Battle of Cable Street

The Battle of Cable Street was a series of clashes that took place at several locations in the inner East End of London, most notably Cable Street, on Sunday 4 October 1936. It was a clash between the Metropolitan Police, sent to protect a march by members of the British Union of Fascists[1] led by Oswald Mosley, and various de jure and de facto anti-fascist demonstrators, including local trade unionists, communists, anarchists, British Jews, supported in particular by Irish workers,[2] and socialist groups.[3][4][5] The anti-fascist counter-demonstration included both organised and unaffiliated participants.

| Battle of Cable Street | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

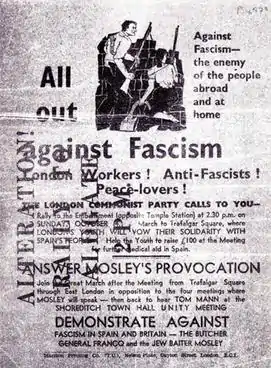

Flyer distributed by the London Communist Party | ||||

| Date | 4 October 1936 | |||

| Location | 51.5109°N 0.0521°W | |||

| Caused by | Opposition to a fascist march through East London | |||

| Methods | Protest | |||

| Parties | ||||

| Lead figures | ||||

| Number | ||||

| ||||

| Casualties | ||||

| Injuries | ~175 | |||

| Arrested | ~150 | |||

Background

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) had advertised a march to take place on Sunday 4 October 1936, the fourth anniversary of their organisation. Thousands of BUF followers, dressed in their Blackshirt uniform, intended to march through the heart of the East End, an area which then had a large Jewish population.[6]

The BUF would march from Tower Hill and divide into four columns, each heading for one of four open air public meetings where Mosley and others would address gatherings of BUF supporters:[7][8]

- Salmon Lane, Limehouse at 5pm

- Stafford Road, Bow at 6pm

- Victoria Park Square, Bethnal Green at 6pm

- Aske Street, Shoreditch at 6:30pm

The Jewish People's Council organised a petition, calling for the march to be banned, which gathered the signature of 100,000 East Londoners, including the Mayors of the five East London Boroughs (Hackney, Shoreditch, Stepney, Bethnal Green and Poplar)[9][10] in two days.[11] Home Secretary John Simon denied the request to outlaw the march.[12]

Numbers involved

Very large numbers of people took part in the events, in part due to the good weather, but estimates of the numbers of participants vary enormously:

- Estimates of Fascist participants range from 2,000–3,000[13] up to 5,000.[8]

- There were 6,000–7,000 policemen, including many mounted police.[13] The Police had wireless vans[8] and a spotter plane[8] sending updates on crowd numbers and movements to Sir Philip Game's HQ, established on a side street by Tower Hill.[8]

- Estimates of the number of anti-fascist counter-demonstrators range from 100,000[14][8] to 250,000,[15] 300,000,[16] 310,000[17] or more.[18]

Events

Tower Hill

The fascists began to gather at Tower Hill from approximately 2:00 p.m., there were clashes between fascists and anti-fascists at Tower Hill and Mansell Street as they did so, while the anti-fascists also temporarily occupied the Minories. The BUF set up a casualty dressing station in the Tower Hill area, as did their Independent Labour Party and Communist opponents who each had a dressing station.[8]

Aldgate and its approaches

The largest confrontation took place around Aldgate, where the conflict was between those seeking to block the BUF march, and the Metropolitan Police who were trying to clear a route for the march to proceed along. The streets around Aldgate were broad, and impossible to effectively barricade, except by blocking it with large crowds of determined people. These efforts were helped when a number of tram cars were abandoned in the road by their drivers, possibly deliberately.[19]

There were dense crowds along the A11 (the length of Aldgate High Street, Whitechapel High Street and some way along Whitechapel Road) and its side streets, with the greatest concentration of people at Gardiner's Corner; the junction of Whitechapel High Street with Leman Street (leading from Tower Hill), Commercial Street and Commercial Road (the junction of Commercial Road and Whitechapel High Street has since moved east by 100 metres).[20][21]

Cable Street

Protesters built a number of barricades on narrow Cable Street and its side streets. The main barricade was by the junction with Christian Street, about 300 metres along Cable Street in the St George in the East area of Wapping. Just west of the main barricade, another barricade was erected on Back Church Lane; the barrier was erected under the railway bridge, just north of the junction with Cable Street.[22]

The Police attempts to take and remove the barricades were resisted in hand-to-hand fighting and also by missiles, including rubbish, rotten vegetables and the contents of chamber pots thrown at the police by women in houses along the street.[23]

Decision at Tower Hill

Mosley arrived in an open topped black sports car, escorted by Blackshirt motorcyclists, just before 3:30.[24] By this time, his force had formed up in Royal Mint Street and neighbouring streets into a column nearly half a mile long, and was ready to proceed.[24]

However, the police, fearing more severe disorder if the march and meetings went ahead, instructed Mosley to leave the East End, though the BUF were permitted to march in the West End instead.[11] The BUF event finished in Hyde Park.[25]

Aftermath

The anti-fascists were delighted by their success in preventing the march, and by the unity of the community response, in which very large numbers of East-Enders of all backgrounds resisted Mosley. The event is frequently cited by modern Antifa movements as "...the moment at which British fascism was decisively defeated".[28][4] The Fascists presented themselves as the law-abiding party who were denied free speech by a weak government and police force in the face of mob violence. After the event the BUF experienced an increase in membership, although their activity in Britain was severely limited.[29][30]

Following the battle, the Public Order Act 1936 outlawed the wearing of political uniforms and forced organisers of large meetings and demonstrations to obtain police permission. Many of the arrested demonstrators reported harsh treatment at the hands of the police.[31]

Notable participants

British Union of Fascists

Metropolitan Police

Counter-demonstrators

Many leading British communists were present at the Battle of Cable Street, some of whom partially credited the battle for shaping their political beliefs. Some examples include:

- Bill Alexander; communist and the commander of the International Brigade's British Battalion.[32]

- Fenner Brockway, Secretary of the Independent Labour Party.[24]

- Jack Comer, a gangster of Jewish heritage.[33]

- Father John Groser, Anglican priest and prominent Christian socialist.[34]

- Gladys Keable; communist and the future children's editor of the Morning Star.[32]

- Bill Keable; communist and the husband of Gladys Keable, who would become the Morning Star's director.[32]

- Max Levitas, a Jewish Communist activist described by the Morning Star as the "last survivor of the Battle of Cable Street".[35]

- Betty Papworth, communist organizer and wife of Bert Papworth.[36]

- Phil Piratin, member of the Communist Party of Great Britain.[37]

- Alan Winnington; communist, journalist and war correspondent.[32]

- Charlie Hutchinson, communist and only Black-British member of the International Brigades[38]

Commemoration

Between 1979 and 1983, a large mural depicting the battle was painted on the side of St George's Town Hall. It stands in Cable Street, about 350 metres east of the main barricade that stood by the junction with Christian Street. A red plaque in Dock Street (just south of the Royal Mint Street, Leman Street, Cable Street, Dock Street junction) also commemorates the incident.[39]

Numerous events were planned in East London for the battle's 75th anniversary in October 2011, including music[40] and a march,[41] and the mural was once again restored. In 2016, to mark the battle's 80th anniversary, a march took place from Altab Ali Park to Cable Street.[42] The march was attended by some of those who were originally involved.[43]

In popular culture

- The Arnold Wesker play Chicken Soup with Barley depicts an East End Jewish family on the day of the Battle of Cable Street.[44]

- British folk punk band The Men They Couldn't Hang relate the battle in their 1986 song "Ghosts of Cable Street".[45]

- The 2010 BBC revival of the Upstairs Downstairs series devotes an episode to the Battle of Cable Street.[46]

- The incident is depicted in the 2012 novel Winter of the World by Welsh-born author Ken Follett.[47]

- The song "Cable Street" by English folk trio The Young'uns tells the story of the confrontation from the perspective of a young anti-fascist fighter.[48]

- The song "Cable Street Again" by the Scottish black metal band Ashenspire references the Battle of Cable Street in its title and lyrics.[49]

- The book Night Watch by Terry Pratchett features a Battle of Cable Street.[50]

- In the 15 February 2019 episode of EastEnders, Dr Harold Legg and Dot Branning watch a documentary about the battle on DVD and Dr Legg recounts the events of the battle to Dot before dying. He explains that it was at the Battle of Cable Street that he met his wife Judith.[51]

- The Scottish anarcho-punk band Oi Polloi refers the event in several of their songs, most prominently in "Let The Boots Do The Talking".[52]

- The Royal Shakespeare Company 2023 production of the Merchant of Venice is set during the Cable Street battle.[53]

See also

- Battle of George Square – a riot in Glasgow in 1919 in which William Gallacher (a colleague of Phil Piratin) was involved

- Battle of Carfax – skirmish in Oxford between the BUF and anti-fascists of the Labour Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain.

- Battle of Stockton – an earlier incident between BUF members and anti-fascists in Stockton-on-Tees on 10 September 1933

- Battle of South Street – an incident between BUF members and anti-fascists in Worthing on 9 October 1934

- Battle of De Winton Field – a clash between BUF members and anti-fascists in the Rhondda on 11 June 1936

- Battle of Holbeck Moor – a clash between BUF members and anti-fascists in Leeds on 27 September 1936

- Battle of Stepney – a gunfight that took place in 1911, a few streets away

- Christie Pits riot – a similar incident that took place in Toronto on 16 August 1933

- 6 February 1934 crisis – a similar event that took place in Paris

- Battle of Praça da Sé – a similar event that took place in São Paulo in 1934

- National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie – a court case arising from a similar situation, a planned fascist march and the response to it

References

- "Cable Street: 'Solidarity stopped Mosley's fascists'". BBC News. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Julia Bard (13 September 2022). "Redefining Antisemitism to Protect Israel From Scrutiny Won't Make Jews Safer". Jacobin. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- Barling, Kurt (4 October 2011). "Why remember Battle of Cable Street?". BBC News. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Philpot, Robert. "The true history behind London's much-lauded anti-fascist Battle of Cable Street". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "The Battle of Cable Street". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- hate, HOPE not. "The Battle of Cable Street". www.cablestreet.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Cable Street". History Workshop. 8 January 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

Website shows the original BUF leaflet including exact locations and times

- Lewis, Jon E. (2008). London, The Autobiography. Constable. p. 401. ISBN 978-1-84529-875-3. Lewis uses the East London Advertiser as primary source, and also provides editorial commentary. This source only gives the districts where the meetings would take place, not times or the exact locations.

- "Sir Oswald Mosley". Jewish Chronicle. 9 October 1936.

- "ILP souvenir leaflet". Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- Sir Philip Game. "'No pasarán': the Battle of Cable Street". National Archives. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- Piratin, Phil (2006). Our Flag Stays Red. Lawrence & Wishart. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-905007-28-8. cited by Olivia, Lottie Smith (July 2021). Exploring Anti-Fascism in Britain Through Autobiography from 1930 to 1936 (PDF) (MRes). Bournemouth University. p. 72.

- Jones, Nigel, Mosley, Haus, 2004, p. 114

- Marr, Andrew (2009). The Making of Modern Britain. Macmillan. pp. 317–318. ISBN 978-0-230-70942-3.

- "The official interpretation board at the Cable Street mural". Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- "Independent Labour Party leaflet". Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- "Daily Chronicle, cited in a TUC Book on Cable Street" (PDF). pp. 11–12. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- "TUC Book on Cable Street" (PDF). pp. 11–12. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

It makes reference to contemporary estimates as high as half a million, but does not give a primary source.

- "Fascists and police routed: the battle of Cable Street - Reg Weston". Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- Miller, Andrew (2007). The Earl of Petticoat Lane. Arrow. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-900913-99-0.

- Ramsey, Winston (1997). The East End. Then and Now. Battle of Britain Prints Limited. p. 384-389. ISBN 978-0-09-947873-7.

- "Recollections and sketches of James Boswell". Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- "Torah For Today: The Battle of Cable Street". Jewish News. 30 April 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- "Fascist march stopped after disorderly scenes". Guardian newspaper. 5 October 1936. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- "Eight decades after the Battle of Cable Street, east London is still united". The Guardian. 16 April 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Brooke, Mike (30 December 2014). "Historian Bill Fishman, witness to 1936 Battle of Cable Street, dies at 93". News. London. Hackney Gazette. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Levine, Joshua (2017). Dunkirk : the history behind the major motion picture. London. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-00-825893-1. OCLC 964378409.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Penny, Daniel (22 August 2017). "An Intimate History of Antifa". The New Yorker. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Webber, G.C. (1984). "Patterns of Membership and Support for the British Union of Fascists". Journal of Contemporary History. Sage Publications Inc. 19 (4): 575–606. doi:10.1177/002200948401900401. JSTOR 260327. S2CID 159618633. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- Philpot, Robert. "The true history behind London's much-lauded anti-fascist Battle of Cable Street". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Kushner, Anthony and Valman, Nadia (2000) Remembering Cable Street: fascism and anti-fascism in British society. Vallentine Mitchell, p. 182. ISBN 0-85303-361-7

- Meddick, Simon; Payne, Simon; Katz, Phil (2020). Red Lives: Communists and the Struggle for Socialism. UK: Manifesto Press Cooperative Limited. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-907464-45-4.

- "Jack Spot : the 'Einstein of crime'". The Jewish Chronicle. 20 April 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- "St John Beverley Groser (1890-1966) and Michael Groser (1918-2009)". St George in the East. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- Davis, Mary (16 November 2018). "Remembering Max Levitas – Jewish Communist and last survivor of the Battle of Cable Street". The Morning Star. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- Carrier, Dan (15 August 2008). "Betty Papworth". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- "Obituary: Phil Piratin". The Independent. 18 December 1995. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- Meddick, Simon; Katz, Phil; Payne, Liz (2020). Red Lives: Communists and the Struggle for Socialism. UK: Manifesto Press Cooperative Limited. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-907464-45-4.

- "Battle of Cable Street - Dock Street". London Remembers. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Phil Katz. "Communist Party – Communist Party". Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Cable Street 75. "Cable Street 75". Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Brooke, Mike. "'They Shall Not Pass' message from the past for Battle of Cable Street 80th anniversary". East London Advertiser. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- Rod McPhee (1 October 2016). "'We still haven't learned the lesson of the Battle of Cable Street 80 years on'". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Chicken Soup with Barley, Royal Court, London". The Independent. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- "Ghosts of Cable Street". Song Lyrics. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- "Upstairs Downstairs – episode synopses". BBC. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- Follett, Ken (2012). Winter of the World. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-5098-4852-2.

- "Cable Street" – via www.youtube.com.

- "Cable Street Again, by Ashenspire". Ashenspire. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- "Mark Reads 'Night Watch': Part 15". Mark Reads. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- Sugarman, Daniel (18 February 2019). "Jewish character dies on EastEnders". Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- "Let the Boots do the Talking". Genius. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- "The Merchant of Venice". Retrieved 7 October 2023.

External links

- The Battle of Cable Street 80th anniversary

- News footage from the day News reel from youtube.com

- Video for the Ghosts of Cable Street by 'They Men They Couldn't Hang' set to images of the battle

- Historical article by David Rosenberg linked to the 'battle's 75th anniversary

- The Battle of Cable Street as told by the Communist Party of Britain.

- "Fascists and Police Routed at Cable Street" a personal account of the battle by a participant.

- Cable Street and the Battle of Cable Street.

- Google Earth view of the junction of Cable Street and Christian Street as it is now

- The Myth of Cable Street on the History Today website

- A police constable's account – Tom Wilson was on duty at Cable Street