Battle of Caldiero (1809)

In the Battle of Caldiero[lower-alpha 2] or Battle of Soave or Battle of Castelcerino from 27 to 30 April 1809, an Austrian army led by Archduke John of Austria defended against a Franco-Italian army headed by Eugène de Beauharnais, the Viceroy of the Kingdom of Italy. The outnumbered Austrians successfully fended off the attacks of their enemies in actions at San Bonifacio, Soave, and Castelcerino before retreating to the east. The clash occurred during the War of the Fifth Coalition, part of the Napoleonic Wars.

| Battle of Caldiero (1809) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Fifth Coalition | |||||||

Eastward-looking view of Soave. Castelcerino is out of the photo to the left along the crest of the ridge while San Bonifacio is a short distance beyond the right edge. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Eugène de Beauharnais | Archduke John | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

San Bonifacio: 3,000 Soave: 23,000 Castelcerino: 5,000 |

San Bonifacio: 1,800 Soave: 18,000 Castelcerino: 6,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

San Bonifacio: light Soave: 1,000 Castelcerino: 409 |

San Bonifacio: light Soave: 700 Castelcerino: 872 | ||||||

In the opening engagements of the war, Archduke John defeated the Franco-Italian army and drove it back to the Adige River at Verona. Forced to detach substantial forces to watch Venice and other enemy-held fortresses, John found himself facing a strongly reinforced Franco-Italian army near Verona. So embarrassed by his setbacks that he tried to minimize them in communications to his step-father Emperor Napoleon, Eugène determined to use his superior forces to drive the Austrian invaders from the Kingdom of Italy.

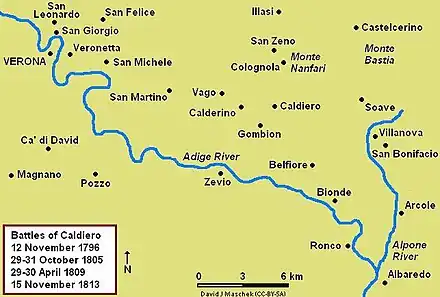

Eugène probed at San Bonifacio on the 27th. On 29 April, he ordered part of his troops to make a holding attack against Soave while he sent an Italian force to seize the high ground on the Austrian right flank. On the 30th, the Austrians recaptured Castelcerino, which was lost the previous day. While this action was being fought, John's army began its retreat to the Brenta River at Bassano. Caldiero is located 15 kilometres (9 mi) east of Verona. The towns of Soave and San Bonifacio lie along the Autostrada A4 about 25 kilometres (16 mi) east of Verona. Castelcerino is a small village in the hills about 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi) north of Soave.

Background

See Sacile 1809 Order of Battle for a list of units and organizations of the Austrian and Franco-Italian armies.[4][5][6]

At the start of the 1809 war, General der Kavallerie Archduke John had authority over Feldmarschallleutnant Johann Gabriel Chasteler de Courcelles's VIII Armeekorps of 24,500 infantry and 2,600 cavalry, and Feldmarschallleutnant Ignaz Gyulai's IX Armeekorps of 22,200 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. The VIII Armeekorps massed at Villach in Carinthia and the IX Armeekorps concentrated to the south at Ljubljana (Laibach) in Carniola, in modern-day Slovenia. General-major Andreas von Stoichevich was detached with 10,000 troops to observe General of Division Auguste Marmont's XI Corps in Dalmatia, which French had held since 1806. A force of 26,000 Landwehr manned garrisons and defended Inner Austria. John wanted the VIII Armeekorps to march southwest from Villach while the IX Armeekorps moved northwest from Laibach. The two forces would join near Cividale del Friuli.[7]

At the start of the war, the Tyrolese people rose in revolt. Under leaders such as Andreas Hofer they started attacking the Bavarian garrisons. Hoping to aid the rebellion, Austrian commander-in-chief Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen ordered John to detach Chasteler and 10,000 Austrian troops to assist the Tyrolese. Chasteler's replacement as the commander of the shrunken VIII Armeekorps was Albert Gyulai, Ignaz Gyulai's brother.[8] Suspecting that Austria planned to initiate a war, Napoleon built up the French part of the Army of Italy to six infantry and three cavalry divisions. Actually, a good many of the so-called French soldiers were Italians, because Napoleon had annexed parts of northwest Italy to the First French Empire. In addition, Eugène assembled three Italian infantry divisions so that the Franco-Italian army numbered 70,000 troops. However, the army was dispersed across northern Italy.[8]

Eugène never led large formations into battle, yet Napoleon appointed him commander of the Army of Italy.[9] To prepare his stepson Eugène for the role, the emperor wrote him many detailed letters advising him how to defend Italy. He urged Eugène to fall back from the Isonzo River line to the Piave River if the Austrians invaded in strength. Napoleon made the point that the Adige River was an extremely important strategic position.[8] He did not believe Austria was going to attack in April and he did not want to provoke his enemy by massing his armies. Thus, Eugène's army remained somewhat dispersed.[10]

On 10 April 1809, the Austrian VIII Armeekorps advanced from Tarvisio while the IX Armeekorps crossed the Isonzo River near Cividale. By the 12th they joined near Udine and pushed to the west. Eugène was compelled to detach Louis Baraguey d'Hilliers and one Italian division to watch the Tyrol.[11] As the Austrians moved west, they detached forces to mask the Franco-Italian fortresses of Palmanova and Osoppo. Believing that he could defeat Archduke John, Eugène ordered his divisions to concentrate at Sacile. By 14 April, he collected the five infantry divisions[12] of Jean Mathieu Seras, Jean-Baptiste Broussier, Paul Grenier, Gabriel Barbou des Courières, and Philippe Eustache Louis Severoli, and the light cavalry division of Louis Michel Antoine Sahuc.[4] Eugène's divisions were not organized into corps, making his army more difficult to control in battle.[12]

In a preliminary action on the 15th, Sahuc's vanguard received a drubbing at Pordenone.[13] Nevertheless, believing he outnumbered John, Eugène attacked the Austrian army in the Battle of Sacile on 16 April.[14] In fact, the Franco-Italian army numbered 35,000 infantry, 2,050 cavalry, and 54 guns, while their opponents deployed 35,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, and between 55 and 61 guns.[13] Eugène sent two divisions against the Austrian left flank, held by VIII Armeekorps. In the face of stubborn resistance, two more divisions were committed to the struggle. When John suddenly launched IX Armeekorps against the weakened French left flank, Eugène called off his attacks and ordered a retreat. The Franco-Italians lost 6,500 men and 15 guns, while the victorious Austrians counted 4,000 casualties.[15]

As the Franco-Italian army fell back to the Piave River, it met Jean Maximilien Lamarque's infantry division and Charles Joseph Randon de Malboissière de Pully's dragoon division moving forward. Eugène used these fresh units to cover his retreat. After holding the line of the Piave for four days, he began a withdrawal to the Adige on 21 April.[16] At this time the army was joined by Teodoro Lechi's Royal Italian Guard.[17] After a pause on the Brenta on the 24th, the retreat was resumed. Anxious for his northern flank, Eugène authorized Baraguey d'Hilliers to fall back to Rovereto. Chasteler followed this up, taking Trento on 23 April and appearing before Rovereto on the 26th.[16]

Deeply embarrassed by his defeat, Eugène made a vague report to Napoleon. But his imperial stepfather soon found out. The infuriated emperor sent Eugène a critical letter suggesting that he ask Marshal Joachim Murat to take command of the army. Fortunately for the viceroy, events soon began to favor the Franco-Italians. After Sacile, Eugène ordered Barbou to reinforce the garrison of Venice with 10 battalions and a cavalry squadron.[18] After detaching 10,000 troops to keep this large force from menacing his communications, John reached the Adige with as few as 28,000 soldiers.[19] Pierre François Joseph Durutte's infantry and Emmanuel Grouchy's dragoon division rendezvoused with the Franco-Italian army near Verona. With 55,500 men available, Eugène prepared to take the offensive.[20]

On 23 April, there was a clash at Malghera near Venice. John ordered Oberst (colonel) Samuel Andreas Gyurkovics von Ivanocz to capture a bridgehead on the Dese River with his 2,000 troops. The Austrian force included nine companies of the Ottocaner Grenz Infantry Regiment, two battalions of the Archduke Franz Infantry Regiment Nr. 52, and six 12-pound guns. Gyurkovics ran into a far superior force under Austerlitz veteran, General of Division Marie-François Auguste de Caffarelli du Falga and was mauled. Caffarelli's troops included three battalions of the 7th Italian Line Infantry Regiment, eight battalions of the 7th, 16th, and 67th Line Infantry Regiments, and 12 guns. The Franco-Italians claimed to have inflicted 600 killed and wounded on their enemies while losing only 20 killed and wounded. Austrian records are absent.[21]

Battle

On the Adige, Eugène reorganized his army into corps under commanders that he nominated and who were approved by Napoleon. General of Division Jacques MacDonald led the V Corps with the divisions of Broussier and Lamarque and a dragoon brigade. He appointed Grenier to take charge of the VI Corps which included the divisions of Durutte and General of Brigade Louis Jean Nicolas Abbé and the 8th Hussars. Abbé was in acting command of Grenier's former division until General of Division Michel Marie Pacthod's arrival. The XII Corps was formed from the divisions of Fontanelli and General of Division Jean-Baptiste Dominique Rusca. When Severoli was wounded at Sacile, Fontanelli transferred from the 2nd to the 1st Italian Division and was replaced by Rusca. The Reserve, under Eugène's personal command, included the Italian Guard, the division of Seras, Jean-Barthélemot Sorbier's artillery reserve, and the three cavalry divisions.[22] Grouchy was placed in command of the cavalry.[23] With pursuit in mind, Eugène created a light brigade by forming three battalions by taking voltiguer companies from the line regiments, while adding a squadron of light cavalry and a section of two cannons. General of Brigade Armand Louis Debroc was appointed to lead the light brigade.[24]

On 27 April, there was a clash at San Bonifacio and Villanova. Seras defended the position with the 106th Line Infantry Regiment, one squadron of cavalry, and four guns, a total of 3,000 men. They were opposed by Oberst (colonel) Anton von Volkmann's 1,800-man advance guard. Volkmann with eight companies of the Johann Jellacic Infantry Regiment Nr. 53 managed to evict the Franco-Italians from San Bonifacio. However, Oberst Ignaz Csivich von Rohr and five companies of the Oguliner Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 3 were unable to secure the adjacent village of Villanova and its bridge over the Alpone River. Darkness and a rainstorm brought the action to a close. Historian Digby Smith called casualties from both sides "light" but listed the skirmish as an Austrian victory.[2]

On the same day as the clash at San Bonifacio, Archduke John received news of his brother Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen's defeat at the Battle of Eckmühl.[25] John deployed his army in a "formidable" defensive position blocking the main highway. The army's right flank lay at Soave behind the Alpone while its left stood at Legnago behind the Adige. John posted three battalions north of Soave<[23] to hold Monte-Bastia. The Austrian center stood around San Bonifacio. Most of Eugène's army was deployed north of Arcole, though a few units lined the west bank of the Adige below the confluence of that river with the Alpone. The Franco-Italian left wing stretched north to Illasi and Cazzano di Tramigna. Eugène planned to turn John's right flank, pushing the Austrians toward Venice. Meanwhile, Venice's large garrison would break out to the north. If the plan worked, the Franco-Italians might snare John's entire army between the two forces.[25]

Eugène's army occupied the same ground where the Battle of Caldiero of 1805 was fought. Macdonald's corps held Caldiero in the center while Seras, Abbé, one Italian brigade, and the Italian Guard were on high ground on the left at Colognola ai Colli. Pully's dragoon division was in reserve, while the other cavalry units were deployed on the west bank of the Adige under Grouchy.<[23] On 29 April, General of Brigade Antoine-Louis-Ignace Bonfanti's brigade of Fontanelli's division and the Italian guard attacked the Austrian detachment on the heights. Meanwhile, Grenier led the divisions of Seras and Abbé to attack Soave, with MacDonald's troops in support.[26]

Eugène committed 23,000 men to the fight, including 24 battalions, 10 squadrons, and eight pieces of artillery. The units involved were three battalions of the 1st Italian Line Infantry Regiment and one battalion of the 2nd Italian Line from Bonfanti's brigade, three battalions of the Royal Italian Guard, 4 squadrons each of the 20th and 30th Dragoon Regiments, plus two squadrons of the 8th Hussars. Grenier sent in two guns and four battalions of the 53rd Line from Seras' division, and two battalions each of the 8th Light and 102nd Line Infantry Regiments from Abbé's division. MacDonald committed two guns and five battalions of the 9th, 84th, and 92nd Line from Broussier's division, and four guns and four battalions of the 29th Line from Lamarque's division.[27]

The defenders were 18,000 troops in 21 battalions and 24 guns in four batteries from Albert Gyulai's VIII Armeekorps. General-major Hieronymus Karl Graf von Colloredo-Mansfeld's brigade was made up of three battalions each of Infantry Regiments Strassoldo Nr. 27 and Saint-Julien Nr. 61. General-major Anton Gajoli's brigade consisted of three battalions of Franz Jellacic Infantry Regiment Nr. 62 and two battalions of 1st Banal Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 10. Johann Kalnássy's brigade and other units included three battalions each of Infantry Regiments Reisky Nr. 13, Simbschen Nr. 43, and Johann Jellacic Nr. 53, plus two battalions of Oguliner Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 3.[27]

Led by the Italian Guard, Bonfanti's troops stormed Monte-Bastia[25] and seized Castelcerino. Grenier's attacks on Soave and San Bonifacio were repelled, however. The Franco-Italians suffered 1,000 casualties while the Austrians lost 400 killed and wounded, plus 300 captured. Smith called this action an Austrian victory.[27]

On 30 April, John counterattacked with 11 battalions and recaptured the lost positions.[25] Bonfanti was forced to pull back to Colognola.[26] Smith placed Austrian strength at eight battalions and 6,000 troops, including two battalions of 2nd Banal Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 11 and three battalions each from the two Jellacic Regiments. General of Brigade Jean Joseph Augustin Sorbier led the 5,000 men in seven battalions of Bonfanti's brigade and the Italian Guard. Italian losses numbered 409 killed and wounded while the victorious Austrians lost 300 killed and wounded, plus 572 missing. Smith expressed criticism of Eugène for neither supporting his troops at Castelcerino, nor mounting a holding attack in front. Sorbier, a different officer than Eugène's artillery chief, was mortally wounded[27] and died on 21 May.[28]

Result

John received orders from Archduke Charles on 29 April. He was urged to defend the territory he had captured, but was allowed to use his discretion. John knew that with Napoleon advancing on Vienna, his position in Italy could be flanked by enemy forces coming from the north. He decided to retreat from Italy and defend the borders of Austria in Carinthia and Carniola. After breaking all bridges over the Alpone, John began his withdrawal in the early hours of May 1, covered by Feldmarschallleutnant Johann Maria Philipp Frimont's rear guard.[29]

After being delayed all day repairing an important bridge, Eugène's army began its pursuit on 2 May. The viceroy ordered Durutte to cross the Adige at Legnago with his division and head for Padua on the Brenta. From there he would rendezvous with troops from Venice and escort a supply train to the Piave to rejoin Eugène. Meanwhile, Frimont defeated the light brigade at Montebello Vicentino and got across the Brenta in good order while destroying the bridges.[30] In a series of actions on 2 May, the Austrians lost 200 killed and wounded while inflicting 400 casualties on their pursuers, including Debroc wounded. However, the Franco-Italians rounded up 850 sick or straggling Austrians during the day. Frimont, General-major Franz Marziani, and General-major Ignaz Splényi each led Austrian units in separate actions on the 2nd.[31]

After the rough handling of his light brigade, the viceroy expanded it into a light division and put General of Brigade Joseph Marie, Count Dessaix at its head. He added three additional voltiguer battalions, two more cannons,[30] and the 9th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment. The new division was destined to play a key role in Eugène's victory at the Battle of Piave River on 8 May 1809.[32]

Explanatory notes

- Smith listed three separate actions at San Bonifacio, Soave, and Castelcerino. In each case he called the result an Austrian victory.

- Petre did not describe the battle but named it Caldiero.[3]

Notes

- Bodart 1908, p. 401.

- Smith 1998, pp. 294–295.

- Petre 1976, p. 300.

- Bowden & Tarbox 1980, pp. 101–103.

- Schneid 2002, pp. 181–183.

- Smith 1998, pp. 286–287.

- Schneid 2002, pp. 65–66.

- Schneid 2002, p. 66.

- Rothenberg 1982, p. 139.

- Rothenberg 1982, p. 141.

- Schneid 2002, p. 69.

- Schneid 2002, p. 70.

- Smith 1998, p. 286.

- Schneid 2002, p. 272.

- Epstein 1994, pp. 80–81.

- Schneid 2002, p. 75.

- Epstein 1994, p. 82.

- Schneid 2002, p. 76.

- Epstein 1984, p. 70.

- Epstein 1994, p. 83.

- Smith 1998, p. 293.

- Epstein 1994, pp. 83–84.

- Schneid 2002, p. 78.

- Epstein 1994, p. 84.

- Epstein 1994, p. 86.

- Schneid 2002, p. 79.

- Smith 1998, p. 295.

- Broughton 2021, Sorbier.

- Schneid 2002, pp. 86–87.

- Epstein 1994, p. 87.

- Smith 1998, p. 297.

- Schneid 2002, p. 80.

References

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618-1905). Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- Bowden, Scotty; Tarbox, Charlie (1980). Armies on the Danube 1809. Arlington, Texas: Empire Games Press.

- Broughton, Tony (2021). "Generals Who Served in the French Army during the Period 1789-1815". Archived from the original on 16 May 2021.

- Epstein, Robert M. (1994). Napoleon's Last Victory and the Emergence of Modern War. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0664-5.

- Epstein, Robert M. (1984). Prince Eugene at War: 1809. Arlington, Texas: Empire Games Press. ISBN 0-913037-05-2.

- Petre, F. Loraine (1976) [1909]. Napoleon and the Archduke Charles. New York, NY: Hippocrene Books.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1982). Napoleon's Great Adversaries, The Archduke Charles and the Austrian Army, 1792-1814. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33969-3.

- Schneid, Frederick C. (2002). Napoleon's Italian Campaigns: 1805-1815. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-96875-8.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

Further reading

- Chandler, David G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York, NY: Macmillan.

External links

Media related to Battle of Caldiero (1809) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Caldiero (1809) at Wikimedia Commons