Battle of Kulikovo

The Battle of Kulikovo (Russian: Куликовская битва)[lower-alpha 1] was fought between the forces of Mamai and Russian forces led by Grand Prince Dmitry of Moscow.[8][9][10] The battle took place on 8 September 1380,[11] at Kulikovo Field near the Don River (now Tula Oblast, Russia) and was won by Dmitry,[12] who became known as Donskoy ("of the Don") after the battle.[12]

| Battle of Kulikovo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Troubles | |||||||

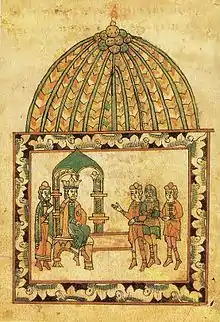

Dmitry Donskoy on the way to Kulikovo Field, miniature from the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Russian principalities:[2]

|

Mamai, controlling the western part of the Golden Horde

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Dmitry Ivanovich of Moscow Vladimir Andreyevich the Bold |

Muhammad Bolak | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30,000[4]–50,000/60,000[5] | 30,000[4]–100,000[6]/150,000[7] | ||||||

Although the victory did not end Mongol domination over Russia, it is traditionally regarded as the turning point at which Mongol influence began to wane and Moscow's power began to rise.[1][11] The battle would allow Moscow to strengthen its claims of ascendancy over the other Russian principalities,[13] in which it would ultimately become the center of a centralized Russian state.[14][15][16][17][18]

The victory at Kulikovo is commemorated in Russia as a Day of Military Honour.

Background

Following the Mongol invasion of Rus' in the 13th century, the numerous principalities became vassals of the Golden Horde.[19] During this period, the principality of Moscow was growing in power and was often challenging its neighbors over territory, including clashing with Ryazan. Thus, in 1300, Moscow seized the city of Kolomna from Ryazan, and the prince of Ryazan was killed after several years in captivity.[20]

After the killing of Khan Berdi Beg of the Golden Horde in 1359, a civil war had arisen there. Warlord (temnik) Mamai, who was son-in-law and beylerbey of Berdi Beg, soon took power in the western part of the Golden Horde. Mamai enthroned Abdullah Khan in 1361 and after his mysterious death in 1370, Muhammad Bolak was enthroned.[21] Mamai was not a Genghisid (descendant of Genghis Khan), and as such his grip on power was tenuous, as there were true Genghisids with claims to mastery. Therefore, he had to constantly fight for supreme power and at the same time struggle against separatism. While there was a civil war in the falling Golden Horde, the new political powers were appearing, such as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Grand Duchy of Moscow, and the Grand Duchy of Ryazan.

Meanwhile, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania continued its expansion. It competed with Moscow for supremacy over Tver and in 1368–1372 made three campaigns against Moscow. After the death of Algirdas in 1377, his eldest sons Andrei of Polotsk and Dmitri of Bryansk began to struggle with their step-brother Jogaila for their legitimate right to the throne and entered into an alliance with the Grand Prince of Moscow.[22]

Simultaneously with the beginning of the Great Troubles in the Horde in 1359, Prince of Moscow Ivan II died and the new Khan of the Horde by his jarliq (law pronouncement) transferred the throne of the Grand Duchy of Vladimir to the Prince of Nizhny Novgorod. But the Moscow elite (in 1359, new Prince Dmitry was only 9 years old) did not accept this. They used equally armed force and bribes to various Khans and as a result, in 1365, forced the princes of Nizhny Novgorod to finally give up claims to the Grand Duchy of Vladimir.[21] In 1368, the conflict between Moscow and Tver began. Prince of Tver Mikhail used the help of Lithuania, and in addition, in 1371 Mamai gave him a jarliq to the Grand Duchy of Vladimir. But the Moscow troops simply did not let the new "Grand Prince" enter to Vladimir, despite the presence of the Tatar ambassador. The campaigns of the Lithuanian army also ended in failure and so the jarliq returned to Dmitry. According to the results of the truce with Lithuania in 1372, the Grand Duchy of Vladimir was now recognized as the hereditary possession of the Moscow princes.[23] In 1375 the Prince of Tver once again received a jarliq for the Grand Duchy from Mamai. Then Dmitri with a strong army (larger than it was in the Kulikovo battle) quickly moved to Tver and forced it to capitulate. Mikhail recognized himself as the "little brother" of the prince of Moscow and ensure to participate in wars with the Tatars.[24]

The open conflict between Dmitry and Mamai began in 1374, the exact reasons are unknown. It is believed that the illegitimacy of the puppet khans of Mamai was by that time too obvious, and he demanded more and more money, as he lost the war for the throne of the Golden Horde.[25] In the following years the Tatars raided Dmitry's allies and the Moscow troops made campaign against Tatars over the Oka River in 1376 and seized the city Bolghar in 1377. In the same year "Mamai's tatars" defeated the army of Nizhny Novgorodl with an auxiliary detachment left by Dmitry at the Battle on Pyana River. The Tatars then began to raid Nizhniy Novgorod and Ryazan.[26]

Mamai continued attempts to re-affirm his control over the tributary lands of the Golden Horde. In 1378, he sent forces led by the warlord Murza Begich to ensure Prince Dmitri's obedience, but this army suffered crushing defeat at the Battle of the Vozha River. Meanwhile, another khan, Tokhtamysh, seized power in the eastern part of the Golden Horde. He enjoyed the support of Tamerlane and was ready to unite the entire Horde under his rule. In 1380, despite the threat from Tokhtamysh, Mamai chose to personally lead his army against the forces of Moscow. In preparation for the invasion, he entered into an alliance with Prince Jogaila of Lithuania. Ryazan Prince Oleg was defeated by Mamai in 1378 (and his capital was burnt), he had no strength to resist Mamai, and Ryazan's relationship with Moscow had long been hostile. Therefore, in the campaign of 1380 Oleg took the side of Mamai, although this fact is sometimes challenged. Mamai camped his army on the bank of the Don River, waiting for the arrival of his allies.[27][28]

Prelude

Campaign

In August 1380 Prince Dmitri learned of the approaching army of Mamai. It is alleged that Oleg Ryazansky sent a message to him. The interpretations of such an act are different. Some believe that he did this because in fact he was not a supporter of Mamai, while others believe that he expected to intimidate Dmitry - in the past, none of the Russian princes dared to meet in battle with the Khan himself. Nevertheless, Dmitry quickly assembled an army in Kolomna. There he was visited by the ambassadors of Mamai. They demanded an increased tribute, "as under the Khan Jani Beg". Dmitry agreed to pay tribute, but only in the amount provided for by his previous contract with Mamai.[29] In Kolomna, Dmitry received updated information about the Mamai itinerary and about approaching forces of Jogaila. So, after reviewing the army, on August 20 he moved west along the Oka River, crossed it at the town Lopasnya on August 24–25 and moved south towards Mamai. On September 6, the Russian army reached the Don River, where it was reorganized, taking into account the units that joined during the movement from Kolomna. At the council it was decided to cross the Don before the enemies could combine their forces, although this step cut off the path to retreat in case of defeat.[30]

Forces

The earliest chronicle tales do not provide details on the composition of the Russian army. Among the dead in the battle there are named only Princes of Beloozero (which by that time were in strong submission to Moscow), noble Moscow boyars, and Alexander Peresvet.[31] The latter, according to some sources, was from Lithuania (rather from Bryansk). The poetic story "Zadonshchina", along with a figure of 253,000 fallen in the battle, gives dozens of dead princes, boyars, "Lithuanian pans" and "Novgorod posadniks" from all over North-Eastern Rus', but all this data is doubtful. There are mentioned even 70 fallen Ryazan boyars, although according to all other sources the Duchy of Ryazan was the forced ally of Tatars. According to the Russian historian Gorskii, the list of princes and commanders (according to which one can estimate the composition of the army), cited in "The Tale of the Rout of Mamai" and the sources derived from it, is completely untrustworthy. However, he identified two chronicles with a sufficiently high level of reliability. According to his reconstruction, detachments from most of North-Eastern Russia, part of the Princes of the Smolensk Land and part of the Upper Oka Principalities were represented in the army of Dmitry, but there were no troops from Nizhny Novgorod and from the Principality of Tver (except for Kashin, who became independent under the treaty of 1375). The probability of the presence of a detachment from Veliky Novgorod is quite high (although in the early Novgorod chronicles such information is not available). Grand Duchy of Ryazan could be represented by the troops of the appanage Principality of Pronsk, whose rulers have long rivaled their Grand Princes. Also, the presence of small detachments from the border lands of Murom, Yelets and Meshchera is "not excluded". Probably, the army of Dmitri was enforced by Jogaila's rebellious brothers Andrei of Polotsk and Dmitri of Bryansk.[2]

The first data on the total number of troops collected by Dmitry appeared in the Expanded Chronicle Tale, which estimates them in 150–200,000. This number is completely unreliable, as such masses of people simply could not physically fit on the field; even the number of 100,000 seems overestimated. Late literature sources determine the number of Russian troops at 300,000 or even 400,000 armored soldiers only. Thus, there is no exact data on the number of the army of Dmitry. It can only be said that by the standards of that time it was a very large army, and even in the 15th century the Moscow princes could not assemble an equally powerful force, which led to fantastic stories about hundreds of thousands of warriors.[32] The definition of the real size of the medieval armies on the basis of chronicles is a difficult task.[33]

Estimates of the number of the Russian army by historians gradually departed from the hundreds of thousands of soldiers described in the chronicles and medieval literature. Military historian General Maslovsky in the work of 1881 estimated it to be 100,000–150,000. The historian of military art Razin in the book of 1957 estimated it to be 50,000–60,000. The historian and archaeologist, medieval warfare expert Kirpchinikov, in the book of 1966 argues that the maximum strength of the army of six regiments on Kulikovo Field could not exceed 36,000. Archaeologist Dvurechensky, an employee of the "Kulikovo field" museum, in his report of 2014 determined the number of the Russian army in 6,000–7,000 warriors. Close assessments are given by modern Russian historians Penskoy and Bulychev. The main impetus for reducing the estimates of the strength of the army was the analysis of demography and mobilization potential. It was noted that even a much larger and densely populated Russia of the 16th century rarely could expose 30,000–40,000 soldiers at a time. It was also noted that the timeframe for mobilization (about two weeks) was too small to mobilize a huge army of unskilled militiamen (even apart from the fact that this approach was completely contrary to all the military traditions of that time).[34][35][36][37][38] Attempts to reduce the size of the army are criticized by some authors.[39]

Estimates of the forces of the Tatars in Russian sources are equally unreliable, they only show an overwhelming numerical superiority. So, in one variant of "The Tale" the number of Russians troops was boldly given at 1,320,000 but the Tatar army was named "innumerable".[40] There were no medieval sources from the Tatar side.[41] Mamai's allies, Grand Prince Oleg II of Ryazan and Grand Prince Jogaila of Lithuania, were late to the battle and the number of their troops can be ignored.

Battle

Intro

The early sources contain few details about the course of the battle. "The Tale of the Rout of Mamai", which dates back to the 16th century, gives a complete picture detailing the alignment of forces and the events on the field, and adds many colorful details. It is unknown whether "The Tale" is based on an unknown earlier source, or whether it reflects a retrospective attempt to describe the battle based on tactics and practices of the 16th century. Due to the absence of other sources, the course of the battle according to "The Tale" was adopted as a basis for subsequent reconstructions of the battle.[43]

On 7 September, Prince Dmitri was told that Mamai's army was approaching. On the morning of 8 September, in a thick fog, the army crossed the Don River. According to the Nikon Chronicle, after that the bridges were destroyed. The day of 8 September was very special, as it was the feast of the Nativity of the Theotokos, who was considered a patron Saint of Russia. According to chronology adopted in Russia it was the year 6888 Anno Mundi, which also had a numerological value.[44] The army came to the "clean field" near Nepryadva mouth and assumed a battle formation. After some time, Tatars appeared and began to form their order of battle against the "Christians".[45]

Beginning

The Russian army was organized into six "regiments" - a Patrol, a Forward, two regiments of "Right" and "Left Hand," a Large regiment and an Ambush regiment. In turn, each of the regiments was divided into smaller tactical units – "banners" (a total of about 23).[46] On the field the army was arranged in multiple lines, and probably, the location of the regiments did not match their names (there is no evidence that the regiments of the Left and Right Hand disposed in line with the Large Regiment). The terrain did not allow for a broad front; probably, the units entered into battle gradually. The army's flanks were protected by ravines with dense thickets which excluded any chance for a surprise flank attack of a Horde. The Ambush regiment under the command of Vladimir the Bold and Dmitry Bobrok (brother-in-law of the Grand Prince) was hidden behind the line of Russian troops in an oak grove.[lower-alpha 2] The Grand Prince himself went to the front lines, leaving his trusted boyar Mikhail Brenok as the head of the Large Regiment under the great banner. He also exchanged with the boyar horses and gave him a coat and a helmet, so the Grand Prince could fight like an ordinary boyar, remaining unrecognized.[lower-alpha 3] The battle opened with a single combat between two champions.[lower-alpha 4] The Russian champion was Alexander Peresvet and the Horde's champion was Temir-Murza (also Chelubey or Cheli-bey, also Tovrul or Chrysotovrul). During the first pass of the contest each champion killed the other with his spear and both fell to the ground. Thus, it remained unclear whose victory was predicted by the outcome of the duel.[47]

Main clash

After the fights of the advanced detachments, the main forces of both armies clashed. According to the "Expanded Chronicle Tale" it happened "at the sixth hour of the day" (the daylight was divided into twelve hours, the duration of which changed throughout the year).[lower-alpha 5] "The sixth hour of the day" approximately corresponds to 10.35 am. According to one of the later sources, the Tatars met the first blow of the Russian cavalry on foot, exposing the spears in two rows, which gave rise to stories about the "hired Genovese infantry." Russian sources, even the earliest ones, unanimously tell us that after the clash of the main forces, a cruel melee began, which lasted a long time and in which the "innumerable multitude of people" perished on both sides.[48] The medieval German historian Albert Krantz describe this battle in his book Vandalia: "both of these people do not fight standing in large detachments, but in their usual way they rush to throw missiles, strike and then retreat backwards". An expert on the medieval warfare, Kirpichnikov assumed that the armies on the Kulikovo field fought by a number of separate consolidated units, that tried to keep the battle order. As soon as this order was disrupted, the survivors from the unit fled and a new detachment was put in their place. Gradually, more and more units were drawn into the battle. As described in the "Expanded Chronicle Tale": "And a corpse fell on a corpse, a Tatar body fell on a Christian body; then here, it was possible to see how a Rusyn pursued a Tatar, and a Tatar pursued a Rusyn." The tightness of the field did not allow the Tatars to realize their mobility and use their tactics of flanking. Nevertheless, in a fierce battle the Tatars began to gradually overcome. They broke through to the banner of the Large Regiment, threw it down and killed boyar Brenok. The regiment of the "Left Hand" was also overturned and some "Moscow recruits" fell into a panic.[lower-alpha 6] It seemed that the rout of the Russian army was close and the Tatars put all their forces into action.[49]

At that time, the cavalry of the ambush regiment launched a surprise counterstrike on the Horde's flank, which led to the collapse of the Horde's line. People and horses, tired from a long battle, could not resist the blow of fresh forces. After the Horde was routed, the Russians chased the Tatars for over 50 kilometres (31 mi), until they reached Krasivaya Mecha River.[50]

End

The losses in the battle were great. A third of the commanders of 23 "banners" were killed in action. Grand Prince Dmitry himself survived, although wounded and fainted from exhaustion. His entire escort died or scattered and he was hardly found among the corpses. For six days the victorious army stood "on the bones".[51]

Aftermath

Upon learning of Mamai's defeat, Prince Jogaila turned his army back to Lithuania. People of the Ryazan Land attacked separate detachments coming from the battlefield, plundered them and taken prisoners (the question of the return of prisoners remained actual for twenty years, it was mentioned in the Moscow–Ryazan Treaties of 1381 and 1402). Prince Dmitry of Moscow began to prepare for reprisal, but Prince Oleg of Ryazan fled (according to the Nikon Chronicle, "to Lithuania") and the Ryazan boyars received Moscow governors. Soon Prince Oleg returned to power, but he was forced to accept Prince Dmitry as his sovereign ("older brother") and to sign a treaty of peace.[52]

Mukhammad-Bulek, Mamai's figurehead Khan, was killed in battle. Mamai escaped to the Genoese stronghold Caffa in Crimea. He assembled a new army, but now he did not have a "legitimate khan" and his nobles defected to his rival Tokhtamysh khan. Mamai again fled to Caffa and was killed there.[53] The war with Moscow had led Mamai's Horde to a complete crash. With one stroke Tokhtamysh received full power, thus eliminating the 20-year split of the Golden Horde. According to historian Gorsky, it was Tokhtamysh who received the most concrete political benefit from the defeat of Mamai.[54]

Prince Dmitri, who became known as Donskoy (of the Don) after the battle, did not manage to become fully independent from the Golden Horde, however. In 1382, Khan Tokhtamysh launched another campaign against the Grand Duchy of Moscow. He captured and burned down Moscow, forcing Dmitri to accept him as sovereign. However, the victory at Kulikovo was an early sign of the decline of Mongol power. In the century that followed, Moscow's power rose, solidifying control over the other Russian principalities. Russian vassalage to the Golden Horde officially ended in 1480, a century after the battle, following the defeat of the Horde's invasion at the great stand on the Ugra River.

Legacy

Primary sources about the battle

Only five primary sources about the battle have survived into modern times: one in Church Slavonic, two in Middle High German, and two Bolgar sources.[55] No sources from the Tatar side are available; if they had been written, they were probably destroyed a few years later when Timur burnt down the archives of the Golden Horde in Sarai.[55]

- A common Slavonic source for the earliest three "literary works of the Kulikovo cycle", the oldest of which were probably the "Chronicle Tale" and the Zadonshchina, while the Skazanie o Mamaevom poboishche ("Narration of the Battle with Mamai") was largely derived from the Zadonshchina (see below).[56] Some Turkic words, phrases and steppe terminology are found in this source, which has led some scholars to propose the original text was written in Old Tatar or Bolgar, but these could be loanwords and other borrowings, and do not rule out that the source was originally written in Slavonic.[57]

- The chronicle of Johann von Posilge, Chronik des Landes Preussen[3] (originally in Latin, translated to German)

- The chronicle of Detmar of Lübeck,[3] preserved as the Ratshandschrift

- Two Bolgar manuscripts from the end of the 17th or 18th century[58]

Each of the literary works of the Kulikovo cycle contains at least some historical errors or fictions.[59] The earliest three works ("Chronicle Tale", Zadonshchina and "Narration") probably derived from a common source.[59] Scholars usually consider the "Narration" to be the youngest version of this Slavonic primary source, and the least reliable, but even scholars who claim it has some historical elements have openly admitted that it has its flaws.[59] For example, the "Narration" mistakenly claimed that Cyprian, Metropolitan of Kiev in 1380 resided in Moscow rather than Kyiv,[59] that Algirdas (died 1377) was still grand duke of Lithuania in 1380,[59] and that Dmitry Donskoy had a meeting with Sergius of Radonezh, which almost certainly did not happen.[59] They also contradict each other on some fundamentals such as Donskoy's role during the battle.[58] According to the "Narration", Donskoy fought on horseback with his own clothes, was wounded and left the field of battle, and was found unconscious under a tree after the battle; according to the "Chronicle Tale", Donskoy switched clothes with a boyar, fought in the frontline until the end of combat, and did not sustain even a scratch.[58] The style of the Slavonic sources also differs significantly: the Zadonshchina is a rather chivalric and militaristic story with only superficial religious elements, while the "Narration" is a very Christian religious retelling of the events narrated in the Zadonshchina.[60]

The two German chroniclers were not eyewitnesses, but in all likelihood received their information from Lithuanian informants, who had their own biases.[3] According to Ostrowski (1998, 2000), the German chronicles were generally earlier and more accurate than the Kulikovo cycle sources, and showed that the battle did take place on the Don river, but was not as significant as claimed.[3]

Literary works of the Kulikovo cycle

The Battle of Kulikovo gave rise to an unprecedentedly large stratum of medieval Rus' literature; no other historical event has received such wide coverage. Russian historians singled out a body of "literary works of the Kulikovo cycle",[61][62] or "Kulikovo cycle" for short.[62] The most important works are:[63]

- Letopisnaia povest’, or "Chronicle Tale", passed down in two redactions:[56]

- Kratkaia letopisnaia povest’, or "Short Chronicle Tale",[56] preserved in the Rogozh Chronicle (c. 1450[64]) and Simeon Chronicle[65] (c. 1490s[64])

- Prostrannaia letopisnaia povest’, or "Expanded Chronicle Tale",[56] preserved in the Novgorod Fourth Chronicle[64] (c. 1480s[64]) and Sofia First Chronicle[64] (c. 1480s[64])

- Zadonshchina, or "The Battle beyond the Don", a famous epic based on or influenced by The Tale of Igor's Campaign.[62] The earliest manuscript dates to the 1470s.[59]

- Skazanie o Mamaevom poboishche, or "The Tale of the Battle with Mamai",[62] also known as "Narration of the Battle with Mamai".[66]

- Slovo o zhitii i prestavlenii velikogo kniazia Dmitriia Ivanovicha, or "Oration Concerning the Life and Passing of Grand Prince Dmitrii Ivanovich",[62] or Encomium to Dmitrii Ivanovich[67] ("Expanded Redaction" c. 1449–1470s[67])

- Life of St. Sergii of Radonezh (c. 1418)[68]

While the Zadonshchina is clearly based on the literary model of The Tale of Igor's Campaign (also known as Lay of the Host of Igor’),[62][69] the latter had elements of Slavic paganism, which in the Zadonshchina narrative were replaced by the idea that the Rus' soldiers fought "for the Rus’ Land and the Christian faith";[69] yet the Christian elements in it pale in comparison to its military and chivalric ethos.[60] On the other hand, the "Narration of the Battle with Mamai", which has been largely derived from the Zadonshchina, is "a highly religious depiction of the battle, replete with constant prayers, miracles, and religious symbolism".[60] As of 2022, there were 6 known manuscripts of the Zadonshchina, while over a hundred copies of the "Narration" have survived, indicating the greater popularity of these later versions, which systemically rewrote various episodes from the Zadonshchina to make them more religious.[60] For example, the "Narration" adds an invocation of Volodimer I of Kiev baptising the Rus' Land, Alexander Peresvet pronouncing a prayer before going into battle, and unlike in the Zadonshchina, nobody is said to be fighting "for the Rus' Land", but only "for the Christian faith and Grand Prince Dmitrii Ivanovich".[60]

Art

The paintings on the theme of the battle were created by many Russian and Soviet artists such as Orest Kiprensky, Vasily Sazonov, Mikhail Nesterov, Alexander Bubnov, Mikhail Avilov. The French painter Adolphe Yvon, later known for his works on the Napoleonic Wars, in 1850 wrote the monumental painting "The Battle of the Kulikovo Field" by order of Nicholas I.[70]

Dedications

The site of the battle is commemorated by a memorial church, built from a design by Aleksey Shchusev.

A minor planet, 2869 Nepryadva, discovered in 1980 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh, was named in honor of the Russian victory over the Tataro-Mongols.[71]

Archaeological searches

Location

Medieval sources do not give a precise description of the site of the battle, but they mention a large clear field beyond the Don River and near the mouth of the Nepryadva River. In the 19th century, Stepan Nechaev came up with what he believed was the exact location of the battle and his hypothesis was accepted. Studies of old soils in the 20th century showed that the left bank of Nepryadva near its influx in the Don was covered with dense forests, while on the right there was a wooded steppe with vast openings. On one of them, between the rivers Nepryadva and Smolka, the place of the battle was finally localized by a team of archeologists led by Dvurechensky in 2005.[72]

The historian Azbelev (2016) subjected this localization to sharp criticism. Trying to prove that 400,000 people were involved in the battle on both sides, he assumed that the real battlefield was not at the mouth, but at the source of Nepryadva, since the Old Russian word ust'e had also designated the place where the river flows from the lake.[73] As early as the beginning of the 20th century, it was believed that Nepryadva derived from Lake Volovo (Volosovo).[74]

Searches for traces

The first searches for traces of the battle were done by amateurs in the 18th and 19th centuries by asking for items from peasants who plowed the land, and frequently reported having discovered fragments of "weapons, baptismal crosses, icons, medallions and other items" that were allegedly related to Kulikovo.[75] It is known that at the time some of the finds were collected by economist Vasily Lyovshin, who had a personal interest in the history of the battle. A large number of antiquities were discovered in the 19th century and their relatively large number led to the publication of the first catalogue of Kulikovo artifacts by Ivan Sakharov, Secretary of the Department of Russian and Slavic Archaeology of the Imperial Russian Archaeological Society. Historian Stepan Nechayev noted in his writings that during their agricultural operations local peasants discovered old weapons, crosses, chainmails, and used to find human bones before; some of those finds were purchased by him, and their description appeared on the pages of Vestnik Evropy.

In 1825, it was reported by a famous Russian adventurer that the "precious things" from the field, once numerous, were "scattered across Russia" and formed private collections, such as those of Nechayev, Countess Bobrinskaya and other noble persons. The fate of these collections is not always clear and not all of them have been preserved to this day; General Governor Alexander Balashov and educator Dmitri Tikhomirov pointed to the fact that in their time iron objects were often collected, melted down by peasants and used for their purposes. One of such cases occurred recently, in 2009, when a Persian blade dug out from the field was discovered in the house of a local family and transferred to the Kulikovo field museum. After visiting the field and the village of Monastyrschina, Tikhomirov noted that "swords, axes, arrows, spears, crosses, coins and other similar things" that were of value were frequently found there and owned by private persons. Numerous fragments of weapons, crosses and armour were also noted by the famous 19th-century Tula historian Ivan Afremov, who suggested building a museum for these artifacts. Some of the finds are known to have been sent as gifts to government officials and members of the Imperial family; in 1839 and 1843, the head of a mace and the blade of a sword were gifted to Emperor Nicholas I by a Kulikovo nobleman.

While preparing his work "Parishes and Churches of the Tula Diocese" (1895), editor Pavel Malitsky received reports from inhabitants of the Tula Oblast, who had found spearheads, poleaxes and crosses on the field. Spears and arrows dug out by the locals are also mentioned in the worksheets of the Tula provincial academic archival commission. Many artifacts were collected by noble families that owned Kulikovo, such the Oltufyevs, the Safonovs, the Nechayevs and the Chebyshevs, whose rich collections were still remembered by local citizens in the 1920–1930s. Their estates were situated around the village of Monastyrschina, close to the site of the battle, but during the Civil War most of their collections were lost and only a significant part of the Nechayevs’ collection survived the revolutionary period, whereas the extensive use of agricultural machinery in the field contributed to a loss of remaining artifacts. A number of antiquities, however, were found and transferred to museums in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[76]

Works on relics from Kulikovo were published in the 1920s and 1930s by local lore specialists Vladimir Narcissov and Vadim Ashurkov. Most recent descriptions of Kulikovo weaponry and other artifacts have been presented in publications by Vasily Putsko, Oleg Dvurechensky and other historians.[77][78][76]

The 2008 book by Dvurechensky et al. presents a catalog of findings at the Kulikovo field. According to the compilers, the following items of weapons belong to the time of the battle: four spearheads (and two fragments), a tip of a javelin, two fragments of ax blades, a fragment of an armor plate, a fragment of chain mail, and several arrowheads. Many weapons found in the vicinity of the Kulikovo field (such as bardiches, firearms), date back to the 16th–18th centuries and cannot in any way relate to the Kulikovo battle of 1380.[77]

Perspectives

The historical evaluation of the battle has many theories as to its significance in the course of history:

- The traditional slavophile Russian point of view sees the battle as the first step in the liberation of the Russian lands from the Golden Horde dependency. However, approximately a half of the old Kievan Rus' at this time were controlled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

- Some historians within the Eastern Orthodox tradition view the battle as a stand-off between the Christian Rus and non-Christians of the steppe.

- Russian historian Sergey Solovyov saw the battle as critical for the history of Eastern Europe in stopping another invasion from Asia, similar to the Battle of Châlons in the 5th century and the Battle of Tours in the 8th century in Western Europe.

- Other historians believe that the meaning of the battle is overstated, viewing it as nothing more than a simple regional conflict within the Golden Horde.

- Another Russian historian, Lev Gumilev, sees in Mamai a representative of economic and political interests from outside, particularly Western Europe, which in the battle were represented by numerous Genoese mercenaries, while the Moscow army stood in support of the rightful ruler of the Golden Horde Tuqtamış xan. According to the Russian historian Lev Gumilev, "Russians went to the Kulikovo field as citizens of various principalities and returned as a united Russian nation".[79]

- The battle is perhaps the earliest example of the Russian tactic of deception, or maskirovka, and it is taught as such at Russian military schools.

See also

- Oslyabya, Russian monk

- Russo-Kazan Wars

Notes

- Also known in Russian as Мамаево побоище or Донское побоище

- A detailed account of the location and actions of the Ambush Regiment is contained only in "The Tale of the Rout of Mamai", but with an important note that it was written by the words of a spectator and participant. In addition, the formation and command structure of this regiment is described in credible chronicles (Amel'kin & Seleznev 2011, p. 235)

- The episode with disguise appears only in "The Tale of the Rout of Mamai", but already in the "Expanded Tale" it is said about how Dmitry drove off to the Patrol Regiment and took part in the attack in the first line. Then he returned to his place in the Large Regiment and his retinue tried to dissuade him from such reckless behavior. But he refused and again fought in the front ranks and his armor was damaged in many places. This behavior was not something exceptional for the rulers of that time. Dmitry Donskoy's grandson Vasily II in one of the battles with the Tatars was surrounded and taken prisoner after a brutal melee, although armor saved his life, like his grandfather.

- This episode appears only in "The Tale of the Rout of Mamai" and there are serious suspicions that this is the product of literary fiction. The book of Amel'kin & Seleznev 2011, p. 238 lists 6 arguments in favor of this. In "Zadonschina" Peresvet does not fight in a duel, but in the thick of the battle, and not as a monk, but as a noble boyar in a gold-plated armor.

- According to "The Tale of the Rout of Mamai" it happened "at the third hour", but this information is doubtful. Chronicle data are more reliable, and, in addition, "The Tale" mentions earlier that the formation of regiments continued until "the sixth hour of the day" (Rybakov 1998, pp. 215–216, 218).

- Reconstructions of the battle traditionally draw a breakthrough of the Tatars on the left flank of the Russian troops, but there is no direct indication of such a course of events in the medieval sources. The description that the battle line of the Russian army was broken and the regiment of the Left Hand was cut off appears only in the work of the historian of the 18th century Tatischev.

References

- Borrero 2009, p. 208.

- Gorskii, Anton (2001). "К вопросу о составе русского войска на Куликовом поле" (PDF). Древняя Русь. Вопросы медиевистики. 6: 1–9.

- Halperin 2016, p. 10.

- L. Podhorodecki, Kulikowe Pole 1380, Warszawa 2008, s. 106

- Разин Е. А. История военного искусства VI–XVI вв. С.-Пб.: ООО «Издательство Полигон», 1999. 656 с. Тираж 7000 экз. ISBN 5-89173-040-5 (VI–XVI вв.). ISBN 5-89173-038-3. (Военно-историческая библиотека)

- Карнацевич В. Л. 100 знаменитых сражений. Харьков., 2004. стр. 139

- Мерников А. Г., Спектор А. А. Всемирная история войн. Минск., 2005.

- Moss 2003, p. 82.

- Galeotti 2019, p. 6, Russians, with Grand Prince Dmitry at the centre.

- Borrero 2009, p. 208, The Russian armies, led by Grand Prince Dmitrii of Moscow, son of Ivan II.

- Kort 2008, p. 21.

- Bushkovitch 2011, p. 23.

- Crummey 2014, p. 53, Certainly Kulikovo did not free the Russian principalities... The victory at Kulikovo, however, greatly increased the prestige of the ruler of Moscow.

- Timofeychev, A. (2017-07-19). "The Battle of Kulikovo: When the Russian Nation Was Born". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- Borrero 2009, p. 208, It strengthened the claims of the rulers of Moscow to an ascendancy over the other Russian principalities. But it marked only the beginning of the end of Mongol rule over Russia.

- Meyendorff, John (24 June 2010). Byzantium and the Rise of Russia: A Study of Byzantino-Russian Relations in the Fourteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-521-13533-7.

- Kort 2008, p. 21, Moscow's strength, especially relative to other Russian principalities, continued to grow.

- Keller 2020, p. 25, Two years later... the Russians were actually under harsher Mongol control... Despite this, Dmitri had laid important groundwork for Moscow's future dominance.

- Benz, Ernst (31 July 2008). The Eastern Orthodox Church: Its Thought and Life. Transaction Publishers. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-202-36575-6.

- Gorskii 2000, pp. 28–29, 44.

- Gorskii 2000, pp. 80–82.

- Auty, Robert; Obolensky, Dimitri (1981). A Companion to Russian Studies: An Introduction to Russian History. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 0-521-28038-9.

- Gorskii 2000, pp. 83–85.

- Gorskii 2000, pp. 90–92.

- Gorskii 2000, pp. 86–89.

- Gorskii 2000, pp. 90, 92–93.

- Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts On File. p. 543. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3.

- Robert O. Crummey (2014). The Formation of Muscovy 1300–1613. Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-317-87200-9.

- Gorskii 2000, p. 97.

- Kirpichnikov 1980, pp. 37–43.

- Rybakov 1998, p. 18.

- Rybakov 1998, pp. 51–52.

- Christian Raffensperger (2018). Conflict, Bargaining, and Kinship Networks in Medieval Eastern Europe. Lexington Books. pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-1-4985-6853-1.

- Масловский Д.М. Из истории военного искусства России: Опыт критического разбора похода Дмитрия Донского 1380 г. до Куликовской битвы включительно // Военный сборник. СПб., 1881. № 8. Отд. 1.

- Разин, Е. А. История военного искусства в 3 т. Т. 2 : История военного искусства VI–XVI вв. – СПб. : Полигон, 1999. – 656 с. – ISBN 5-89173-040-5

- Кирпичников А.Н. Военное дело на Руси в XIII–XV вв. - Л.: Наука, 1966, с. 16

- Двуреченский О.В. Масштабы Донского побоища по данным палеографии и военной археологии Archived 2022-10-10 at the Wayback Machine // Воинские традиции в археологическом контексте. От позднего латена до позднего средневековья. – Тула: Куликово поле, 2014. c. 124–129

- Пенской В.В. О численности войска Дмитрия Ивановича на Куликовом поле // Военное дело Золотой Орды: проблемы и перспективы изучения. Казань, 2011, стр. 157–161

- Азбелев С.Н. Куликовская битва по летописным данным //Исторический формат, 2016

- Rybakov 1998, pp. 277, 308.

- Amel'kin & Seleznev 2011, p. 60.

- Parppei 2017, p. 205.

- Parppei 2017, pp. 57, 80–83, 231.

- Рудаков, Владимир (1998). "Духъ южны" и "осьмый час" в "Сказании о Мамаевом побоище" (К вопросу о восприятии победы над "погаными" в памятниках "куликовского цикла"). Герменевтика древнерусской литературы (in Russian). 9: 135–157.

- Kirpichnikov 1980, p. 88.

- Kirpichnikov 1980, p. 51.

- Kirpichnikov 1980, pp. 89–92.

- Rybakov 1998, p. 9.

- Kirpichnikov 1980, pp. 94–99.

- Kirpichnikov 1980, pp. 99–100.

- Kirpichnikov 1980, pp. 100–104.

- Amel'kin & Seleznev 2011, pp. 248–249.

- Amel'kin & Seleznev 2011, p. 246.

- Gorskii 2000, p. 100.

- Halperin 2016, p. 4.

- Halperin 2016, p. 6–8.

- Halperin 2016, p. 7–8.

- Halperin 2016, p. 8.

- Halperin 2016, p. 7.

- Halperin 2022, p. 14.

- Rybakov 1998, p. 5.

- Plokhy 2006, p. 70.

- Parppei 2017, pp. ix, 20.

- Halperin 2001, p. 256.

- Halperin 2001, p. 254.

- Halperin 2016, p. 6.

- Halperin 2001, p. 255.

- Plokhy 2006, p. 71.

- Halperin 2022, p. 13.

- "Куликово поле: 12 картин".

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 236. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- Где была Куликовская битва. В поисках Куликова поля – интервью с руководителем отряда Верхне-Донской археологической экспедиции Государственный исторический музей Олегом Двуреченским. Журнал «Нескучный Сад» № 4 (15) 15.08.05

- Azbelev, Sergey (2016). "Место сражения на Куликовом поле по летописным данным" (PDF). Древняя Русь. Вопросы медиевистики. 3 (65): 17–29.

- "ЭСБЕ/Непрядва" [ESBE/Nepryadva]. ru.wikisource.org (in Russian). Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- "Searches and discoveries". en.kulpole.ru. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- "История изучения реликвий Куликовской битвы" [History of the study of relics of the Battle of Kulikovo]. kulpole.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 4 January 2019.

- Двуреченский О. В., Егоров В. Л., Наумов А. Н. Реликвии Донского побоища. Находки на Куликовом поле / авт.-сост. О. В. Двуреченский. М.: Квадрига, 2008. 88 с. (Реликвии ратных полей / Гос. ист. музей, Военно-ист. и природный музей-заповедник "Куликово поле"). ISBN 978-5-904162-01-6

- М. В. Фехнер Находки на Куликовом поле // Куликово поле: Материалы и исследования. Труды ГИМ. М., 1990. Вып. 73

- Lev Gumilev. From Rus to Russia

Bibliography

- Amel'kin, Andrei; Seleznev, Yuri (2011). Куликовская битва в свидетельствах современников и памяти потомков [The Battle of Kulikovo in the Testimonies of Contemporaries and Memory of Posterity)] (in Russian). Moscow: Квадрига. pp. 384, illus. ISBN 978-5-91791-074-1.

- Borrero, Mauricio (2009). Russia: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-7475-4.

- Bushkovitch, Paul (5 December 2011). A Concise History of Russia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-50444-7.

- Crummey, Robert O. (6 June 2014). The Formation of Muscovy 1300 - 1613. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87200-9.

- Galeotti, Mark (19 February 2019). Kulikovo 1380: The Battle that Made Russia. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1-4728-3121-7.

- Gorskii, Anton (2000). Москва и Орда [Moscow and the Horde] (in Russian). Moscow: Наука. p. 214. ISBN 5-02-010202-4.

- Halperin, Charles J. (2001). "Text and Textology: Salmina's Dating of the Chronicle Tales about Dmitrii Donskoi". Slavonic and East European Review. 79 (2): 248–263. doi:10.1353/see.2001.0046. S2CID 247621602. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- Halperin, Charles J. (17 February 2016). "A Tatar interpretation of the battle of Kulikovo Field, 1380: Rustam Nabiev". Nationalities Papers. 44 (1): 4–19. doi:10.1080/00905992.2015.1063594. ISSN 0090-5992. S2CID 129150302.

- Halperin, Charles J. (2022). The Rise and Demise of the Myth of the Rus' Land (PDF). Leeds: Arc Humanities Press. p. 116. ISBN 9781802700565.

- Keller, Shoshana (2020). Russia and Central Asia: Coexistence, Conquest, Convergence. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-9434-3.

- Kirpichnikov, Anatoly (1980). Куликовская битва [Battle of Kulikovo (in Russian)] (in Russian). Leningrad: Наука.

- Kort, Michael (2008). A Brief History of Russia. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0829-2.

- Moss, Walter G. (1 July 2003). A History of Russia Volume 1: To 1917. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-0-85728-752-6.

- Plokhy, Serhii (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (PDF). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–15. ISBN 978-0-521-86403-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Rybakov, Boris (1998). Памятники Куликовского цикла [Literary Works of the Kulikovo Cycle] (in Russian). St. Petersburg: Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. ISBN 5-8678-9-033-3.

- Parppei, Kati (2017). The Battle of Kulikovo Refought: "The First National Feat". Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-33794-7.