Novgorod Republic

The Novgorod Republic (Russian: Новгородская республика) was a medieval state that existed from the 12th to 15th centuries in northern Russia, stretching from the Gulf of Finland in the west to the northern Ural Mountains in the east. Its capital was the city of Novgorod. The republic prospered as the easternmost trading post of the Hanseatic League, and its people were much influenced by the culture of the Byzantines.[4]

Lord Novgorod the Great | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1136–1478 | |||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Flag (c. 1385)

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms

(c. 1385) | |||||||||||||

Sign on Novgorod's seal (1426): | |||||||||||||

The Novgorod Republic c. 1400 | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Novgorod | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Church Slavonic (literary)[1] Old Novgorod dialect[lower-alpha 1][2][3] | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodoxy | ||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Novgorodian | ||||||||||||

| Government | Mixed republic | ||||||||||||

| Prince | |||||||||||||

• 1136–1138 (first) | Sviatoslav Olgovich | ||||||||||||

• 1462–1478 (last) | Ivan III | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Veche Council of Lords | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 1136 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1478 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Russia | ||||||||||||

| History of Russia |

|---|

|

|

|

Name

The state was called Novgorod and Great Novgorod (Russian: Великий Новгород, romanized: Veliky Novgorod) with the form Sovereign Lord Novgorod the Great (Russian: Государь Господин Великий Новгород, romanized: Gosudar Gospodin Veliky Novgorod) becoming common in the 15th century. Novgorod Land and Novgorod volost usually referred to the land belonging to Novgorod. Novgorod Republic itself is a much later term,[5] although the polity was described as a republic as early as in the beginning of the 16th century.[6][7] Soviet historians frequently used the terms Novgorod Feudal Republic and Novgorod Boyar Republic.[8]

History

Novgorod was populated by various Slavic tribes that were constantly at war with one another for supremacy. However, these tribes came together during the beginning of the 9th century to try to form a negotiated settlement to end military aggression amongst each other.[9] The Novgorod First Chronicle, a collection of writings depicting the history of Novgorod from 1016 to 1471, states that these tribes wanted to "Seek a prince who may rule over us and judge us according to law."[10] Novgorodian Rus' and its inhabitants were influenced by Vikings.[11]

Novgorod Republic

From the late 11th century Novgorodians asserted greater control over the determination of their rules and rejected a politically dependent relationship to Kiev.[12]

Among the Rus, the Novgorodians were the first to reach the regions between the Arctic Ocean and Lake Onega. Even though there is no definitive account of the precise timing of their arrival at the northern rivers that flowed into the Arctic, there are chronicles which mention that one expedition reached the Pechora River in 1032, and trading was established as early as in 1096 with the Yugra tribe.[13]

Chronicles also stated that the Novgorodians paid tribute to the Prince of Kiev by 1113. Some time after this, the administration of the principality seemed to have matured. The Novgorod tysiatskii and posadniki appointed boyars from the cities and collected revenues for administration in the territories it held. A charter from the 1130s mentioned 30 administrative posts in Novgorod territory, where revenues were collected regularly and sent as a tithe to the Novgorod bishop. Throughout the 12th century, Novgorod utilized the Baltic-Volga-Caspian trade route, not only for trading but also for bringing food from the fertile Oka region to their city.[13]

Rostov-Suzdal comprised the territory of the important Oka region and lands along the vital Sheksna River. This river lay in the Northern Volga tributary region. Whoever controlled the river was able to block food supplies causing a famine in Novgorod. Perhaps due to these fears, Novgorod led a failed invasion of Suzdal in 1134. They tried again and succeeded in 1149. Alternatively, Novgorod, in a bid to appease Suzdal, accepted some Suzdalians as rulers of Novgorod. Despite these events, Suzdal still blocked off trade to Novgorod twice and intercepted Novgorod's tributes.[13]

In 1136, the Novgorodians dismissed Prince Vsevolod Mstislavich and over the next century and a half were able to invite in and dismiss a number of princes. However, these invitations or dismissals were often based on who was the dominant prince in Rus' at the time, and not on any independent thinking on the part of Novgorod.[14]

The city of Pskov, initially part of Novgorod Land, had de facto independence from as early as the 13th century after opening a trading post for merchants of the Hanseatic League. Several princes such as Vsevolod Mstislavich (before 1117–1138) and Dovmont (c. 1240–1299) reigned in Pskov without any deference to, or consultation with, the prince or other officials in Novgorod. The independence of the Pskov Republic was acknowledged in the 1348 Treaty of Bolotovo. However, the Archbishop of Novgorod continued to head the church in Pskov and kept the title "Archbishop of Novgorod the Great and Pskov" until 1589. The Republic was the subject of political rivalry between Poland and Lithuania on one side and the Grand Duchy of Moscow on the other side in the 14th and 15th centuries.

In the 12th–15th centuries, the Novgorodian Republic expanded east and northeast. The Novgorodians explored the areas around Lake Onega, along the Northern Dvina, and coastlines of the White Sea. At the beginning of the 14th century, the Novgorodians explored the Arctic Ocean, the Barents Sea, the Kara Sea, and the West-Siberian river Ob. The lands to the north of the city, rich with fur, sea fauna and salt among others were of great economic importance to the Novgorodians, who fought a protracted series of wars with Moscow beginning in the late 14th century in order to keep these lands. Losing them meant economic and cultural decline for the city and its inhabitants. Indeed, the ultimate failure of the Novgorodians to win these wars led to the downfall of the Novgorod Republic.

Fall of the Republic

Tver, Muscovy, and Lithuania fought over control of Novgorod and its enormous wealth from the 14th century. Upon becoming the Grand Prince of Vladimir, Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tver sent his governors to Novgorod. A series of disagreements with Mikhail pushed Novgorod towards closer ties with Muscovy during the reign of Grand Prince George. In part, Tver's proximity (the Tver Principality is contiguous with the Novgorodian Land) threatened Novgorod. It was feared that a Tverite prince would annex Novgorodian lands and thus weaken the Republic. At the time, though, Muscovy did not border Novgorod, and since the Muscovite princes were further afield, they were more acceptable as princes of Novgorod. They could come to Novgorod's aid when needed but would be too far away to meddle too much in the Republic's affairs.

As Muscovy grew in strength, however, the Muscovite princes became a serious threat to Novgorod. Ivan Kalita, Simeon the Proud and other Muscovite monarchs sought to limit Novgorod's independence. In 1397, a critical conflict took place between Muscovy and Novgorod, when Moscow annexed the Dvina Lands along the course of the Northern Dvina. These lands were crucial to Novgorod's well-being since much of the city's furs came from there.[15][16] This territory was returned to Novgorod the following year.

Resisting the Muscovite oppression, the government of Novgorod sought an alliance with Poland–Lithuania. Most Novgorodian boyars wished to maintain the Republic's independence since if Novgorod were to be conquered, the boyars' wealth would flow to the grand prince and his Muscovite boyars, and the Novgorodians would fall into decline. Most of them didn't earn enough to pay for war.[17] According to tradition, Marfa Boretskaya, the wife of Posadnik Isak Boretskii, was the main proponent of an alliance with Poland-Lithuania to save the Republic.

According to this legend, Boretskaya invited the Lithuanian princeling Mikhail Olelkovich and asked him to become her husband and the ruler of Novgorod. She also concluded an alliance with Casimir, the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. The prospects of changing allegiance in favor of the allied Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania caused a major commotion among the commoners. Janet Martin and Gail Lenhoff have recently argued that Boretskaya was scapegoated, probably by Archbishop Feofil (r. 1470–1480) in order to shift the blame from him for his betrayal of the terms of the Treaty of Yazhelbitsy, which forbade Novgorod from conducting foreign affairs without grand princely approval.[18]

While the extent of Boretskaya's role in the Lithuanian party is probably exaggerated, Novgorod did indeed try to turn to the King of Poland. A draft treaty, allegedly found among the loot after the Battle of Shelon River, was drawn up between Casimir and the Novgorodians.[19]

Muscovite authorities saw Novgorod's behavior as a repudiation of the Treaty of Yazhelbitsy and went to war against the city. The army of Moscow won a decisive victory in the Battle of Shelon River on July 1471, which severely limited Novgorod's freedom to act thereafter, although the city maintained its formal independence for the next seven years. In 1478, Ivan III sent his army to take the city. He destroyed the veche, tore down the Veche bell, the ancient symbol of participatory governance, civil society, and legal rights, and destroyed the library and archives, thus ending the independence of Novgorod.[20] After the takeover, Ivan took 81.7% of Novgorod's land, half for himself and the rest for his allies.[21] The Novgorod Chronicle which had been critical of Ivan III before the fall of Novgorod thus described the conquest in its aftermath, justifying it on the grounds of purported conversion of Novgorodians to the Catholic faith:[22]

Thus did Great Prince Ivan advance with all his host against his domain of Novgorod because of the rebellious spirit of its people, their pride and conversion to Latinism. With a great and overwhelming force did he occupy the entire territory of Novgorod from frontier to frontier, inflicting on every part of it the dread powers of his fire and sword.

Government

The city state of Novgorod had developed procedures of governance that held a large measure of democratic participation far in advance of the rest of Europe[23] but that share several similarities with the democratic traditions of Scandinavian peasant republics. The people had the power to elect city officials and they even had the power to elect and fire the prince. The Chronicle writer then goes on to describe a "town meeting" where these decisions would have been made, which included people from all social classes ranging from the Posadniki (Burgomaster), to the Chernye Liudi (literally, the black folks) or the lowest free class.[24][25] The precise constitution of the medieval Novgorodian Republic is uncertain, although traditional histories have created the image of a highly institutionalized network of veches (public assemblies) and a government of posadniks (burgomaster), tysyatskys ("thousandmen," originally the head of the town militia, but later a judicial and commercial official), other members of aristocratic families, and the archbishops of Novgorod.

Novgorod was called a republic by Sigismund von Herberstein in his Notes on Muscovite Affairs written at least half a century after the conquest of Novgorod.[6]

Soviet-era Marxist scholarship frequently described the political system of Novgorod as a "feudal republic", placing it within the Marxist historiographic periodization (slavery – feudalism – capitalism – socialism – communism).[26][27] Many scholars today, however, question whether Russia ever really had a feudal political system parallel to that of the medieval West.

Archbishop

Some scholars argue that the archbishop was the head of the executive branch of the government, although it is difficult to determine the exact competence of the various officials. It is possible that there was a "Council of Lords" (Совет Господ) that was headed by the archbishop and met in the archiepiscopal palace (and in the Chamber of Facets after 1433).[28][29]

The (at least nominal) executives of Novgorod were always the Princes of Novgorod, invited by Novgorodians from the neighboring states, even though their power waned in the 13th and early 14th centuries.[30][31] It is unclear if the archbishop of Novgorod was the real head of state or chief executive of the Novgorod Republic, but in any case he remained an important town official. In addition to overseeing the church in Novgorod, he headed embassies, oversaw certain court cases of a secular nature, and carried out other secular tasks. However, the archbishops appear to have worked with the boyars to reach a consensus and almost never acted alone. The archbishop was not appointed, but elected by Novgorodians, and approved by the Metropolitan bishop of Russia.[30] The archbishops were probably the richest single land-owners in Novgorod, and they also made money off court fees, fees for the use of weights and measures in the marketplace, and through other means.[32][33]

Veche and posadnik

by Vasily Khudyakov

Another important executive was the Novgorod Posadnik, who chaired the veche, co-chaired courts together with the Prince, oversaw tax collection and managed current affairs of the city. Most of the Prince's major decisions had to be approved by the Posadnik. In the mid-14th century, instead of one Posadnik, the Veche began electing six. These six posadniks kept their status for their lifetimes, and each year elected among themselves a chief Stepennoy Posadnik. Posadniks were almost invariably members of boyars – the city's highest aristocracy.[34] The precise makeup of the veche is also uncertain, although it appears to have comprised members of the urban population, as well as of the free rural population. Whether it was a democratic institution or one controlled by the boyars has been hotly debated. The posadniks, tysiatskys, and even the bishops and archbishops of Novgorod[35] were often elected or at least approved by the veche.[36]

Tradespeople and craftsmen also participated in the political affairs of Novgorod the Great. The traditional scholarship argues that they were organized into five "kontsy" ("ends" in Russian) – i.e., the boroughs of the city they lived in; each end was then organized by the streets in which they lived. The ends and streets often bore names indicating that certain trades were concentrated in certain parts of the city (there was a Carpenter's End and a Potters' End, for example). The merchants were organised into associations, of which the most famous were those of wax traders (called Ivan's Hundred) and of the merchants engaged in overseas trade.[37]

.png.webp)

Like much of the rest of Novgorod's medieval history, the precise composition of these organizations is uncertain. It is quite possible that the "ends" and "streets" were simply neighborhood administrative groups rather than guilds or "unions". Street organizations were known to build churches in their neighborhoods and to have buried the dead of their neighborhoods during outbreaks of the plague, but beyond that their activities are uncertain.

"Streets" and "ends" may have taken part in political decision-making in Novgorod in support of certain boyar factions or to protect their interests. Merchant "elders" are also noted in treaties and other charters, but only about a hundred of these charters exist. A half dozen date from the 12th century, while most are from after 1262. Thus it is difficult to determine Novgorod's political structure due to the paucity of sources.[38]

Prince

The prince, while his status in Novgorod was not inheritable and his power was much reduced, remained an important figure in Novgorodian life. Of around 100 princes of Novgorod, many, if not most, were invited in or dismissed by the Novgorodians. At least some of them signed a contract called a r'ad (ряд), which protected the interests of the Novgorodian boyars and laid out the prince's rights and responsibilities. The r'ads that have been preserved in archives describe the relationship of Novgorod with twelve invited Princes: five of them from Tver', four from Moscow, and three from Lithuania.[39]

First and foremost among the prince's functions, he was a military leader. He also patronized churches in the city and held court, although it was often presided over by his namestnik or lieutenant when he was personally absent from the city. The posadnik had always to be present in the court and no court decision could be made without his approval. Also, without the posadnik's approval the prince could neither give out Novgorod lands nor issue laws.[40] Besides, the prince could not own land in Novgorod and could not himself collect taxes from the Novgorod lands. He lived from money given to him by the city.[30]

According to several r'ads, the prince could not extradite or prosecute a Novgorodian outside of the Novgorodian Land.[41] The princes had two residences, one on the Marketplace (called Yaroslav's Court, after Yaroslav the Wise), and another (Городище / Riurkovo Gorodische) several miles south of the Market Side of the city.

Administrative divisions

The administrative division of Novgorod Republic is not definitely known; the country was divided into several tysyachas (Russian: тысячи, lit. 'thousands') in the core lands of the country, and volosts (Russian: волости) in lands in the east and north that were being colonised or just paid tribute. The city of Novgorod and its vicinity, as well as a few other towns, were not part of any of those. Pskov achieved autonomy from Novgorod in the 13th century; its independence was confirmed by the Treaty of Bolotovo in 1348. Several other towns had special status as they were owned jointly by Novgorod and one of the neighbouring states.

Economy

by Apollinary Vasnetsov.

The economy of the Novgorodian Republic included farming and animal husbandry (e.g., the archbishops of Novgorod and others raised horses for the Novgorodian army), while hunting, beekeeping, and fishing were also widespread. In most of the regions of the republic, these different "industries" were combined with farming. Iron was mined on the coast of the Gulf of Finland. Staraya Russa and other localities were known for their saltworks. Flax and hop cultivation were also of significant importance. Countryside products, such as furs, beeswax, honey, fish, lard, flax, and hops, were sold on the market and exported to other Russian cities or abroad.

The real wealth of Novgorod, however, came from the fur trade. The city was the main entrepôt for trade between Rus' and northwestern Europe as it was located at the eastern end of the Baltic trade network established by the Hanseatic League. From Novgorod's northeastern lands ("The Lands Beyond the Portages" as they were called in the chronicles), the area stretching north of Lakes Ladoga and Onega up to the White Sea and east to the Ural Mountains[42] had so much fur that medieval travel accounts tell of furry animals raining from the sky.[43] The Novgorodian merchants traded with Swedish, German, and Danish cities. In early years, the Novgorodians sailed the Baltic themselves (several incidents involving Novgorodian merchants in Gotland and Denmark are reported in the Novgorodian First Chronicle). Orthodox churches for Novgorodian merchants have been excavated on Gotland. Likewise, merchants from Gotland had their own St. Olaf church and trading house in Novgorod. However the Hanseatic League disputed the right of the Novgorod merchants to carry out sea trade independently and to deliver cargoes to the West-European ports by their own ships. Silver, cloth, wine and herring were imported from Western Europe.[37]

Foreign coins and silver were used as a currency before Novgorod started minting its own novgorodka coins in 1420.[44][45]

Society

More than a half of all Novgorodian privately owned lands had been concentrated in the hands of some 30–40 noble boyar families by the 14th–15th century. These vast estates served as material resources, which secured political supremacy of the boyars. The House of Holy Wisdom (Дом святой Софии, Dom Svyatoy Sofiy) – the main ecclesiastic establishment of Novgorod – was their chief rival in terms of landownership. Its votchinas were located in the most economically developed regions of the Novgorod Land. The Yuriev Monastery, Arkazhsky Monastery, Antoniev Monastery and some other privileged monasteries are known to have been big landowners. There were also the so-called zhityi lyudi (житьи люди), who owned less land than the boyars, and unprivileged small votchina owners called svoyezemtsy (своеземцы, or private landowners). The most common form of labor exploitation – the system of metayage – was typical for the afore-mentioned categories of landowners. Their household economies were mostly serviced by slaves (kholopy), whose number had been constantly decreasing. Along with the metayage, monetary payments also gained significant importance by the 2nd half of the 15th century.

Some scholars argue that the feudal lords tried to legally tie down the peasants to their land. Certain categories of feudally dependent peasants, such as davniye lyudi (давние люди), polovniki (половники), poruchniki (поручники), dolzhniki (должники), were deprived of the right to leave their masters. The boyars and monasteries also tried to restrict other categories of peasants from switching their feudal lords. However, until the late 16th century peasants could leave their land in the weeks preceding and coming after St. George's day in the autumn.

Marxist scholars (e.g., Aleksandr Khoroshev) often spoke of class struggle in Novgorod. There were some 80 major uprisings in the republic, which often turned into armed rebellions. The most notable among these took place in 1136, 1207, 1228–29, 1270, 1418, and 1446–47. The extent to which these were based on "class struggle" is unclear. Many were between various boyar factions or, if a revolt did involve the peasants or tradesmen against the boyars, it did not consist of the peasants wanting to overthrow the existing social order, but was more often than not a demand for better rule on the part of the ruling class. There did not seem to be a sense that the office of prince should be abolished or that the peasants should be allowed to run the city.

Throughout the republican period, the archbishop of Novgorod was the head of the Orthodox church. The Finnic population of the Novgorod land was undergoing Christianisation. The sect of Strigolniki spread to Novgorod from Pskov in the middle of 14th century, its members renouncing ecclesiastic hierarchy, monasticism and sacraments of priesthood, communion, repentance and baptism. Another sect, called the heresy of the Judaizers by its opponents appeared in Novgorod in the second half of 15th century and subsequently enjoyed support at the court in Moscow.

Military

Similar to other medieval states in Rus', the military of Novgorod consisted of a levy and the prince's retinue (druzhina).[46] While potentially all free Novgorodians could be mobilised, in reality the number of recruits depended on the level of danger faced by Novgorod. The professional formations included the retinues of the archbishop and prominent boyars, as well as the garrisons of fortresses.[47] Firearms were first mentioned in 1394[48] and in the 15th century fortress artillery was used[49] and cannons were installed on ships.[50]

Foreign relations

During the era of Kievan Rus', Novgorod was a trade hub at the northern end of both the Volga trade route and the "route from the Varangians to the Greeks" along the Dnieper river system. A vast array of goods were transported along these routes and exchanged with local Novgorod merchants and other traders. The merchants of Gotland retained the Gothic Court trading house well into the 12th century. Later German merchantmen also established tradinghouses in Novgorod. Scandinavian royalty would intermarry with Russian princes and princesses.

Hansa, Sweden and Livonian Order

After the great schism, Novgorod struggled from the beginning of the 13th century against Swedish, Danish, and German crusaders. During the Swedish–Novgorodian Wars, the Swedes invaded lands where some of the population had earlier paid tribute to Novgorod. The Germans had been trying to conquer the Baltic region since the late 12th century. Novgorod went to war 26 times with Sweden and 11 times with the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. The German knights, along with Danish and Swedish feudal lords, launched a series of uncoordinated attacks in 1240–1242. Novgorodian sources mention that a Swedish army was defeated in the Battle of the Neva in 1240. The Baltic German campaigns ended in failure after the Battle on the Ice in 1242. After the foundation of the castle of Vyborg in 1293 the Swedes gained a foothold in Karelia. On August 12, 1323, Sweden and Novgorod signed the Treaty of Nöteborg, regulating their border for the first time.

Mongol invasion and its aftermath

The Novgorod Republic was saved from the direct impact of the Mongol invasion as it was the only Rus principality that was never conquered by the Mongol troops.[51] In 1259, Mongol tax-collectors and census-takers arrived in the city, leading to political disturbances and forcing Alexander Nevsky to punish a number of town officials (by cutting off their noses) for defying him as Grand Prince of Vladimir (soon to be the khan's tax-collector in Russia) and his Mongol overlords. In the 14th century, raids by Novgorod pirates, or ushkuiniki,[52] sowed fear as far as Kazan and Astrakhan, assisting Novgorod in wars with Muscovy.

Culture

Art and iconography

The Republic of Novgorod was famous for its high level of culture in relation to other Russian duchies like Suzdal. A great majority of the most important Eastern artwork of the period came from this city. Citizens of Novgorod were producing large quantities of art, more specifically, religious icons. This high level of artistic production was due to the flourishing economy. Not only would prominent boyar families commission the creation of icons, but artists also had the backing of wealthy merchants and members of the strong artisan class.[53] Icons became so prominent in Novgorod that by the end of the 13th century a citizen did not have to be particularly rich to buy one; in fact, icons were often produced as exports as well as for churches and homes.[54] However, scholars today have managed to find and preserve only a small, random assortment of icons made from the 12th century to the 14th century in Novgorod.[54]

The icons that do remain show a mixture of traditional Rus style, Palaeologus-Byzantine style (prominent previously in Kiev), and European Romanesque and Gothic style.[55] The artists of Novgorod, and their audience, favored saints who provided protection mostly related to the economy. The Prophet Elijah was the lord of thunder who provided rain for the peasants' fields. Saint George, Saint Blaise, and Saints Florus and Laurus all provided some manner of protection over the fields or the animals and herds of the peasants. Saint Paraskeva Pyatnitsa and Saint Anastasia both protected trade and merchants. Saint Nicholas was the patron of carpenters and protected travelers and the suffering. Both Saint Nicholas and the Prophet Elijah also offer protection from fires. Fires were commonplace in the fields and on the streets of the city.[56] Depictions of these saints retained popularity throughout the entire reign of the Republic. But in the beginning of the 14th century another icon became prominent in the city: the Virgin of Mercy. This icon commemorates the appearance of the Virgin Mary to Andrew Yurodivyi and Epifanii. During this appearance, Mary prays for humankind.[57] The art movement of Novgorod was essentially destroyed by Moscow after 1478, when a more uniform method for iconography was established throughout Russia.[58]

Architecture and city layout

The Volkhov River divided the Republic of Novgorod into two-halves. The commercial side of the city, which contained the main market, rested on one side of the Volkhov. The St. Sophia Cathedral and an ancient kremlin rested on the other side of the river.[59] The cathedral and kremlin were surrounded by a solid ring of city walls, which included a bell tower. Novgorod was filled with and surrounded by churches and monasteries.[60] The city was overcrowded because of its large population of 30,000 people. The wealthy (boyar families, artisans, and merchants) lived in large houses inside the city walls, and the poor used whatever space they could find.[59] The streets were paved with wood and were accompanied by a wooden water-pipe system, a Byzantine invention to protect against fire.[59]

The Byzantine style (famous for large domes) and the European Romanesque style influenced the architecture of Novgorod.[61] A number of rich families commissioned churches and monasteries in the city. About 83 churches, almost all of which were built in stone, operated during this period.[62] Two prominent styles of churches existed in the Republic of Novgorod. The first style consisted of a single apse with a slanted (lopastnyi) roof. This style was standard throughout Russia during this period. The second style, the Novgorodian style, consisted of three apses and had roofs with arched gables. This second style was prominent in the early years of the Republic of Novgorod and also in the last years of the Republic, when this style was revitalized to make a statement against the rising power of Moscow.[63] The inside of the churches contained icons, woodcarvings, and church plates.[64] The first known one-day votive church was built in Novgorod in 1390 to ward off a pandemic, several others were built in the city until mid-16th century. As they were built in one day, they were made of wood, small in size and simple in design.[65][66]

Literature and literacy

Chronicles are the earliest kind of literature known to originate in Novgorod, the oldest one being the Novgorod First Chronicle. Other genres appear in the 14th and 15th centuries: travel diaries (such as the account of Stefan the Novgorodian's travel to Constantinople for trade purposes), legends about local posadniks, saints and Novgorod's wars and victories.[67] The events of many bylinas – traditional Russian oral epic poems – take place in Novgorod. Their protagonists include a merchant and adventurer Sadko and daredevil Vasily Buslayev.

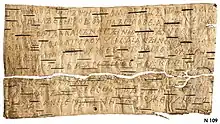

Scholars generally believe that the Republic of Novgorod had an unusually high level of literacy for the time period. Archeologists found over one thousand birch-bark texts, all dating from the 11th to the 15th centuries, in towns dating back to the early Rus'. Roughly 950 of these texts were from Novgorod. Archeologists and scholars estimate that as much as 20,000 similar texts still remain in the ground and many more burned down during numerous fires.[68]

Novgorod citizens from all class levels, from boyars to peasants and artisans to merchants, participated in writing these texts. Even women wrote a significant amount of the manuscripts.[68] This collection of birch-bark texts consists of religious documents, writings from the city's archbishops, business messages from all classes, and travelogues, especially of religious pilgrimages. The citizens of Novgorod wrote in a realistic and businesslike fashion. In addition to the birch-bark texts, archeologists also found the oldest surviving Russian manuscript in Novgorod: three wax tablets with Psalms 67, 75, and 76, dating from the first quarter of the 11th century.[69]

See also

Notes

- Considered to be a dialect of (Old) Russian which dispersed in the 15th century.

References

- The world's heritage : a complete guide to the most extraordinary places. Paris: UNESCO Pub. 2009. p. 383. ISBN 9789231041228.

- Olander, Thomas (2015). Proto-Slavic inflectional morphology : a comparative handbook. Leiden. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9789004270503.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pereltsvaig, Asya (2015). The Indo-European controversy: facts and fallacies in historical linguistics. Cambridge, United Kingdom. pp. 97–98. ISBN 9781107054530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Treadgold, Donald W. (1990). Freedom, a history. Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana (Mississippi State University. Libraries). New York: New York University Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780814781906. OCLC 21901358.

- Lukin, Pavel V. (2018). "Novgorod the Great". Slověne (in Russian). 7 (2): 383–413. doi:10.31168/2305-6754.2018.7.2.15. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- Herberstein, Sigmund von (1851). texts Notes upon Russia : Being a translation of the earliest account of that country, entitled Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii. Hakluyt Society. p. 25.

- Малышев, С. И., ed. (2012). Все град людии, изволеша собе... (in Russian). pp. 12–13. ISBN 9785904062361.

- Igor Froianov, Kievskaia Rus; ocherki sotsialʼno-ekonomicheskoĭ istorii. (Leningrad: Leningrad State University, 1974).

- Sixsmith, Martin (2011). Russia: a 1,000-Year Chronicle of the Wild East. London. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9781446416884.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Primary Chronicle

- RBTH, Elena Potapova (2015-03-11). "On the trail of the Vikings in Veliky Novgorod". www.rbth.com. Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia, 980–1584 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 112–115. ISBN 9780521859165.

- Lantzeff, George V. (1947). "Russian Eastward Expansion before the Mongol Invasion". American Slavic and East European Review. 6 (3/4): 1–5. doi:10.2307/2491696. ISSN 1049-7544. JSTOR 2491696.

- Michael C. Paul, "Was the Prince of Novgorod a 'Third-rate bureaucrat' after 1136?" Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 56, No. 1 (Spring 2008): 72–113.

- Martin, Treasure of the Land of Darkness

- Paul, "Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod Before the Muscovite Conquest," 258–259.

- Richard Pipes, Russia Under the Old Regime, p. 80

- Gail Lenhoff and Janet Martin. "Marfa Boretskaia, Posadnitsa of Novgorod: A Reconsideration of Her Legend and Her Life." Slavic Review 59, no. 2 (2000): 343–368.

- Paul, "Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod," 262.

- Sixsmith, Martin. "Chapter 3." Russia: A 1,000 Year Chronicle of the Wild East. New York: Overlook Pr., 2012. 41. Print.

- Richard Pipes, Russia Under the Old Regime, p. 93

- Sixsmith, Martin. "Chapter 3." Russia: A 1,000 Year Chronicle of the Wild East. New York: Overlook Pr., 2012. 40. Print.

- Sixsmith, Martin. "Chapter 3." Russia: A 1,000 Year Chronicle of the Wild East. New York: Overlook Pr., 2012. 19. Print.

- Sixsmith, Martin. "Chapter 3." Russia: A 1,000 Year Chronicle of the Wild East. New York: Overlook Pr., 2012. 20. Print.

- Ключевский В. О. (Vasily Klyuchevsky) (2004). Русская история: полный курс лекций (in Russian). ОЛМА Медиа Групп. pp. 195–196. ISBN 5948495647.

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto

- See, for example, Igor Froianov, Kievskaia Rus; ocherki sotsialʼno-ekonomicheskoĭ istorii. (Leningrad: Leningrad State University, 1974).

- V. O. Kliuchevskii, Boiarskaia Duma drevnei Rus; Dobrye liudi Drevnei Rus (Moscow: Ladomir 1994), 172–206; Idem., Sochinenii, vol. 2, pp. 68–69

- George Vernadsky, Kievan Rus (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1948), 98, 197–201.

- Valentin Yanin "Outline of history of medieval Novgorod.

- Paul, "Was the Prince of Novgorod a 'Third-rate bureaucrat' after 1136?" passim.

- Michael C. Paul, "Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod Before the Muscovite Conquest." Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 8, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 231–270

- Idem, "Episcopal Election in Novgorod, Rus 1156–1478." Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture 72, no. 2 (June 2003): 251–275.

- Valentin Yanin Novgorod posadniks

- Starting from 1156, elevated to archiepiscopal status in 1165

- Michael C. Paul, "The Iaroslavichi and the Novgorodian Veche 1230–1270: A Case Study on Princely Relations with the Veche," Russian History/ Histoire Russe 31, no. 1–2 (Spring–Summer, 2004): 41.

- Янин, В. Л., ed. (2007). Великий Новгород. Энциклопедический словарь (in Russian). Нестор-История. p. 456. ISBN 9785981872365.

- Valk, ed. Gramoty Velikogo Novgoroda i Pskova

- Valentin Yanin Novgorod acts of 12th–15th centuries

- Valentin Yanin "Sources of Novgorod statehood.

- Paul, "Was the Prince of Novgorod a 'Third-rate bureaucrat' after 1136?" 100–107.

- Janet Martin, Treasure of the Land of Darkness: the Fur Trade and its Significance for Medieval Rus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

- Paul, "Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod Before the Muscovite Conquest," 258.

- Спасский, Иван Георгиевич (1962). Русская монетная система: историко-нумизматический очерк (in Russian). Издательство Государственного Эрмитажа. p. 27.

- Зварич В.В., ed. (1980). "Новгородская денга, новгородка". Нумизматический словарь. Львов: Высшая школа.

- Порфиридов, Н.Г. (1947). Древний Новгород. Очерки из истории русской культуры XI–XV вв (in Russian). Издательство Академии Наук СССР. p. 122.

- Быков, А. В. (2006). Новгородское войско XI–XV веков (диссертация) (in Russian). pp. 83–109.

- Подвальнов Е.Д.; Несин М.А.; Шиндлер О.В (2019). "К вопросу о вестернизации военного дела Северо-Запада Руси". История военного дела: исследования и источники (in Russian). VII: 81. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- Быков, А. В. (2006). Новгородское войско XI–XV веков (диссертация) (in Russian). p. 212.

- Шмелев К.В. (2001). "О применении судовой артиллерии на северо-западе России в допетровское время". Вестник молодых ученых: Исторические науки (in Russian). 1: 53–55.

- Frank McLynn, Genghis Khan (2015), 441.

- Janet Martin, "Les Uškujniki de Novgorod: Marchands ou Pirates." Cahiers du Monde Russe et Sovietique 16 (1975): 5–18.

- Viktor Nikitich Lazarev, Gerolʹd Ivanovich Vzdornov, and Nancy McDarby, The Rus Icon: From Its Origins to the Sixteenth Century (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 1997), 47.

- Lazarev, Vzdornoc, and McDarby, The Rus Icon, 48.

- Anonymous, "Novgorod" in World Heritage: Archaeological Sites and Urban Centres (Paris: Unesco, 2002), 138.

- Lazarev, Vzdornoc, and McDarby, The Rus Icon, 53.

- Lazarev, Vzdornoc, and McDarby, The Rus Icon, 56.

- Lazarev, Vzdornoc, and McDarby, The Rus Icon, 67.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas V.; Steinberg, Mark D. (2019). A History Of Russia. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780190645601.

- Anonymous, "Novgorod," 143.

- Anonymous, "Novgorod," 183.

- V. L. Ianin, "Medieval Novgorod" in The Cambridge History of Russia: From Early Rus' to 1689. Vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008), 208–209.

- Ianin, "Medieval Novgorod ," 209.

- V. K. Laurina and V. A. Puškarev, Novgorod Icons: 12th–17th Century (Leningrad: Aurora, 1980), 21.

- Zguta, Russell (1981). "The One-Day Votive Church: A Religious Response to the Black Death in Early Russia". Slavic Review. 40 (3): 423–432. doi:10.2307/2496195. JSTOR 2496195. PMID 11633170. S2CID 2937303.

- Zelenin, Dmitry (1994). "Обыденные" полотенца и обыденные храмы". Избранные труды. Статьи по духовной культуре 1901–1913 гг (in Russian). Индрик. pp. 208–213. ISBN 5857590078.

- Кусков, Владимир Владимирович (1989). История древнерусской литературы (in Russian). Высшая школа. p. 162.

- Ianin, "Medieval Novgorod," 206.

- Riasanovsky and Steinberg, "Lord Novgorod the Great," 80.