Sacré-Cœur, Paris

The Basilica of Sacré Coeur de Montmartre (Sacred Heart of Montmartre), commonly known as Sacré-Cœur Basilica and often simply Sacré-Cœur (French: Sacré-Cœur de Montmartre, pronounced [sakʁe kœʁ]), is a Roman Catholic church and minor basilica in Paris dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. It was formally approved as a national historic monument by the National Commission of Patrimony and Architecture on December 8, 2022.[1]

| Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Montmartre | |

|---|---|

Basilique du Sacré-Cœur de Montmartre | |

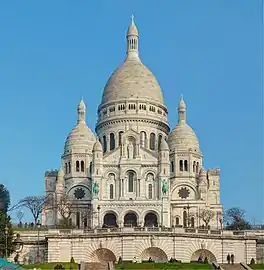

The Basilica of Sacré-Cœur de Montmartre, as seen from the base of the butte Montmartre | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Province | Archdiocese of Paris |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Minor basilica |

| Year consecrated | 1919 |

| Location | |

| Location | Paris, France |

| Geographic coordinates | 48°53′12″N 2°20′35″E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Paul Abadie |

| Groundbreaking | 1875 |

| Completed | 1914 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 85 metres (279 ft) |

| Width | 35 metres (115 ft) |

| Height (max) | 83 metres (272 ft) |

| Materials | Travertine stone |

| Website | |

| sacre-coeur-montmartre | |

Sacré-Cœur Basilica is located at the summit of the butte of Montmartre. From its dome two hundred meters above the Seine, the basilica overlooks the entire city of Paris and its suburbs. It is the second most popular tourist destination in the capital after the Eiffel Tower.[1]

The basilica was first proposed by Felix Fournier, the Bishop of Nantes, in 1870 after the defeat of France and the capture of Napoleon III at the Battle of Sedan in the Franco-Prussian War. He attributed the defeat of France to the moral decline of the country since the French Revolution, and proposed a new Parisian church dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.[2]

The basilica was designed by Paul Abadie, whose Neo-Byzantine-Romanesque plan was selected from among seventy-seven proposals. Construction began in 1875 and continued for forty years under five different architects. Completed in 1914, the basilica was formally consecrated in 1919 after World War I.[3]

Sacré-Cœur Basilica has maintained a perpetual adoration of the Holy Eucharist since 1885. The site is traditionally associated with the martrydom of Saint Denis, the patron saint of Paris.[4]

History

Proposal

The plan to build a new Parisian church dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus was first proposed on September 4, 1870, by Felix Fournier, the Bishop of Nantes, following the defeat of France and the capture of Emperor Napoleon III by the Prussians at the Battle of Sedan in the Franco-Prussian War. Until his death in 1877, Fournier was an active builder who completed the long-delayed restoration of Nantes Cathedral. He wrote that the defeat of France in 1870 was a divine punishment for the moral decline of the country since the French Revolution.[4]

In January 1871, Bishop Fournier was joined by the philanthropist Alexandre Legentil, who was a follower of Frederic Ozanam, the founder of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul. Legentil declared that France had been justly punished for its sins by the defeat of the French Army at Sedan and the imprisonment of the Pope in Italy by Italian nationalists. He wrote, "We recognize that we were guilty and justly punished. To make honourable amends for our sins, and to obtain the infinite mercy of the Sacred Heart of our Lord Jesus Christ and the pardon of our sins, as well as extraordinary aid which alone can delivery our sovereign Pontiff from captivity and reverse the misfortune of France, we promise to contribute to the erection in Paris of a sanctuary dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus." The influence of Legentil led to a successful fundraising campaign based entirely on private contributions.[4]

Site

Montmartre was selected as the site of the new basilica due to its prominent height and visibility from many parts of the city. Since the location included land belonging to the local government as well as private owners, the French parliament assisted in securing the site by declaring that the construction of the basilica was in the national interest.[5] In July 1873, the proposal was finally brought forward and approved in the National Assembly with the official statement that "it was necessary to efface by this work of expiation the crimes which have crowned our sorrows."[6] The groundbreaking for the new church finally took place in 1875.

Apart from its physical attributes, Montmartre or the "Hill of the Martyrs" was also chosen for its association with the early Christian church. According to tradition, it was the place where the patron saint of Paris, Saint Denis of Paris, was beheaded by the Romans. His tomb became the site of the Basilica of Saint Denis, the traditional resting place for the kings of France until the French Revolution.

In addition, Montmartre was the birthplace of the Society of Jesus, one of the largest and most influential religious orders in the history of the Catholic Church. In 1534, Ignatius of Loyola and a few of his followers made their vows in Saint-Pierre de Montmartre, one of the oldest churches in Paris.[7] The church survived the Revolution although the Montmartre Abbey to which it belonged was destroyed.[8]

Construction

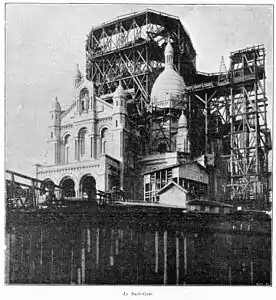

Construction of Sacré-Cœur underway (1882)

Construction of Sacré-Cœur underway (1882) Construction of Sacré-Cœur (1897)

Construction of Sacré-Cœur (1897) The funicular railway to Sacré-Cœur (about 1905)

The funicular railway to Sacré-Cœur (about 1905)

A competition was held for the design of the basilica and attracted seventy-seven proposals. Architect Paul Abadie was selected,[3] and the cornerstone finally laid on June 16, 1875.[9]

The early construction was delayed and complicated by unstable foundations. Eighty-three wells, each thirty meters deep, had to be dug under the site and filled with rock and concrete to serve as subterranean pillars supporting the basilica.[10] Construction costs, estimated at 7 million francs drawn entirely from private donors, were expended before any above-ground structure became visible. A provisional chapel was consecrated on March 3, 1876, and pilgrimage quickly brought in additional funding.[11]

Not long after the foundation was completed in 1884, Abadie died and was succeeded by five other architects who made extensive modifications: Honoré Daumet (1884–1886), Jean-Charles Laisné (1886–1891), Henri-Pierre-Marie Rauline (1891–1904), Lucien Magne (1904–1916), and Jean-Louis Hulot (1916–1924).

During construction, opponents of the basilica were relentless in their effort to hinder its progress. In 1882, the walls of the church were barely above its foundations when the left-wing coalition led by Georges Clemenceau won the parliamentary election. Clemenceau immediately proposed halting the work, and the parliament blocked all further funding for the project. However, faced with enormous liabilities of twelve million francs from project cancellation, the government had to allow the construction to proceed.[9]

In 1891, the interior of the basilica was completed, dedicated and opened for public worship. Still, in 1897, Clemenceau made another attempt to block its completion in the parliament, but his motion was overwhelmingly defeated since the cancellation of the project would require repaying thirty million francs to eight million people who had contributed to its construction.[9]

The dome of the church was completed in 1899, and the bell tower finished in 1912. The basilica was completed in 1914 and formally dedicated in 1919 after World War I.

Controversy over the church

Criticism of the church by leftist journalists and politicians for its alleged connection with the destruction of the Paris Commune continued from the late 19th century into the 20th and 21st centuries, even though the church had been proposed before the Paris Commune took place. In 1898, Emile Zola wrote sarcastically, "France is guilty. It must do penitence. Penitence for what? For the Revolution, for a century of free speech and science, and emancipated reason... for that they built this gigantic landmark that Paris can see from all of its streets, and cannot be seen without feeling misunderstood and injured."[12]

Shortly after the completed Statue of Liberty was transported from France to the United States, opponents of Sacré-Cœur came up with a new strategy. They proposed installing a full-size copy of the Statue of Liberty on top of Montmartre, directly in front of the basilica, which would entirely block the view of the church. This idea was eventually dropped as expensive and impractical.[13]

A bomb was exploded inside the church in 1976.[14]

To make their feelings about the church clear, the socialist mayor of Paris Bertrand Delanoë and the mayor of the 18th arrondissement Daniel Vaillant, also member of the Socialist Party, renamed the square in front of and below the church in 2004 in honor of Louise Michel, the prominent anarchist and participant in the Paris Commune.

Lionel Jospin, socialist Prime Minister between 1997 and 2002 also expressed his wish that the basilica be demolished as a symbol of "obscurantism, bad taste and reactionism."[15][16]

In 2021, to avoid celebrating the church's history in the same year as the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune, leftist members of the French parliament blocked a measure to declare the church a national historic monument and postponed it until 2022.[17]

The church was finally named as a national historic monument by a unanimous vote of the National Commission of Patrimony and Architecture on December 8, 2022.This decision was immediately attacked by the leftist politician Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who called it "a glorification of the assassination of 32,000 Paris Communards shot in just 8 days."[18].

Description

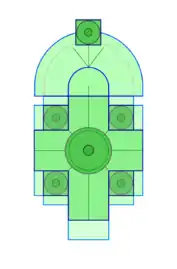

The church is 85 meters long and thirty-five meters wide. It is composed of a large central rotunda, around which are placed a small nave, two transepts, and an advance-choir, which form a cross. The porch of the church has three bays, and is modelled after the porch of Périgueux Cathedral. The dominant feature is the immense elongated ovoid cupola, 83.33 meters high, surrounded by four smaller cupolas. At the north end is the campanile, or bell tower, 84 meters high, containing the "Savoyarde", the largest bell in France.[19]

The overall style of the structure is a free interpretation of Romano-Byzantine architecture. This was an unusual architectural style at the time, and was in part a reaction against the neo-Baroque of the Palais Garnier opera house by Charles Garnier, and other buildings of the Napoleon III style.[20] The construction was eventually handed on to a series of new architects, including Garnier himself, who was a counsellor to the architect Henri-Pierre Rauline between 1891 and 1904,

Some elements of the design, particularly the elongated domes and the structural forms of the windows on the south façade, are Neo-classical, and were added by the later architects Henri-Pierre Rauline and Lucien Magne.[21]

Exterior

Plan of the church, with campanile at north end, and four smaller cupolas around central dome

Plan of the church, with campanile at north end, and four smaller cupolas around central dome Sacré-Cœur seen from above

Sacré-Cœur seen from above South façade, the main entrance overlooking Paris

South façade, the main entrance overlooking Paris Close-up view of Sacre-Coeur Basilica

Close-up view of Sacre-Coeur Basilica

The campanile, or bell tower, on the north front, houses the nineteen-ton Savoyarde bell (one of the world's heaviest), cast in 1895 in Annecy. It alludes to the attachment of Savoy to France in 1860.

Detail of the south façade

Detail of the south façade The north façade, and choir

The north façade, and choir The campanile or bell tower

The campanile or bell tower

The porch of the south façade, the main entrance, is loaded with sculpture combining religious and French national themes. It is topped with a statue representing the Sacred Heart of Christ. The arches of the façade are decorated with two equestrian statues of French national saints Joan of Arc (1927) and King Saint Louis IX, both executed in bronze by Hippolyte Lefèbvre.

Statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, south façade

Statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, south façade Statue of Joan of Arc (south façade)

Statue of Joan of Arc (south façade) Saint Louis (Louis IX) (south façade)

Saint Louis (Louis IX) (south façade)

The white stone of Sacré-Cœur is travertine limestone of a type called Chateau-Landon, quarried in Souppes-sur-Loing, in Seine-et-Marne, France. The particular quality of this stone is that it is extremely hard with a fine grain, and exudes calcite on contact with rainwater, making it exceptionally white.[22]

Interior

The choir and the altar

The choir and the altar Coupola from below. Each sculpted angel carries a symbol of the passion of Christ.

Coupola from below. Each sculpted angel carries a symbol of the passion of Christ. Interior of the North Dome

Interior of the North Dome

The nave is dominated by the very high dome, which symbolises the celestial world, resting upon a rectangular space,symbolising the terrestrial world. The two are joined by massive columns, which represent the passage between the two worlds.[23]

The plan of the interior is a Greek cross, with the altar in the center, modelled after Byzantine churches. More traditional Latin features, the choir and the disambulatory, were added around the altar. The light in interior of the church is unusually dim, due to the height of the windows above the altar, and this contributes to the mystical effect. Other Byzantine features in the interior include the designs of the tile floor and the glasswork.[23]

The Triumph of the Sacred Heart of Jesus mosaic

Detail of Sacré-Cœur's "Christ in Majesty" - left side

Detail of Sacré-Cœur's "Christ in Majesty" - left side "Christ in Majesty" - center

"Christ in Majesty" - center Detail of "Christ in Majesty" - right side

Detail of "Christ in Majesty" - right side

The mosaic over the choir, entitled The Triumph of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, is the largest and most important work of art in the church. It was created by Luc-Olivier Merson, H. M. Magne and R. Martin, and was dedicated in 1923. The mosaic is composed of 25,000 enamelled and gilded pieces of ceramic, and covers 475 square meters, making it one of the largest mosaics in the world.[23]

The central figure is Jesus Christ, dressed in white, with open arms offering his heart, decorated with gold. He is joined by his mother, the Virgin Mary, and by the Archangel Michael, the protector of the church and of France. At his feet, kneeling, is Saint Joan of Arc offering him a crown. A figure of Pope Leo XIII offers a globe to Christ, symbolising the world.[24]

To the right of Christ is a scene titled "The Homage of France to the Sacred Heart;" a group of popes and cardinals present a model of the basilica to Christ. On his left is "The Homage of the Catholic Church to the Sacred Heart": where people in the costumes of the five continents pay their homage to the Sacred Heart. At the base of the mosaic is a Latin inscription, stating that the basilica is a gift from France. "To the Sacred Heart of Jesus, France fervent, penitent and grateful." The word "grateful" was added after World War I.[25]

At the top of the mosaic is another procession, called "the Saints of France and Saints of the Universal Church". In all of the mosaic, the artists adapted elements of Byzantine art in the organization of the figures, the altered perspective, and the use of polychrome colors enhanced with silver and gold.[24]

The basilica complex also includes a garden for meditation, with a fountain. The top of the dome is open to tourists and affords a spectacular panoramic view of the city of Paris, which spreads out to the south of the basilica.

The use of cameras and video recorders is forbidden inside the basilica.

Chapels

_-_2022-04-30_-_65.jpg.webp) Altar of the Chapel of Saint Louis

Altar of the Chapel of Saint Louis Sculpture in inner chapel- Mary with Child

Sculpture in inner chapel- Mary with Child.jpg.webp) The baptismal font

The baptismal font

The interior of the basilica is surrounded by a series of chapels, mostly offered by professional groups or religious orders. The chapels are decreed with sculpture, relief sculpture, and tapestries, often relating to the professions of the donors. For example, the Chapel of the Order of Notre Dame of the Sea is decorated with tapestries illustrating Christ walking on the water and the Miraculous Catch of fish.[23] Beginning to the right of the main entrance, they are:

- The Chapel of the Archangel Michael, or Chapel of the Armies

- The Chapel of Saint Louis (Louis IX) or the Attorneys

- The Tribune of Commerce and Industry (end of the East transept)

- The Chapel of Marguerite-Marie Alacoque

- the Chapel of Notre Dame of the Sea

The apse itself is ringed by an additional seven chapels.

- The Chapel of Saint Francis of Assisi

- The Chapel of Saint John the Baptist, offered by Canada and the Knights of Malta

- The Chapel of Saint Joseph

- The Chapel of the Virgin Mary

- The Chapel of Saint Luke the Evangelist, Comé and Damien, or the Doctors

- The Chapel of Ignace de Loyola

- Th Chapel of Saint Ursula of Cologne

- The Chapel of Saint Vincent de Paul

- The Tribune of Agriculture (at the end of the west transept)

- The chapel of the Queens of France

Crypt

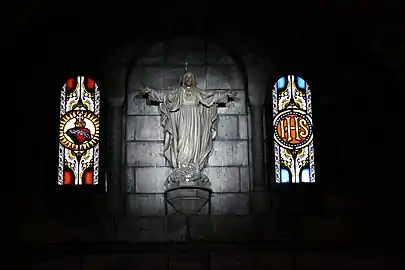

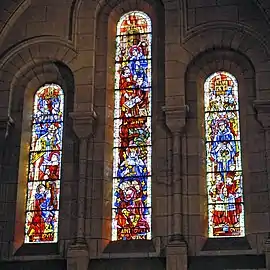

Stained Glass and statue of Christ in the crypt

Stained Glass and statue of Christ in the crypt Display of religious garments in the crypt

Display of religious garments in the crypt Art with candlelight in the crypt

Art with candlelight in the crypt

The crypt below Sacré-Cœur is different from traditional crypts, which are usually underground. At Sacré-Cœur, the crypt has stained glass windows, thanks to a "saut-de-loup", a trench about four meters wide around it, which allows light to enter through windows and oculi of the crypt wall. In the centre of the crypt is the chapel of the Pieta, whose central element is a monument statue of the Virgin Mary at the foot of the cross, at the altar. The statue was made by Jules Coutain in 1895. A series of seven chapels is placed on the east side and seven on the west side of crypt, corresponding to the chapels on the level above. The crypt contains the tombs of important figures in the creation of the basilica, including Cardinals Guibert and Richard.[26]

Art and decoration

Decoration covers the walls, the floor, and the architecture. Much of the decoration is in a distinctly neo-Byzantine style, with intricate patterns, and abundant color.

Stained glass

Windows over the organ

Windows over the organ A rose window depicting the Sacred Heart of Christ

A rose window depicting the Sacred Heart of Christ Window depicting "Christ conquers"

Window depicting "Christ conquers"

Sculpture

.JPG.webp) Saint John Healing the Sick, by Léon Fagel (1851–1913)

Saint John Healing the Sick, by Léon Fagel (1851–1913)_-_2022-04-30_-_11.jpg.webp) Christ with Child (Pieta)

Christ with Child (Pieta) Cardinal Guibert, leading proponent of the basilica, holding its model

Cardinal Guibert, leading proponent of the basilica, holding its model

Saint Hubert by Duchesse d'Uzés (1889)

Saint Hubert by Duchesse d'Uzés (1889) Saints Donatien and Rogatien, by P.Potet (1850) in Crypt

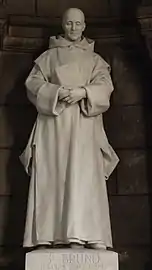

Saints Donatien and Rogatien, by P.Potet (1850) in Crypt Saint Bruno by Henri Louis Noël (1899)

Saint Bruno by Henri Louis Noël (1899)

Grand organ

.jpg.webp) The Grand Organ

The Grand Organ.jpg.webp) The view from behind the organ down to the altar

The view from behind the organ down to the altar

The basilica contains a large and very fine pipe organ built by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, the most celebrated organ builder in Paris in the 19th century. His other organs included those of Saint-Denis Basilica (1841), Sainte-Clotilde Basilica (1859), Saint-Sulpice church and Notre Dame de Paris (1868). The organ is composed of 109 ranks and 78 speaking stops spread across four 61-note manuals and the 32-note pedalboard (unusual before the start of the 20th century; the standard of the day was 56 and 30), and has three expressive divisions (also unusual for the time, even in large organs).[27]

The organ was originally built in 1898 for the Biarritz chateau of the Baron Albert de L'Espée. It was the last instrument built by Cavaillé-Coll. The organ was ahead of its time, containing multiple expressive divisions and giving the performer considerable advantages over other even larger instruments of the day. It was almost identical (tonal characteristics, layout, and casework) to the instrument in Sheffield's Albert Hall, which was destroyed by fire in 1937. However, when installed in Paris in 1905 by Cavaillé-Coll's successor and son-in-law, Charles Mutin, a much plainer case was substituted for the original ornate case.[28]

The organ was recognised as a national landmark in 1981. It has undergone several restorations. The most recent, begun in 1985, replaced only the most severely damaged pneumatic parts, but others have deteriorated and some are no longer usable. The pipes are now covered with a thick layer of dust which impacts the pitch and timbre.[27] Both the organ and the church itself have been recognized as national landmarks.

Bells

The belfry of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Montmartre houses five bells. The four small bells named from largest to smallest are Félicité, Louise, Nicole and Elisabeth, which were the original bells of the church of Saint-Roch and moved to the basilica in 1969.

Below the four bells is a huge bourdon called "The Savoyarde", the biggest bell in France. The full name of the bourdon is “Françoise Marguerite of the Sacred Heart of Jesus". It was cast on May 13, 1891, by the Paccard foundry (Dynasty of Georges, Hippolyte-Francisque and Victor or "G & F") in Annecy-le-Vieux.

The Savoyarde itself only rings for major religious holidays, especially on the occasion of Easter, Pentecost, Ascension, Christmas, Assumption and All Saints. One exception was on the night of August 24, 1944 when La Nueve – 9th Company, Régiment de marche du Tchad of the French 2nd Armored Division – broke into Paris and arrived at the Hôtel de Ville during the Liberation of Paris from Nazi German occupation, becoming the first French Army troops to return to the city since 1940. The bell then rang when Pierre Schaeffer broadcast the news on a Radiodiffusion Nationale broadcast and then, after a playing of "La Marsellaise", asked any priests who were listening to ring their churches' bells.[29] The Savoyarde can be heard from 10 km away.

This bell is the fifth largest in Europe, ranking behind the Petersglocke of Cologne (Germany), the Olympic Bell of London, Maria Dolens of Rovereto (Italy), and the Pummerin of Vienna (Austria). It weighs 18,835 kg, measures 3,03 m of diameter for 9.60 m of outer circumference, with a base thickness of 22 cm and a leaf of 850 kg. With its accessories, its official weight reaches 19,685 kg. It was offered by the four dioceses of Savoy. It was transported to the basilica on October 16, 1895, pulled by a team of 28 horses. In the late 1990s, a crack was noticed in the bell.

Role in Catholicism

The church is dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which was an increasingly popular devotion after the visions of Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque (1647–1690) in Paray-le-Monial.[30]

In response to requests from French bishops, Pope Pius IX promulgated the feast of the Sacred Heart in 1856. The basilica itself was consecrated on 16 October 1919.

Since 1885 (before construction had been completed) the Blessed Sacrament (Christ's body, consecrated during the Mass) has been continually on display in a monstrance above the high altar. Perpetual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament has continued uninterrupted in the basilica since 1885.

Tourists and others are asked to dress appropriately when visiting the basilica and to observe silence as much as possible, so as not to disturb persons who have come from around the world to pray in this place of pilgrimage, especially since the Blessed Sacrament is displayed. Photos are not allowed to be taken in the basilica.

Access

The basilica is accessible by bus or metro line 2 at Anvers station. Sacré-Cœur is open from 06:00 to 22:30 every day. The dome is accessible from 09:00 to 19:00 in the summer and to 18:00 in the winter.[31]

Copy in Martinique

A much smaller version of the basilica, Sacré-Cœur de la Balata, is located north of Fort-de-France, Martinique, on N3, the main inland road. Built for the refugees driven from their homes by the eruption of Mount Pelée, it was dedicated in 1915.[32]

See also

- Architecture of Paris

- List of historic churches in Paris

- Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque, seer and promoter of devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus

- Blessed Mary of the Divine Heart, promoter of the world consecration to the Sacred Heart of Jesus

- Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, a great shrine dedicated to the worship of the Sacred Heart of Jesus

- Sanctuary of Christ the King, the Portuguese national shrine of the Sacred Heart of Jesus

- A statue to François-Jean de la Barre was erected in front of Sacré-Cœur as a counter-action to its construction.

- Valley of the Fallen, Catholic basilica and a monumental memorial in the municipality of San Lorenzo de El Escorial

References

- "Ouest-France", "Le Sacré-Coeur à Paris classé monument historique", October 12, 2022

- "Sacre Coeur". Exploring the Beauty and History of Sacre Coeur.

- The competition was commemorated in Souvenir du Concours de l’Église du Sacré-Cœur (Paris: J. Le Clere) 1874.

- "Le Sacre-Coeur - Monument Historique? Polemique en Vue." by Baudouin Eschapasse, "Le Point" magazine, October 14, 2020

- Harvey it said "Monument and Myth" 1979, pp 380–81 Archived 2020-09-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- Harvey, David, "Memorial and Myth" (1979), p. 369

- "Montmartre, Paris' last village. Facts". Paris Digest. 2018. Archived from the original on 2020-11-07. Retrieved 2018-09-07.

- Rustenholtz, Alain, "Traversées de Paris" (2010), p. 376-387

- Harvey "Monument and Myth" 1979, pp 380–81 Archived 2020-09-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Dictionnaire Historique de Paris" (2013), p. 684

- In 1877, its first full year of operation, over 240,000 francs was collected, and the figure doubled the following year. (Jonas 1993:495).

- Dictionnaire Historique de Paris (2013), p. 684

- Harvey, David, Memorial and Myth (1979), p. 379

- Monument and Myth, 1979, pp 380–81

- « Un square Louise-Michel sur la butte Montmartre » Archived 2019-04-05 at the Wayback Machine, www.leparisien.fr, 28 février 2004 (consulté le 18 octobre 2018).

- « Pourquoi veut-on la peau du Sacré-Cœur ? »

- "Pourquoi veut-on la peau du Sacré-Cœur?" Liberation, February 27, 2017

- Ouest-France, "Le Sacré-Coeur à Paris classé monument historique", December 10, 2022. Recent historians put the number of Communards killed in combat or executed afterwards at between ten to fifteen thousand men, and the basilica was proposed before the Paris Commune took place.(See Paris Commune)

- "Dictionnaire Historique de Paris", p. 684

- Legentil had wanted to demolish Garnier's half-built opera house and build the church on the site of that "scandalous monument of extravagance, indecency and bad taste" (Harvey "Monument and Myth" 1979, P376 Archived 2020-09-24 at the Wayback Machine).

- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; "Églises de Paris" (2010), p. 184

- "architecture". www.sacre-coeur-montmartre.com. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; "Églises de Paris" (2010), p. 184-187

- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; "Églises de Paris" (2010), p. 184-187

- "The Apse Mosaic". www.sacre-coeur-montmartre.com. Archived from the original on 2020-04-06. Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- Jacques Benoist, "Le Sacré-Cœur de Montmartre, Paris", Editions de l'Atelier, 1992, p. 482

- "The Grand Organ". Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- "Basilique Sacré-Coeur". Université du Québec. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009.

- Collins, Larry; Lapierre, Dominique (1991) [1965 Penguin Books]. Is Paris Burning?. Grand Central Publishing. pp. 271–274. ISBN 978-0-446-39225-9. (Available at Internet Archive)

- Raymond Anthony Jonas, France and the cult of the Sacred Heart: an epic tale for modern times, (University of California) 2000, ch. "Building the Church of the National Vow".

- "Opening Hours for the Visit". Basilique du Sacré-Cœur. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- Steve, Bennett. "Sacré-Coeur de la Balata, Martinique: Uncommon Attraction". Uncommon Caribbean. Martinique. Archived from the original on 2021-10-27. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

Bibliography (in French)

- Benoist, Pere Jacques, "Le Sacré-Cœur de Montmartre de 1870 à nos jours ", Les éditions ouvrières (1992), ISBN 978-2-7082-2978-5

- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; Églises de Paris (2010), Éditions Massin, Issy-Les-Moulineaux, ISBN 978-2-7072-0683-1

- "Dictionnaire Historique de Paris", Le livre de Poche, (2013), ISBN 978-2-253-13140-3

- Hillairet, Jacques; Connaissance du Vieux Paris; (2017); Éditions Payot-Rivages, Paris; (in French). ISBN 978-2-2289-1911-1

Further reading

- Jacques Benoist, Le Sacre-Coeur de Montmartre de 1870 a nos Jours (Paris) 1992. A cultural history from the point of view of a former chaplain.

- Yvan Crist, "Sacré-Coeur" in Larousse Dictionnaire de Paris (Paris) 1964.

- David Harvey. Consciousness and the Urban Experience: Studies in the History and Theory of Capitalist Urbanization. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press) 1985.

- Milza, Pierre (2009). L'année terrible: La Commune (mars–juin 1871). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-03073-5.

- David Harvey."The building of the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur", coda to Paris, Capital of Modernity (2003:311ff) Harvey made use of Hubert Rohault de Fleury. Historique de la Basilique du Sacré Coeur (1903–09), the official history of the building of the basilica, in four volumes, printed, but not published.

- Raymond A. Jonas. “Sacred Tourism and Secular Pilgrimage: and the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur”. in Montmartre and the Making of Mass Culture. Gabriel P. Weisberg, editor. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press) 2001.

- Rustenholtz, Alain (2010). Traversées de Paris. Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-684-5.