Healthcare in Russia

Healthcare in Russia is provided by the state through the Federal Compulsory Medical Insurance Fund, and regulated through the Ministry of Health.[1] The Constitution of the Russian Federation has provided all citizens the right to free healthcare since 1993. In 2008, 621,000 doctors and 1.3 million nurses were employed in Russian healthcare. The number of doctors per 10,000 people was 43.8, but only 12.1 in rural areas. The number of general practitioners as a share of the total number of doctors was 1.26 percent. There are about 9.3 beds per thousand population—nearly double the OECD average.

Expenditure on healthcare was 6.5% of Gross Domestic Product, US$957 per person in 2013. About 48% comes from government sources which primarily come from medical insurance deductions from salaries. About 5% of the population, mostly in major cities, have voluntary health insurance.[2]

The total population of Russia in 2016 was 146.8 million. Among this population, the number of employed individuals reached 72.3 million, involved in the 99 main types of productive and nonproductive activities.[3] In modern conditions, the world experts estimate the overall health of the Russian working population (men 18–60 years, women 18–55 years) to be rather low due to the high mortality rate, significantly higher male mortality level, and a high prevalence of major noncommunicable diseases, especially those of the circulatory, respiratory, and digestive system. According to official government statistics, 1 of every 3 workers in Russia is exposed to harmful working conditions in which the levels of exposure in the workplace exceed the national hygienic standards. However, the level of occupational morbidity in Russia remains extremely low. In 2014, only 8175 cases of occupational diseases were reported, representing 5.5 cases per 100,000 in the general population, a rate much less than in many European countries.[4]

After the end of the Soviet Union, Russian healthcare became composed of state and private systems. Drastic cuts in funding to the state-run healthcare system brought declines in the quality of healthcare it provided. This made pricier private facilities competitive by marketing themselves as providing better-quality healthcare. After Boris Yeltsin resigned, privatization was no longer the priority, with Vladimir Putin bringing back higher funding to the state-owned healthcare system. The state healthcare system greatly improved throughout the 2000s, with health spending per person rising from $96 in 2000 to $957 in 2013.

Due to the Russian financial crisis since 2014, major cuts in health spending have resulted in a decline in the quality of service of the state healthcare system. About 40% of basic medical facilities have fewer staff than they are supposed to have, with others being closed down. Waiting periods for treatment have increased, and patients have been forced to pay for more services that were previously free.[5][6]

History

Tsarist era

The Medical Sanitary Workers Union was founded in 1820. Vaccination against smallpox was compulsory for children from 1885.[7] The Russian Pharmacy Society for Mutual Assistance was founded in 1895.[8]

Some aspects of the healthcare conditions in Tsarist Russia have been considered "appalling".[9] In 1912, an interdepartmental commission concluded that 'a vast part of Russia has as yet absolutely no provisions for medical aid'.[10] The All Russia League of Struggle Against Venereal Disease estimated that there were 1.5 million sufferers in 1914.[11] 10% of those recruited to the army had tuberculosis.[12] Expenditure on healthcare at that time amounted to 91 kopeks per head of population. There were ten factories in Moscow with their own small hospital in 1903 and 274 had medical personnel on their site. From 1912 legislation encouraged the establishment of contributory hospital schemes. Before 1914 most medical supplies, dressings, drugs, equipment and instruments had been imported from Germany. During the war mortality of the injured was very high. Most died from sepsis but more than 16% from typhus.[13] As many as 10,000 doctors conscripted to the army died between 1914 and 1920.

However, in the field of school hygiene, tsarist Russia surpassed its Western neighbors in the development and implementation of school hygiene measures to protect the health of children in the nation’s schools. By 1900, Russia had endowed school doctors with more authority over school buildings and children’s bodies than in France, Germany and United Kingdom, and the United States.[14]

Early Soviet period

The Bolsheviks announced in 1917 requirements for "comprehensive sanitary legislation", clean water supply, national canalisation and sanitary supervision over commercial and industrial enterprises and residential housing.[15] The All—Russia Congress of Nurses Union, founded in 1917, in 1918 had 18,000 members in 56 branches.[16] The People's Commissariat of Labour announced a broad and comprehensive list of benefits to be covered by social insurance funds in October 1917, including accident and sickness, health care, and maternity leave, but funding intended to come from employers was not available.[17] By December 1917 benefits were restricted to wage earners. Social insurance was re-organised as a five-tier sickness- and accident-benefit scheme which in principle included healthcare and medical treatment by October 1918. Ongoing problems in collecting contributions from employers continued at least until 1924.

In 1918 the Commissariat of Public Health was established.[18] A Council of Medical Departments was set up in Petrograd. Nikolai Semashko was appointed People's Commissar of Public Health of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and served in that role from 11 July 1918 until 25 January 1930. It was to be "responsible for all matters involving the people's health and for the establishment of all regulations (pertaining to it) with the aim of improving the health standards of the nation and of abolishing all conditions prejudicial to health" according to the Council of People's Commissars in 1921.[19] It established new organisations, sometimes replacing old ones: the All Russia Federated Union of Medical Workers, the Military Sanitary Board, the State Institute for Social Hygiene, the Petrograd Skoraya Emergency Care, and the Psychiatry Commission.

In 1920 the world's first state rest-home for workers was set up, followed in 1925 by the world's first health resort, in Yalta, for agricultural workers.[20]

Most pharmacies and pharmaceutical factories were nationalised in 1917 but it was not a uniform process. In 1923 25% of pharmacies were still privately owned. There was heavy reliance on imported medicine and ingredients. 70% of all pharmaceuticals and 88% of drugs were produced locally by 1928. Local pharmacy schools were established in many cities.[21]

In 1923 there were 5440 physicians in Moscow. 4190 were salaried state physicians. 956 were registered as unemployed. Low salaries were often supplemented by private practice. In 1930 17.5% of Moscow doctors were in private practice. The number of medical students increased from 19,785 in 1913 to 63,162 in 1928 and to 76,027 by 1932.[22] When Mikhail Vladimirsky took over the Commissariat of Public Health in 1930 90% of the doctors in Russia worked for the State.

There were 12 bacteriological institutes in 1914. 25 more opened in the years up to 1937, some in the outlying regions such as the Regional Institute for Microbiology and Epidemiology in South East Russia which was based in Saratov. The emergency service, Skoraya Medical Care, revived after 1917. By 1927 there were 50 stations offering basic medical aid to victims of road accidents and of accidents in public places and responding to medical emergencies. The Scientific Practical Skoraya Care Institute opened in 1932 in Leningrad, running training courses for doctors. 15% of the emergency work was with children under 14.[23]

Spending on medical services increased from 140.2 million rubles per year to 384.9 million rubles between 1923 and 1927, but funding from that point barely kept up with population increases. By 1928 there were 158,514 hospital beds in urban areas, 59,230 in rural areas, 5,673 medical-centre beds in urban areas and 7,531 in rural areas, 18,241 maternity beds in urban areas and 9,097 in rural areas. 2000 new hospitals were built between 1928 and 1932. In 1929 Gosplan projected health spending to be 16% of the total government budget.[24]

Semashko system

As a self-defined socialist society, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR, founded in 1922) developed a totally state-run health-care model—the Semashko system — centralized, integrated, and hierarchically organised with the government providing state-funded health care to all citizens. All health personnel were state employees. Control of communicable diseases had priority over non-communicable ones. On the whole, the Soviet system tended to prioritize primary care, and placed much emphasis on specialist and hospital care. P. Mihály, writing in 2000, characterized the original Semashko model as a "coherent, cost-effective system to cope with the medical necessities of its own time".[25]

The integrated model achieved considerable success in dealing with infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, typhoid fever and typhus. The Soviet healthcare system provided Soviet citizens with competent, free medical care and contributed to the improvement of health in the USSR.[26] By the 1960s, life and health expectancies in the Soviet Union approximated to those in the US and in non-Soviet Europe.

In the 1970s, a transition was made from the Semashko model to a model that emphasizes specialization in outpatient care.

The effectiveness of the new model declined with under-investment, with the quality of care beginning to decline by the early 1980s, though in 1985 the Soviet Union had four times the number of doctors and hospital beds per head compared with the USA.[2] The quality of Soviet medical care became low by developed-world standards. Many medical treatments and diagnoses were unsophisticated and substandard (with doctors often making diagnoses by interviewing patients without conducting any medical tests), the standard of care provided by healthcare providers was poor, and there was a high risk of infection from surgery. The Soviet healthcare system was plagued by shortages of medical equipment, drugs, and diagnostic chemicals, and lacked many medications and medical technologies available in the Western world. Its facilities had low technical standards, and medical personnel underwent mediocre training. Soviet hospitals also offered poor hotel amenities such as food and linen. Special hospitals and clinics existed for the nomenklatura which offered a higher standard of care, but one still often below Western standards.[27][28][29]

Despite a doubling in the number of hospital beds and doctors per capita between 1950 and 1980, the lack of money that had been going into health was patently obvious. Some of the smaller hospitals had no radiology services, and a few had inadequate heating or water. A 1989 survey found that 20% of Russian hospitals did not have piped hot water and 3% did not even have piped cold water. 7% did not have a telephone. 17% lacked adequate sanitation facilities. Every seventh hospital and polyclinic needed basic reconstruction. By 1997, five years after the reforms described below, WHO estimated health expenditure per capita in the Russian Federation in 1997 as 251 US dollars, as opposed to $1,211 in Spain, $1,193 in the UK, $1,539 in Finland and $3,724 in the United States.[30]

Reform in 1991–1993

The new Russia has changed to a mixed model of health care with private financing and provision running alongside state financing and provision. Article 41 of the 1993 constitution confirmed a citizen's right to healthcare and medical assistance free of charge.[31] This is achieved through compulsory medical insurance (OMS) rather than just tax funding. This and the introduction of new free market providers was intended to promote both efficiency and patient choice. A purchaser-provider split was also expected to help facilitate the restructuring of care, as resources would migrate to where there was greatest demand, reduce the excess capacity in the hospital sector and stimulate the development of primary care. Finally, it was intended that insurance contributions would supplement budget revenues and thus help to maintain adequate levels of healthcare funding.

The OECD reported[32] that unfortunately, none of this has worked out as planned and the reforms have in many respects made the system worse. The population's health has deteriorated on virtually every measure. Though this is by no means all due to the changes in health care structures, the reforms have proven to be fully inadequate at meeting the needs of the nation. Private health care delivery has not managed to make many inroads and public provision of health care still predominates.

The resulting system is overly complex and very inefficient. It has little in common with the model envisaged by the reformers. Although there are more than 300 private insurers and numerous public ones in the market, real competition for patients is rare leaving most patients with little or no effective choice of insurer, and in many places, no choice of health care provider either. The insurance companies have failed to develop as active, informed purchasers of health care services. Most are passive intermediaries, making money by simply channelling funds from regional OMS funds to healthcare providers.

According to Mark Britnell the constitutional right to healthcare is "blocked by opaque and bureaucratic systems of planning and regulation", reimbursement rates which do not cover providers costs and high levels of informal payment to secure timely access. There is a "mosaic" of federal and state level agencies responsible for managing the public system.[2]

Recent developments

_-v3_-diff.png.webp)

Starting 2000, there was significant growth in spending for public healthcare[33] and in 2006 it exceed the pre-1991 level in real terms.[33] Also life expectancy increased from 1991–93 levels, infant mortality rate dropped from 18.1 in 1995 to 8.4 in 2008.[34]

In May 2012 Putin signed the May Decrees which included a plan to double the wages of healthcare staff by 2018 and gradual privatisation of state health services. In November 2014 the wage rises in Moscow led to the closure of 15 hospitals and 7,000 redundancies.[2]

In 2011, Moscow's government launched a major project known as UMIAS as part of its electronic healthcare initiative. UMIAS stands for Integrated Medical Information and Analytical System of Moscow.[35] The aim of the project is to make healthcare more convenient and accessible for Muscovites.

The private health insurance market, known in Russian as voluntary health insurance (Russian: добровольное медицинское страхование, ДМС) to distinguish it from state-sponsored Mandatory Medical Insurance, has experienced sustained levels of growth, owing to dissatisfaction with the level of services provided by state hospitals.[36] It was introduced in October 1992.[37] Perceived advantages of private healthcare include access to modern medical equipment and shorter waiting lists for specialist treatment.[36] Private health insurance is most common in the larger cities such as Moscow and St Petersburg, as income levels in most of Russia are still too low to generate a significant level of demand.[36]

Revenues for the leading private medical institutions in the country reached €1 billion by 2014, with double-digit levels of growth in the previous years.[38] As a result of the financial crisis in Russia, the proportion of companies offering health insurance fell from 36% to 32% in 2016.[39] The number of people covered by a voluntary healthcare policy in Moscow was 3.1 million in 2014, or 20.8% of the population.[40]

For the most part, policies are funded by employers, though insurance can also be purchased individually.[36] Another important market for insurers are immigrant workers, who are required to purchase health insurance to obtain work permits.[41] The average yearly cost of an employer-sponsored scheme ranged from 30,000 to 40,000 rubles ($530 - $700) in 2016, while prices for individuals were about 30% higher.[41] Critical conditions, such as cancer or heart disease, are often excluded from entry-level policies.[41]

The Russian health insurance market is oriented towards large companies, with corporate clients accounting for 90% of all the policies.[42] Small and medium-sized enterprises are far less likely to provide healthcare.[41] Some companies choose to offer health insurance only to selected categories of employees.[39]

Most of the individuals who buy health insurance are related to people covered by employer-sponsored schemes, with the rest accounting for less than 2% of all policies.[43] As companies cut back on their healthcare policies, employees in some cases resort to buying them individually.[43]

The largest private healthcare provider by revenue is Medsi,[38] whose main shareholder is the Sistema conglomerate.[43] Foreign healthcare providers with a presence in Russia include Fresenius, which has a network of dialysis centers in the country.[38] Fertility and maternity clinics are an important element of the Russian private healthcare network. The Mother and Child network of clinics accounts for 9% of all IVF treatment cycles in the country.[43]

Leading providers of healthcare insurance in Russia included Sogaz, Allianz, RESO-Garantia, AlfaStrakhovanie as well as the formerly state-owned Rosgosstrakh and Ingosstrakh.[44] RESO-Garantia is unusual among large insurance companies in that individual customers account for 40% of the policies.[43] Some insurance companies, such as Ingosstrakh, also own a network of clinics.[45]

Since 1996 government health facilities have been allowed to offer private services, and since 2011 some private providers have been providing services to the state-insured. The private sector in Moscow has expanded rapidly. One chain, Doktor Ryadom, treats half its patients under the official insurance scheme at low cost and the other half privately at a profit.[2]

Pro-natal policy

In an effort to stem Russia's demographic crisis, the government is implementing a number of programs designed to increase the birth rate and attract more immigrants to alleviate the problem. The government has doubled monthly child support payments and offered a one-time payment of 250,000 Rubles (around US$4,000) to women who had a second child since 2007.[46]

In 2006, the Minister of Health Mikhail Zurabov and Deputy Chairman of the State Duma Committee for Health Protection Nikolai Gerasimenko proposed reinstating the Soviet-era tax on childlessness, which ended in 1992.[47] So far, it has not been reinstated.[47]

In 2007, Russia saw the highest birth rate since the collapse of the USSR.[48] The First Deputy PM also said about 20 billion rubles (about US$1 billion) will be invested in new prenatal centres in Russia in 2008–2009. Immigration is increasingly seen as necessary to sustain the country's population.[49] By 2010, number of Russians dropped by 4.31% (4.87 million) from the year of 2000, during the period whole Russia's population died out just by 1.59% (from 145.17 to 142.86 million).[50]

Dentistry

Soviet dental technology and dental health were considered notoriously bad. In 1991, the average 35-year-old had 12 to 14 cavities, fillings or missing teeth. Toothpaste was often not available, and toothbrushes did not conform to standards of modern dentistry. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, dental skills, products and technology has improved dramatically.[51]

Occupational health

There is no standard definition of “occupational health” in Russian language. This notion can be translated and explained as hygiene of labour (Гигиена труда), labour protection (Охрана труда), working sanitation (Производственная санитария), health inspection at a work place (Медико-социальная экспертиза) , etc.

According to Labour Code of the Russian Federation (Section X, Chapter 33, Article 209), the occupational health (or labour protection) – is a system of the preservation of employees' life and health in the process of labour activity which includes legal, socioeconomic, organizational, technical, sanitary, medical, treatment, preventive, rehabilitative and other measures.[52]

Mikhail Lomonosov was the first who started talking about occupational and labour health in pre-revolutionary Russia. In his book (1763) “First foundations of metallurgy or ore affairs” [53] Mikhail Lomonosov first touched the issue of organization of work and recovery process for people working in the mountains, how to improve their safety, and how to ventilate the mines. From the end of 1800s the hygiene at a work place was established as one of the subjects in Saint Petersburg Mining University.

The law about 8-hours working day (Восьмичасовой рабочий день) was one of the laws enacted first after the fall of the Russian Empire.

In 1918 the Soviet Labour Code was written. In 1922 the Code was supplemented by regulations for: work in dangerous and hazardous conditions, labour of women and children, working night shifts, etc.[54]

The Soviet period is characterized as the period of development of hygiene in the country. The government was controlling the hygiene at all the organizations in USSR. The scientific research institute of hygiene and occupational health [55] was established in Moscow in 1923, where the Soviet occupational health specialists got their qualifications and knowledge.[56]

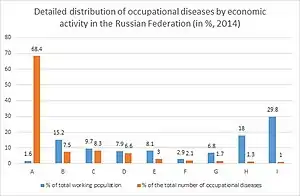

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the level of occupational morbidity in Russia has been lower than in most industrial countries. These levels are explained by a complex set of socioeconomic and psychosocial problems: an insufficient number of specialists in occupational medicine and the low level of their education; inadequate medical regulations for conducting mandatory medical examinations and for diagnosis and registration of occupational diseases; the economic dependence of the medical organizations from the employer during the procedure of mandatory medical examinations; and fear of a worker losing his or her job.[57] Due to the aforementioned reasons, the officially registered occupational morbidity rate in the Russian Federation for many decades (1990–2010) ranged from 1.0 to 2.5 cases per 10,000 employees. For modern Russia it is typical to have huge differences in occupational morbidity rates among various industries, ranging from 0.02 per 10,000 workers in wholesale and retail to 30 per 10,000 workers in mining. More than 90% of all newly diagnosed occupational diseases are found in 4 industries:

| Industry | % of occupational diseases |

|---|---|

| Mining | 68.4 |

| Agriculture, hunting, and forestry | 8.3 |

| Manufacturing | 7.5 |

| Transport and communications | 6.6 |

All the other procents are shared between construction, production, and dispensation of electricity, gas and water, health care, fisheries and fish farming. Detailed numbers are introduced in the Graph 2.

Occupational morbidity rates in the Russian Federation over the past few decades have declined, despite the continued increase in the proportion of jobs with poor working conditions. It can be assumed that with the current system of diagnosis and registration of occupational diseases, the level of occupational morbidity will continue to decline.[4]

See also

References

- Popovich, L; Potapchik, E; Shishkin, S; Richardson, E; Vacroux, A; Mathivet, B (2011). "Russian Federation. Health system review". Health Systems in Transition. 13 (7): 1–190, xiii–xiv. PMID 22455875.

- Britnell, Mark (2015). In Search of the Perfect Health System. London: Palgrave. pp. 81–84. ISBN 978-1-137-49661-4. Archived from the original on 2017-04-24.

- "Russian Statistical Yearbook 2018" (PDF). geohistory.today.

- Mazitova, Nailya N.; Simonova, Nadejda I.; Onyebeke, Lynn C.; Moskvichev, Andrey V.; Adeninskaya, Elena E.; Kretov, Andrey S.; Trofimova, Marina V.; Sabitova, Minzilya M.; Bushmanov, Andrey Yu (1 July 2015). "Current Status and Prospects of Occupational Medicine in the Russian Federation". Annals of Global Health. 81 (4): 576–586. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2015.10.002. PMID 26709290.

- "In Putin's Russia, Universal Health Care Is for All Who Pay". Bloomberg.com. 13 May 2015. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "Putin's Cutbacks in Health Care Send Russian Mortality Rates Back Up". Jamestown. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016.

- Introduced in the 1810s. Kan, Sergei: Memory Eternal, p. 95

- Khwaja, Barbara (26 May 2017). "Health Reform in Revolutionary Russia". Socialist Health Association. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- Leichter, Howard M (1980). A comparative approach to policy analysis: health care policy in four nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 202. OCLC 609576408.

- Leichter, Howard M (1980). A comparative approach to policy analysis: health care policy in four nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 204. OCLC 609576408.

- "Venereal Diseases | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". Archived from the original on 2017-06-13. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- Conroy, Mary Schaeffer (2006). The Soviet pharmaceutical business during the first two decades (1917–1937). New York: Peter Lang. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8204-7899-9. OCLC 977750545.

- Schaeffer Conroy, Mary: The Soviet Pharmaceutical Business During the First Two Decades (1917–1937), p. 32

- Fumurescu, Ana (2022). "Nurturing a "Great Social Organism": School Hygiene, Body Politics, and the State in Late Imperial Russia". History of Education Quarterly. 2 (1): 61–83. doi:10.1017/heq.2021.58. S2CID 246488902.

- Compare:

Keshavjee, Salmaan (2014). Blind Spot: How Neoliberalism Infiltrated Global Health. California Series in Public Anthropology. Vol. 30. Oakland, California: University of California Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-520-95873-9. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

One of the first decrees signed by the Bolsheviks [...] called for 'comprehensive sanitary legislation governing clean water, sewerage, industrial enterprises and residential housing.'

- Sigerist, Henry Ernest; Older, Julia (1947). Medicine and health in the Soviet Union. New York: The Citadel Press. p. 77. OCLC 610758721.

- Dewar, Margaret (1956). Labour policy in the USSR, 1917–1928. London: Royal Institute of International Affairs. p. 166. OCLC 877346228.

- Starks, Tricia A. (November 2017). "Propagandizing the Healthy, Bolshevik Life in the Early USSR". American Journal of Public Health. 107 (11): 1718–1724. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304049. PMC 5637674. PMID 28933923.

- Sigerist, Henry Ernest; Older, Julia (1947). Medicine and Health in the Soviet Union. Citadel Press. p. 25. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Lazebnyk, Stanislav; Orlenko, Pavlo (1989). Ukraine questions and answers. Kiev: Politvidav Ukraini Publishers. p. 139. ISBN 9785319003867. OCLC 21949577.

- Compare:

Schaeffer Conroy, Mary (2006). The Soviet pharmaceutical business during its first two decades (1917–1937). American university studies: Series IX, History, ISSN 0740-0462. Vol. 202. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-7899-9. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

Higher pharmacy schools did emerge in Moscow, Leningrad, Khar'kov, Odessa, and some other cities.

- Sigerist, Henry Ernest; Older, Julia (1947). Medicine and health in the Soviet Union. New York: The Citadel Press. p. 53. OCLC 610758721.

- Messel', Meer Abramovich; John E. Fogarty International Center for Advanced Study in the Health Sciences; Geographic Health Studies (1975). Urban emergency medical service of the city of Leningrad. Bethesda, Md.: U.S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health. pp. 5–7. OCLC 609575886.

- Khwaja, Barbara (26 May 2017). "Health Reform in Revolutionary Russia". Socialist Health Association. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

In 1929 the government economic planning agency, Gosplan USSR, projected health spending to be 16% of total government budget, a 5.6% increase in the number of hospital beds and a 6.9% increase in the number of doctors but once again there was only a slight increase in per capita spending,around 2%.

- Quoted in:

OECD (2001). The Social Crisis in the Russian Federation. Paris: OECD Publishing. p. 95. ISBN 9789264192454. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

[...] 'the original Semashko model was a coherent, cost-effective system to cope with the medical necessities of its own time' [...].

- Leichter, Howard M.: A Comparative Approach to Policy Analysis: Health Care Policy in Four Nations, p. 226

- Davis, Christopher, ed. (1989). Models of disequilibrium and shortage in centrally planned economies. Charemza, W. London: Chapman and Hall. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-412-28420-5. OCLC 260151881.

- Dyczok, Marta (2013). Ukraine: Movement without Change, Change without Movement. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-134-43262-2. OCLC 862613488.

- Eaton, Katherine Bliss (2004). Daily life in the Soviet Union. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-313-31628-9. OCLC 863808526.

- WHO: World Health Report 2000, pp 192-195

- "The Constitution of the Russian Federation".

- "HEALTHCARE REFORM IN RUSSIA: PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT WORKING PAPERS No. 538". The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- "Public Spending in Russia for Healthcare" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03.

- "Russian State Institute of Demography". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14.

- "EMIAS, Moscow". Infomatika. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "ДМС в России - добровольное медицинское страхование - MetLife". MetLife (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "За медуслуги платят более половины российских горожан". Vedomosti. 24 October 2011. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "Рейтинг РБК: 25 крупнейших частных медицинских компаний России". РБК. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "Все меньше компаний приобретают полисы ДМС для сотрудников – НАФИ". 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "РБК Исследования рынков . В 2014 г. численность пациентов ДМС в Москве составила 3,1 млн человек". marketing.rbc.ru. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "Анализ рынка ДМС в России в 2011–2015 гг, прогноз на 2016–2020 гг, BusinesStat, 2016 - РБК маркетинговые исследования". marketing.rbc.ru. Archived from the original on 2017-04-24. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "Куда идти прикрепиться". Газета РБК. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "Спрос на платные медицинские услуги растет". 9 November 2015. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "В Петербурге составили рейтинг страховщиков, работающих в системе ДМС". Страхование сегодня. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ""Ингосстраху" требуются пациенты". Коммерсантъ (Омск). 20 January 2011. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "Country Profile: Russia" (PDF). Library of Congress—Federal Research Division. October 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-01-02. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- "Childless Russian families to pay taxes for their social inaction," "Childless Russian families to pay taxes for their social inaction". 15 September 2006. Archived from the original on 2013-06-03. Retrieved 2013-01-21. (accessed January 3, 2010.)

- "Russian policies ignite unprecedented birth rate in 2007". The Economic Times. February 2, 2008. Archived from the original on January 10, 2009. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- "United Nations Expert Group Meeting On International Migration and Development" (PDF). Population Division; Department of Economic and Social Affairs; United Nations Secretariat. 6–8 July 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- "Росстат опубликовал окончательные итоги переписи населения". РБК. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- Niedowski (2007). "Dentistry in Russia is finally leaving the Dark Ages behind". Chicago Tribune.

- https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/acc_e/rus_e/wtACCrus58_LEg_363.pdf

- Mikhail Lomonosov First foundations of metallurgy or ore affairs.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Heller, P. R. (1951). "Soviet Labour Law". Soviet Studies. 2 (4): 378–86. doi:10.1080/09668135108409794. JSTOR 149075.

- "Occupational hygiene and health care history". irioh.ru.

- "History of the labour hygiene". ogigienetruda.ru (in Russian).

- The journal about healthy working [In Russian] http://www.8hours.ru/journal/2015/04/files/assets/basic-html/page64.html