Battle of Kalijati

The Battle of Kalijati was a battle which occurred between 1 and 3 March 1942 during the Dutch East Indies campaign between invading Japanese forces and the Dutch colonial forces. It was fought over control of the Kalijati Airfield in Subang.

| Battle of Kalijati | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Battle of Java in the Dutch East Indies campaign | |||||||

KNIL vehicles destroyed during the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Initial: 530 Counterattack: 4,500 | 1,200 | ||||||

Location within Java | |||||||

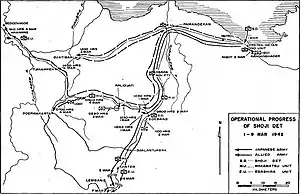

Following their unexpected landing, Japanese forces commanded by Toshinari Shōji moved rapidly and seized the airfield on the same day it landed before the Dutch command could deploy reinforcements. The following day, Dutch forces launched a counterattack in an attempt to retake the airfield, which nearly succeeded but eventually failed. The second, larger Dutch counterattack on 3 March was intercepted by Japanese air support which successfully prevented the majority of the Dutch units from launching the assault, forcing a Dutch retreat back to Bandung.

Prelude

During the Dutch East Indies campaign, following the Japanese capture of cities and islands outside Java (e.g. Tarakan, Balikpapan and Palembang), the Japanese command began preparations for the invasion of Java, which would involve the Sixteenth Army.[1] As part of the Japanese planning, a key objective was determined: the Kalijati Airfield close to Java's north coast, which was to be taken despite of risks involved.[2] Part of Java's invasion force (the 2nd Division and elements of the 38th Division) were assembled at Cam Ranh Bay to land in West Java, while the 48th Division was designated to land in East Java after moving through the Makassar Strait.[3]

On 27 February 1942, the Allies attempted to intercept the Japanese invasion fleet using the available naval assets in the region, but failed and suffered heavy losses.[4]

Forces and landings

Early on 1 March, at around 2 AM,[5] Japanese forces numbering around 23,500 in total began landing on multiple locations on Java, including one force assigned to Eretan Wetan (today in Indramayu Regency). The landing at Eretan Wetan, commanded by Colonel Toshinari Shōji, was directly targeted at Bandung, which housed the military and political headquarters of the Dutch and Allies in Java.[6] The Allied air force (mainly Royal Air Force warplanes) launched nighttime raids on the landing Japanese, but to little impact due to the poor weather conditions - Japanese Navy sources noted some injuries but commented that the attacks did not hinder the landings.[7] Later on, however, another air attack around daybreak caused around 100 casualties in the Shōji detachment.[8]

The Japanese had selected Eretan Wetan as a landing point as it was the landing point closest to roads, allowing a speedy deployment of motor vehicles for a fast assault on Kalijati.[9] Dutch command did not station any personnel near Eretan, however, as they did not expect a landing there due to personnel shortages and seasonal high tides in the area.[10] Coincidentally, the Shōji had not been equipped for combat during landing as they had also expected that their landings would be unopposed.[11]

Shōji's unit was based on a core of the 230th Regiment of the 38th Division, with supporting units numbering roughly 3,000 men in total.[12] The detachment was further subdivided into two "assault groups" and a covering group, with one of the assault groups (numbering around 1,200 men) under one Major Shichiro Wakamatsu being tasked with capturing the Kalijati Airfield.[5] The Kalijati airfield itself, 75 km (47 mi) distance from Eretan Wetan, was initially defended by a single KNIL company of 180 men under Lt. Col. J.J. Zomer, and was later replaced by 170 British personnel (including Army and RAF units) which arrived at night on 28 February as the KNIL soldiers instead took up defensive positions some distance away from the airfield itself, or held in reserve.[13] In total, including anti-air gunners already stationed at Kalidjati, there were 350 British troops there.[14] In the morning of 1 March, once the garrison was informed of the Japanese landings, the pilots of the RAF warplanes were ordered to move to Andir airfield in Bandung.[13]

Battle

By 6 AM, Wakamatsu's unit had departed the landing point and at 10:30 the forward units encountered KNIL units.[15] Japanese light tanks had by then come within firing range of the airfield and opened fire, and during the ensuing firefight planes took off just as the tanks entered the airfield. One plane was manned by just its pilot, who crept into his plane under Japanese fire.[16] On the other hand, Dutch forces stationed at Kalijati could not contact their commanders in Bandung regarding the impending Japanese attack until around 7 AM, as their communications were disrupted by heavy rainfall.[10] Shortly before the assault on Kalijati airfield, Japanese forces at their landing point fended off an attempted Dutch counterattack at Eretan Wetan, with Japanese reports estimating the number of counterattackers as between 400 and 500.[15]

Before long, the units guarding the airfield broke and escaped, and as the Japanese infantry arrived they took up positions, and stormed the last holdout positions whose personnel surrendered due to a lack of anti-tank armaments.[16] Around 80 of the surrendering British and Dutch troops were executed by the Japanese.[17]

Counterattacks

By early afternoon of 1 March, Dutch forces had hastily assembled a unit for a counterattack, including 24 light tanks, several armored vehicles, an infantry company, and three anti-tank guns. The unit left Bandung at 2 PM, but failed to reach their destination by nightfall and the attack had to be delayed to the following day.[18] Another larger unit (the "Teerink Group") of roughly 1,000 soldiers was also committed to recapturing the airfield, followed by KNIL's 2nd Infantry Regiment.[19] The first Japanese planes had arrived in Kalijati by around dusk on 1 March.[20]

2 March

At around 8:15 AM, the first group launched their attack on the Japanese troops around Subang. Despite initial success, in overrunning the first Japanese line of defence, the unit failed to dislodge the Japanese in the location of the town and after around two hours began to disengage, with combat ending by around noon. Dutch forces had lost at least 14 killed with a further 34 missing, with 13 of their tanks destroyed and 5 heavily damaged. The Japanese had suffered at least 20 killed.[21][22] Throughout the evening up until the following morning, the Allied air force launched reconnaissance and bombing missions to support the counterattack.[23]

Later Dutch assessment of the counterattack on 2 March noted that the Japanese had barely managed to hold against the assault.[21]

3 March

The primary Dutch unit for the counterattack was the reinforced KNIL's 2nd Infantry Regiment, which numbered around 3,500 in total, though most of their soldiers had no combat experience, save some attached units which fought in the Battle of Palembang. The unit was commanded by Major General Jacob Pesman.[24] The armored/motorized column heading from Bandung was however intercepted by Japanese aircraft, which managed to destroy over 150 vehicles and a significant amount of guns and ammunition, causing over 100 Dutch casualties.[25][26] By this time, several Japanese aerial units had redeployed to Kalijati.[26]

The air raids, while not causing too much casualties due to a lack of anti-personnel bombs on the Japanese side, significantly demoralized the KNIL soldiers and prevented their officers from regrouping their units after each air raid. Eventually, the soldiers, already exhausted from having been rapidly moved, broke and especially many of the non-European soldiers dispersed and fled. In total, some 300 men were recorded as dead, wounded or missing.[27] Just one element of the armored unit managed to reach the Japanese positions, and was driven off.[26] The Teerink Group was similarly demoralized by Japanese air raids and failed to launch a serious counterattack.[28] There was another assault by Dutch forces against Japanese landing positions at Eretan Wetan, but the attack was pinned down by Japanese artillery and was forced to withdraw, after losing some 30 men.[29] Most of the Japanese ground forces did not see much fighting against the Dutch counterattack.[30]

Aftermath

The KNIL's 2nd Infantry Regiment was effectively disabled following the intensive air raids, and could not participate in combat further. After securing the airfield, Shōji opted to immediately launch a direct assault against Bandung, leading to the Battle of Tjiater Pass.[31] Shōji's unit and its supporting air units later received citations of merit from Sixteenth Army Commander Hitoshi Imamura in the aftermath of the campaign for their actions at Kalijati (and later at Tjiater Pass).[32] Negotiations and the formal signing for the surrender of the Dutch East Indies later took place at the airfield.[33]

References

- OCMH 1958, pp. 1–3.

- Remmelink 2015, p. 38.

- Remmelink 2015, p. 37.

- Boer 2011, pp. 197–198.

- Boer 2011, p. 239.

- Boer 2011, p. 215.

- Boer 2011, p. 250.

- Remmelink 2015, p. 507.

- Remmelink 2015, p. 463.

- Boer 2011, p. 355.

- OCMH 1958, pp. 15–16.

- Boer 2011, p. 237.

- Boer 2011, pp. 261–265.

- Boer 2011, p. 273.

- Remmelink 2015, p. 508.

- Boer 2011, pp. 270–272.

- Borch, Frederic L. (2017). Military Trials of War Criminals in the Netherlands East Indies 1946-1949. Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-19-877716-8.

- Boer 2011, pp. 282–283.

- Boer 2011, p. 285.

- Boer 2011, p. 297.

- Boer 2011, pp. 302–303.

- Remmelink 2015, p. 509.

- Boer 2011, pp. 316–321.

- Boer 2011, pp. 334–335.

- Boer 2011, p. 339.

- Remmelink 2015, p. 513.

- Boer 2011, pp. 341–342.

- Boer 2011, pp. 343–346.

- Boer 2011, pp. 347–348.

- Boer 2011, p. 362.

- Boer 2011, pp. 366–367.

- Remmelink 2015, pp. 535–536.

- Remmelink 2015, pp. 529–534.

Bibliography

- Boer, P. C. (2011). The Loss of Java: The Final Battles for the Possession of Java Fought by Allied Air, Naval and Land Forces in the Period of 18 February - 7 March 1942. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-513-2.

- United States Army Forces in the Far East; Eighth U.S. Army (1958). The Invasion of the Netherlands East Indies (16th Army) (PDF). Office of the Chief of Military History. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- National Defense College of Japan (2015) [1967]. The invasion of the Dutch East Indies (PDF). Translated by William Remmelink. Leiden: Leiden University Press. ISBN 978-9087-28-237-0.