London Bridge

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. It is the oldest road-crossing location on the river. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It replaced a 19th-century stone-arched bridge, which in turn superseded a 600-year-old stone-built medieval structure. In addition to the roadway, for much of its history, the broad medieval bridge supported an extensive built up area of homes and businesses part of the City's Bridge Ward and its southern end in Southwark was guarded by a large stone City gateway. The medieval bridge was preceded by a succession of timber bridges, the first of which was built by the Roman founders of London (Londinium) around 50 AD.

London Bridge | |

|---|---|

London Bridge in 2017 | |

| Coordinates | 51°30′29″N 0°05′16″W |

| Carries | Five lanes of the A3 |

| Crosses | River Thames |

| Locale | Central London |

| Maintained by | Bridge House Estates, City of London Corporation |

| Preceded by | Cannon Street Railway Bridge |

| Followed by | Tower Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Prestressed concrete box girder bridge |

| Total length | 269 m (882.5 ft) |

| Width | 32 m (105.0 ft) |

| Longest span | 104 m (341.2 ft) |

| Clearance below | 8.9 m (29.2 ft) |

| Design life |

|

| History | |

| Opened | 16 March 1973 |

| Location | |

The current bridge stands at the western end of the Pool of London and is positioned 30 metres (98 ft) upstream from previous alignments. The approaches to the medieval bridge were marked by the church of St Magnus-the-Martyr on the northern bank and by Southwark Cathedral on the southern shore. Until Putney Bridge opened in 1729, London Bridge was the only road crossing of the Thames downstream of Kingston upon Thames. London Bridge has been depicted in its several forms, in art, literature, and songs, including the nursery rhyme "London Bridge Is Falling Down", and the epic poem The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot.

The modern bridge is owned and maintained by Bridge House Estates, an independent charity of medieval origin overseen by the City of London Corporation. It carries the A3 road, which is maintained by the Greater London Authority.[1] The crossing also delineates an area along the southern bank of the River Thames, between London Bridge and Tower Bridge, that has been designated as a business improvement district.[2]

History

Location

The abutments of modern London Bridge rest several metres above natural embankments of gravel, sand and clay. From the late Neolithic era the southern embankment formed a natural causeway above the surrounding swamp and marsh of the river's estuary; the northern ascended to higher ground at the present site of Cornhill. Between the embankments, the River Thames could have been crossed by ford when the tide was low, or ferry when it was high. Both embankments, particularly the northern, would have offered stable beachheads for boat traffic up and downstream – the Thames and its estuary were a major inland and Continental trade route from at least the 9th century BC.[3]

There is archaeological evidence for scattered Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age settlement nearby, but until a bridge was built there, London did not exist.[4] A few miles upstream, beyond the river's upper tidal reach, two ancient fords were in use. These were apparently aligned with the course of Watling Street, which led into the heartlands of the Catuvellauni, Britain's most powerful tribe at the time of Caesar's invasion of 54 BC. Some time before Claudius's conquest of AD 43, power shifted to the Trinovantes, who held the region northeast of the Thames Estuary from a capital at Camulodunum, nowadays Colchester in Essex. Claudius imposed a major colonia at Camulodunum, and made it the capital city of the new Roman province of Britannia. The first London Bridge was built by the Romans as part of their road-building programme, to help consolidate their conquest.[5]

Roman bridges

It is possible that Roman military engineers built a pontoon type bridge at the site during the conquest period (AD 43). A bridge of any kind would have given a rapid overland shortcut to Camulodunum from the southern and Kentish ports, along the Roman roads of Stane Street and Watling Street (now the A2). The Roman roads leading to and from London were probably built around AD 50, and the river-crossing was possibly served by a permanent timber bridge.[6] On the relatively high, dry ground at the northern end of the bridge, a small, opportunistic trading and shipping settlement took root and grew into the town of Londinium.[7] A smaller settlement developed at the southern end of the bridge, in the area now known as Southwark. The bridge may have been destroyed along with the town in the Boudican revolt (AD 60), but Londinium was rebuilt and eventually, became the administrative and mercantile capital of Roman Britain. The bridge offered uninterrupted, mass movement of foot, horse, and wheeled traffic across the Thames, linking four major arterial road systems north of the Thames with four to the south. Just downstream of the bridge were substantial quays and depots, convenient to seagoing trade between Britain and the rest of the Roman Empire.[8][9]

Early medieval bridges

With the end of Roman rule in Britain in the early 5th century, Londinium was gradually abandoned and the bridge fell into disrepair. In the Anglo-Saxon period, the river became a boundary between the emergent, mutually hostile kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex. By the late 9th century, Danish invasions prompted at least a partial reoccupation of the site by the Saxons. The bridge may have been rebuilt by Alfred the Great soon after the Battle of Edington as part of Alfred's redevelopment of the area in his system of burhs,[10] or it may have been rebuilt around 990 under the Saxon king Æthelred the Unready to hasten his troop movements against Sweyn Forkbeard, father of Cnut the Great. A skaldic tradition describes the bridge's destruction in 1014 by Æthelred's ally Olaf,[11] to divide the Danish forces who held both the walled City of London and Southwark. The earliest contemporary written reference to a Saxon bridge is c. 1016 when chroniclers mention how Cnut's ships bypassed the crossing, during his war to regain the throne from Edmund Ironside.[12]

Following the Norman conquest in 1066, King William I rebuilt the bridge. It was repaired or replaced by King William II, destroyed by fire in 1136, and rebuilt in the reign of Stephen. Henry II created a monastic guild, the "Brethren of the Bridge", to oversee all work on London Bridge. In 1163, Peter of Colechurch, chaplain and warden of the bridge and its brethren, supervised the bridge's last rebuilding in timber.[13]

Old London Bridge (1209–1831)

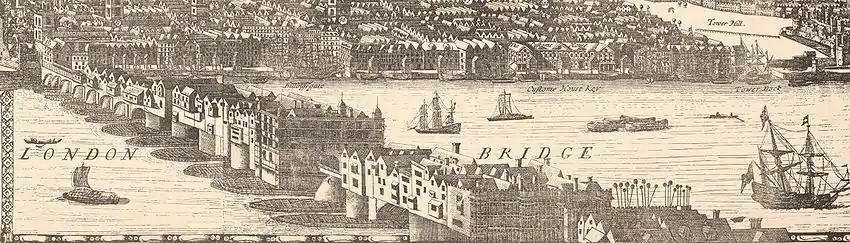

_by_Claes_Van_Visscher.jpg.webp)

After the murder of his former friend and later opponent Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, the penitent King Henry II commissioned a new stone bridge in place of the old, with a chapel at its centre dedicated to Becket as martyr. The archbishop had been a native Londoner, born at Cheapside, and a popular figure. The Chapel of St Thomas on the Bridge became the official start of pilgrimage to his Canterbury shrine; it was grander than some town parish churches, and had an additional river-level entrance for fishermen and ferrymen. Building work began in 1176, supervised by Peter of Colechurch.[13] The costs would have been enormous; Henry's attempt to meet them with taxes on wool and sheepskins probably gave rise to a later legend that London Bridge was built on wool packs.[13] In 1202, before Colechurch's death, Isembert, a French monk who was renowned as a bridge builder, was appointed by King John to complete the project. Construction was not finished until 1209. There were houses on the bridge from the start; this was a normal way of paying for the maintenance of a bridge, though in this case it had to be supplemented by other rents and by tolls. From 1282 two bridge wardens were responsible for maintaining the bridge, heading the organization known as the Bridge House. The only two collapses occurred when maintenance had been neglected, in 1281 (five arches) and 1437 (two arches). In 1212, perhaps the greatest of the early fires of London broke out, spreading as far as the chapel and trapping many people.

The bridge was about 926 feet (282 metres) long, and had nineteen piers linked by nineteen arches and a wooden drawbridge. There were 'starlings' around the piers to protect them (they had deeper piles than the piers themselves). The bridge, including the part occupied by houses, was from 20 to 24 feet (6.1 to 7.3 metres) wide. The roadway was mostly around 15 feet (4.6 metres) wide, varying from about 14 feet to 16 feet, except that it was narrower at defensive features (the stone gate, the drawbridge and the drawbridge tower) and wider south of the stone gate. The houses occupied only a few feet on each side of the bridge. They received their main support either from the piers, which extended well beyond the bridge itself from west to east, or from 'hammer beams' laid from pier to pier parallel to the bridge. It was the length of the piers which made it possible to build quite large houses, up to 34 feet (10 metres) deep.[14]

The numerous starlings restricted the river's tidal ebb and flow. The difference in water levels on the two sides of the bridge could be as much as 6 feet (1.8 m), producing ferocious rapids between the piers resembling a weir.[15] Only the brave or foolhardy attempted to "shoot the bridge" – steer a boat between the starlings when in flood – and some were drowned in the attempt. The bridge was "for wise men to pass over, and for fools to pass under."[16] The restricted flow also meant that in hard winters the river upstream was more susceptible to freezing.

The number of houses on the bridge reached its maximum in the late fourteenth century, when there were 140. Subsequently, many of the houses, originally only 10 to 11 feet wide, were merged, so that by 1605 there were 91. Originally they are likely to have had only two storeys, but they were gradually enlarged. In the seventeenth century, when there are detailed descriptions of them, almost all had four or five storeys (counting the garrets as a storey); three houses had six storeys. Two-thirds of the houses were rebuilt from 1477 to 1548. In the seventeenth century, the usual plan was a shop on the ground floor, a hall and often a chamber on the first floor, a kitchen and usually a chamber and a waterhouse (for hauling up water in buckets) on the second floor, and chambers and garrets above. Approximately every other house shared in a 'cross building' above the roadway, linking the houses either side and extending from the first floor upwards.[17]

All the houses were shops, and the bridge was one of the City of London's four or five main shopping streets. There seems to have been a deliberate attempt to attract the more prestigious trades. In the late fourteenth century more than four-fifths of the shopkeepers were haberdashers, glovers, cutlers, bowyers and fletchers or from related trades. By 1600 all of these had dwindled except the haberdashers, and the spaces were filled by additional haberdashers, by traders selling textiles and by grocers. From the late seventeenth century there was a greater variety of trades, including metalworkers such as pinmakers and needle makers, sellers of durable goods such as trunks and brushes, booksellers and stationers.[18]

The three major buildings on the bridge were the chapel, the drawbridge tower and the stone gate, all of which seem to have been present soon after the bridge's construction. The chapel was last rebuilt in 1387–1396, by Henry Yevele, master mason to the king. Following the Reformation, it was converted into a house in 1553. The drawbridge tower was where the severed heads of traitors were exhibited. The drawbridge ceased to be opened in the 1470s and in 1577–1579 the tower was replaced by Nonsuch House—a pair of magnificent houses. Its architect was Lewis Stockett, Surveyor of the Queen's Works, who gave it the second classical facade in London (after Somerset House in the Strand). The stone gate was last rebuilt in the 1470s, and later took over the function of displaying the heads of traitors.[19] The heads were dipped in tar and boiled to preserve them against the elements, and were impaled on pikes.[20] The head of William Wallace was the first recorded as appearing, in 1305, starting a long tradition. Other famous heads on pikes included those of Jack Cade in 1450, Thomas More in 1535, Bishop John Fisher in the same year, and Thomas Cromwell in 1540. In 1598, a German visitor to London, Paul Hentzner, counted over 30 heads on the bridge:[21]

On the south is a bridge of stone eight hundred feet in length, of wonderful work; it is supported upon twenty piers of square stone, sixty feet high and thirty broad, joined by arches of about twenty feet diameter. The whole is covered on each side with houses so disposed as to have the appearance of a continued street, not at all of a bridge. Upon this is built a tower, on whose top the heads of such as have been executed for high treason are placed on iron spikes: we counted above thirty.

The last head was installed in 1661;[22] subsequently heads were placed on Temple Bar instead, until the practice ceased.[23]

There were two multi-seated public latrines, but they seem to have been at the two ends of the bridge, possibly on the riverbank. The one at the north end had two entrances in 1306. In 1481, one of the latrines fell into the Thames and five men were drowned. Neither of the latrines is recorded after 1591.[24]

In 1578–1582 a Dutchman, Peter Morris, created a waterworks at the north end of the bridge. Water wheels under the two northernmost arches drove pumps that raised water to the top of a tower, from which wooden pipes conveyed it into the city. In 1591 water wheels were installed at the south end of the bridge to grind corn.[25]

In 1633 fire destroyed the houses on the northern part of the bridge. The gap was only partly filled by new houses, with the result that there was a firebreak that prevented the Great Fire of London (1666) spreading to the rest of the bridge and to Southwark. The Great Fire destroyed the bridge's waterwheels, preventing them from pumping water to fight the fire.

For nearly 20 years only sheds replaced the burnt buildings. They were replaced In the 1680s, when almost all the houses on the bridge were rebuilt. The roadway was widened to 20 feet (6.1 metres) by setting the houses further back and was increased in height from one storey to two. The new houses extended further back over the river, which was to cause trouble later. In 1695 the bridge had 551 inhabitants. From 1670 attempts were made to keep traffic in each direction to one side, at first through a keep-right policy and from 1722 through a keep-left policy.[26] This has been suggested as one possible origin for the practice of traffic in Britain driving on the left.[27]

| London Bridge Act 1756 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An Act to improve, widen, and enlarge, the Passage over and through London Bridge. |

| Citation | 29 Geo. 2. c. 40 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 27 May 1756 |

A fire in September 1725 destroyed all the houses south of the stone gate; they were rebuilt.[28] The last houses to be built on the bridge were designed by George Dance the Elder in 1745,[29] but these buildings had begun to subside within a decade.[30] The London Bridge Act 1756 (29 Geo. 2. c. 40) gave the City Corporation the power to purchase all the properties on the bridge so that they could be demolished and the bridge improved. While this work was underway, a temporary wooden bridge was constructed to the west of London Bridge. It opened in October 1757 but caught fire and collapsed in the following April. The old bridge was reopened until a new wooden construction could be completed a year later.[31] To help improve navigation under the bridge, its two centre arches were replaced by a single wider span, the Great Arch, in 1759.

Demolition of the houses was completed in 1761 and the last tenant departed after some 550 years of housing on the bridge.[32] Under the supervision of Dance the Elder, the roadway was widened to 46 feet (14 m)[33] and a balustrade was added "in the Gothic taste" together with 14 stone alcoves for pedestrians to shelter in.[34] However, the creation of the Great Arch had weakened the rest of the structure and constant expensive repairs were required in the following decades; this, combined with congestion both on and under bridge, often leading to fatal accidents, resulted in public pressure for a modern replacement.[35]

London Bridge from Pepper Alley Stairs by Herbert Pugh, showing the appearance of London Bridge after 1762, with the new "Great Arch" at the centre

London Bridge from Pepper Alley Stairs by Herbert Pugh, showing the appearance of London Bridge after 1762, with the new "Great Arch" at the centre Old London Bridge by J. M. W. Turner, showing the new balustrade and the back of one of the pedestrian alcoves

Old London Bridge by J. M. W. Turner, showing the new balustrade and the back of one of the pedestrian alcoves One of the pedestrian alcoves from the 1762 renovation, now in Victoria Park, Tower Hamlets – a similar alcove from the same source can be seen at the Guy's Campus of King's College London

One of the pedestrian alcoves from the 1762 renovation, now in Victoria Park, Tower Hamlets – a similar alcove from the same source can be seen at the Guy's Campus of King's College London A section of balustrade from London Bridge, now at Gilwell Park in Essex

A section of balustrade from London Bridge, now at Gilwell Park in Essex.jpg.webp) A relief of the Hanoverian Royal Arms from a gateway over the old London Bridge now forms part of the façade of the King's Arms pub, Southwark

A relief of the Hanoverian Royal Arms from a gateway over the old London Bridge now forms part of the façade of the King's Arms pub, Southwark

New London Bridge (1831–1967)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

In 1799, a competition was opened to design a replacement for the medieval bridge. Entrants included Thomas Telford; he proposed a single iron arch span of 600 feet (180 m), with 65 feet (20 m) centre clearance beneath it for masted river traffic. His design was accepted as safe and practicable, following expert testimony.[36] Preliminary surveys and works were begun, but Telford's design required exceptionally wide approaches and the extensive use of multiple, steeply inclined planes, which would have required the purchase and demolition of valuable adjacent properties.[37]

A more conventional design of five stone arches, by John Rennie, was chosen instead. It was built 100 feet (30 m) west (upstream) of the original site by Jolliffe and Banks of Merstham, Surrey,[38] under the supervision of Rennie's son. Work began in 1824 and the foundation stone was laid, in the southern coffer dam, on 15 June 1825.

.jpg.webp)

The old bridge continued in use while the new bridge was being built, and was demolished after the latter opened in 1831. New approach roads had to be built, which cost three times as much as the bridge itself. The total costs, around £2.5 million (£242 million in 2021),[39] were shared by the British Government and the Corporation of London.

Rennie's bridge was 928 feet (283 m) long and 49 feet (15 m) wide, constructed from Haytor granite. The official opening took place on 1 August 1831; King William IV and Queen Adelaide attended a banquet in a pavilion erected on the bridge. The northern approach road, King William Street, was renamed after the monarch.

In 1896 the bridge was the busiest point in London, and one of its most congested; 8,000 pedestrians and 900 vehicles crossed every hour.[20] It was widened by 13 feet (4.0 m), using granite corbels.[40] Subsequent surveys showed that the bridge was sinking an inch (about 2.5 cm) every eight years, and by 1924 the east side had sunk some three to four inches (about 9 cm) lower than the west side. The bridge would have to be removed and replaced.

Sale to Robert McCulloch

Common Council of the City of London member Ivan Luckin put forward the idea of selling the bridge, and recalled: "They all thought I was completely crazy when I suggested we should sell London Bridge when it needed replacing."[41] Subsequently, in 1968, Council placed the bridge on the market and began to look for potential buyers. On 18 April 1968, Rennie's bridge was purchased by the Missourian entrepreneur Robert P. McCulloch of McCulloch Oil for US$2,460,000. The claim that McCulloch believed mistakenly that he was buying the more impressive Tower Bridge was denied by Luckin in a newspaper interview.[42] Before the bridge was taken apart, each granite facing block was marked for later reassembly.

.jpg.webp)

The blocks were taken to Merrivale Quarry at Princetown in Devon, where 15 to 20 cm (6 to 8 in) were sliced off the inner faces of many, to facilitate their fixing.[43] (Stones left behind were sold in an online auction when the quarry was abandoned and flooded in 2003.[44]) 10,000 tons of granite blocks were shipped via the Panama Canal to California, then trucked from Long Beach to Arizona. They were used to face a new, purpose-built hollow core steel-reinforced concrete structure, ensuring the bridge would support the weight of modern traffic.[45] The bridge was reconstructed by Sundt Construction at Lake Havasu City, Arizona, and was re-dedicated on 10 October 1971 in a ceremony attended by London's Lord Mayor and celebrities. The bridge carries the McCulloch Boulevard and spans the Bridgewater Channel, an artificial, navigable waterway that leads from the Uptown area of Lake Havasu City.[46]

Modern London Bridge (1973–present)

The current London Bridge was designed by architect Lord Holford and engineers Mott, Hay and Anderson.[47] It was constructed by contractors John Mowlem and Co from 1967 to 1972,[47][48] and opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 16 March 1973.[49][50][51] It comprises three spans of prestressed-concrete box girders, a total of 833 feet (254 m) long. The cost of £4 million (£60.1 million in 2021),[39] was met entirely by the Bridge House Estates charity. The current bridge was built in the same location as Rennie's bridge, with the previous bridge remaining in use while the first two girders were constructed upstream and downstream. Traffic was then transferred onto the two new girders, and the previous bridge demolished to allow the final two central girders to be added.[52]

In 1984, the British warship HMS Jupiter collided with London Bridge, causing significant damage to both the ship and the bridge.[53]

On Remembrance Day 2004, several bridges in London were furnished with red lighting as part of a night-time flight along the river by wartime aircraft. London Bridge was the one bridge not subsequently stripped of the illuminations, which are regularly switched on at night.

The current London Bridge is often shown in films, news and documentaries showing the throng of commuters journeying to work into the City from London Bridge Station (south to north). An example of this is actor Hugh Grant crossing the bridge north to south during the morning rush hour, in the 2002 film About a Boy.

On 11 July 2009, as part of the annual Lord Mayor's charity appeal and to mark the 800th anniversary of Old London Bridge's completion in the reign of King John, the Lord Mayor and Freemen of the City drove a flock of sheep across the bridge, supposedly by ancient right.[54]

In a terrorist attack on 3 June 2017, three pedestrians on the bridge were driven into with a van and killed. Altogether, eight people died and 48 were injured in the attack. Security barriers were installed on the bridge to help isolate the pedestrian pavement from the road.[55]

Transport

The nearest London Underground stations are Monument, at the northern end of the bridge, and London Bridge at the southern end. London Bridge station is also served by National Rail.

In literature and popular culture

- The nursery rhyme and folk song "London Bridge Is Falling Down" has been speculatively connected to several of the bridge's historic collapses.

- Rennie's New London Bridge is a prominent landmark in T. S. Eliot's poem The Waste Land, wherein he compares the shuffling commuters across London Bridge to the hell-bound souls of Dante's Inferno. Also in that poem is a reference to the "inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold" of the church of St Magnus-the-Martyr, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, which marks the northern approach to the bridge, and the poem also ends with the lines "I sat upon the shore/fishing, with the arid plain behind me./Shall I at least set my lands in order?/London bridge is falling down, falling down, falling down".

- In Charles Dickens' Sketches by Boz, in the story entitled Scotland-yard there is much discussion by coal-heavers on the replacement of London Bridge in 1832, including a portent that the event will dry up the Thames.

- Gary P. Nunn's song "London Homesick Blues" includes the lyrics, "Even London Bridge has fallen down, and moved to Arizona, now I know why."[56]

- English composer Eric Coates wrote a march about London Bridge in 1934.

- London Bridge is named in the World War II song "The King is Still in London" by Roma Campbell-Hunter & Hugh Charles.[57]

- Fergie released a song titled "London Bridge" in 2006 as the lead single of her first solo album, The Dutchess.[58] The music video for the track features the singer on a boat near London's Tower Bridge,[59] which is not London Bridge, but this error didn't stop the song from reaching number one on Billboard's Hot 100.[60]

See also

Notes

- "Statutory Instrument 2000 No. 1117 – The GLA Roads Designation Order 2000". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "About us". TeamLondonBridge. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- Merrifield, Ralph, London, City of the Romans, University of California Press, 1983, pp. 1–4. The terraces were formed by glacial sediment towards the end of the last Ice Age.

- D. Riley, in Burland, J.B., Standing, J.R., Jardine, F.M., Building Response to Tunnelling: Case Studies from Construction of the Jubilee line Extension, London, Volume 1, Thomas Telford, 2001, pp. 103 – 104.

- The site of the new bridge determined the location of London itself. The alignment of Watling Street with the ford at Westminster (crossed via Thorney Island) is the basis for a mooted earlier Roman "London", sited in the vicinity of Park Lane. See Margary, Ivan D., Roman Roads in Britain, Vol. 1, South of the Foss Way – Bristol Channel, Phoenix House Lts, London, 1955, pp. 46 – 47.

- "Engineering Timelines - Roman Bridge, London, site of". engineering-timelines.com. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- Margary, Ivan D., Roman Roads in Britain, Vol. 1, South of the Foss Way – Bristol Channel, Phoenix House Lts, London, 1955, pp. 46–48.

- Jones, B., and Mattingly, D., An Atlas of Roman Britain, Blackwell, 1990, pp. 168–172.

- Merrifield, Ralph, London, City of the Romans, University of California Press, 1983, p. 31.

- Jeremy Haslam, 'The Development of London by King Alfred: A Reassessment'; Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 61 (2010), 109–44. Retrieved 2 August 2014

- Snorri Sturluson (c. 1230), Heimskringla. There is no reference to this event in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. See: Hagland, Jan Ragnar; Watson, Bruce (Spring 2005). "Fact or folklore: the Viking attack on London Bridge" (PDF). London Archaeologist. 12: 328–33.

- See Battle of Brentford (1016)

- Thornbury, Walter, Old and New London, 1872, vol.2, p.10

- Gerhold. London Bridge and its Houses. pp. 4, 11–12, 16.

- Pierce, p.45 and Jackson, p.77

- Rev. John Ray, "Book of Proverbs", 1670, cited in Jackson, p.77

- Gerhold. London Bridge and its Houses. pp. 13, 19–21, 36, 45–46.

- Gerhold. London Bridge and its Houses. pp. 60–75.

- Gerhold. London Bridge and its Houses. pp. 26–32.

- Dunton, Larkin (1896). The World and Its People. Silver, Burdett. p. 23.

- "Vision of Britain – Paul Hentzner – Arrival and London". www.visionofbritain.org.uk.

- Home (1932). "Old London Bridge". Nature. 129 (3244): 232. Bibcode:1932Natur.129S..16.. doi:10.1038/129016c0. S2CID 4112097.

- Timbs, John. Curiosities of London. p.705, 1885. Available: books.google.com. Accessed: 29 September 2013

- Gerhold, London Bridge and its Houses, pp. 32-3; Sabine, Ernest L., "Latrines and Cesspools of Mediaeval London," Speculum, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Jul. 1934), pp. 305–306, 315. Earliest evidence for the multi-seated public latrine is from a court case of 1306.

- Jackson. London Bridge. pp. 30–31.

- Gerhold. London Bridge and its Houses. pp. 57, 82–90.

- Ways of the World: A History of the World's Roads and of the Vehicles That Used Them, M. G. Lay & James E. Vance, Rutgers University Press 1992, p. 199.

- Gerhold. London Bridge and its Houses. p. 93.

- Pierce 2001, pp. 235–236

- Pierce 2001, p. 252

- Pierce 2001, p. 252–256

- Gerhold, London Bridge and its Houses, pp. 100–101.

- Pierce 2001, p. 260

- Pierce 2001, pp. 261–263

- Pierce 2001, p. 278–279

- "Article on Iron Bridges". Encyclopedia Britannica. 1857.

- Smiles, Samuel (October 2001). The Life of Thomas Telford. ISBN 1404314857.

- A fragment from the old bridge is set into the tower arch inside St Katharine's Church, Merstham.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- A dozen granite corbels prepared for this widening went unused, and still lie near Swelltor Quarry on the disused railway track a couple of miles south of Princetown on Dartmoor.

- "How London Bridge was sold to the States". Watford Observer. 27 March 2002. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- "How London Bridge was sold to the States (From This Is Local London)". 16 January 2012. Archived from the original on 16 January 2012.

- "London Bridge is still here! – 21/12/1995 – Contract Journal". Archived from the original on 6 May 2008.

- "Merrivale Quarry, Whitchurch, Tavistock District, Devon, England, UK". www.mindat.org.

- Elborough, Travis (2013). London Bridge in America: The tall story of a transatlantic crossing. Random House. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-1448181674. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- Wildfang, Frederic B. (2005). Lake Havasu City. Chicago, IL: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 105–122. ISBN 978-0738530123. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- "Carillion accepts award for London Bridge project". Building talk. 14 November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- "Where Thames Smooth Waters Glide". Archived from the original on 12 April 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- "London's new bridge— Open today: the latest in a line that goes back 1000 years", Evening Standard (London), March 16, 1973, p. 27

- "Rooftop vigil as the Queen opens bridge", Leicester Mercury, 16 March 1973, p. 1

- "Queen Hails New London Bridge", by Tom Lambert, Los Angeles Times, March 17, 1973, p. I-3 (Queen Elizabeth opened the newest London Bridge Friday, saying it showed no signs of falling down.")

- Yee, plate 65 and others

- Morris, Rupert (14 June 1984). "Frigate hits London Bridge". The Times. No. 61857. London. col E-G, p. 1.

- "The Lord Mayor's Appeal | A Better City for All | The Lord Mayor's Appeal 2019/2020". www.thelordmayorsappeal.org.

- "'Van hits pedestrians' on London Bridge in 'major incident'". BBC. 3 June 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- "London Homesick Blues". International Lyrics Playground. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- Huntley, Bill. "The King is Still in London". International Lyrics Playground. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Vineyard, Jennifer. "Black Eyed Peas' Fergie Gets Rough And Regal In First Video From Solo LP". MTV News. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Fergie - London Bridge (Oh Snap) (Official Music Video), retrieved 9 August 2021

- "Fergie". Billboard. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

References

- Gerhold, Dorian, London Bridge and its Houses, c.1209-1761, London Topographical Society, 2019, ISBN 978-17-89257-51-9; 2nd edition, Oxbow Books, 2021, ISBN 1-789257-51-4.

- Home, Gordon, Old London Bridge, John Lane the Bodley Head Limited, 1931.

- Jackson, Peter, London Bridge – A Visual History, Historical Publications, revised edition, 2002, ISBN 0-948667-82-6.

- Murray, Peter & Stevens, Mary Anne, Living Bridges – The inhabited bridge, past, present and future, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1996, ISBN 3-7913-1734-2.

- Pierce, Patricia, Old London Bridge – The Story of the Longest Inhabited Bridge in Europe, Headline Books, 2001, ISBN 0-7472-3493-0.

- Watson, Bruce, Brigham, Trevor and Dyson, Tony, London Bridge: 2000 years of a river crossing, Museum of London Archaeology Service, ISBN 1-901992-18-7.

- Yee, Albert, London Bridge – Progress Drawings, no publisher, 1974, ISBN 978-0-904742-04-6.

External links

- The London Bridge Museum and Educational Trust

- Views of Old London Bridge ca. 1440, BBC London

- Southwark Council page with more info about the bridge

- Virtual reality tour of Old London Bridge

- Old London Bridge, Mechanics Magazine No. 318, September 1829

- The London Bridge Experience

- The bridge that crossed an ocean (And the man who moved it) BBC News, 23 September 2018