Bataireacht

In Irish martial arts, bataireacht (pronounced [ˈbˠat̪ˠəɾʲaxt̪ˠ]; meaning 'stick-fighting') (also called boiscín and ag imirt na maidí [1]) refers to a form of stick-fighting from Ireland. Although an old term, it was used by author John W. Hurley and introduced into modern English usage in the late 1990’s.

| Also known as | Bata, Boiscín, Irish stick-fighting, ag imirt na maidí |

|---|---|

| Focus | Stick-fighting |

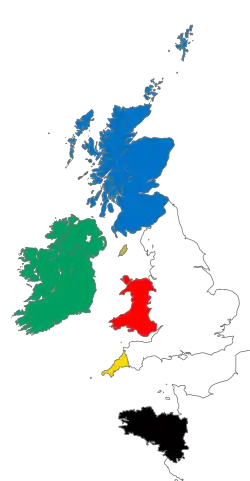

| Country of origin | Ireland |

| Olympic sport | No |

Definition

Bataireacht is a category of stick-fighting martial arts of Ireland. Bata is the Irish term for stick. The actual bata used for bataireacht is commonly called a shillelagh.

There are a two theories as to the origin of the word "shillelagh". The most popular one is that the name came from a genericization of the forest of Shillelagh, a barony situated in County Wicklow, and famous for its oak forests in the 18th century. As the oak coming from this region was in high demand, the term started to be applied to good quality sticks. This is the meaning that many authors of the 18th and 19th centuries used when talking about shillelaghs, for example William Carleton who talked of cudgels made of "good shillelah".[2] The first documentable use of the word “Shillelagh” in English, was in 1755, in Thomas Sheridan's The Brave Irishman[3] the expression there is used side to side with "Andreaferrara" by the protagonist to refer to his sword in the same manner as he refers to "Shillela", hinting at a genericization. This explanation can be found in many different sources from the 18th and 19th centuries, and is considered the most popular one. Another theory was brought up by Patrick S. Dinneen in the 1927 edition of his Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla dictionnary. Dinneen briefly notes that Sail Éille means "thonged cudgel", and seems to allude it was later anglicized as shillelagh. Various linguists borrowed his theory throughout the years, but it was also dismissed by other scholars for its lack of a rationale.

Common woods used to make sticks included Blackthorn, oak, ash and hazel were traditionally the most common types of woods used to make shillelagh fighting sticks.[4]

The style is mostly characterized by the use of a cudgel, or knobbed stick, of different lengths but most often the size of a walking stick. The stick is grabbed by the third of the handle end, the lower part protecting the elbow and allowing the user to maintain an offensive as well as defensive guard. This grip also allows launching fast punching-like strikes.[5]

History

The Irish have used various sticks and cudgels as weapons of self-defence for centuries. [6] As with most vernacular martial arts, it is difficult to establish the origin of the art. The art certainly goes back to prehistory and possibly was widespread in the Bronze Age when metal was highly precious yet sticks were easily obtained. Weapons similar to shillelagh are described in various sources including heroic tales such as The Destruction of Da Derga's Hostel [7] and were also popular all over Europe [8] It would truly begin to catch the attention of writers in the 18th century. The shillelagh is still identified with Irish popular culture to this day, although the arts of bataireacht are much less so. The sticks used for bataireacht are not of a standardised size, as there are various styles of bataireacht, using various kinds of sticks.

The historical link between bataireacht and other Irish weapons is unclear. Some authors have argued that prior to the 19th century, the term had been used to refer to a form of stick-fencing used to train Irish soldiers in broadsword and sabre techniques.[9] This theory has been criticized, among other things for its lack of primary source material. Although fencing instruction and manuals existed at the time and were available in Ireland and abroad, with one of them illustrating bataireacht among wrestling, boxing and fencing [10] the two systems are in practice substantially different, namely in the active use of the buta, a part of the stick with no equivalent in European swords. Clues indicate that links may exist with other weapons closer in attributes such as the axe, but the historical descriptions are rare and limited in scope, so it is quite difficult to confirm. [11]

By the 18th century bataireacht became increasingly associated with Irish gangs called "factions". Irish faction fights involved large groups of men (and sometimes women) who engaged in melees at county fairs, weddings, funerals, or any other convenient gathering. Historians such as Carolyn Conley, believe that this reflected a culture of recreational violence. It is also argued that faction fighting had class and political overtones, as depicted for example in the works of William Carleton and James S. Donnelly, Jr.'s "Irish Peasants: Violence & Political Unrest, 1780".

By the early 19th century, these gangs had organised into larger regional federations, which coalesced from the old Whiteboys, into the Caravat and Shanavest factions. Beginning in Munster the Caravat and Shanavest "war" erupted sporadically throughout the 19th century and caused some serious disturbances.[12]

As the faction fights became increasingly repressed by society and other sports such as hurling were promoted, bataireacht slowly faded in importance in Irish popular culture by the turn of the 20th century.[13] Although still documented sporadically, it has become mostly an underground practice saved by a few families who handed down their own styles.

Modern practice

The modern practice of bataireacht has arisen amongst some practitioners from a desire to maintain, reinstate or re-invent Irish family traditions. Bataireacht has also gained popularity amongst non-Irish people, as a form of self-defence, as a cane or walking stick can be easily carried in modern society.

A few forms of bataireacht survive to this day, some of which are traditional styles specific to the family which carried them down through the years, like the rince an bhata uisce beatha ('dance [of] the whiskey stick') style of the Doyle family of Newfoundland, taught in Canada, Ireland, the United Kingdom, the United States and Germany, or Antrim Bata which is currently taught in seven countries.[14]

Additionally, members of the Western martial arts movement have reconstructed styles using period martial arts manuals, historical newspaper articles, magazines, pictorial evidence and court documents. Surviving instructional manuals which describe some use of the shillelagh include those by Rowland Allanson-Winn and Donald Walker.

See also

References

- O'Begly, Conor (1732). An Focloir Bearla Gaoidheilge. Bar na chur acclodh le Seumas Guerin, an bhiadhain dloir an tiaghurna. p. 145.

- Carleton, William (1834). Tales of Ireland. William Curry, Jun. and company. p. 363.

- Sheridan, Thomas (1755). The Brave Irishman. J. Baillie and co. p. 14.

- Hurley, John W. (2007). The Shillelagh Makers Handbook. Caravat Press.

- Chouinard, Maxime (3 February 2015). "What is Irish stick fighting?". Hemamisfits.com. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Hurley, John W. (2007). Shillelagh: The Irish Fighting Stick. Caravat Press. p. 347. ISBN 978-1-4303-2570-3.

- Stokley, Whiteley (1910). Epic and saga. P. F. Collier & Son. p. 226.

- Chouinard, Maxime (28 May 2021). "Getting medieval: Just how old is Irish stick fighting?". Irishstick.com. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- O'Donnell, Patrick D. (1975). The Irish Faction Fighters of the 19th Century. Anvil Press.

- Walker, Donald (1840). Defensive Exercises. Thomas Hurst. p. 62.

- Chouinard, Maxime (23 June 2021). "Shillelagh: How fencing influenced (or not) Antrim Bata". Irishstick.com. Irishstick.com. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- Clark, Samuel; James S. Donnelly (1983). Irish Peasants: Violence & Political Unrest, 1780–1914. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-09374-3.

- Hurley, John W. (2007). Shillelagh: The Irish Fighting Stick. Caravat Press. p. 347. ISBN 978-1-4303-2570-3.

- "Irish Stick". Irishstick.com. Retrieved 24 March 2023.