Basmachi movement

The Basmachi movement (Russian: Басмачество, Basmachestvo, derived from Uzbek: "Basmachi" meaning "bandits")[12] was an uprising against Russian Imperial and Soviet rule in Central Asia by rebel groups inspired by Islamic beliefs.

| Basmachi movement | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War I and the Russian Civil War | |||||||

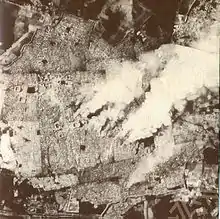

Bukhara under siege by Red Army troops and burning, 1 September 1920 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

(1916–17) (1917) • • (from December 30, 1922) In cooperation with: (1929) (1930) |

Supported by: (until mid-1922)[2]

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

120,000–160,000[4] | Perhaps 30,000 at its height, over 20,000 (late 1919)[5] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

9,338 killed or died of disease 29,617 wounded or sick (Jan. 1921 – July 1922)[6] 516 killed 867 wounded or sick (Oct. 1922 – June 1931)[7] Total: 40,000+ 9,854+ dead 30,484+ wounded or sick | Unknown | ||||||

|

Tens of thousands of civilians killed.[8][9] Several hundred thousand Kazakh and Kyrgyz people killed or evicted with an unknown amount dying to famine according to Sokol.[10] Alternative estimate: 150,000 dead in 1916.[11] | |||||||

| History of Tajikistan |

|---|

| Timeline |

|

|

The movement's roots lay in the anti-conscription violence of 1916 that erupted when the Russian Empire began to draft Muslims for army service in World War I.[13] In the months following the October 1917 Revolution, the Bolsheviks seized power in many parts of the Russian Empire and the Russian Civil War began. Turkestani Muslim political movements attempted to form an autonomous government in the city of Kokand, in the Fergana Valley. The Bolsheviks launched an assault on Kokand in February 1918 and carried out a general massacre of up to 25,000 people.[8][9] The massacre rallied support to the Basmachi who waged a guerrilla and conventional war that seized control of large parts of the Fergana Valley and much of Turkestan. The group's notable leaders were Enver Pasha and, later, Ibrahim Bek.

The fortunes of the movement fluctuated throughout the early 1920s, but by 1923 the Red Army's extensive campaigns had dealt the Basmachis many defeats. After major Red Army campaigns and concessions regarding economic and Islamic practices in the mid-1920s, the military fortunes and popular support of the Basmachi declined.[14] Resistance to Russian rule and Soviet leadership did flare up again, to a lesser extent, in response to collectivization campaigns in the pre-WWII era.[15]

Etymology

The term "Basmachi" is of Uzbek origin and means "Bandit" or "Robber"[16][17] which probably derived from "baskinji" meaning "Attacker".[18] The Russians used the term for the Central Asian resistance fighters, and it was widely used throughout the region to denote them, in an attempt to persuade the public that the fighters were no more than criminals.[16][19]

Background

Prior to World War I, Russian Turkestan was ruled from Tashkent as a Krai or Governor-Generalship. To the east of Tashkent, the Ferghana Valley was an ethnically diverse, densely populated region that was divided between settled farmers (often called Sarts) and nomads (mostly Kyrgyz). Under Russian rule, it was converted into a major cotton-growing region.[20] The resulting economic development brought some small-scale industry to the region, but several scholars suggest that native shop workers were worse off than their Russian counterparts, and the new wealth from cotton was spread unevenly; many farmers became indebted. Many criminals organized into bands, forming the basis for the early Basmachi movement when it began in the Ferghana Valley.[21]

Cotton price-fixing during the First World War made matters worse, and a large, landless rural proletariat soon developed. Muslim clergy decried the gambling and alcoholism that became commonplace, and crime rose considerably.[22]

Major violence in Russian Turkestan broke out in 1916, when the Tsarist government ended its exemption of Muslims from military service. This caused the Central Asian revolt of 1916, centered in modern-day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which was put down by martial law. Tensions between Central Asians (especially Kazakhs) and Russian settlers led to large-scale massacres on both sides. Thousands died, and hundreds of thousands fled, most into the neighbouring Republic of China.[23] The Central Asian revolt of 1916 was the first anti-Russian incident on a mass scale in Central Asia, and it set the stage for native resistance after the fall of Tsar Nicholas II in the following year.[24]

The suppression of the rebellion was a deliberate campaign of annihilation against the Kazakh and Kyrgyz tribes on the part of the Russian soldiers and settlers. Hundreds of thousands of Kazakh and Kyrgyz people were killed or expelled. The ethnic cleansing had its roots in the Tsarist government policy of ethnic homogenization.[25]

Fighting

Kokand autonomy and the start of hostilities

In the aftermath of the February Revolution of 1917, Muslim political forces began to organize. Members of the All-Russian Muslim council formed the Shura-i Islam (Islamic Council), a Jadidist body that sought a federated, democratic state with autonomy for Muslims.[26] More conservative religious scholars formed the Ulema Jemyeti (Board of Learned Men), more concerned with safeguarding Islamic institutions and Sharia law. Together, these Muslim nationalists formed a coalition, but it fell apart after the October Revolution, when the Jadids lent their support to the Bolsheviks who had seized power. The Tashkent Soviet of Soldiers' and Workers' Deputies, an organization dominated by Russian railway workers and colonial proletarians, rejected Muslim participation in government. Stung by this apparent reaffirmation of colonial rule, the Shura-i Islam reunited with Ulema Jemyeti to form the Kokand Autonomous Government. This was to be the nucleus of an autonomous[27] state in Turkestan, governed by Sharia law.[28]

The Tashkent Soviet initially recognized the authority of Kokand, but restricted its jurisdiction to the Muslim old section of Tashkent, and demanded the final say in regional affairs. After violent riots in Tashkent, relations broke down, and despite the leftist leanings of many of its members, Kokand aligned itself with the Whites.[29] Politically and militarily weak, the Muslim government began looking around for protection. To this end, a band of armed robbers led by Irgash Bey were amnestied and recruited to defend Kokand.[27] This force, however, was unable to resist an attack on Kokand by the forces of the Tashkent Soviet. In February, 1918 the Red Army soldiers thoroughly pillaged Kokand, and carried out what was described as a "pogrom,"[30] in which as many as 25,000 people died.[8][9] This massacre, along with the execution of many Ferghana peasants who were suspected of hoarding cotton and food, incensed the Muslim population. Irgash Bey took up arms against the Soviets, declaring himself "Supreme Leader of the Islamic Army", and the Basmachi rebellion started in earnest.[31]

Meanwhile, Soviet troops temporarily deposed Emir Sayeed Alim Khan of Bukhara in favor of the leftist Young Bukharians faction led by Fayzulla Khodzhayev. Russian troops were repulsed by the Bukharan populace after a period of looting, and the Emir retained his throne for the time-being.[32] In the Khanate of Khiva, Basmachi leader Junaid Khan overthrew the Russian puppet and suppressed the modernizing movement of the leftist Young Khivans.[33]

First phase of the revolt in the Ferghana Valley

Irgash Bey's claims to leadership of an army of the faithful won recognition by the clergy of the Ferghana Valley, and he soon controlled a sizable fighting force. Widespread nationalization campaigns carried out from Tashkent had caused economic collapse, and the Ferghana Valley faced famine in absence of grain imports. All these factors drove people to join the Basmachi. The Tashkent Soviet was unable to contain the insurgency, and the end of 1918 decentralized bands of fighters, totaling roughly 20,000, controlled Ferghana and the countryside surrounding Tashkent. Irgash Bey faced rival commanders such as Madamin Bey, who was supported by more moderate Muslim factions, but he secured formal, nominal leadership of the movement at a council in March 1919.[9]

With the Tashkent Soviet in a vulnerable military position, the Bolsheviks left Russian settlers to organize their own defense by creating the Peasant Army of Fergana. This often involved brutal reprisals for Basmachi attacks by Soviet forces and Russian farmers both.[31] The harsh policies of War Communism, however, caused the peasants' army to sour on the Tashkent Soviet. In May 1919, Madamin Bey formed an alliance with the settlers, entailing a non-aggression pact and a coalition army. The new allies made plans for establishing a joint Russian-Muslim state, with power sharing arrangements and cultural rights for both groups.[34][35] Disputes over the Islamic orientation of the Basmachi led to the break-up of the alliance, however, and both Madamin and the settlers suffered defeats at the hands of the Muslim Volga Tatar Red Brigade.[36] The inhabitants of the Ferghana Valley were exhausted after the punishing winter of 1919-20, and Madamin Bey defected to the Soviet side in March.[37] Meanwhile, famine relief reached the region under the more moderate New Economic Policy, while land reform and amnesty placated Ferghana residents. As a result, the Basmachi movement lost control of most populated areas and shrank overall.

The pacification of Ferghana did not last long. During the summer of 1920 the Soviets felt secure enough to requisition food and mobilize Muslim conscripts. The result was a renewed uprising and new Basmachi groups proliferated, fueled by religious slogans.[38] Renewed conflict would see the Basmachi movement spread across Turkestan.

Basmachi in Khiva and Bukhara

In January 1920, the Red Army captured Khiva and set up a Young Khivan provisional government. Junaid Khan fled into the desert with his followers, and the Basmachi movement in the Khorezm Region was born.[39] Before the end of the year, the Soviets deposed the Young Khivans government, and the Muslim nationalists fled to join Junaid, strengthening his forces considerably.[40]

In August of that year, the Emir of Bukhara was finally deposed when the Red Army conquered Bukhara. From exile in Afghanistan, the Emir directed the Bokhara Basmachi movement, supported by the angry populace and clergy. Fighters operated on behalf of the Emir and were under the command of Ibrahim Bey, a tribal leader.[41] Basmachi forces operated with success in both Khiva and Bokhara for an extended period. The insurgency also began spreading to Kazakhstan, as well as the Tajik and Turkmen lands.[40]

Enver Pasha and the height of the Basmachi movement

In November 1921, Enver Pasha, former Turkish war minister and one of the key architects of the Armenian genocide, arrived in Bukhara to assist the Soviet war effort. Enver Pasha had been an advocate of a Turkish-Soviet alliance against the British, and gained the trust of the Soviet authorities. Soon, however, he defected and became the single most important Basmachi leader, centralizing and revitalizing the movement.[41] Enver Pasha intended to create a pan-Turkic confederation encompassing all of Central Asia, as well as Anatolia and Chinese lands.[41] His call for jihad attracted much support, and he managed to transform the Basmachi guerillas into an army of 16,000 men. By early 1922, a considerable part of the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic, including Samarkand and Dushanbe, was under Basmachi control. Meanwhile, Dungan Muslim Magaza Masanchi formed the Dungan Cavalry Regiment to fight for the Soviets against the Basmachi.[42]

Defeat of the movement

Now fearing the total loss of Turkestan, the Soviet authorities once again adopted a double strategy to crush the rebellion: political reconciliation and cultural concessions along with overwhelming military power. Religious concessions reinstated Sharia law, while Koran schools and waqf lands were restored.[43] Moscow sought to indigenize the fight with the creation of a volunteer militia composed of Muslim peasants, called the Red Sticks, and it is estimated that 15-25 percent of Soviet troops in this region were Muslim.[4] The Soviets primarily relied on thousands of regular Red Army troops, veterans of the Civil War, now bolstered by air support. The strategy of concessions with airstrikes was successful, and when in May 1922 Enver Pasha rejected a peace offer and issued an ultimatum demanding that all Red Army troops be withdrawn from Turkestan within fifteen days, Moscow was well prepared for a confrontation. In June 1922 Soviet units led by General Kakurin (ru) defeated the Basmachi forces in the Battle of Kafrun. The Red Army began to drive the rebels eastwards, retaking considerable territory. Enver himself was killed in a failed last-ditch cavalry charge on August 4, 1922, near Baldzhuan (in present-day Tajikistan). His successor, Selim Pasha, continued the struggle but finally fled to Afghanistan in 1923.

In July to August 1923, a large Soviet offensive succeeded at forcing the Basmachi out of Garm.[44] A Basmachi presence remained in the Ferghana Valley until 1924, and fighters there were led by Kurshirmat, who had renewed the revolt in 1920. British intelligence reported[45] that Kurshirmat possessed forces of 5,000-6,000 men. After years of war, however, popular support for the Basmachi cause was drying up. Peasants wanted to return to work, especially now that Soviet policies had made Turkestan livable again. Kurshirmat's forces shrank to around 2,000, many resorting to banditry,[45] and he soon fled to Afghanistan.[46] Turkestan was at this point exhausted by war. 200,000 people had fled Tajik lands, leaving two-thirds of arable land abandoned. Lesser devastation could be observed in Ferghana.[46]

Cross-border operations in northern Afghanistan

_with_his_followers.jpg.webp)

1929

In January 1929, after coming to power in Afghanistan during the Afghan Civil War (1928–1929), Habibullāh Kalakāni allowed Basmachi insurgents to operate in northern Afghanistan, who then had established themselves in Imanseiide, Khan Abad, Rostaq, Taloqan, Fayzabad by the end of March 1929.[44] In mid-March 1929, two raids were undertaken by the Afghan Basmachi into the Soviet Union, the first into Amu Darya, south-west of Kulyab, and the second was undertaken by Kurbashi Kerim Berdoi with 100 Basmachi troops. Both incursions were defeated.[44] Further incursions were repelled on 17 March and 7 April.[44] On 12 April, Basmachi insurgents successfully crossed the Panj River and captured the town of Togmai. Soon after, this force then reached Dzafr and Kevron. On 13 April, the Basmachi captured Qal'ai Khumb.[44] and a few days later, occupied Gashion, and on the 15th, they captured Vanch, which the Soviets recaptured the next day.[44]

Because of the Basmachi attacks, the Soviet Union dispatched a small force into Afghanistan from Termez on April 15, commanded by Vitaly Primakov, to support ousted Afghan King Amanullah Khan. This Red Army force of 700 to 1,000 eventually took control of the city of Mazar-i-Sharif and Tashqurghan.[47] During the Soviet operation the Basmachi continued raiding across the border, capturing Kalai-Liabob on 20 April, and on 21 April capturing Nimichi, 35 kilometres east of Garm, after an intense battle.[44] Between 20 and 22 April, further Basmachi units crossed into the Soviet Union, one of which made it as far as Tavildara before being turned back by the guards there on 30 April. On 22 April, the Basmachi captured Garm, which the Soviets recaptured either the same day or the next day. On 24 April, the Soviets began a large counteroffensive, and recaptured Kalai-Liabob that same day. On 3 May, the last Basmachi units retreated into Afghanistan.[44]

The Red Army had planned to head for Kabul to take it back from the Saqqawists to Amanullah Khan.[48] However the operation was halted after Moscow heard that Amanullah Khan had fled to the British Raj in exile on 23 May.[49] In addition, international resentment (at a time the Soviet Union attempted to gain international recognition) was also cited as a reason for canceling the operation.[48] The last Soviet unit crossed back from Afghanistan in June 1929.[48]

1930

After the Saqqawists lost the civil war and Kalakani was executed, the Afghan prime minister Mohammad Hashim Khan on behalf of the new king, Mohammed Nader Shah, demanded Ibrahim Bek to lay down arms against the Soviet Union, but he refused.[50] Afghanistan and Soviet Union agreed for another intervention, launched by the Red Army in June 1930 and commanded by Colonel Yakov Melkumov.[48] The cavalry brigade advanced 50–70 km inland in northern Afghanistan and was carefully controlled as to not "touch" the farms and property of locals as to not affect their nationalistic or religious feelings. This was relatively successful, as the Afghan locals were friendly and guided them. Ibrahim Bek initially wanted to fight but after hearing of the cavalry's strength and lack of local Afghan sympathy, he halted plans. As a result the Soviets did not face organized resistance and managed to eliminate the Basmachis and their accomplices. The yurts in the river valley including the villages of Aq Tepe and 'Aliabad where Basmachis were based, and the Basmachi's properties, were burned down, although the local Afghan population remained untouched. The Basmachis and accomplices lost 839 people, whereas the Soviet army had one loss (from drowning) and two injuries.[51][52]

Intermittent Basmachi operations after the Soviet victory

After the Basmachi movement was destroyed as a political and military force, the fighters who remained hidden in mountainous areas conducted a guerrilla war. The Basmachi uprising had died out in most parts of Central Asia by 1926. However, skirmishes and occasional fighting along the border with Afghanistan continued until the early 1930s. Junaid Khan threatened Khiva in 1926, but was finally exiled in 1928.[46] Two prominent commanders, Faizal Maksum and Ibrahim Bey, continued to operate out of Afghanistan and conducted a number of raids into the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic in 1929. Ibrahim Bek led a brief resurgence of the movement when collectivization fuelled resistance and succeeded in delaying the policy until 1931 in Turkmenistan, but he was soon caught and executed. The movement then largely died out.[44][53] The last major Basmachi combat operation occurred In October 1933, when Junaid Khan's forces were defeated in the Karakum desert. The Basmachi movement had ended by 1934.[54]

Aftermath

Indigenous leaders began to cooperate with Soviet authorities and large numbers of Central Asians joined the Soviet Communist Party under Lenin and Stalin's indigenization policy. Many gained high positions in the governments of the Uzbek, Tajik, Kyrgyz, Kazakh and Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republics, formed out of the Turkestani Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in 1924. During the Sovietization of Central Asia, Islam became the focus of antireligious campaigns. The government closed most mosques, repressing Islamic clerics and targeting symbols of Islamic identity such as the veil.[55] Uzbeks who remained practicing Muslims were deemed nationalist and often targeted for imprisonment or execution. Stalinist collectivization and industrialization proceeded as elsewhere in the Soviet Union.

Character of the movement

The Basmachi movement has been characterized as a national liberation movement[56] that sought to end foreign rule over the Central Asian territories then known as Turkestan, and also the protectorates of Khiva and Bokhara. It is suggested that "basmacı" is a Turkic word which refers to a bandit or marauder, such as the bands of thieves that preyed on caravans in the region, derived from the word basmak - to raid, to press. The term Basmachi was often used in Soviet sources because of its pejorative meaning.[57]

The Soviets portrayed the movement as being composed of brigands motivated by Islamic fundamentalism, waging a counterrevolutionary war with the support of British agents.[58] In reality, the Basmachi were a diverse and multi-faceted group that received negligible foreign aid. The Basmachi were not viewed favorably by Western Powers, who saw the Basmachi as potential enemies due to the Pan-Turkist and Pan-Islamist ideologies that some of their leaders ascribed to. However, some Basmachi groups received support from British and Turkish intelligence services and in order to cut off this outside help, special military detachments of the Red Army masqueraded as Basmachi forces and successfully intercepted supplies.

Although many fighters were motivated by calls for jihad,[59] the Basmachi drew support from many ideological camps and major sectors of the population. At some point or another the Basmachi attracted the support of Jadid reformers, pan-Turkic ideologues and leftist Turkestani nationalists.[60] Peasants and nomads, long opposed to Russian colonial rule, reacted with hostility to anti-Islamic policies and Soviet requisitioning of food and livestock. The fact that Bolshevism in Turkestan was dominated by Russian colonists in Tashkent[61] made Tsarist and Soviet rule appear identical. The ranks of the Basmachi were filled with those left jobless by poor economic conditions, and those who felt that they were opposing an attack on their way of life.[62] The first Basmachi fighters were bandits, as their name suggests, and they reverted to brigandage as the movement fizzled later on.[46] Although the Basmachi were relatively united at certain points, the movement suffered from atomization overall. Rivalry between various leaders and more serious ethnic disputes between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks or Turkmen posed major problems to the movement.

In popular culture

The rebellion is featured in several "Osterns", such as White Sun of the Desert, The Seventh Bullet, and The Bodyguard, and in the television series State Border.

See also

References

- In Union with him and Bey Madamin counter-revolutionary robber bands with July 10, 1919, to January 1920.

- Muḥammad, Fayz̤; Hazārah, Fayz̤ Muḥammad Kātib (1999). Kabul Under Siege: Fayz Muhammad's Account of the 1929 Uprising. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 9781558761551.

- Supporters of Habibullah had fought in alliance with such films only in northern Afghanistan

- Moscow's Muslim Challenge: Soviet Central Asia, Michael Rywkin, page 35

- Soviet Disunion: A History of the Nationalities Problem in the USSR, By Bohdan Nahaylo,Victor Swoboda, p. 40, 1990.

- Krivosheev, Grigori (Ed.), Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century '12,827 killed or dead', p. 43, London: Greenhill Books, 1997.

- General-Lieutenant G.F.KRIVOSHEYEV (1993). "SOVIET ARMED FORCES LOSSES IN WARS,COMBAT OPERATIONS MILITARY CONFLICTS" (PDF). MOSCOW MILITARY PUBLISHING HOUSE. p. 56. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- Uzbekistan, By Thomas R McCray, Charles F Gritzner, pg. 30, 2004, ISBN 1438105517.

- Martha B. Olcott, The Basmachi or Freemen's Revolt in Turkestan, 1918-24, 355.

- Baberowski & Doering-Manteuffel 2009, p. 202.

- Morrison, Alexander (2017). "The Revolt of 1916 in Russian Central Asia. By Edward Dennis Sokol . Foreword by S. Frederick Starr . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016 (original edition 1954). x, 187 pp. Bibliography. Index. Figures". Slavic Review. 76 (3): 772–778. doi:10.1017/slr.2017.185. ISSN 0037-6779. S2CID 166171560.

- Parenti, Christian (28 June 2011). Tropic of Chaos: Climate Change and the New Geography of Violence. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-56858-662-5.

These traditionalist, protomujahideen—called Basmachi, meaning "bandits", by the Soviets— described themselves as standing for Islam, Turkic nationalism, and anticommunism. One of these bands of Muslim rebels was led by Enver Pasha, ...

- Victor Spolnikov, "Impact of Afghanistan's War on the Former Soviet Republics of Central Asia", in Hafeez Malik, ed, Central Asia: Its Strategic Importance and Future Prospects (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994), 101.

- Michael Rywkin, Moscow's Muslim Challenge: Soviet Central Asia (Armonk: M. E. Sharpe, Inc, 1990), 41.

- Martha B. Olcott, "The Basmachi or Freemen's Revolt in Turkestan, 1918-24," Soviet Studies, Vol. 33, No. 3 (Jul., 1981), 361.

- Abdullaev, Kamoludin (10 August 2018). Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-0252-7.

The uprising spread, and as it gained strength, the Bolsheviks began to refer to its fighters as Basmachi, meaning "bandit" in the local tongues. As they prepared for the Hisor Expedition in the fall of 1920, Turkfront commanders viewed it as ...

- Hiro, Dilip (November 2011). Inside Central Asia: A Political and Cultural History of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz stan, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Iran. Abrams. ISBN 978-1-59020-378-1.

The Communists' major problem now was how to counter the continuing nationalist Basmachi (meaning "bandit" in Uzbek) movement.

- Basmachi Movement From Within: Account of Zeki Velidi Togan

- Goodson, Larry P. (28 October 2011). Afghanistan's Endless War: State Failure, Regional Politics, and the Rise of the Taliban. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80158-2.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, in "Muslim Communities Reemerge: Historical Perspectives on Nationality, Politics, and Opposition in the Former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia", Editors: Andreas Kappeler, Gerhard Simon, Gerog Brunner, 1994, pg. 280.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, in "Muslim Communities Reemerge: Historical Perspectives on Nationality, Politics, and Opposition in the Former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia", Editors: Andreas Kappeler, Gerhard Simon, Gerog Brunner, 1994, pg. 282.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, in "Muslim Communities Reemerge: Historical Perspectives on Nationality, Politics, and Opposition in the Former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia", Editors: Andreas Kappeler, Gerhard Simon, Gerog Brunner, 1994, pg. 284.

- Catherin Evtuhov, Richard Stites, A History of Russia: Peoples, Legends, Events, Forces (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004), 265

- Hafeez Malik, Central Asia, p.101.

- Baberowski & Doering-Manteuffel 2009, pp. 201–202.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, 186.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, 290.

- Martha B. Olcott, The Basmachi or Freemen's Revolt in Turkestan, 1918-24, 354.

- Michael Rywkin, Moscow's Muslim Challenge, 22.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, 291.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, 293.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, 32.

- Michael Rywkin, Moscow's Muslim Challenge, 24.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, 295.

- Martha B. Olcott, The Basmachi or Freemen's Revolt in Turkestan, 1918-24, 356.

- Michael Rywkin, Moscow's Muslim Challenge, 34.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, 296.

- Michael Rywkin, Moscow's Muslim Challenge, 35.

- Fazal-Ur-Rahim Khan Marwat, The Basmachi Movement in Soviet Central Asia, 160.

- Michael Rywkin, Moscow's Muslim Challenge, 36.

- Martha B. Olcott, The Basmachi or Freemen's Revolt in Turkestan, 1918-24, 358.

- Joseph L. Wieczynski (1994). The Modern encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet history, Volume 21. Academic International Press. p. 125. ISBN 0-87569-064-5. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- Martha B. Olcott, The Basmachi or Freemen's Revolt in Turkestan, 1918-24, 357.

- Ritter, William S (1990). "Revolt in the Mountains: Fuzail Maksum and the Occupation of Garm, Spring 1929". Journal of Contemporary History 25: 547. doi:10.1177/002200949002500408.

- Yılmaz Şuhnaz, "An Ottoman Warrior Abroad: Enver Paşa as an Expatriate." Middle Eastern Studies 35, no. 4 (1999), pp. 47-30

- Michael Rywkin, Moscow's Muslim Challenge, 42.

- Larry P. Goodson (2011). Afghanistan's Endless War. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295801582.

- J. Bruce Amstutz (1994). Afghanistan: The First Five Years of Soviet Occupation. DIANE Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 9780788111112.

- Rodric Braithwaite (2011). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan 1979-89. Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780199911516.

- "История в лицах. "Наполеон из Локая". Часть II". abdunazarov.ru. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- "Павел Аптекарь".

- History of the Afghan War in the 1990s and the transformation of Afghanistan into the source of threats to Central Asia

- Ritter, William S (1985). "The Final Phase in the Liquidation of Anti-Soviet Resistance in Tadzhikistan: Ibrahim Bek and the Basmachi, 1924-31". Soviet Studies 37 (4).

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2013-10-29). Encyclopedia of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency: A New Era of Modern Warfare: A New Era of Modern Warfare. ABC-CLIO. p. 61. ISBN 9781610692809.

- Pipes, Richard (1955). "Muslims of Soviet Central Asia: Trends and Prospects (Part I)". Middle East Journal. 9 (2): 149–150. JSTOR 4322692.

- Moscow's Muslim Challenge: Soviet Central Asia, Michael Rywkin, page 43.

- Basmachis - Oxford Islamic Studies Online

- Richard Lorenz, "Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley," in Andreas Kappelerm Gerhard Simon, Edward Allworth, ed, Muslim Communities Reemerge: Historical Perspectives on Nationality, Politics, and Opposition in the Former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia (Durham: Duke University Press, 1994), 277.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, 293

- Martha B. Olcott, "The Basmachi or Freemen's Revolt in Turkestan, 1918-24," Soviet Studies, Vol. 33, No. 3 (Jul., 1981), 252.

- Richard Lorenz, Economic Bases of the Basmachi Movement in the Ferghana Valley, 289.

- Fazal-Ur-Rahim Khan Marwat, The Basmachi Movement in Soviet Central Asia (A Study in Political Development) (Peshawar, Emjay Books International: 1985), 151.

Bibliography

- Baberowski, Jörg; Doering-Manteuffel, Anselm (2009). Geyer, Michael; Fitzpatrick, Sheila (eds.). Beyond Totalitarianism: Stalinism and Nazism compared. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89796-9.

Further reading

- Marie Broxup: The Basmachi. Central Asian Survey, Vol. 2 (1983), No. 1, pp. 57–81.

- Marco Buttino: "Ethnicité et politique dans la guerre civile: à propos du 'basmačestvo' au Fergana", Cahiers du monde russe et sovietique, Vol. 38, No. 1–2, (1997)

- Sir Olaf Caroe: Soviet Empire: The Turks of Central Asia and Stalinism 2nd ed., London, Macmillan (1967) ISBN 0-312-74795-0

- Joseph Castagné. Les Basmatchis: le mouvement national des indigènes d'Asie Centrale depuis la Révolution d'octobre 1917 jusqu'en octobre 1924. Paris: Éditions E. Leroux, 1925.

- Mustafa Chokay: "The Basmachi Movement in Turkestan", The Asiatic Review Vol.XXIV (1928)

- Pavel Gusterin: История Ибрагим-бека. Басмачество одного курбаши с его слов. — Саарбрюккен: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2014. — 60 с. — ISBN 978-3-659-13813-3.

- Б. В. Лунин: Басмачество Tashkent (1984)

- Glenda Fraser: "Basmachi (parts I and II)", Central Asian Survey, Vol. 6 (1987), No. 1, pp. 1–73, and No.2, pp. 7–42.

- Baymirza Hayit: Basmatschi. Nationaler Kampf Turkestans in den Jahren 1917 bis 1934. Köln, Dreisam-Verlag (1993)

- M. Holdsworth: "Soviet Central Asia, 1917–1940", Soviet Studies, Vol. 3 (1952), No. 3, pp. 258–277.

- Alexander Marshall: "Turkfront: Frunze and the Development of Soviet Counter-insurgency in Central Asia" in Tom Everett-Heath (Ed.) "Central Asia. Aspects of Transition", RoutledgeCurzon, London, 2003; ISBN 0-7007-0956-8 (cloth) ISBN 0-7007-0957-6 (pbk.)

- Яков Нальский: В горах Восточной Бухары. (Повесть по воспоминаниям сотрудников КГБ) Dushanbe (1984)

- Martha B. Olcott: "The Basmachi or Freemen's Revolt in Turkestan 1918-24", Soviet Studies, Vol. 33 (1981), No. 3, pp. 352–369.

- Hasan B. Paksoy, "BASMACHI": Turkish National Liberation Movement 1916–1930s, Archived 2017-02-01 at the Wayback Machine Modern Encyclopedia of Religions in Russia and the Soviet Union (FL: Academic International Press) 1991, Vol. 4, pp. 5–20.

- Zeki Velidi Togan, Memoirs.

- Fazal-ur-Rahim Khan Marwat: The Basmachi movement in Soviet Central Asia: A study in political development., Peshawar, Emjay Books International (1985)

- Zeki Velidi Togan, Memoirs: National Existence and Cultural Struggles of Turkistan and Other Muslim Eastern Turks (2011) Full Text translation from the 1969 original. Translated by Paksoy.

- Х. Турсунов: Восстание 1916 Года в Средней Азии и Казахстане. Tashkent (1962)