Battle of Hulao

The Battle of Hulao, (Chinese: 虎牢之戰) or Battle of Sishui (汜水之戰, Wade–Giles: Ssŭ Shui),[2] was a decisive Tang victory over the rival Zheng and Hebei-based Xia polities during the transition from Sui to Tang. The battle took place during the Luoyang–Hulao campaign on 28 May 621 when a Xia army – led by Dou Jiande, ruler of Xia – was defeated attacking a smaller Tang army – led by Prince Li Shimin – entrenched at the strategic Hulao Pass.

| Battle of Hulao | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the transition from Sui to Tang | |||||||

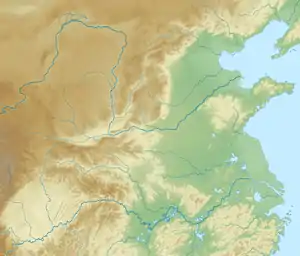

Map of the Luoyang–Hulao campaign | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Tang dynasty | Xia regime | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Li Shimin | Dou Jiande (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Likely under 10,000 | 100,000–120,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3,000 killed ~50,000 taken captive | |||||||

Hulao Pass Location of the battle (Chinese Northern Plain) | |||||||

Li launched the Luoyang–Hulao campaign in August 620, attacking eastwards and quickly besieging Wang Shichong, ruler of Zheng, in Luoyang. Zheng attempts to break the siege failed, and they appealed to Xia for help. In April 621, Dou led a Xia army of 100,000–120,000 troops westward to break the siege. Instead of retreating back to the Tang heartland in Shanxi, Li maintained the siege and took a small part of the Tang army further east to the Hulao Pass to block the Xia. A stalemate ensued for a few weeks; the Tang refused to fight outside of their positions, and the Xia refused to outflank Li or redirect their offensive to Shanxi.

Li broke the stalemate at the end of May by feinting the departure of a large part of the Tang cavalry. On the morning of 28 May, the Xia issued a challenge by arraying for battle in the open. The Tang sapped the endurance and unit cohesion of the waiting Xia by delaying the main action. A Tang cavalry probe at noon developed into a general attack as Xia cohesion collapsed. The Xia retreat, disrupted by poor communications and Tang cavalry in the rear and flanks, turned into a rout. The Xia defeat and Dou's capture led to the surrender of both Zheng and Xia to Tang. Tang emerged with control over the central plains, a dominant position from which it completed conquering China in 628.

Background

During the later reign of the second emperor of the Sui dynasty, Yang (r. 604–618), the dynasty's authority began to wane: the immense material and human cost of the protracted and fruitless attempts to conquer the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo, coupled with natural disasters, caused unrest in the provinces, and military failures eroded the emperor's prestige and legitimacy ('Mandate of Heaven') among the provincial governors.[3][4][5] Yang nevertheless continued to be fixated on the Korean campaigns, and by the time he realized the gravity of the situation, it was too late: as revolts spread, in 616, he abandoned north China and withdrew to Jiangdu, where he remained until his assassination in 618.[5][6][7]

Local governors and magnates rose to claim power in the wake of Yang's withdrawal. Nine major contenders emerged, some claiming the imperial title, others, contenting themselves, for the time being, with the more modest titles of 'Duke' (gōng) and 'King' (wáng).[8] Among the most well-positioned contenders was Li Yuan, Duke of Tang and governor of Taiyuan in the northwest (modern Shanxi). A scion of a noble family related to the Sui dynasty, and with a distinguished career behind him, Li Yuan was an obvious candidate for the throne. His province possessed excellent natural defences, a heavily militarized population and was located near the imperial capitals of Daxingcheng (Chang'an) and Luoyang.[9][10] In autumn 617 Li Yuan and his sons, Li Shimin and Li Jiancheng, led their troops south. In a lightning campaign they defeated the Sui forces that tried to bar their way and, on 9 November, Li Yuan's troops stormed Chang'an.[11] Li Yuan was now firmly placed as a major contender for the imperial throne, and on 16 June 618 he proclaimed himself the first emperor of the Tang dynasty.[10][12]

In a series of campaigns in 618–620 the Tang, led by the talented Li Shimin, managed to eliminate their rivals in the northwest and repel an attack by Liu Wuzhou, who had taken control of Shanxi,[13][14] but they still had to expand their control to the northeastern plain and the modern provinces of Hebei and Henan, which, in the words of historian Howard J. Wechsler, would decide whether the new dynasty "would remain a regional regime or whether they would succeed in uniting the country under its control".[15] By early 620, two major regimes had established themselves over this region. Henan was controlled by the Luoyang-based Wang Shichong, a former Sui general who declared himself the first emperor of the Zheng dynasty after defeating another rebel leader, Li Mi, at the Battle of Yanshi and absorbing his army and territories.[16][17] Hebei was ruled by the one-time bandit leader Dou Jiande, who had risen in revolt against the Sui already in 611. From his base at Mingzhou in south-central Hebei he had expanded his control south towards the Yellow River, claiming the title of 'King of Xia'. Like Wang and the Tang, he too made use of the pre-existing Sui officialdom and administrative apparatus to maintain his realm.[18][19]

In 619, Dou defeated the Tang army under Li Yuan's cousin Li Shentong and captured their territories north of the Yellow River, while from Luoyang Wang was a constant threat to the cities of the lower Yellow River that had only recently acknowledged Tang authority.[20] The two men are presented as diametrically different characters in the sources: while Dou was chivalrous and successfully extended his territories by judicious moderation, Wang's arbitrariness and lack of courtesy quickly alienated many of his own supporters, leading two of his most distinguished generals, Qin Shubao and Luo Shixin, to desert him and join the Tang.[21] The Tang began launching raids against Wang, causing morale to drop and many of his men to defect. Wang was forced to take hostages from the families of his own generals to ensure their loyalty, and impose kin punishment for any trespassing. Although up to 30,000 people ended up as virtual prisoners in his palace city in Luoyang, these acts only served to further undermine his regime.[22]

Li Shimin besieges Wang Shichong at Luoyang

Fresh from his crushing victory over Liu Wuzhou, in August 620 Li Shimin, with an army of 50,000 men, began his advance from Shanxi towards Luoyang.[25] The strategic aim of the Tang prince was to capture the Yellow River valley up to the sea, thus separating the territories held by rival regimes in the north (i.e., Dou Jiande) from any allies in the south, particularly after Du Fuwei, a rebel leader who controlled the Huai River area, chose to acknowledge Tang authority.[26]

Starting from Shenzhou, Li Shimin's progress was swift, advancing against little resistance as Wang feared risking an open confrontation and remained behind the walls of Luoyang. By September, Tang troops had begun to establish a ring of fortified camps around the city.[27][28] Wang's offers of a settlement based on a partition of the empire were rejected by Li Shimin. While both sides skirmished around Luoyang, each trying to protect or prevent the supply convoys coming into the city, Tang detachments had penetrated further south, east and north, triggering the defection of most of central Henan from Wang's control. By the end of the year, only the distant cities of Xiangyang and Xuzhou remained under Wang's control, but were unable to provide any assistance.[29][30] The monks of the nearby Shaolin Monastery[lower-alpha 1] also sided with Li Shimin, defeating a detachment of Wang's army at Mount Huanyuan and capturing his nephew, Wang Renze.[32]

Isolated in his capital and the territory immediately around it, Wang Shichong was growing desperate and more aggressive, launching two major attempts to break out of the Tang blockade in early 621. Both battles were hard fought, but eventually won by the Tang, largely thanks to the intervention of Li Shimin with his bodyguard of 1,000 heavily armed horsemen.[33][lower-alpha 2] The failure of these attempts meant that the siege became ever closer, with siege engines employed to support daily attacks on the city from all sides.[35] The supply situation in Luoyang grew steadily worse as the siege continued into winter and then spring. By March, people were reportedly shifting through dirt to find traces of food, or ate cakes of rice and mud.[30] No one was spared from the suffering, not even the highest officials; and of the 30,000 prisoners held by Wang in his palace, barely a tenth were left alive.[36] Nevertheless, Wang refused any suggestion of surrender, placing his final hopes on an intervention by Dou Jiande, to whom he had sent envoys already in late 620.[30][37]

Dou Jiande marches west and Li Shimin occupies Hulao

During the siege of Luoyang, Dou Jiande and the Tang had been engaged in negotiations, but these had been inconclusive: Dou could not ignore the threat posed by the Tang, but was as yet unwilling to effect a complete breach, and made some conciliatory gestures such as releasing a Tang princess he had captured in 619.[38] When Wang's pleas arrived at his court, Dou was persuaded by his councillor Liu Bin that the situation presented both danger and opportunity: if Luoyang fell, the Tang would next turn against Dou, but if Dou intervened and saved Luoyang, it would be easy to oust the weakened Wang and annex Henan to his own Xia state.[30][39] It was therefore probably by design that Dou waited until April, when Wang's situation had become critical, before he began marching west to relieve the siege of Luoyang.[40]

The Tang launched an attack from their bases in Shanxi against Dou's flank, hoping to divert his attention, but in vain. Dou had enough men to strongly garrison his territory, while still mustering a huge force for marching against Li Shimin.[36] The 10th-century Old Book of Tang and the 11th-century Zizhi Tongjian put Dou's army at 100,000 strong, while the 8th-century works Tongdian and Taizong zun shi (surviving only in fragments), raise it to 120,000 men. Although possibly exaggerated, an army of this size was well within the capabilities of the time. The Xia army was accompanied by a similarly large supply train, comprising both carts and boats.[41][42]

The approach of the Xia army placed the Tang army at Luoyang in a predicament: with no prospects of reinforcements, and with the loyalty of the recently captured cities in Henan suspect, remaining in place to be caught between Wang's men in Luoyang and Dou's army was a recipe for disaster. The older, more experienced and cautious of Li Shimin's generals suggested that he abandon the siege and retire west to Guanzhong, but the Tang prince refused to heed them, as this would mean abandoning the entirety of eastern China to Dou Jiande. Leaving control of the populous northeastern plain to Dou would strengthen his regime, and allow him to expand south to the south, where Du Fuwei and other Tang clients would be forced to submit. Not only would this mean abandoning the unification of the empire, but it would place the Tang regime itself in peril.[41][43] In what his modern biographer C. P. Fitzgerald called "the most critical military decision of his life",[43] Li Shimin opted to confront the Xia army with a part of his forces, while leaving most of his army to maintain the siege of Luoyang. This was a risky gamble, as a defeat would risk eliminating the main Tang army, and opening the path for Dou to capture not only Luoyang, but Shanxi and Chang'an itself.[44]

Leaving the siege of Luoyang in the hands of his younger brother Li Yuanji and the general Qutu Tong, Li Shimin took 3,500 men to the Hulao Pass, some 60 miles (97 km) to the east of Luoyang, which he occupied on 22 April. His force was augmented by the garrison of the local town, but is unlikely to have exceeded 10,000 men, albeit representing some of the best troops in the Tang army.[41][45] The Hulao Pass was formed by the ravine of the Sishui river. Lined on both banks by escarpments and steep hills, rising in the south to the Song mountains, it possessed major strategic importance, as the east–west road along the Yellow River's south bank crossed it.[41][46] Fitzgerald, who visited the area himself in the early 20th century, described this "Chinese Thermopylae"[47] as follows:

The stream flows in a flat valley about a mile broad, bordered to the west by the loess hills which end in a steep slope. To the east the stream has in past ages scoured out a low, vertical cliff, on the top of which the great plain begins; flat, featureless, dotted at intervals with villages in groves of trees. The stream itself, receding from this cliff in the course of time, now flows in the centre of the sunken valley, with a stretch of flat land on either bank. The road from the east to Lo Yang [Luoyang] and Shensi [Shanxi] descends into the ravine, crossing the stream at the little city of Ssŭ Shui [Sishui], before entering the hills by a narrow defile among precipices.

Standoff at Hulao and Dou Jiande's dilemma

When Dou Jiande's army arrived before Hulao, Li Shimin headed a daring raid to raise his own army's morale in the face of such a numerically superior enemy. Taking only 500 horsemen, he crossed the river and advanced towards the Xia camp. Leaving the bulk of this force in ambush, Li Shimin pressed on with only four or five men as escort. When the Xia troops attacked, Li Shimin felled several of them with his precise archery,[lower-alpha 3] keeping them at a distance while leading them on into the ambush he had prepared. The Xia lost over 300 men, and a number of higher officers were taken prisoner.[49]

Li Shimin followed up this success by sending a letter to Dou, addressing him as if he were a subject, and demanding that he abandon the region.[47] Dou responded by attacking the walled town of Sishui, but found it and the western heights behind strongly held by the Tang. Dou then encamped his forces at Banzhu, a plain 10 miles (16 km) east of the pass.[1][41][47] Over the next weeks, he repeatedly marched to Hulao and offered battle. Li Shimin, however, was content to remain in his powerful defensive position from which his numerically inferior force could easily hold the Xia at bay. The Tang prince knew that time worked in his favour, as each day the standoff continued only brought the garrison of Luoyang closer to starvation and surrender, and when this happened he would be able to launch his strike with the entire strength of the Tang army.[41][50] Furthermore, as time passed, the Xia position too deteriorated. The Xia had to laboriously pull their supply barges upstream, while the Tang were conversely aided by the current; and the very size of the Xia army meant that every passing week the costs of maintaining it in the field exhausted the Xia treasury further.[47]

Other passes were available through the hills near Hulao, but they were smaller and equally defensible. Given the size of the Xia army, the only alternatives for Dou would have been to bypass the Tang position entirely, either by crossing the Yellow River to the north, or by venturing further south to the Huanyuan Pass.[51] Indeed, one of Dou's civil officials, Ling Jing, suggested a different strategic approach, namely to avoid any engagement with Li Shimin, cross to the northern bank of the Yellow River and strike at the Tang heartland in Shanxi, thereby both weakening the Tang and forcing them to abandon the siege of Luoyang without the Xia incurring any casualties. The plan was supported by Dou's wife, Lady Cao, but was not adopted due to the vehement opposition of the Xia generals. This was due in large part to the natural disregard of the military professionals towards a suggestion from someone whom they regarded as an "armchair general", but some sources attribute this opposition to the entreaties and bribery of some Xia generals by Wang Shichong's ambassador, who wished to ensure that Dou remained committed to the relief of Luoyang.[52][53]

Military historian David A. Graff opines that logistical concerns played the major role in Dou's decision to stay at Banzhu, as his huge army was utterly dependent on proximity to the Yellow River and its canal network for its supplies.[41][54] In addition, the heterogeneous nature of the Xia army, containing as it did the forces of various rebel leaders Dou had defeated over the past few years, and whose loyalty was doubtful, prevented Dou from dividing his army and sending various detachments on independent missions.[55]

Battle of Hulao Pass

In the event, after a month had passed, the Tang prince decided to force a confrontation. Li Shimin's reasons for this move are unknown; Graff suggests that it is "possible that he believed the morale of Dou's men had deteriorated, and it is very likely that he did not wish to allow the exposed Xia army to withdraw to safety in Hebei after Luoyang had fallen", or that he was frustrated at Luoyang's unexpectedly long resistance. At the same time, Li Shimin was evidently determined to exploit the opportunity offered by the tactical situation to score a crushing victory against Dou, which would result in the rapid absorption of his domains by the Tang.[57][58]

To entice his enemy to accept battle, Li Shimin sent his cavalry to raid Dou's supply lines, and then led a portion of his forces, with 1,000 horses across the Yellow River, giving the appearance that he had detached them to guard against an attack in the direction of Shanxi. During the night, these troops secretly crossed the river again.[41][59] Dou took the bait, and on the early morning hours of 28 May led a large part of his army against Hulao, deploying his troops for battle along the eastern shore of the Sishui river in challenge to the Tang. Per Li Shimin's plan, the Tang troops did not come forth to deploy for battle; instead they remained in their strong defensive positions in the hills, waiting for the Xia army to tire and begin its withdrawal. Then the Tang, according to Graff, "would rush out and fall upon the by now demoralized and disorganized Xia army".[60][61] This conformed to Li Shimin's usual blueprint, which he had already employed to prevail over Liu Wuzhou and the ruler of eastern Gansu, Xue Rengao: the Tang prince let the enemy advance, stretching their supply lines, and chose a suitable, highly defensible position where to confront them; he avoided a direct confrontation, instead launching raids on his opponent's supply lines, awaiting either signs of weakness or the beginning of a retreat; he then launched an all-out attack aiming at a crushing battlefield success, which he rendered decisive by following it up with a "relentless cavalry pursuit", in Graff's words, to exploit it and bring about the collapse of his opponent's entire regime.[62]

In order to draw the Tang out to the open field, where his superior numbers would carry the day, Dou sent 300 of his cavalry to cross the Sishui stream and provoke Li Shimin to attack. Careful to stick to his plan but also exploit the pretext for a delay offered by Dou, the Tang prince sent only 200 of his horsemen. The duel between the two cavalry forces lasted for some time but proved indecisive, until both sides withdrew to their lines.[63] Apart from this and a minor skirmish between a Xia officer and the Tang general Yuchi Gong,[64] the two armies maintained their standoff from about 08:00 until noon, when the Xia troops began to show signs of thirst and weariness, with soldiers sitting down or breaking formation to fetch water. Li Shimin, from a high vantage point, saw this. With the horses from his earlier feint having returned and his cavalry again at full strength, the Tang prince sent 300 horsemen under Yuwen Shiji in a probing attack.[60][64]

When Li Shimin saw that the demoralized and dispersed Xia troops were thrown into confusion from this assault and struggled to put up a cohesive defence, he sent more of his cavalry to turn Dou's left flank from the south. The Tang attack was inadvertently aided by Dou, who was holding a council with his officers at the time. With his army buckling, Dou reacted by ordering the withdrawal of his entire army from the river to the better defensive position offered by the eastern escarpment of the Sishui valley. However, in the spreading confusion, many officers were not able to reach their men in time, while orders issued by the generals often did not arrive in the fighting ranks. Seeing disorder spreading in the Xia army, Li Shimin ordered his army to launch a general attack against the withdrawing Xia, himself spearheading the attack at the head of his remaining cavalry.[60][65] Li Shimin's 18-year-old cousin Li Daoxuan particularly distinguished himself in this stage of the battle, charging through the Xia line until he emerged in their rear, turning round to emerge on the other side, and repeating this feat so many times that at the end of the battle so many arrows stuck out of his armour that the Chinese sources liken his appearance to a porcupine.[60][66]

The ensuing battle was bloody, but was decided when Li Shimin and a part of his cavalry broke through the Xia lines and reached the eastern escarpment, planting the Tang banners in full view of both armies. Possibly coupled with the arrival of the flanking Tang cavalry, this development caused the complete collapse of the Xia army: trapped between the Tang forces and the eastern cliffs, 3,000 Xia soldiers fell in the field or the subsequent pursuit, but more than 50,000 were taken prisoner, and the rest dispersed in the surrounding countryside. These included Dou Jiande himself, who was wounded, unhorsed and captured while trying to find a way to cross the Yellow River.[67][68] The rout of the Xia state was complete: only a few hundreds of horsemen reached the Xia capital, and with their ruler captured, any possibility of rallying the remaining Xia forces was gone.[69]

Aftermath and impact

The Tang victory at Hulao spelled the end for Luoyang too: bereft of any hope of rescue, Wang Shichong surrendered on 4 June, after Li Shimin displayed the captured Dou Jiande and his generals before the city walls.[62][70] Li Shimin returned to Chang'an, which he entered at the head of a triumphal procession, wearing golden armour, followed by the two captive rivals and their courts, 25 of his own generals, and 10,000 horsemen.[71] Dou's wife and senior officials managed to escape the Xia camp and reach the safety of Hebei, but although some wanted to continue fighting under Dou's adopted son, most, including the influential Qi Shanxing, regarded the outcome of the battle as a sign that the Tang possessed the 'Mandate of Heaven', the divine right to rule. On 10 June, the Xia formally surrendered to the Tang, with Dou's ally Xu Yuanlang and Wang Shichong's brother Shibian following suit over the next days.[62][72] In stark contrast to the leniency with which the Tang treated most of their defeated rivals, Dou Jiande and Wang Shichong were soon eliminated: Dou was sent to Chang'an, where he was executed, while Wang was ostensibly allowed to retire in exile in Sichuan, but was killed on his way there.[70]

According to David Graff, the battle at Hulao was "the single most decisive engagement of the civil wars" that followed the fall of Sui,[56] while C. P. Fitzgerald considers it "one of the decisive battles in the history of the world".[71] By defeating Dou Jiande and Wang Shichong, the Tang eliminated their two strongest rivals and brought the vital north-eastern plain under their control, securing an unchallenged ascendancy over all other competing factions and making possible the reunification of China under Tang rule.[56][70][71] Tang authority had not yet encompassed all of China and rebellions occurred for a few more years. The most notable of these occurred in late 621, when the former Xia officials in Hebei rose up in reaction to the execution of Dou Jiande, under the leadership of Dou's cavalry commander Liu Heita. Nevertheless, the course the civil war had been decided at Hulao, and the various rebel leaders were overcome one by one; the last, Liang Shidu of Shuofang, was defeated in June 628, marking the end of the civil war.[73][74]

In late 629, Li Shimin, by now Emperor of China, ordered the erection of Buddhist monasteries on the sites of seven of the battles he had fought during the civil war. In a gesture that illustrated the emperor's desire to heal the divisions of the conflict, for Hulao he chose the name "Temple of Equality in Commiseration".[75]

Footnotes

- Buddhism prohibits violence and does not condone warfare, but there are several recorded cases of Buddhist monks participating in combat during rebellions in early medieval China, particularly in the chaos that followed the Sui collapse. The fact that the Shaolin monks fought in support of the Tang is known mainly from engraved steles marking the property rights granted to them in the aftermath of the Tang victory for their support. Their existence helped preserve the monastery from the anti-Buddhist purges of later Tang rulers.[31]

- Like most of the contemporary Chinese military leaders, who were expected to prove their personal bravery on the battlefield and motivate their men by their example, rather than stay in the rear and co-ordinate their army, Li Shimin always led from the front—accompanied by an elite force of 1,000 black-clad, black-armoured horsemen.[34]

- Li Shimin was accounted "the most famous archer of his age" according to Fitzgerald, a skill that would help preserve his life on numerous occasions.[48]

References

- Graff 2000, p. 83.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 70.

- Wright 1979, pp. 143–147.

- Graff 2002, pp. 145–153.

- Wechsler 1979, pp. 152–153.

- Wright 1979, pp. 147–148.

- Graff 2002, pp. 153–155.

- Graff 2002, pp. 162–165.

- Wechsler 1979, pp. 150–154.

- Graff 2002, p. 165.

- Wechsler 1979, pp. 154–160.

- Wechsler 1979, p. 160.

- Wechsler 1979, p. 163.

- Graff 2002, pp. 169–170.

- Wechsler 1979, pp. 163, 165.

- Graff 2002, pp. 163, 165–168.

- Wechsler 1979, pp. 165–166.

- Graff 2002, pp. 162–163, 165–168.

- Wechsler 1979, pp. 166–167.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 70–71.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 72.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 72–73.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 77 & Plate II.

- Yang 2006, p. 171.

- Graff 2002, p. 170.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 68, 73.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 73.

- Graff 2002, pp. 170–171.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 73–74.

- Graff 2002, p. 171.

- Shahar 2008, pp. 20–22.

- Shahar 2008, pp. 23–24.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 76–77.

- Graff 2002, pp. 175–176.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 77–78.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 78.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 76, 78.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 74.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 76.

- Graff 2002, pp. 171–172.

- Graff 2002, p. 172.

- Graff 2000, pp. 85–86.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 79.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 80.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 80–81.

- Graff 2000, p. 82.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 83.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 14.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 82–83.

- Graff 2000, pp. 83–84, 94–95.

- Graff 2000, pp. 82–83.

- Graff 2000, pp. 84–85.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 83–84.

- Graff 2000, pp. 84–88.

- Graff 2000, pp. 88–89.

- Graff 2002, p. 176.

- Graff 2000, pp. 95–96.

- Graff 2002, pp. 172–173.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 84–85.

- Graff 2002, p. 173.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 85.

- Graff 2002, p. 174.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 85–86.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 86.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 86–87.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 87.

- Graff 2002, pp. 173–174.

- Fitzgerald 1933, pp. 87–88.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 88.

- Wechsler 1979, p. 167.

- Fitzgerald 1933, p. 89.

- Graff 2000, p. 96.

- Graff 2002, pp. 177–178.

- Wechsler 1979, pp. 167–168.

- Graff 2002, p. 185.

Sources

- Fitzgerald, C. P. (1933). Son of Heaven: A Biography of Li Shih-Min, Founder of the T'ang Dynasty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-49508-1. OCLC 811586302.

- Graff, David A. (2000). "Dou Jiande's Dilemma: Logistics, Strategy, and State Formation in Seventh-Century China". In van de Ven, Hans (ed.). Warfare in Chinese History. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. pp. 77–105. ISBN 978-90-04-11774-7.

- Graff, David A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300–900. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23955-4.

- Shahar, Meir (2008). The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3110-3.

- Wechsler, Howard J. (1979). "The Founding of the T'ang Dynasty: Kao-tsu (Reign 618–26)". In Twitchett, Dennis (ed.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906 AD, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–187. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Wright, Arthur F. (1979). "The Sui Dynasty (581–617)". In Twitchett, Dennis (ed.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906 AD, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 48–149. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Yang, Hong (2006). "From the Han to the Qing". In Howard, Angela Falco; Li, Song; Wu, Hung; Yang, Hong (eds.). Chinese Sculpture. New Haven and Beijing: Yale University Press. pp. 105–197. ISBN 978-0-300-10065-5.