on Armistice Day, 11 November, in remembrance of those who died in war. The event includes music and poetry readings, culminating in a bugler playing the Last Post and a two-minute silence at 11 am.[97]

In February 2019, hundreds of students participated in a protest against climate change as a part of the School strike for Climate campaign. The protest started in the nearby Parliament Square, and as the day went on, the demonstrators moved towards Trafalgar Square.[98]

In July 2020, two members of the protest group Animal Rebellion were arrested on suspicion for criminal damage after releasing red dye into the fountains.[99][100]

In September 2020 anti-lockdown protests opposed to the imposition of regulations relating to the coronavirus outbreak took place in the square.[101]

A police observation box has been in the Square since 1919, originally a wooden freestanding unit, it was replaced by hollowing out a lampstand at the southeastern corner of the Square into a permanent structure in 1928, but decommissioned in the 1970s.[102]

Sport

In the 21st century, Trafalgar Square has been the location for several sporting events and victory parades. In June 2002, 12,000 people gathered to watch England's FIFA World Cup quarter-final against Brazil on giant video screens which had been erected for the occasion.[103] The square was used by England on 9 December 2003 to celebrate their victory in the Rugby World Cup,[104] and on 13 September 2005 for England's victory in the Ashes series.[105]

On 6 July 2005 Trafalgar Square hosted the official watch party for London's bid to host the 2012 Summer Olympics at the 117th IOC Session in Singapore, hosted by Katy Hill and Margherita Taylor.[106] A countdown clock was erected in March 2011, although engineering and weather-related faults caused it to stop a day later.[107] In 2007, it hosted the opening ceremonies of the Tour de France[108] and was part of the course for subsequent races.[109]

Other uses

The Sea Cadets hold a yearly Battle of Trafalgar victory parade running the north of Whitehall, from Horse Guard's Parade to Nelson's Column.[110]

As an archetypal London location, Trafalgar Square featured in film and television productions during the Swinging London era of the late 1960s, including The Avengers,[111] Casino Royale,[112] Doctor Who,[113] and The Ipcress File.[114] It was used for filming several sketches and a cartoon backdrop in the BBC comedy series Monty Python's Flying Circus.[115] In May 2007, the square was grassed over with 2,000 square metres of turf for two days in a campaign by London authorities to promote "green spaces" in the city.[116]

In July 2011, due to building works in Leicester Square, the world premiere of the final film in the Harry Potter series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2, was held in Trafalgar Square, with a 0.75-mile (1.21 km) red carpet linking the squares. Fans camped in Trafalgar Square for up to three days before the premiere, despite torrential rain. It was the first film premiere ever to be held there.[117]

Cultural references

A Lego architecture set based on Trafalgar Square was released in 2019. It contains models of the National Gallery and Nelson's Column alongside miniature lions, fountains and double-decker buses.[118]

Trafalgar Square is one of the squares on the standard British Monopoly Board. It is in the red set alongside the Strand and Fleet Street.[119]

Several scenes in the dystopian future of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty Four take place in Trafalgar Square, which was renamed "Victory Square" by the story's totalitarian regime and dominated by the giant statue of Big Brother which replaced Nelson.[120]

The square has seen controversy over busking and street theatre, which have attracted complaints over noise and public safety.[121] In 2012, the Greater London Authority created a bylaw for regulating busking and associated tourism.[122][123] In 2016, the National Gallery proposed to introduce licensing for such performances.[124]

Other Trafalgar Squares

A Trafalgar Square in Stepney is recorded in Lockie's Topography of London, published in 1810.[125] Trafalgar Square in Scarborough, North Yorkshire gives its name to the Trafalgar Square End at the town's North Marine Road cricket ground.[126]

The square known as Chelsea Square, London SW3 was at one time known as Trafalgar Square and predated the one in Westminster.[127]

National Heroes Square in Bridgetown, Barbados, was named Trafalgar Square in 1813, before its better-known British namesake. It was renamed in 1999 to commemorate national heroes of Barbados.[128] There is a life scale replica of the square in Bahria Town, Lahore, Pakistan where it is a tourist attraction and centre for local residents.[129]

See also

- Canada House

- Parliament Square

- South Africa House

- Bloody Sunday (1887) – riots focused on Trafalgar Square.

- List of public art in Trafalgar Square and the vicinity

References

Notes

- "King in Right of the Crown" is legal fiction denoting the land is privately owned by the King and it is legally possible, though unlikely, to be sold to another individual. The Crown Jewels are under similar ownership.[7]

- Hitler had specifically requested that all of Rembrandt's paintings in the National Gallery be seized as part of the move, as he particularly admired the artist's work.[41]

Citations

- BBC. "Where Is The Centre Of London?". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 934.

- "2". 15 December 2004. Archived from the original on 15 December 2004.

- Entry algar, in DRAE dictionary

- Richard Burton. "The Arabian Nights". footnote 82.

- Joseph E. Garreau. "A Cultural Introduction to the Languages of Europe". Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "The convenient fiction of who owns priceless treasure". The Guardian. 30 May 2002. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- "Trafalgar Square". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 27 November 2003. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Trafalgar Square". Google Maps. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- "Trafalgar Square Traffic". The Times. No. 44253. 23 April 1926. p. 11. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "TRAVEL ADVISORY; Boon to Pedestrians In Central London". The New York Times. 3 August 2003. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- Barker 2005, p. 43.

- Thornbury, Walter (1878). Trafalgar Square and the National Gallery. pp. 141–149. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Clayton, Antony (2000). Subterranean City: Beneath the Streets of London. Historical Publications. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-948667-69-5.

- "Take a behind-the-scenes tour of the disused parts of Charing Cross tube station". Time Out. 16 April 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- "Standard tube map" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- "Central London Bus Map" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- Where Is The Centre Of London? Archived 17 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine BBC

- Sutcliffe, A.J. (1985). On the track of Ice Age mammals. Harvard University Press. pp. 139. ISBN 978-0674637771.

- Franks, J.W. (1960). "Interglacial deposits at Trafalgar Square, London". The New Phytologist. 59 (2): 145–150. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1960.tb06212.x. JSTOR 2429192.

- J W Franks (9 September 1959). "Interglacial Deposits at Trafalgar Square, London". New Phytologist. 59 (2): 145–152. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1960.tb06212.x.

- "The History of the Royal Mews". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Mace 1976, p. 29.

- G. H. Gater (1940). F. R. Hiorns (ed.). "Trafalgar Square and the National Gallery". Survey of London. 20: St Martin-in-the-Fields, pt III: Trafalgar Square & Neighbourhood: 15–18. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- Mace 1976, p. 37.

- Moore 2003, p. 176.

- Cardinal, Marc (2010). Wanderlust: Based on the true-life journals of Sydney Taylor. AuthorHouse. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-4490-7907-9.

- "Design for a national Naval Monument". The Architectural Magazine and Journal. 4: 524. 1837. quoting the ' 'Observer' ' of 24 September 1837

- Report from the Select Committee on Trafalgar Square together with the Minutes of Evidence, Printed by the House of Commons, 1840, retrieved 6 October 2011

- "Public Buildings &c Trafalgar Square". The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal. 3: 255. 1840.

- "The Bude Lights, Trafalgar-Square". The Illustrated London News. Vol. 6. 3 May 1845. p. 284.

- Mace 1976, p. 107.

- Bradley, Simon; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2003). London 6: Westminster. The Buildings of England. Yale University Press.

- Cunningham, Peter (1849). "London Occurrences 1837–1843". Handbook of London Past and Present. London: John Murray. p. lxv. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Moore 2003, p. 177.

- Mace 1976, p. 90.

- Mace 1976, pp. 107–8.

- Bow Bells – A Magazine of General Literature, John Dicks, 1867, archived from the original on 2 April 2017, retrieved 31 March 2017

- "Opening of Trafalgar Square". The Times. 31 July 1839. p. 6.

- "The faulty lions of Trafalgar Square". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Longmate 2012, p. 137.

- Historic England, "Trafalgar Square (1001362)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 11 July 2017

- "Suffragettes, violence and militancy". British Library. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- Webb, Simon (2014). The Suffragette Bombers: Britain's Forgotten Terrorists. Pen and Sword. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-78340-064-5.

- Webb, Simon (2014). The Suffragette Bombers: Britain's Forgotten Terrorists. Pen and Sword. p. xiii. ISBN 978-1-78340-064-5.

- Bearman, C. J. (2005). "An Examination of Suffragette Violence". The English Historical Review. 120 (486): 391. doi:10.1093/ehr/cei119. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 3490924.

- Webb, Simon (2014). The Suffragette Bombers: Britain's Forgotten Terrorists. Pen and Sword. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-78340-064-5.

- Bearman, C. J. (2005). "An Examination of Suffragette Violence". The English Historical Review. 120 (486): 378. doi:10.1093/ehr/cei119. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 3490924.

- "Trafalgar Square redevelopment". Foster+Partners. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 935.

- "Suggestions for Trafalgar Square's Vacant Plinth". Government News. 27 December 1999. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1275350)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- Macintyre, James (23 October 2011). "From Beckham to Lapper, the ever-changing cast". The Independent. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- Paul Kelso (20 October 2000). "Mayor attacks generals in battle of Trafalgar Square". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- "Fourth Plinth". Greater London Council. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- Baker, Margatet (2008), Discovering London Statues and Monuments, Osprey Publishing, p. 9

- "McMillan, William (1887–1977)". Your Archives, The National Archives. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- Bust of Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope by Franta Belsky, Your Archives, The National Archives, archived from the original on 24 February 2013, retrieved 27 November 2007

- John Gorton: A Topographical Dictionary of Great Britain and Ireland, 1833, p. 687

- "Artistes, de père en fils". Site-LeVif-FR. 21 November 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Horace Walpole, Anecdotes of painting in England: with some account of the principal artists; and incidental notes on other arts; collected by the late Mr. George Vertue; and now digested and published from his original MSS. by Mr. Horace Walpole, London, 1765, vol. III, p. 91 : « Gibbons had several disciples and workmen; Selden I have mentioned; Watson assisted chiefly at Chatsworth, where the boys and many of the ornaments in the chapel were executed by him. Dievot of Brussels, and Laurens of Mechlin were principal journeymen — Vertue says they modelled and cast the statue I have mentioned in the privy-garden ». According to David Green, in Grinling Gibbons, his work as carver and statuary (London, 1964), one Smooke sayd to Vertue that this statue "was modelled and made by Laurence and Devoot (sic)"; George Vertue, Note Books, ed. Walpole Society, Oxford, 1930–47, vol. I, p.82 : "Lawrence. Dyvoet. statuarys", and ibidem IV, 50 : "Laurens a statuary of Mechlin... Dievot a statuary of Brussels both these artists were in England and assisted Mr. Gibbons in statuary works in K. Charles 2d. and K. James 2d. time, they left England in the troubles of the Revolution and retird to their own country".

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 875.

- "The Jenner Monument". Dublin Hospital Gazette. 5: 176. 1858.

- Edward Walford (1878). "Kensington Gardens". Old and New London: Volume 5. Institute of Historical Research. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- Mace 1976, pp. 125–126.

- Mace 1976, p. 87.

- Mace 1976, pp. 130–1.

- Kennedy, Maev (29 May 2009), "Trafalgar Square fountain spurts to new heights", The Guardian, London, archived from the original on 15 July 2014, retrieved 25 May 2010

- "Trafalgar Square fountains". 2003. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- Kennedy, Maev (29 May 2009). "Trafalgar Square fountain spurts to new heights". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- Moore 2003, p. 181.

- "Pigeon feed seller takes flight", BBC News, 7 February 2001, archived from the original on 8 August 2017, retrieved 30 April 2013

- Jones, Richard (2015). House Guests, House Pests: A Natural History of Animals in the Home. Bloomsbury. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4729-0624-3.

- McSmith, Andy (23 October 2011). "The pigeons have gone, but visitors are flocking to Trafalgar Square". The Independent. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Bird control contractor appointed in 2004 to deter pigeons from Trafalgar Square, vvenv.co.uk, 8 October 2004, archived from the original on 25 April 2012, retrieved 19 October 2011

- "Feeding Trafalgar's pigeons illegal". BBC News. 17 November 2003. Archived from the original on 15 March 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Pigeon feeding banned in Trafalgar Square, 24dash.com, 10 September 2007, archived from the original on 29 June 2012, retrieved 17 September 2007

- "London New Year's Eve with Unicef". Greater London Authority. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- "London New Year fireworks replaced by Trafalgar Square event". BBC News. 19 November 2021.

- "Omicron: Trafalgar Square New Year's Eve event cancelled". BBC News. 20 December 2021.

- "Shedding light on Christmas". BBC News. 21 December 1997. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- "Trafalgar Square tree lighting ceremony". Met Office. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- "Trafalgar Square sparkles blue as Christmas tree lights go on". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "Christmas in Trafalgar Square". Greater London Council. 5 November 2015. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- "Man Takes Chain Saw to Trafalgar Square Tree, but Tannenbaum Stands". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 31 December 1990. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Crick 1994, p. 47.

- "On This Day – 17 March – 1968: Anti-Vietnam demo turns violent". bbc.co.uk. BBC News. 2008. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- Keith Flett (8 January 2005), "The Committee of 100: Sparking a new left", Socialist Worker (1933), archived from the original on 21 March 2006, retrieved 10 March 2006

- "London falls silent for bomb dead", BBC News, 14 July 2005, archived from the original on 22 July 2006, retrieved 22 June 2007

- "COP OUT CAMP OUT Âť Camp for Climate Action". Climatecamp.org.uk. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "UK Indymedia – Climate protestors scale Canadian Embassy and deface flag". Indymedia.org.uk. 15 December 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "UK Indymedia – Climate Camp Trafalgar- Ice Bear action". Indymedia.org.uk. 18 December 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "UK Indymedia – Thur Dec 17 protest outside Danish Embassy, London". Indymedia.org.uk. 17 December 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Wikinews:Battle for Trafalgar Square, London as violence breaks out between demonstrators and riot police

- "Paris terror attacks". The Independent. 14 November 2015. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "Sea Cadets in Battle of Trafalgar parade". The Daily Telegraph. 21 October 2012. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- "Armistice Day: Nation remembers war dead". BBC News. 11 November 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- "School children across UK strike over climate change". Sky News. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- "Trafalgar Square fountains: Two arrested over red dye protest". BBC News. 11 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Vegan activists turn Trafalgar Square fountains blood red". Metro. 11 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Coronavirus: London anti-lockdown protests see 16 arrests as police left in hospital after clashes". Sky News.

- "Trafalgar Square's "police station" isn't what it's claimed to be". ianVisits. 8 April 2018.

- "England fans mourn defeat", BBC News, 21 June 2002, archived from the original on 8 April 2008, retrieved 24 May 2007

- "England honours World Cup stars". BBC Sport. 9 December 2003. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "Fans hail England's Ashes heroes". BBC News. 13 September 2005. Archived from the original on 10 September 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "2005: London to host 2012 Olympics". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Magnay, Jacquelin (15 March 2011). "London 2012 Olympics: Trafalgar Square countdown clock stops". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- "Crowds turn out for Tour opening". BBC News. 6 July 2007. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- "London gets ready to welcome back the Tour de France on Monday". Transport For London. 4 July 2014. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- "Sea Cadets in Battle of Trafalgar parade". The Daily Telegraph. 21 October 2012. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- Chapman, James (2002). Saints and Avengers: British Adventure Series of the 1960s. I.B.Tauris. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-86064-753-6.

- Burlingame, Jon (2012). The Music of James Bond. Oxford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-19-986330-3.

- Muir, John Kenneth (1999). A Critical History of Doctor Who on Television. McFarland. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-7864-3716-0.

- James, Simon (2007). London Film Location Guide. Anova Books. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-7134-9062-6.

- Larsen 2008, p. 203.

- "Trafalgar Square green with turf", BBC News, 24 May 2007, archived from the original on 27 August 2017, retrieved 18 December 2015

- Masters, Tim (7 July 2011). "Harry Potter premiere: Stars and fans bid tearful goodbye". BBC Entertainment & Arts. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- "Lego's Next Architecture Set Will Be London's Trafalgar Square". Arch Daily. 11 April 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Moore 2003, p. 185.

- Gordon Bowker (23 September 2010). "Gordon Bowker Orwell's London". The Orwell Foundation. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Buskers in the West End could need licences after outcry at noise". London Evening Standard. 30 November 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Odih 2019, p. 346.

- Trafalgar Square Byelaws (PDF). Greater London Council (Report). 2012. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "National Gallery plans to demand Trafalgar Square buskers leave so it can create 'one of London's great parks'". The Independent. 16 February 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Lockie, John (1810). Lockie's Topography of London and its Environs. London.

- "Ground Development". Scarborough Cricket Club. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- "London's Other Trafalgar Square". 30 May 2017.

- Whiting, Keith (2012). Barbados Adventure Guides Series. Hunter Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-58843-652-8.

- "Safe Behind Their Walls". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

Sources

- Barker, Michael (2005). Sir Edwin Lutyens. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7478-0582-3.

- Crick, Martin (1994). The History of the Social-Democratic Federation. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-85331-091-1.

- Larsen, Darl (2008). Monty Python's Flying Circus: An Utterly Complete, Thoroughly Unillustrated, Absolutely Unauthorized Guide to Possibly All the References. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-6131-2.

- Longmate, Norman (2012). If Britain Had Fallen: The Real Nazi Occupation Plans (reprinted / illustrated ed.). Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-84832-647-7.

- Mace, Rodney (1976). Trafalgar Square: Emblem of Empire. London: Lawrence and Wishart. ISBN 978-0-85315-368-9. Second edition published as Mace, Rodney (2005). Trafalgar Square: Emblem of Empire (2nd ed.). London: Lawrence and Wishart. ISBN 978-1-905007-11-0.

- Moore, Tim (2003). Do Not Pass Go. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-943386-6.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, Julia; Keay, John (2008). The London Encyclopedia. Pan MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-4924-5.

- Odih, Pamela (2019). Adsensory Urban Ecology Volume Two. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-2468-2.

Further reading

- "Fourth Plinth". blitzandblight.com. 12 February 2007. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Hackman, Gill (2014). Stone to Build London: Portland's Legacy. Monkton Farleigh: Folly Books. ISBN 978-0-9564405-9-4. OCLC 910854593. Book includes details of the Portland stone buildings around Trafalgar Square, including St Martin in the Fields, the National Gallery and Admiralty Arch.

- Hargreaves, Roger (2005). Trafalgar Square: Through the Camera. London: National Portrait Gallery Publications. ISBN 978-1-85514-345-6.

- Holt, Gavin (1934). Trafalgar Square. London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 220695363.

- Hood, Jean (2005). Trafalgar Square: A Visual History of London's Landmark through Time. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-8967-5.

.jpg.webp)