Alash Autonomy

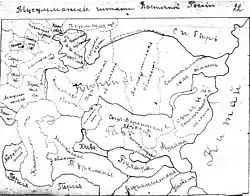

The Alash Autonomy (Kazakh: Алаш Автономиясы, romanized: Alaş Avtonomiasy, Kazakh pronunciation: [ɑlɑɕ ɑftonomɪjɑsɯ]; Russian: Алашская автономия, Alashskaya avtonomiya), also known as Alash Orda (Kazakh: Алаш Орда, romanized: Alaş Orda; Russian: Алаш-Орда, romanized: Alash-Orda) was a Kazakh provisional government, or proto-state, located mainly in Central Asia, and partly in Eastern Europe. It was part of the Russian Republic, and then Soviet Russia. The Alash Autonomy was founded in 1917 by Kazakh elites, and disestablished after the Bolsheviks banned the ruling Alash party. The goal of the party was to obtain autonomy within Russia, and to form a national, democratic state. The political entity bordered Russian territories to the north and west, the Turkestan Autonomy to the south, and China to the east.

Alash Autonomy | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1917–1920 | |||||||||||||

Seal

| |||||||||||||

| Motto: Оян, Қазақ! Oian, Qazaq! Проснись, казах! Wake up, Kazakh! | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized autonomy of Russia | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Alash-Qala | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Kazakh Russian | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Secular[6] | ||||||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||

• 1917-1920 | Alikhan Bukeikhanov | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Russian Civil War | ||||||||||||

• Established | December 1917 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 17 August 1920 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Kazakhstan Russia | ||||||||||||

Ethnonym

The use of the word Alash spreads a lot in Kazakh culture. Most commonly, Alash is the group of three juzes, territorial and tribal divisions of Kazakhs. It means that the name of autonomy can be used as a synonym to Kazakh. The ruling party wanted autonomy to unite all Turkic people from Central Asia, however the idea failed, as after several negotiations, congresses became a scene to show the unity of the Turks rather than serious talks about pan-Turkism.

History

Kazakhs, tired of almost a century of Russian colonization, started to rise up. In the 1870s-80s, schools in Kazakhstan massively started to open, which developed elite, future Kazakh members of the Alash party. In 1916, after conscription of Muslims into the military for service in the Eastern Front during World War I, Kazakhs and Kyrgyzs rose up against the Russian government, with uprisings until February 1917.

The state was proclaimed during the Second All-Kazakh Congress held at Orenburg from 5–13 December 1917 OS (18-26 NS), with a provisional government being established under the oversight of Alikhan Bukeikhanov.[7] However, the nation's purported territory was still under the de facto control of the region's Russian-appointed governor, Vasily Balabanov, until 1919. In 1920, he fled the Russian Red Army for self-imposed exile in China, where he was recognised by the Chinese as Kazakhstan's legitimate ruler.

Following its proclamation in December 1917, Alash leaders established the Alash Orda, a Kazakh government which was aligned with the White Army and fought against the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. In 1919, when the White forces were losing, the Alash Autonomous government began negotiations with the Bolsheviks. By 1920, the Bolsheviks had defeated the White Russian forces in the region and occupied Kazakhstan. On 17 August 1920, the Soviet government established the Kirghiz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which in 1925 changed its name to Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic, and finally to Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic in 1936.[8]

Government

Alash Orda (Kazakh: Алаш Орда, "Alash Horde") was the name of the provisional Kazakh government from 13 September 1917 to 1918. This provisional government consisted of twenty-five members: ten positions reserved for non-Kazakhs and fifteen for ethnic Kazakhs.[9] During their rule, the Alash Orda formed a special educational commission and established militia regiments as their armed forces. They issued a number of legislative resolutions.

Alongside the authority of the Alash Orda, independent Bolshevik councils sprang up which opposed the body's rule and aligned themselves with Vladimir Lenin in the brewing Russian Civil War. By 1919, the legitimate government of the Alash Autonomy had been effectively dismantled by Soviet forces, its territory being integrated into the nascent Soviet Union. On 17 August 1920, the Kirghiz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed by Lenin and Mikhail Kalinin; this would eventually become the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic and would remain the functioning authority in the region until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late-1980s.

Films

- 1994 «Алаш туралы сөз» "The Word About Alash" "Алаш туралы сөз" - "Алаш туралы сөз" (documentary) «Kazakhtelefilm» film director Kalila Umarov.

- 2009 «Алашорда» "Alashorda" "Алашорда" - "Алашорда" (documentary) «Kazakhfilm» film director Kalila Umarov.

- 2018 " Тар заман "- Tar zaman " Strait time" (serial) by Kazakhstan national channel- Қазақстан ұлттық арнасы

See also

References

- Каким был государственный флаг Автономии Алаш?

- ЗАКИ ВАЛИДИ И НАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ ИНТЕЛЛИГЕНЦИЯ КАЗАХСТАНА

- Башкирское национальное движение (1917—1921 гг. p. 179

- ЗАКИ ВАЛИДИ И НАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ ИНТЕЛЛИГЕНЦИЯ КАЗАХСТАНА

- Башкирское национальное движение (1917—1921 гг. p. 179

- The Alash Movement and the Soviet Government: A Difference of Positions

- Ubiria, Grigol (16 September 2015). Soviet Nation-Building in Central Asia:The Making of the Kazakh and Uzbek Nations. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 9781317504351. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- Peimani, Hooman (2009). Conflict and Security in Central Asia and the Caucasus. ABC-CLIO. p. 124. ISBN 9781598840544. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- Adle, Chahryar (2005). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Towards the contemporary period: from the mid-nineteenth to the end of the twentieth century. UNESCO. pp. 255–256. ISBN 9789231039850. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- Galick, David. Responding to the Dual Threat to Kazakhness: The Rise of Alash Orda and its Uniquely Kazakh Path, Vestnik: The Journal of Russian and Asian Studies (March 29, 2014)