Battle of the Imjin River

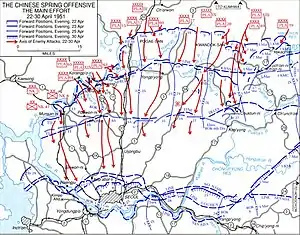

The Battle of the Imjin River (Filipino: Labanan sa Ilog Imjin), also known as the Battle of Solma-ri (Korean: 설마리 전투) or Battle of Gloster Hill (글로스터 고지 전투) in South Korea, or as Battle of Xuemali (Chinese: 雪马里战斗; pinyin: Xuě Mǎ Lǐ Zhàn Dòu) in China, took place 22–25 April 1951 during the Korean War. Troops from the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) attacked United Nations Command (UN) positions on the lower Imjin River in an attempt to achieve a breakthrough and recapture the South Korean capital Seoul. The attack was part of the Chinese Spring Offensive, the aim of which was to regain the initiative on the battlefield after a series of successful UN counter-offensives in January–March 1951 had allowed UN forces to establish themselves beyond the 38th Parallel at the Kansas Line.

| Battle of the Imjin River | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Chinese Spring Offensive in the Korean War | |||||||

.jpg.webp) Centurion tanks of the 8th Hussars disabled during the retreat of 29th Brigade on 25 April | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| 15,000+ (estimated)[10] | ||||||

Location within South Korea | |||||||

The section of the UN line where the battle took place was defended primarily by British forces of the 29th Infantry Brigade, consisting of three British and one Belgian infantry battalions (Belgian United Nations Command) supported by tanks and artillery. Despite facing a greatly numerically superior enemy, the brigade held its general positions for three days. When the units of the 29th Infantry Brigade were ultimately forced to fall back, their actions in the Battle of the Imjin River together with those of other UN forces, for example in the Battle of Kapyong, had blunted the impetus of the PVA offensive and allowed UN forces to retreat to prepared defensive positions north of Seoul, where the PVA were halted. It is often known as the "Battle that saved Seoul."[11][12]

"Though minor in scale, the battle's ferocity caught the imagination of the world",[13] especially the fate of the 1st Battalion, The Gloucestershire Regiment, which was outnumbered and eventually surrounded by Chinese forces on Hill 235, a feature that became known as Gloster Hill. The stand of the Gloucestershire battalion, together with other actions of the 29th Brigade in the Battle of the Imjin River, has become an important part of British military history and tradition.[14][15]

Background

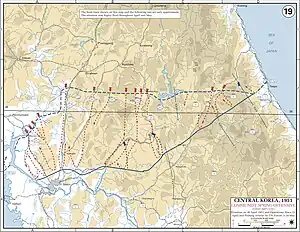

Following the Soviet-backed North Korean invasion of South Korea on 25 June 1950, a UN counter-offensive had reached the North Korean border with China. On the premise of fearing for its own security, China committed troops it had already moved to the border and began three offensives between 3 November 1950 and 24 January 1951 which pushed the UN forces south of the original border between North and South Korea along the 38th Parallel and captured Seoul. A fourth offensive in mid-February was blunted by UN forces in the Battle of Chipyong-ni and Third Battle of Wonju. At the end of February the UN launched a series of offensive operations, recapturing Seoul on 15 March and pushing the front line back northwards. In early April Operation Rugged established the front in a line that followed the lower Imjin river, then eastwards to the Hwacheon Reservoir and on to the Yangyang area on the east coast, known as the Kansas Line. The subsequent Operation Dauntless pushed out a salient between the Imjin river as it dog-legged north and the Hwacheon Reservoir, known as the Utah Line.[16]

UN Forces

On 22 April the front line in the west along Lines Kansas and Utah was held by the United States Army (US) I Corps comprising, from west to east, the South Korean Republic of Korea Army (ROK) 1st Division, the US 3rd Division with the attached British 29th Brigade, the US 25th Division with the attached Turkish Brigade and the US 24th Division.[17][18] The 29th Infantry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Tom Brodie, consisted of the 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment (Glosters), under Lieutenant-Colonel James P. Carne; the 1st Battalion Royal Northumberland Fusiliers (Fusiliers), under Lieutenant-Colonel Kingsley Foster; the 1st Battalion Royal Ulster Rifles (Rifles), under the temporary command of Major Gerald Rickord; and the Belgian Battalion, under Lieutenant-Colonel Albert Crahay (700 men), to which Luxembourg's contribution to the UN forces was attached.[19] The brigade was supported by the 25 pounders of 45 Field Regiment Royal Artillery (RA) commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel MT Young, the 4.2 inch mortars of 170 Independent Mortar Battery RA, the Centurion tanks of C Squadron 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars under the command of Major Henry Huth, and by 55 Squadron Royal Engineers.[20][21]

The four battalions of 29th Brigade covered a front of 12 miles (19 km).[22] Gaps between units had to be accepted because there was no possibility of forming a continuous line with the forces available. "Brigadier Brodie determined to deploy his men in separate unit positions, centred upon key hill features"[21] On the left flank, the Glosters were guarding a ford over the Imjin 1 mile (1.6 km) east of the ROK 1st Division; the Fusiliers were deployed near the centre, around 2 miles (3.2 km) northeast of the Glosters; the Belgians, occupying a feature called Hill 194 on the right, were the only element of the 29th Brigade north of the river. Their connection with the rest of the brigade depended on two pontoon bridges about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) apart. These bridges connected the Belgians with Route 11, the 29th Brigade's main line of supply and communication. The Rifles served as the brigade's reserve and were deployed along Route 11.[21][22][23] Extensive defensive preparations were not completed because the British expected to hold the position for only a short time. Neither minefields, deeply dug shelters nor extensive wire obstacles had been constructed. The British position on the Imjin river "was deemed safe" but vulnerable in case of an attack.[24]

Chinese forces

The commander-in-chief of the PVA and North Korean Korean People's Army (KPA) forces in the Field, Marshal Peng Dehuai, planned to "wipe out...the American 3rd Division...the British 29th Brigade and the 1st Division of the Republic of Korean Army...after this we can wipe out the American 24th Division and 25th Division", and promised the capture of Seoul as a May Day gift to Mao Zedong. To achieve the objective Peng planned to converge on Seoul with three PVA army groups and a KPA corps; a total strength of some 305,000 men.[25][26] The III and IX Army Groups were to attack the right flank of the US 3rd Division and the 24th and 25th Divisions on the Utah Line, east of the Imjin where it turned north. The XIX Army Group on the PVA right flank, west of the Imjin river where it turned north, were to attack the remainder of the 3rd Division and the ROK 1st Division. On the XIX Army Group front, the KPA I Corps and PVA 64th Army would attack the ROK 1st Division, while the 63rd Army would attack on their left, pitting it against 29th Brigade. The 63rd Army comprised three divisions, the 187th, 188th and 189th, with each division comprising three regiments, each of which comprised three battalions. Some 27,000 men in 27 battalions would be attacking 29th Brigade's four battalions, albeit in echelon, one division after the other.[25][27]

Battle

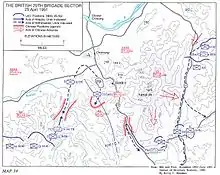

The first night

The battle opened on the night of 22 April 1951. A PVA patrol on the north bank of the river moved around the Belgians on Hill 194 and continued to advance east towards the two bridges on which the Belgians depended.[28] Elements of the 29th Brigade's reserve, the 1st RUR, were deployed forward at about 22:00 to secure the crossing but were soon engaged by PVA forces trying to cross the river. The Royal Ulster Rifles were unable to secure the bridges.[29] This development meant that the Belgian battalion on the north bank of the river was in danger of being isolated from the rest of the 29th Brigade.

PVA forces following the initial patrol either attacked the Belgian positions on Hill 194 or continued their advance towards the bridges. Those who were able to cross the Imjin attacked the Fusiliers' right rear company, Z Company, on Hill 257, a position close to the river and almost directly south of the crossings.[30] Further downstream, PVA forces managed to ford the Imjin and attacked the Fusiliers' left forward company, X Company, on Hill 152. The retreat of X Company from Hill 152 had serious consequences for Y Company, which occupied the right forward position of what can be described as a squarish fusilier position marked out by four widely spaced company perimeters at the corners.[30] Although Y Company was not attacked directly, PVA forces threatened its flanks by forcing Z and X Companies from their positions. After unsuccessful British attempts to regain those lost positions on Hill 257 and 194, Y Company's position was abandoned, the retreat being covered by C Squadron, 8th Hussars.[29][31]

On the left of the brigade's line, a patrol of 17 men from the Glosters' C Company lying in wait on the river bank repulsed three attempts by a battalion of the 559th Regiment, 187th Division to cross the river, eventually retiring without loss when their ammunition ran low and assaulting troops finally gained the opposite bank.[32][33] During the night the Glosters' A and D Companies were attacked, and by 07:30 A Company, outnumbered six to one, had been forced from its position on Castle Hill. An attempt to retake it failed, during which Lieutenant Philip Curtis single-handedly destroyed a PVA machine-gun position with a grenade but was himself killed by a burst of machine-gun fire in the process. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.[34][35]

The Glosters' withdrawal to Hill 235

On 23 April, attempts by the Fusiliers and forces from the US 3rd Infantry Division's reserve to regain control of areas lost during the night failed. An attack by the US 1st Battalion, 7th Infantry, on enemy forces near Hill 257 was ordered to support the Belgian withdrawal from the north bank of the Imjin River. Despite losing seven vehicles, the Belgian Battalion successfully withdrew to the east and took up new positions south of the Glosters and the Fusiliers before moving to the vicinity of the 29th Brigade's command post.[36][37][38]

At around 20:30 on 23 April, the Glosters' A Company, now at less than half strength and with all officers killed or wounded, fell back to Hill 235. The withdrawal left D Company's position exposed, and with one of its platoons badly mauled in the overnight fighting, it too withdrew to the hill.[39] B Company had not been pressed during the night, but the withdrawal of D Company on their left and the Fusiliers on their right left them exposed, and they were withdrawn to Hill 316, 800 yards (730 m) east of C Company.[40][41]

During the night of 23/24 April, the Glosters' B Company, outnumbered 18:1, endured six assaults, calling in artillery on their own position to break up the last of them. Low on ammunition and having taken many casualties, the seventh assault at 08:10 forced them to abandon their position, and just 20 survivors made it to Hill 235, to which battalion HQ, the Support Company and C Company had already withdrawn.[42][lower-alpha 1] As B Company fought for its life, the PVA 188th Division crossed the Imjin and attacked the Fusiliers and the Royal Ulster Rifles on the right of the brigade's line. The 187th Division also engaged the brigade's battalions on the right, while the 189th Division kept up the pressure on the left.[36]

Most dangerous for the integrity of the 29th Brigade was the deep penetration of the line between the Glosters and the Fusiliers which had cut off the former. To counter the PVA attack and protect the Glosters from being completely surrounded, the Philippine 10th Battalion Combat Team (BCT) was temporarily attached to the 29th Brigade. A combined force of M24 tanks of the 10th BCT and Centurions of the 8th Hussars supported by infantry reached a point 2,000 yards (1,800 m) from Hill 235 on 24 April. However, the column failed to make contact as the lead tank was hit by PVA fire and knocked out, blocking the route and making any further advance against heavy resistance impossible. At this point, according to an official American narrative of operations, "the brigade commander considered it unwise to continue the effort to relieve the Gloucester Battalion and withdrew the relief force".[44][38]

Retreat of the 29th Brigade

Continued PVA pressure on the UN forces along the Imjin prevented a planned attack by the US 1st and 3rd Battalions, 65th Infantry, to relieve the Glosters. When two further attempts by a tank troop to link up with the Glosters failed, Brodie left the decision to Carne whether to attempt a break-out or surrender. No further attempts to relieve the Glosters were undertaken because, at 08:00 on 25 April, US I Corps issued the order to execute Plan Golden A, which called for a withdrawal of all forces to a new defensive position further south.[45][46]

In accordance with orders issued by I Corps, the Fusiliers, Rifles and Belgians, supported by the tanks of the 8th Hussars and the Royal Engineers of 55 Squadron, withdrew to the safety of the next UN position. The Belgians occupied blocking positions west and southwest of the 29th Brigade's command post in order to allow the other units of the brigade to fall back through the battalion's positions.[46] The withdrawal under intense enemy pressure was made even more difficult by the fact that PVA forces dominated parts of the high ground along the line of retreat; they were able not only to observe any movements by the 29th Brigade, but also to inflict heavy casualties on the retreating units. Among those killed was the commanding officer of the Fusiliers, Lieutenant-Colonel Foster, who died when his jeep was hit by PVA mortar fire. In the words of Major Henry Huth of the 8th Hussars, the retreat was "one long bloody ambush".[47] When B Company of the Ulsters, which had acted as rearguard during the retreat, reached the safety of the next UN line, all elements of the 29th Brigade except for the Glosters had completed the withdrawal.[48][49][46]

The Glosters on Hill 235

The Glosters' situation on Hill 235 made it impossible for them to join the rest of the 29th Brigade after it had received the order to retreat. Even before the failed attempts to relieve the battalion on 24 April, B and C Companies had already suffered such heavy casualties that they were merged to form one company. Attempts to supply the battalion by air drop were unsuccessful.[50] Despite their difficult situation, the Glosters held their positions on Hill 235 throughout 24 April and the night of 24/25 April. In the morning of 25 April, 45 Field Regiment could no longer provide artillery support. Since Brodie had left the final decision to Carne, the Glosters' CO "gave the order to his company commanders to make for the British lines as best as they could" on the morning of 25 April.[45] Only the remains of D Company, under the command of Major Mike Harvey, reached the UN lines after several days. The rest of the battalion surrendered and 459 of them were taken prisoner, including Carne.[51]

Aftermath

Importance of the battle

Had the PVA achieved a breakthrough in the initial stages of their assault, they would have been able to outflank the ROK 1st Division to the west and the US 3rd Infantry Division to the east of the 29th Brigade. Such a development would have threatened the stability of the UN line and increased the likelihood of success for a PVA advance on Seoul. Although the PVA benefited from the brigade's scattered deployment and lack of defensive preparations, they were nevertheless unable to take the positions before UN forces could check further advances. In three days of fighting, the determined resistance of the 29th Brigade severely disrupted the PVA offensive, causing it to lose momentum, and allowed UN forces in the area to withdraw to the No-Name Line, a defensive position north of Seoul, where the PVA/KPA were halted.[52][53][54]

The scope and the outcome of the Imjin River engagement have been subjected to several interpretations according to different historiography traditions. According to official Chinese history, the elimination of the 1st Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment by the Chinese 63rd Army is considered to be an important victory, although the failure of the 64th and the 65th Army to eliminate the entire British 29th Independent Infantry Brigade and capture Seoul due to the defense of ROK 1st Infantry Division was a serious setback. On the other hand, the South Korean contributions to the Imjin River battle are only recorded in sparse detail by the official South Korean history, but historian Allan R. Millet has argued that the ROK 1st Infantry Division's performance in battle demonstrated the potential of South Korean armed forces, in the wake of serious failures during the period of 1950–51. In British Empire countries, the engagement has been interpreted as the 29th Brigade's sacrifice, against impossible odds when facing the Chinese 63rd Army, which ultimately prevented the Chinese from capturing Seoul. Regardless of the interpretations, independent research from historians Zhang Shu Guang and Andrew Salmon concluded that the actions of the 29th Brigade had disrupted the Chinese advance sufficiently to affect the outcome of the First Chinese Spring Offensive.[55][56][57][58][59]

Casualties

According to a memorandum presented to the British cabinet on 26 June 1951, 29th Brigade suffered 1,091 casualties, including 34 officers and 808 other ranks missing.[60] These casualties represented 20[61] to 25 per cent[62] of the brigade's strength on the eve of battle. Of the 1,091 soldiers killed, wounded or missing, 620 were from the Gloucestershire Regiment, which could muster only 217 men on 27 April.[63][64][lower-alpha 2] 522 soldiers of the Gloucestershire Regiment became prisoners of war.[63][lower-alpha 3] Of those taken prisoner, 180 were wounded and a further 34 died while in captivity.[65][66] 59 soldiers of the Gloucestershire Regiment were killed in action.[65] Based on estimates, PVA casualties in the Battle of the Imjin River can be put at around 10,000.[67] As a result of the casualties suffered during the battle, the PVA 63rd Army, which had begun the offensive with three divisions and approximately 27,000 men, had lost over a third of its strength and was pulled out of the front line.[63]

Memorial

The Gloucester Valley Battle Monument was later built at Gloster Hill 37.944198°N 126.936035°E, beside the Seolmacheon stream.

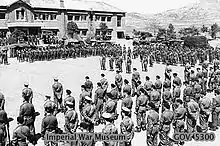

The British Embassy in Seoul organises a service, officially called the Gloster Valley Memorial Service, for veterans on every anniversary of the battle. In 2008, it took place on 19 April as part of formal commemoration ceremonies that were held during 14–20 April.[68] The outline of the commemorations in 2008[68] encompassed a service of commemoration, including the laying of wreaths and the presentations of Gloster Valley Scholarships – financial assistance to deserving children in the area where the battle took place – as well as a picnic lunch that offered visitors the opportunity to mingle with veterans. About 70 British veterans and the British ambassador to South Korea took part in the event.[68]

Individual awards

In the Battle of the Imjin River two Victoria Crosses and one George Cross were awarded to soldiers of the Gloucestershire Regiment:

- Lieutenant colonel James P. Carne, who commanded the battalion, was awarded the Victoria Cross. He was also awarded the US Army's Distinguished Service Cross.[69]

- Lieutenant Philip Curtis, who had recently learnt of his wife's death and who died in a lone counter-attack on enemy machine-guns, was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

- Lieutenant Terence Edward Waters, who died in captivity, was awarded a posthumous George Cross for his conduct shortly after capture.

In addition, several soldiers were awarded the Distinguished Service Order:

- Captain Anthony Farrar-Hockley, 1st Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment[70]

- Major Edgar Denis Harding 1st Battalion, Gloucestshire Regiment OC B Coy

- Major Henry Huth, Officer Commanding, C Squadron, 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars[47]

- Major John Winn, Officer Commanding, Z Company, Royal Northumberland Fusiliers[31]

The Military Cross was awarded to:

- Harvey, 1st Battalion, the Gloucestershire Regiment, for his leadership of a group of 5 officers and 41 men of D Company who escaped and evaded the Chinese encirclement.

- Major Leith-MacGregor DFC, Officer Commanding, Y Company, Royal Northumberland Fusiliers

- Captain Peter Ormrod, 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars[71]

- Lieutenant Guy Temple, for his actions when a platoon from C Company, 1st Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment stopped four attempts by Chinese Communist Forces to cross the river on 22 April, only withdrawing when the platoon ran short of ammunition.

- Captain Charles Stanfield Rutherford Dain, 45, Field Rgt, Royal Artillery, for manning a forward observer post for 2 days and nights whilst wounded.

The Military Medal was awarded to:

- Warrant Officer Class 2 G E Askew, C Troop 170 Independent Mortar Battery

Lieutenant-Colonel Crahay received the U.S. Army's Distinguished Service Cross for his leadership of the Belgian battalion during the battle.[72]

Unit citations

Three units were awarded the US Presidential Unit Citation for their part in the Battle of the Imjin River:

- 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment

- C Troop, 170 Independent Mortar Battery, Royal Artillery

- Belgian battalion

On 8 May 1951, by the command of U.S. President Harry S. Truman, General James Van Fleet presented the President's Distinguished Unit Citation to the Glosters, together with C Troop, 170 Heavy Mortar Battery, which had given invaluable support throughout the battle. The citation says:

HEADQUARTERS

EIGHTH UNITED STATES ARMY KOREA (EUSAK)

Office of the Commanding General

KPO 301

GENERAL ORDERS

NUMBER 286 8 May 1951

BATTLE HONOURS – CITATION OF UNITSBATTLE HONOURS – By direction of the President, under the provisions of Executive Order 9396 (Sec 1, WD Bul. 22.1943), superseding Executive Order 9075 (Sec.III, WD Bul.II, 1942) and pursuant in authority in AR 260-15, the following units are cited as public evidence of deserved honor and distinction. The citation reads as follows:

The 1ST BATTALION GLOUCESTERSHIRE REGIMENT, BRITISH ARMY and TROOP C, 170TH INDEPENDENT MORTAR BATTERY, ROYAL ARTILLERY, attached, are cited for exceptionally outstanding performance of duty and extraordinary heroism in action against the armed enemy near Solma-ri, Korea on 23, 24 and 25 April 1951. The 1st BATTALION and TROOP C were defending a very critical sector of the battle front during a determined attack by the enemy. The defending units were overwhelmingly outnumbered. The 83rd Chinese Communist Army drove the full force of its savage assault at the positions held by the 1st BATTALION, GLOUCESTERSHIRE REGIMENT and attached unit. The route of supply ran Southeast from the battalion between two hills. The hills dominated the surrounding terrain northwest to the Imjin River. Enemy pressure built up on the battalion front during the day 23 April. On 24 April the weight of the attack had driven the right flank of the battalion back. The pressure grew heavier and heavier and the battalion and attached unit were forced into a perimeter defence on Hill 235. During the night, heavy enemy forces had by-passed the staunch defenders and closed all avenues of escape. The courageous soldiers of the battalion and attached unit were holding the critical route selected by the enemy for one column of the general offensive designed to encircle and destroy 1st Corps . These gallant soldiers would not retreat. As they were compressed tighter and tighter in their perimeter defence, they called for close-in air strikes to assist in holding firm. Completely surrounded by tremendous numbers, these indomitable, resolute, and tenacious soldiers fought back with unsurpassed fortitude and courage. As ammunition ran low and the advancing hordes moved closer and closer, these splendid soldiers fought back viciously to prevent the enemy from overrunning the position and moving rapidly to the south. Their heroic stand provided the critically needed time to regroup other 1st Corps units and block the southern advance of the enemy. Time and again efforts were made to reach the battalion, but the enemy strength blocked each effort. Without thought of defeat or surrender, this heroic force demonstrated superb battlefield courage and discipline. Every yard of ground they surrendered was covered with enemy dead until the last gallant soldier of the fighting battalion was over-powered by the final surge of the enemy masses. The 1st BATTALION, GLOUCESTERSHIRE REGIMENT and TROOP C, 170th INDEPENDENT MORTAR BATTERY displayed such gallantry, determination, and esprit de corps in accomplishing their mission under extremely difficult and hazardous conditions as to set them apart and above other units participating in the same battle. Their sustained brilliance in battle, their resoluteness, and extraordinary heroism are in keeping with the finest traditions of the renowned military forces of the British Commonwealth, and reflect unsurpassed credit on these courageous soldiers and their homeland.

BY COMMAND OF LIEUTENANT GENERAL VAN FLEET.

OFFICIAL

LEVEN C ALLEN

Major General US Army.

Chief of Staff.

L. W. STANLEY.

Colonel AGC.

Adjutant General.[73]

The Belgian United Nations Command, which was attached to the British 29th Brigade and replaced the 900 men of the Royal Ulster Rifles on 20 April 1951, initially held the brigade's right flank on the north bank of the river. It also included a Luxembourg platoon. It fought the Chinese there and then conducted a fighting withdrawal, supported by U.S. forces, before taking position in the center of the brigade's line, ahead of brigade headquarters, for the attempts to relieve the Glosters. The Belgian battalion was awarded the United States Distinguished Unit Citation and the Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation for their conduct during the battle.[74]

The Belgian battalion with the Luxembourg detachment of the UN Forces in Korea is mentioned for exceptional execution of its missions and for its remarkable heroism in its actions against the enemy on the Imjin, near Hantangang, Korea during the period from 20 till 26 April 1951. The Belgian battalion with the Luxembourg detachment, one of the smallest units of the UNO in Korea, has inflicted thirty-fold losses on the enemy compared to its own, due to its aggressive and courageous actions against the Communist Chinese. During this period considerable enemy forces, supported by fire by machine guns, mortars and artillery, repeatedly and heavily attacked the positions held by the battalion but, Belgians and Luxembourgers have continuously and bravely repulsed these fanatic attacks by inflicting heavy losses to the enemy forces... The extraordinary courage shown by the members of this units during this period has bestowed extraordinary honor on their country and on themselves

References

Notes

- Accounts of C Company's action at Hill 316 during the night of 23/24 April are contradictory. Battalion adjutant Major Farrar-Hockley, B Company commander Major Harding and Private David Green, who fought with C Company, all state in their books that the company was subject to a strong attack and ordered to withdraw during the night, and Daniel states that only a third of the company reached Hill 235. Lieutenant Temple and Private Coombes, both of C Company, state that the company was not subject to any major attack, and Lieutenant Temple states that, in the absence of the company commander who went missing sometime during the night, he ordered the company to withdraw after daybreak on his own initiative.[43]

- The British embassy's account of the battle states that only 67 officers and other ranks remained with the regiment after battle.[65]

- The British embassy's account of the battle states that 526 soldiers were taken prisoner, not 522.[65]

Citations

- Villahermosa 2009, p. 125.

- Belgians Can Do Too! The Belgian-Luxembourg Battalion in the Korean War, Brussels: Museum of the Army and of Military History, 2010, p. 42, ISBN 978-2-87051-050-6

- Villahermosa 2009, p. 104.

- Paik 1992, p. 138.

- Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 375

- Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, pp. 312–13

- Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 613.

- Salmon 2009, p. 129.

- Salmon 2009, p. 262.

- Millett 2010, pp. 434, 441, Excerpt reads: "Despite [a low estimate of] 30,000 casualties, most of them in the 19th Army Group on the approaches to Seoul, Peng Dehuai could not call off the ill considered offensive that he had never believed would be successful.".

- "Battle of the Imjin River | National Army Museum".

- "The British Regiment that Saved South Korea".

- "Battle of the Imjin", Gloster valley, Seoul: Office of the Defence Attaché, British Embassy, archived from the original on 20 January 2009, retrieved 2 April 2008.

- Hastings 1987, p. 250: "just once, the British played a part which captured the imagination of the Western world."

- Fehrenbach 2001, p. 304.

- Salmon 2010, pp. 15, 43, 46, 53–59, 68–69, 109–110, 113, 127–128.

- Mossman 1990, p. 354 Map 29.

- Hastings 1987, p. 250.

- Salmon 2010, p. 118.

- Farrar-Hockley 1996, pp. 324 & 326.

- Hastings 1987, p. 251.

- Farrar-Hockley 1996, p. 324.

- Mossman 1990, pp. 385–86.

- Hastings 1987, p. 253.

- Mossman 1990, p. 379.

- Salmon 2010, p. 1289.

- Salmon 2010, p. 129.

- Mossman 1990, pp. 386–87.

- Farrar-Hockley 1996, p. 326.

- Mossman 1990, p. 387.

- Hastings 1987, p. 256.

- Mossman 1990, p. 388.

- Salmon 2010, pp. 1–6 Mossman reports four attempts to cross the river were repulsed, but the patrol leader, Lieutenant Temple, claims only three. There are different reports of casualty figures amongst the PVA during the ambush; Salmon, p306, suggests at least a company, possibly a battalion. Lt. Temple estimated 70 in the first engagement alone which, because he initially forgot he had artillery support, was conducted with small arms only (subsequent attempts were also subject to artillery fire from 45 Field Regiment RA, called in by Lt. Temple). This figure is reflected in Mossman's account. It's also worth noting that Lt. Temple's orders were to snatch a prisoner and withdraw if he encountered more than 30 enemy, something else that he forgot.

- Salmon 2010, pp. 151–155.

- Hastings 1987, pp. 256–57.

- Farrar-Hockley 1996, p. 327.

- Hastings 1987, p. 258.

- 3d Infantry Division 1951, p. 2.

- Salmon 2010, pp. 155–157.

- Salmon 2010, pp. 166 & 168.

- Hastings 1987, p. 259.

- Salmon 2010, pp. 176–184.

- Salmon 2010, p. 180.

- Hastings 1987, p. 260.

- Hastings 1987, p. 268.

- 3d Infantry Division 1951, p. 3.

- Hastings 1987, p. 264.

- Farrar-Hockley 1996, pp. 327–28.

- Hastings 1987, pp. 263–67.

- Battle of the Imjin River, UK: Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, archived from the original on 13 May 2008.

- Hastings 1987, pp. 259, 267–69.

- Catchpole 2000, pp. 133–134.

- Farrar-Hockley 1995, pp. 152–153.

- Harding 2011.

- Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, pp. 317–18.

- Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. xii.

- Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 136.

- Salmon 2009, p. 317.

- Zhang 1995, pp. 149–50.

- Memorandum to the British Cabinet, Catalogue reference CAB 21/1985 (26 June 1950). Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- Farrar-Hockley 1996, p. 328.

- Hastings 1987, p. 270.

- 1953 – The Trials and Release of the P.O.Ws. Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Hastings 1987, p. 270: "169 of 850 Gloucesters mustered for rollcall with the brigade after the battle"

- Battle of the Imjin, Seoul: Office of the Defence Attaché, British Embassy, archived from the original on 26 February 2008, retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Hastings 1987, p. 269: '30 men died in captivity'

- Hastings 1987, p. 270 refers to several "campaign histories" when he puts the number at around 10,000 but underlines that the number of PVA casualties was "arbitrary" and based "upon the minimum that seemed credible"

- British Korean War Visit (outline of commemorations), Seoul: British embassy, 2008, archived from the original (MS Word) on 26 February 2008, retrieved 29 April 2008.

- War Department General Orders No. 3 (20 January 1954) Archived 18 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- Hastings 1987, p. xvii.

- "Colonel Peter Ormrod", The Times (obituary), London, 1 November 2007, retrieved 10 April 2008.

- General Orders, Department of the Army, 29 May 1952, archived from the original on 18 September 2006, retrieved 11 April 2008.

- The National Archives: American Presidential Citation, Catalogue reference: WO 32/14248 no.1B (8 May 1951). Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- Hendrik, The Belgian Forces in the Korean War (BUNC), At space, archived from the original on 30 March 2010, retrieved 22 August 2009.

- Hendrik, At space, archived from the original on 12 August 2013

Sources

- 3d Infantry Division (April 1951), "Section III, Narrative of Operations" (précis), American actions during the Battle of Imjin River (command report), The National Archives, Catalogue reference WO 308/47, retrieved 15 April 2008.

- Appleman, Roy (1990), Ridgway Duels for Korea, Military History Series, vol. 18, College Station, TX: Texas A and M University, ISBN 0-89096-432-7.

- Catchpole, Brian (2000), The Korean War, London: Constance & Roninson, ISBN 1-84119-413-1.

- Chae, Han Kook; Chung, Suk Kyun; Yang, Yong Cho (2001), Yang, Hee Wan; Lim, Won Hyok; Sims, Thomas Lee; Sims, Laura Marie; Kim, Chong Gu; Millett, Allan R (eds.), The Korean War, vol. II, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-7795-3.

- Chinese Military Science Academy (2000), 抗美援朝战争史 [History of War to Resist America and Aid Korea] (in Chinese), vol. II, Beijing: Chinese Military Science Academy Publishing House, ISBN 7-80137-390-1.

- Cunningham, Cyril (2000), No Mercy, No Leniency: Communist Mistreatment of British Prisoners of War in Korea, Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Leo Cooper, ISBN 0-85052-767-8.

- Farrar-Hockley, Anthony (1990), Official History: The British Part in the Korean War, vol. I. A distant obligation, London, ENG, UK: HMSO, ISBN 0-11-630953-9.

- ——— (1995), Official History: The British Part in the Korean War, vol. II. An honourable discharge, London, ENG, UK: HMSO, ISBN 0-11-630958-X.

- ——— (1996), "15. The Post War Army 1945–1963", in Chandler, David G; Beckett, IFW (eds.), The Oxford history of the British army, New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19280311-5.

- Fehrenbach, T. R. (2001), This kind of war: the classic Korean War history, Brassey's, ISBN 1-57488-334-8.

- Harding, E D (January 2011), The Imjin Roll (4th ed.), Rushden, Northamptonshire, England: Forces & Corporate Publishing, ISBN 9780952959762.

- Hastings, Max (November 1987), The Korean War (1st ed.), Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0-671-52823-2.

- Malkasian, Carter (2002), A History of Modern Wars of Attrition, Westport, CT: Praeger, ISBN 0-275-97379-4.

- Millett, Allan R (2010), The War for Korea, 1950–1951: They Came From the North, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 978-0-7006-1709-8.

- Mossman, Billy C (1990), Ebb and Flow: November 1950 – July 1951, United States Army in the Korean War, Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, ISBN 978-1-4102-2470-5, archived from the original on 29 January 2021, retrieved 14 June 2008

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Paik, Sun Yup (1992), From Pusan to Panmunjom, Riverside, NJ: Brassey, ISBN 0-02-881002-3

- Salmon, Andrew (2009), To the Last Round: The Epic British Stand on the Imjin River, London, UK: Aurum Press, ISBN 978-1-84513-408-2

- Salmon, Andrew (2010), To The Last Round: The Epic British Stand on the Imjin River, Korea 1951, Aurum, ISBN 978-1-84513-831-8

- Shrader, Charles R (1995), Communist Logistics in the Korean War, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-29509-3

- Stueck, William W (1995), The Korean War: An International History, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-03767-1

- Villahermosa, Gilberto N (2009), Honor and Fidelity: The 65th Infantry in Korea, 1950–1953, Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 9 November 2010

- Xu, Yan (徐焰) (1990), 第一次较量:抗美援朝战争的历史回顾与反思 [First Confrontation: Reviews and Reflections on the History of War to Resist America and Aid Korea] (in Chinese), Beijing: Chinese Radio and Television Publishing House, ISBN 7-5043-0542-1

- Zhang, Shu Guang (1995), Mao's Military Romanticism: China and the Korean War, 1950–1953, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0-7006-0723-4

Further reading

- American Presidential Citation, The National Archives, 8 May 1951, Catalogue reference WO 32/14248.

- Memorandum to the British Cabinet, The National Archives, 26 June 1950, Catalogue reference CAB 21/1985.

- "Citations for non-US recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross", Home of heroes, archived from the original on 18 September 2006.

- "Colonel Peter Ormrod—Tank commander who won the Military Cross for his bravery in the face of overwhelming Chinese odds in Korea", The Times (obituary), UK, 1 November 2007.

- Barclay, Cyril Nelson (1954), The First Commonwealth Division: The Story of British Commonwealth Land Forces in Korea, 1950–1953, Aldershot, UK: Gale & Polden.

- Cunningham-Boothe, Ashley; Farrar, Peter, eds. (1988), British Forces in the Korean War, London: The British Korean Veterans Association.

- Farrar-Hockley, Anthony (2007), The Edge of the Sword, London: Frederick Muller. 1955 edition was published by the Companion Book Club. OCLC 3192552

- Fehrenbach, TR (2001), This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History (50 ann ed.), US: Brassey's, ISBN 1-57488-334-8.

- Green, David (2003), Captured at the Imjin River: The Korean War Memoirs of a Gloster, Pen & Sword Books, ISBN 9781848846531, OCLC 751832966.

- Holles, Robert Owen (1972), Now Thrive The Armourers, White Lion. Resissued as Now Thrive the Armourers: A story of Action with the Gloucesters in Korea (November 1950-April 1951) by Bantam Books in 1989. ISBN 0553283219

- Kahn, Ely Jacques (1951), The Gloucesters: An Account of the Epic Stand of the Gloucestershire Regiment in Korea, London: Central Office of Information, OCLC 23865544.

- Large, Lofty (1999), Soldier Against the Odds: From Korean War to SAS, Mainstream, ISBN 978-1-84018-346-7.

- Rottman, Gordon (2002), Korean War Order of Battle. United States, United Nations and Communist Ground, Naval and Air Forces, 1950–1953, Praeger/Greenwood.

External links

- "The Imjin battle", The Korean War (documents, maps and images), UK: The National Archives.

- "The British involvement", The Korean War, The British Embassy, archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- The Battle of the Imjin River, The British Embassy, archived from the original on 26 February 2008, retrieved 3 November 2018, including a map showing the deployment of 29th Brigade's units.

- The Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum which holds the archives of the Gloucestershire Regiment including documents and artefacts related to the battle.

- "Korean War", Royal Engineers and the Cold War, Royal Engineers Museum, archived from the original on 28 February 2007.

- Royal Engineers Museum, archived from the original on 23 August 2007: Royal Engineer pictures of the Korean War.

- "Bernard Leroy Martin (one of three Bermudian Glosters at Imjin)", The Royal Gazette (obituary), 1 March 1997, archived from the original on 22 October 2009.

- "10th BATTALION COMBAT TEAM (MOTORIZED)", The Philippine contingent during the Korean War, Yahoo!, archived from the original on 22 October 2009, including their efforts to relieve the Gloucestershire Regiment.

- Hendrik, The story of the Belgian United Nations Command, At space, archived from the original on 12 August 2013 with reports of the battles they participated in, unit awards and personal decorations.