Battle on the Ice

The Battle on the Ice,[lower-alpha 1] alternatively known as the Battle of Lake Peipus (German: Schlacht auf dem Peipussee; Russian: битва на Чудском озере), took place on 5 April 1242. It was fought largely on the frozen Lake Peipus between the united forces of the Republic of Novgorod and Vladimir-Suzdal, led by Prince Alexander Nevsky, and the forces of the Livonian Order and Bishopric of Dorpat, led by Bishop Hermann of Dorpat.

| Battle on the Ice | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Northern Crusades and the Livonian campaign against Rus' | |||||||

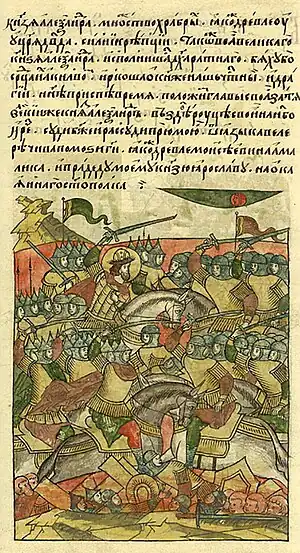

Depiction of the battle in the late 16th century illuminated manuscript Life of Alexander Nevsky | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hermann of Dorpat Andreas von Velven |

Alexander Nevsky Andrey Yaroslavich | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2,600:[1]

|

5,000:[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Livonian Rhymed Chronicle: 50 Germans imprisoned "Countless" Estonians killed[3] | No exact figures | ||||||

The battle was significant because its outcome determined whether Western Catholicism or Eastern Orthodox Christianity would dominate in the region. In the end, the battle represented a significant defeat for the Catholic forces during the Northern Crusades and brought an end to their campaigns against the Orthodox Novgorod Republic and other Russian territories for the next century.[4]

The significance and likely the scale of the battle was exaggerated in later Russian sources, which hailed it as one of the great Russian victories of the Middle Ages.[5] The event portrayed in Sergei Eisenstein's historical drama film, Alexander Nevsky (1938), later created a popular but inaccurate image of the battle.

The Novgorodian victory is commemorated today in Russia as one of the Days of Military Honour.

Background

In 1221, Pope Honorius III was again worried about the situation in the Finnish-Novgorodian Wars after receiving alarming information from the Archbishop of Uppsala. He authorized the Bishop of Finland to establish a trade embargo against the "barbarians" that threatened Christianity in Finland.[6] The nationality of the "barbarians", presumably a citation from Archbishop's earlier letter, remains unknown, and was not necessarily known even by the Pope. However, as the trade embargo was widened eight years later, it was specifically said to be against the Russians.[7] Based on Papal letters from 1229,[8] the Bishop of Finland requested the Pope enforce a trade embargo against Novgorodians on the Baltic Sea, at least in Visby, Riga and Lübeck. A few years later, the Pope also requested the Livonian Brothers of the Sword send troops to protect Finland. Whether any knights ever arrived remains unknown.[9]

In 1237, the Swedes received papal authorization to launch a crusade, and in 1240, new campaigns began in the easternmost part of the Baltic region.[10] After a successful campaign into Tavastia, the Swedes advanced further east until they were stopped by a Novgorodian army led by Prince Alexander Yaroslavich who had defeated the Swedes in the Battle of the Neva in July 1240 and received the nickname Nevsky.[11]

Although the missionaries and Crusaders had attempted to establish peaceful relations with the Novgorod Republic, Livonian missionary and crusade activity in Estonia caused conflicts with Novgorod, who had also attempted to subjugate, raid and convert the pagan Estonians.[12] The Estonians also sometimes attempted to ally with the Russians against the Crusaders, with the eastern Baltic missions constituting a threat to Russian interests and the tributary peoples.[13] In 1240, the combined forces of the exiled prince of Pskov, Yaroslav Vladimirovich, and men from the Bishopric of Dorpat attacked the Pskov Republic and Votia, a tributary of Novgorod.[14][15] This triggered the counterattack from Novgorod in 1241.[16] The delayed response was a result of the internal strife in Novgorod.[17]

Hoping to exploit Novgorod's weakness in the wake of the Mongol and Swedish invasions, the Teutonic Knights attacked the neighboring Novgorod Republic and occupied Pskov, Izborsk, and Koporye in the autumn of 1240.[12] When they approached Novgorod itself, the local citizens recalled to the city 20-year-old Prince Alexander Nevsky, whom they had banished to Pereslavl earlier that year.[18]

In regards to the pagans still living between Pskov and Novgorod and the Latin Christian settlements in Finland, Estonia and Livonia ("the land between christianized Estonia and Russia, meaning Votia, Neva, Izhoria, and Karelia"),[lower-alpha 2] a treaty was concluded in 1241 at Riga between the bishop of Ösel–Wiek and the Teutonic Order, which stipulated that the bishop was granted spiritual superiority in the newly conquered territories.[20] The treaty indicated that the crusaders were well aware of the existence of these pagans.[19]

During the campaign of 1241, Alexander managed to retake Pskov and Koporye from the crusaders,[12][21][22] and executed those local Votians who had worked with the invaders.[17] Alexander then continued into Estonian-German territory.[17] In the spring of 1242, the Teutonic Knights defeated a detachment of the Novgorodian army about 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of the fortress of Dorpat (now Tartu). As a result, Alexander set up a position at Lake Peipus.[17] Led by Prince-Bishop Hermann of Dorpat, the knights and their auxiliary troops of local Ugaunians then met with Alexander's forces on 5 April 1242,[17] by the narrow strait (Lake Lämmijärv or Teploe) that connects the north and south parts of Lake Peipus (Lake Peipus proper with Lake Pskovskoye).

Battle

On 5 April 1242 Alexander, intending to fight in a place of his own choosing, retreated in an attempt to draw the often over-confident Crusaders onto the frozen lake.[18] Estimates on the number of troops in the opposing armies vary widely among scholars. A more conservative estimation has it that the crusader forces likely numbered around 2,600, including 800 Danish and German knights, 100 Teutonic knights, 300 Danes, 400 Germans, and 1,000 Estonian infantry.[2] The Russians fielded around 5,000 men: Alexander and his brother Andrei's bodyguards (druzhina), totalling around 1,000, plus 2,000 militia of Novgorod, 1,400 Finno-Ugrian tribesmen, and 600 allied Turkish horse archers.[2]

The Teutonic knights and crusaders charged across the lake and reached the enemy, but were held up by the infantry of the Novgorod militia.[18] This caused the momentum of the crusader attack to slow. The battle was fierce, with the allied Russians fighting the Teutonic and crusader troops on the frozen surface of the lake. After a little more than two hours of close quarters fighting, Alexander ordered the left and right wings of his army (including cavalry) to enter the battle.[18] The Teutonic and crusader troops by that time were exhausted from the constant struggle on the slippery surface of the frozen lake. The Crusaders started to retreat in disarray deeper onto the ice, and the appearance of the fresh Novgorod cavalry made them retreat in panic.

It is commonly said that "the Teutonic knights and crusaders attempted to rally and regroup at the far side of the lake, however, the thin ice began to give way and cracked under the weight of their heavy armour, and many knights and crusaders drowned"; but Donald Ostrowski writes in his article Alexander Nevskii's "Battle on the Ice": The Creation of a Legend that accounts of ice breaking and knights drowning are a relatively recent embellishment to the original historical story.[23] He cites a large number of scholars who have written about the battle, Karamzin, Solovyev, Petrushevskii, Khitrov, Platonov, Grekov, Vernadsky, Razin, Myakotin, Pashuto, Fennell, and Kirpichnikov, none of whom mention the ice breaking up or anyone drowning when discussing the battle on the ice.[23] After analysing all the sources Ostrowski concludes that the part about ice breaking and drowning appeared first in the 1938 film Alexander Nevsky by Sergei Eisenstein.[23]

Casualties

According to the Livonian Order's Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, written in the late 1340s:

The [Russians] had many archers, and the battle began with their bold assault on the king's men [Danes]. The brothers' banners were soon flying in the midst of the archers, and swords were heard cutting helmets apart. Many from both sides fell dead on the grass. Then the Brothers' army was completely surrounded, for the Russians had so many troops that there were easily sixty men for every one German knight. The Brothers fought well enough, but they were nonetheless cut down. Some of those from Dorpat escaped from the battle, and it was their salvation that they fled. Twenty brothers lay dead and six were captured.[24]

According to the Novgorod First Chronicle:

Prince Alexander and all the men of Novgorod drew up their forces by the lake, at Uzmen, by the Raven's Rock; and the Germans and the Estonians rode at them, driving themselves like a wedge through their army. And there was a great slaughter of Germans and Estonians... they fought with them during the pursuit on the ice seven versts short of the Subol [north-western] shore. And there fell a countless number of Estonians, and 400 of the Germans, and they took fifty with their hands and they took them to Novgorod.[25]

Historical legacy

The legacy of the battle, and its decisiveness, came because it halted the eastward expansion of the Teutonic Order,[26] and established a permanent border line through the Narva River and Lake Peipus dividing Eastern Orthodoxy from Western Catholicism.[27] The knights' defeat at the hands of Alexander's forces prevented the crusaders from retaking Pskov, the linchpin of their eastern crusade. The Novgorodians succeeded in defending Russian territory, and the crusaders never mounted another serious challenge eastward. Alexander was canonised as a saint in the Russian Orthodox Church in 1574.[28]

Some historians have argued that the launch of the campaigns in the eastern Baltic at the same time were part of a coordinated campaign; Finnish historian Gustav A. Donner argued in 1929 that a joint campaign was organized by William of Modena and originated in the Roman Curia.[29] This interpretation was taken up by Russian historians such as Igor Pavlovich Shaskol'skii and a number of Western European historians.[29] More recent historians have rejected the idea of a coordinated attack between the Swedes, Danes and Germans, as well as a papal master plan due to a lack of decisive evidence.[29] Some scholars have instead considered the Swedish attack on the Neva River to be part of the continuation of rivalry between the Russians and Swedes for supremacy in Finland and Karelia.[30] Anti Selart also mentions that the papal bulls from 1240 to 1243 do not mention warfare against Russians, but against non-Christians.[31] Selart also argues that the crusades were not an attempt to conquer Russia, but still constituted an attack on the territory of Novgorod and its interests.[32]

The event was glorified in Sergei Eisenstein's patriotic historical drama film Alexander Nevsky, released in 1938.[33] The movie, bearing propagandist allegories of the Teutonic Knights as Nazi Germans, with the Teutonic infantry wearing modified World War I German Stahlhelm helmets, has created a popular image of the battle often mistaken for the real events.[33] In particular, the image of knights dying by breaking the ice and drowning originates from the film.[23] Sergei Prokofiev turned his score for the film into a concert cantata of the same title, the longest movement of which is "The Battle on the Ice".[34]

During World War II, the image of Alexander Nevsky became a national Russian symbol of the struggle against German occupation.[35] The Order of Alexander Nevsky was re-established in the Soviet Union in 1942 during the Great Patriotic War.[28] Since 2010, the Russian government has given out an Order of Alexander Nevsky (originally introduced by Catherine I of Russia in 1725) given for outstanding bravery and excellent service to the country.

In 1983, a revisionist view proposed by historian John L. I. Fennell argued that the battle was not as important, nor as large, as has often been portrayed. Fennell claimed that most of the Teutonic Knights were by that time engaged elsewhere in the Baltic, and that the apparently low number of knights' casualties according to their own sources indicates the smallness of the encounter.[35] He also says that neither the Suzdalian chronicle (the Lavrent'evskiy), nor any of the Swedish sources mention the occasion, which according to him would mean that the 'great battle' was little more than one of many periodic clashes.[35] Russian historian Alexander Uzhankov suggested that Fennell distorted the picture by ignoring many historical facts and documents. To stress the importance of the battle, he cites two papal bulls of Gregory IX, promulgated in 1233 and 1237, which called for a crusade to protect Christianity in Finland against her neighbours. The first bull explicitly mentions Russia. The kingdoms of Sweden, Denmark and the Teutonic Order built up an alliance in June 1238, under the auspices of the Danish king Valdemar II. They assembled the largest western cavalry force of their time. Another point mentioned by Uzhankov is the 1243 treaty between Novgorod and the Teutonic Order, where the knights abandoned all claims to Russian lands. Uzhankov also emphasizes, with respect to the scale of battle, that for each knight deployed on the field there were eight to 30 combatants, counting squires, archers and servants (though at his stated ratios, that would still make the Teutonic losses number at most a few hundred).[36]

Notes

References

- "Histoire Russe." Volume 33. University Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh, 2006. p. 300.

- Nicolle, David (1996). Lake Peipus 1242: Battle of the Ice. Osprey Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 9781855325531.

- The Chronicle of Novgorod (PDF). London. 1914. p. 87.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2003. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 218, ...later to become hailed as one of the great Russian victories of the Middle Ages... scale of the battle was, however, most likely exaggerated in the later Russian sources, as was indeed its significance.

- "Letter by Pope Honorius III to the Bishop of Finland". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. in 1221. In Latin.

- See papal letters from 1229 to "Riga". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. and "Lübeck". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.. In Latin.

- See letters by Pope Gregory IX: , , , , , , . All in Latin.

- "Letter by Pope Gregory IX". Archived from the original on 2007-08-14.. In Latin.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 216–217, The Russian victory was later depicted as an event of great national importance and Prince Alexander was given the sobriquet "Nevskii".

- Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia, 980–1584. Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–219. ISBN 9780511811074.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 216, The missions in the eastern Baltic constituted a threat to the Russians of Novgorod and Pskov, their tributary peoples and their interests in the region.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 220, The campaigns to the River Neva and into Votia were... crusades aiming at expanding the Catholic Church... the campaign against Izborsk and Pskov was a purely political undertaking... the co-operation between the exiled Prince Yaroslav Vladimirovich of Pskov and the men from the bishopric of Dorpat.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 218, In the winter of 1240–41, a group of Latin Christians invaded Votia, the lands north-east of Lake Peipus which were tributary to Novgorod.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 218, The Novgorodian counterattack came in 1241.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 218.

- Hellie, Richard (2006). "Alexander Nevskii's April 5, 1242 Battle on the Ice". Russian History. 33 (2/4): 284. doi:10.1163/187633106X00177. JSTOR 24664445 – via JSTOR.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 220.

- Murray 2017, p. 164.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 218, After pleas from Novgorod Alexander returned in 1241 and marched against Kopor'e. Having conquered the fortress and captured the remaining Latin Christians, he executed those local Votians who had cooperated with the invaders.

- Murray 2017, p. 164, These conquests were lost in 1241–42, when the Russians destroyed Kopor'e.

- Ostrowski, Donald (2006). "Alexander Nevskii's "Battle On the Ice": the Creation of a Legend". Russian History. 33 (2–4): 289–312. doi:10.1163/187633106x00186. ISSN 0094-288X.

- Urban, William L. (2003). The Teutonic Knights: A Military History. Greenhill. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-85367-535-5.

- Christiansen, Eric (4 December 1997). The Northern Crusades. Penguin UK. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-14-193736-6.

- Riley-Smith Jonathan Simon Christopher. The Crusades: a History, US, 1987, ISBN 0300101287, p. 198.

- Hosking, Geoffrey A. Russia and the Russians: a history, US, 2001, ISBN 0674004736, p. 65.

- "Encyclopedia Britannica | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 219.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 219, some scholars therefore regard the Swedish attack on the River Neva as merely a continuation of the Russo-Swedish rivalry.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 219–220, Selart stresses, none of the papal bulls of 1240–43 mention warfare against the Russians. They only refer to the fight against non-Christians and to mission among pagans.

- Selart, Anti (2001). "Confessional Conflict and Political Co-operation: Livonia and Russia in the Thirteenth Century". Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier 1150–1500. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-25880-5.

- "Alexander Nevsky and the Rout of the Germans". The Eisenstein Reader: 140–144. 1998. doi:10.5040/9781838711023.ch-014. ISBN 9781838711023.

- Danilevsky, Igor (22 May 2015). Ледовое побоище (in Russian). Postnauka. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- John Fennell, The Crisis of Medieval Russia 1200–1304, (London: Longman, 1983), 106.

- Александр Ужанков. Меж двух зол. Исторический выбор Александра Невского (Alexander Uzhankov. Between two evils. The historical choice of Alexander Nevsky) (in Russian)

Bibliography

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt, Iben (2007). The popes and the Baltic crusades, 1147–1254. Brill. ISBN 9789004155022.

- Murray, Alan V. (5 July 2017). Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier 1150–1500. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-94715-2.

Further reading

- Military Heritage did a feature on the Battle of Lake Peipus and the holy Knights Templar and the monastic knighthood Hospitallers (Terry Gore, Military Heritage, August 2005, Volume 7, No. 1, pp. 28–33), ISSN 1524-8666.

- Basil Dmytryshyn, Medieval Russia 900–1700. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1973.

- John France, Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades 1000–1300. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999.

- Donald Ostrowski, "Alexander Nevskii's ‘Battle on the Ice’: The Creation of a Legend,” Russian History/Histoire Russe, 33 (2006): 289–312.

- Terrence Wise, The Knights of Christ. London: Osprey Publishing, 1984.

- Dittmar Dahlmann Der russische Sieg über die „teutonischen Ritter“ auf dem Peipussee 1242. In: Gerd Krumeich, Susanne Brandt (ed.): Schlachtenmythen. Ereignis–Erzählung–Erinnerung. Böhlau, Köln/Wien 2003, ISBN 3412087033, pp. 63–75. (in German)

- Livländische Reimchronik. Mit Anmerkungen, Namenverzeichnis und Glossar. Ed. Leo Meyer. Paderborn 1876 (Reprint: Hildesheim 1963). (in German)

- Anti Selart. Livland und die Rus' im 13. Jahrhundert. Böhlau, Köln/Wien 2012, ISBN 9783412160067. (in German)

- Anti Selart. Livonia, Rus’ and the Baltic Crusades in the Thirteenth Century. Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2015.

- Kaldalu, Meelis; Toots, Timo, Looking for the Border Island. Tartu: Damtan Publishing, 2005. Contemporary journalistic narrative about an Estonian youth attempting to uncover the secret of the Ice Battle.

- Joseph Brassey, Cooper Moo, Mark Teppo, Angus Trim, "Katabasis (The Mongoliad Cycle Book 4)" 47 North, 2013 ISBN 1477848215

- David Savignac, The Pskov 3rd Chronicle, entries under the years 1240–1242, Accessible at https://www.academia.edu/28622167/The_Pskov_3rd_Chronicle