Battle of Arachova

The Battle of Arachova (Greek: Μάχη της Αράχωβας), took place between 18 and 24 November 1826 (N.S.). It was fought between an Ottoman Empire force under the command of Mustafa Bey and Greek rebels under Georgios Karaiskakis. After receiving intelligence of the Ottoman army's maneuvers, Karaiskakis prepared a surprise attack in vicinity of the village of Arachova, in central Greece. On 18 November, Mustafa Bey's 2,000 Ottoman troops were blockaded in Arachova. An 800-man force that attempted to relieve the defenders three days later failed.

| Battle of Arachova | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greek War of Independence | |||||||

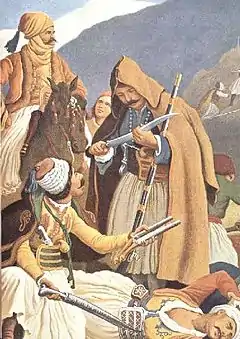

The Battle of Arachova by Peter von Hess | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 950 | 2,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

12 killed 20 injured |

1,700 killed 50 captured | ||||||

On 22 November Mustafa Bey was mortally wounded and Ottoman morale plunged, as cold weather and heavy rainfall plagued the hunger-stricken defenders. At midday on 24 November the Ottomans made a disastrous attempt at breaking out. Most were killed in the fighting or perished from the cold. The Greek victory at Arachova gained the rebels valuable time before the Great Powers came to their assistance a year later.

Background

In February 1821, Filiki Eteria launched the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire.[2] By 1826, the First Hellenic Republic had been severely weakened by infighting and Ibrahim's invasion of Mani. Ibrahim's well-trained Egyptian army pillaged much of Morea, turning the tide of the war in the favor of the Ottomans.[3] Following the decisive Ottoman victory at the Third Siege of Missolonghi on 10 April 1826, fighting was restricted to the Siege of the Acropolis. The Ottomans seemed to have gained the upper hand in Central Greece, with many Greek rebels accepting Grand Vizier Mehmed Reshid Pasha's amnesty in order to take a break from the hardships of the war.[4] Defeatism affected a number of Moreote Christian notables (kodjabashis) who began advocating for peace in return for a limited autonomy such as the one granted by the Ottomans to Wallachia after the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1806.[5]

In October 1826, Greek general Georgios Karaiskakis took a number of fighters who managed to break out from Missolonghi, heading south-east towards Morea. On 27 October he arrived at Domvrena, besieging the 300-man Ottoman garrison who had taken refuge in tower houses. On 14 November, Karaiskakis broke off the siege after receiving news that Mustafa Bey's 2,000-man army (including 300 cavalrymen)[4] had begun its descent from Livadeia towards Amfissa, in order to relieve the latter's garrison and protecting the Ottoman gunpowder dump at Atalanti;[6] putting the Greek forces in the area in grave danger. On the early morning of 16 November, Karaiskakis reached the Hosios Loukas monastery, spending the rest of the day there. Shortly before the dawn of 17 November, Greek troops set camp at Distomo. On the same day Mustafa Bey dispersed Greek pickets at Atalanti, later camping at the Agia Ierousalim monastery outside Davleia.[7]

There he questioned the monastery's hegumenos about Karaiskakis' whereabouts and whether he knew of his intention to relieve Amfissa. The hegumenos lied, claiming that Karaiskakis had yet to leave Domvrena and that he was oblivious to the Ottoman maneuvers. Mustafa Bey believed him, nevertheless ordering his soldiers to keep an eye on the monks and promising to execute them should one of them try to betray his presence at the monastery. As Mustafa Bey and his lieutenant (kehaya) were discussing their future plans while dining, a monk who was fluent in Turkish overheard their conversation. The monks convened in secret, deciding to dispatch one of their number to Distomo and inform Karaiskakis of the route the Turks were to take. A young monk named Panfoutios Charitos managed to evade the Turkish sentries, inform Karaiskakis, and, again evading the Turkish guards, return to his bed before the Turks recounted the number of the monks present in the next morning.[8]

Karaiskakis immediately ordered his officers Georgios Hatzipetros, Alexios Grivas and Georgios Vagias to occupy the church of Agios Georgios in Arachova and the surrounding houses. They were to strike the Turks with a force of 500 men once their enemies emerged from the passes of Mount Parnassus. Small bands were stationed between Arachova and Distomo in order to signal the outbreak of hostilities, at which point the main force would come to their aid. Christodoulos Hatzipetros and his unit of 400 men covered a passage south of Arachova. Karaiskakis' secretary then sent messages to all known guerrilla bands in the surrounding areas, informing them of the impending battle.[9]

Battle

At 10:00 on 18 November, Greek lookouts signaled that the Turks were approaching Arachova from the north–east. An advanced column of Turks arrived at the village and was waiting for the rest of the army when Albanian soldiers in Ottoman service noticed that several houses had freshly carved loopholes. Taking cover behind huge rocks standing inside the village they initiated a firefight with the Greeks. This came as a surprise to the majority of the villagers who had remained oblivious of the situation until the last minute; they now fled in panic in fear of future reprisals.[10] The Turks continued to funnel fresh troops into the village, steadily approaching the Greek positions which were the source of continuous volleys of shots. In the meantime Christodoulos Hatzipetros' troops redeployed to the Kumula hill overlooking the village from the south. Karaiskakis' troops appeared on the outskirts of Arachova around midday, and rebels from the surrounding areas gathered west of the village, thus completely encircling the Turks. Mustafa Bey reacted by sending a detachment of 500 infantrymen to hold Karaiskakis' advance. The rest of the Turkish army occupied a hill overlooking the village, while the detachment barricaded themselves inside the nearby houses.[11]

Upon descending the Mavra Litharia hillock the Greeks under Karaiskakis were engaged by the Turkish detachment that had stayed behind in the village. A quarter of an hour later the Turks had successfully repelled the attack from the hillock, moreover the Greek right flank broke ranks and fled. The situation was reversed when a unit of Souliotes under Georgios Tzavelas mounted a second offensive, killing a Turkish officer and rallying deserters to return to the battlefield. Morale in the Turkish right flank plunged, those who managed to escape were intercepted west of the village and annihilated. Yet the Ottoman center and left flank held fast and Karaiskakis sought other ways to break the stalemate. 300 Greeks under Giotis Danglis passed west of the Zervospilies hill, taking a hill which overlooked the one the main Turkish force had occupied. This came as a complete surprise to Mustafa Bey, who led a Turkish counter attack, sword in hand. Being favored by the terrain, the Greeks crushed three waves of attackers within half an hour. In the meantime Karaiskakis overcame the resistance that faced him, joining his comrades in arms at the Agios Georgios church. The Turkish camp was surrounded and besieged just as night fell and hostilities were suspended.[12]

On 19 November, the two sides exchanged fire, causing only minor damage to each other's barricades. The rest of the day was uneventful. In the early hours of 20 November, the Greeks received 450 men in reinforcements, most of them were sent on guard duty to the roads leading to Arachova. On 21 November, 800 soldiers under Abdullah Agha appeared outside Davleia where they broke into two forces. The smaller marched down to the Agia Ierousalim monastery while the larger headed towards Zemeno. Zemeno was to be the point where Abdullah Agha would strike the Greek rear, enabling Mustafa Bey to break out of the encirclement. The first formation was to act as a distraction.[13]

Mustafa Bey's troops hurriedly attacked Zemeno before Abdullah Agha's arrival and were pushed back. In the meantime, Abdullah Agha's vanguard was ambushed at a narrow passage leading to Zemeno. 30 Turks were killed and many were wounded before a disorganized retreat was conducted; the rebels captured 80 animals packed with supplies. The situation in the Turkish camp was desperate, as cold weather and heavy rainfall plagued the hunger-stricken defenders. His soldiers pressured Mustafa Bey into negotiations. Karaiskakis demanded that the Turks hand over all their weapons and money, give the kehaya's and Mustafa Bey's brother as hostages, and abandon Livadeia and Amfissa, promising safe passage in return. The terms were rejected, by a messenger who exclaimed "War!" three times. In the morning of 22 November, Karaiskakis ordered salvos to be fired on the Turkish camp from all sides.[14]

Mustafa Bey, who had emerged from his tent to encourage his troops, was mortally wounded in the forehead. On the following day the kehaya assumed command, as a snowstorm swept through the area. Once Mustafa Bey's condition became known to his officers, the Albanian officers threatened to lay down arms unless the terms of the Greeks were satisfied.[15] On the midday of 24 November, 700 Ottomans charged at a small picket guarding the road towards the Agia Ierousalim monastery. At the same time, Abdullah Aga ordered the retreat of his forces. Although the initial breakout was successful, the Greeks regrouped, splitting the Turks in half. The 500 Turks who still held the camp were surrounded and slain, as were most of those who broke out. The soldiers who encountered the kehaya ignored his pleas for mercy as they did not speak Turkish, killing him.[16]

Aftermath

Out of the initial force of 2,000 only 300 Turks survived the onslaught,[17] escaping with the help of a Greek turncoat named Zeligiannaios; most of them perished in the snowstorm.[18] The Greeks took 50 prisoners, most of whom also died from the effects of hypothermia. Greek losses amounted to 12 killed and 20 injured. The Greeks also captured all the pack animals that were still alive, 23 flags and large amounts of weaponry and ammunition. Karaiskakis ordered the construction of a pyramid of 300 severed heads, in accordance with Ottoman tradition. A stone was placed in front of the pyramid bearing the inscription "Tropaion of Greek victory over the barbarians", while the heads of Mustafa Bey and the kehaya were placed on its sides.[19] The severed ears of the slain Ottomans were cured and shipped to the Greek capital of Nafplio, mimicking another Ottoman practice of celebrating significant victories. The victory was widely celebrated in liberated areas of Greece and became the subject of a folk song that was recorded in Karaiskakis' journals.[20]

With this victory at Arachova Karaiskakis kept the revolution alive in eastern Greece. He then sought to disrupt Mehmed Reshid Pasha's supply lines between Thessaly and Attica. On 5 December 1826, his troops destroyed a large Turkish supply convoy at Tourkochori in the vicinity of Atalanti.[21] In the meantime, the Ottomans continued to transfer troops towards south central Greece, aiming at breaking the Greek siege of Amfissa the reinforcing the Ottoman force blockading Acropolis.[22] The victory at Arachova won Greece valuable time[23] before the persistence of the Greek revolutionaries and the war crimes of their adversaries, led the Great Powers to sign the 1827 Treaty of London which resulted in their intervention into the war on Greek side; decisively turning the tide of the war against the Ottomans.[24]

Notes

- Citations

- A. S. Agapitos (1877). "Οι Ένδοξοι Έλληνες του 1821, ή Οι Πρωταγωνισταί της Ελλάδος [The Glorious Greeks of 1821, or the main Personalities of Greece]" (in Greek). Τυπογραφείον Α. Σ. Αγαπητού, Εν Πάτραις [A.S. Agapitos' printing house, in Patras]. pp. 208–216.

- Chrysanthopoulos 2003, p. 336.

- Rotzokos 2003, pp. 164–170.

- Charitos 2001, pp. 17–18.

- Kasomoulis 1941, pp. 316–317.

- Fotiadis 1995, pp. 557–559.

- Charitos 2001, pp. 19–20.

- Fotiadis 1995, pp. 567–570.

- Charitos 2001, pp. 20–24.

- Fotiadis 1995, pp. 573–575.

- Charitos 2001, pp. 26–28.

- Charitos 2001, pp. 28–30.

- Charitos 2001, pp. 31–33.

- Charitos 2001, pp. 33–37.

- Fotiadis 1995, pp. 582–584.

- Charitos 2001, pp. 40–43.

- Jaques 2007, p. 61.

- Fotiadis 1995, pp. 588–589.

- Kokkinos 1974a, pp. 542–543.

- Fotiadis 1995, pp. 595–596, 588.

- Fotiadis 1995, pp. 601–602.

- Fotiadis 1995, pp. 606–608.

- Fotiadis 1995, pp. 592–593.

- Kokkinos 1974b, pp. 139–141.

References

- Charitos, Georgios (2001) [1994]. Η Μάχη της Αράχωβας υπό τον Στρατάρχη Γ.Καραϊσκάκη και οι συντελεσταί της [The Battle of Arachova under Commander G. Karaiskakis and its participants] (in Greek). Athens: Municipality of Arachova. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Chrysanthopoulos, Fotakos (2003). Βίοι Πελοποννήσιων Ανδρών [Lives of Peloponnesean Men] (in Greek). Athens: Eleutheri Skepsis. ISBN 9789608352018.

- Fotiadis, Dimitrios (1995) [1956]. Καραϊσκάκης [Karaiskakis] (in Greek). Athens: S. I. Zacharopoulos. ISBN 960208197X.

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-first Century. Vol. I. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313335372. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Kasomoulis, Nikolaos (1941). Ενθυμήματα Στρατιωτικά Της Επαναστάσεως Των Ελλήνων 1821-1833 [Military Recollections of the Greek Revolution 1821-1833] (in Greek). Vol. II. Athens: Chorigia Pagkeiou Epitropis.

- Kokkinos, Dionysios (1974a). Η Ελληνική Επανάστασις [The Greek Revolution] (in Greek). Vol. V. Athens: Melissa.

- Kokkinos, Dionysios (1974b). Η Ελληνική Επανάστασις [The Greek Revolution] (in Greek). Vol. VI. Athens: Melissa.

- Rotzokos, Nikolaos (2003). "Οι Εμφύλιοι Πόλεμοι (The Civil Wars)". In Panagiotopoulos, Vassilis (ed.). Ιστορία του Νέου Ελληνισμού [History of Modern Hellenism] (in Greek). Vol. III. Athens: Ellinika Grammata. ISBN 9604065408.