Energy in Russia

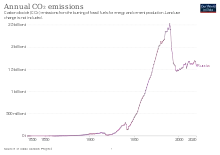

Energy consumption across Russia in 2020 was 7,863 TWh.[1] Russia is a leading global exporter of oil and natural gas[2] and is the fourth highest greenhouse emitter in the world. As of September 2019, Russia adopted the Paris Agreement [3] In 2020, CO2 emissions per capita were 11.2 tCO2.[4]

.jpg.webp)

Overview

Russia has been widely described as an energy superpower.[5] It has the world's largest proven gas reserves,[6] the second-largest coal reserves,[7] the eighth-largest oil reserves,[8] and the largest oil shale reserves in Europe.[9] Russia is also the world's leading natural gas exporter,[10] the second-largest natural gas producer,[11] and the second-largest oil producer and exporter.[12][13] Russia's oil and gas production has led to deep economic relationships with the European Union, China, and former Soviet and Eastern Bloc states.[14][15] For example, over the last decade, Russia's share of supplies to total European Union (including the United Kingdom) gas demand increased from 25% in 2009 to 32% in the weeks before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.[15] Russia relies heavily on revenues from oil- and gas-related taxes and export tariffs, which accounted for 45% of its federal budget in January 2022.[16]

Russia is the world's fourth-largest electricity producer,[17] and the ninth-largest renewable energy producer in 2019.[18] It was also the world's first country to develop civilian nuclear power, and constructed the world's first nuclear power plant.[19] Russia was also the world's fourth-largest nuclear energy producer in 2019,[20] and was the fifth-largest hydroelectric producer in 2021.[21]

Energy sources

Russia is rich in energy resources. Russia has the largest known natural gas reserves of any state on earth, along with the second largest coal reserves, and the eighth largest oil reserves. This is 32% of world proven natural gas reserves (23% of the probable reserves), 12% of the proven oil reserves, 10% of the explored coal reserves (14% of the estimated reserves) and 8% of the proven uranium reserves.[22]

With recent acquisitions, Russia has gained assets in the Black Sea that may be worth trillions of dollars.[23]

Natural gas

Russia is the world's second largest producer of natural gas, and has the world's largest gas reserves. Russia used to be the world's largest gas exporter. Gazprom and Novatek are Russia's main gas producers, but many Russian oil companies, including Rosneft, also operate gas production facilities. Gazprom, which is state-owned, is the largest gas producer, but its share of production has declined over the past decade, as Novatek and Rosneft have expanded their production capacity. However, Gazprom still accounted for 68% of Russian gas production in 2021. Historically, production was concentrated in West Siberia, but investment has shifted in the past decade to Yamal and Eastern Siberia and the Far East, as well as the offshore Arctic.[2][15][14]

Russia also has a wide-reaching gas export pipeline network, both via transit routes through Belarus and Ukraine, and via pipelines sending gas directly into Europe (including the Blue Stream, and TurkStream pipelines). Russia natural gas in 2021 accounted for 45% of imports and almost 40% of European Union gas demand.[2]

In late 2019, Russia launched a major eastward gas export pipeline, the roughly 3,000 km-long Power of Siberia pipeline, in order to be able to send gas from far east fields directly to China. Russia is looking to develop the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, with a capacity of 50 bcm/year, which would supply China from the West Siberian gas fields. No supply agreements and no final investment decision have yet been reached on the pipeline.[2]

Furthermore, Russia has been expanding its liquefied natural gas (LNG) capacity, in order to compete with growing LNG exports from the United States, Australia and Qatar. In 2021, Russia exported 40 bcm of LNG, making it the world's 4th largest LNG exporter and accounting for approximately 8% of global LNG supply.[2]

In recent years, Russia has increasingly focused on the Arctic as a way to increase oil and gas production. The Arctic accounts for over 80% of Russia's natural gas production and an estimated 20% of its crude production. While climate change threatens future investment in the region, it also presents Russia with the opportunity of increasing access to Arctic trade routes, allowing for further flexibility for seaborne deliveries of fossil fuels, particularly to Asia.[2]

In 2022 Russia lost 75% of their export market following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[24]

Oil

Russia is a major player in global energy markets. It is one of the world's top three crude oil producers, vying for the top spot with Saudi Arabia and the United States. In 2021, Russian crude and condensate output reached 10.5 million barrels per day (barrels per day), making up 14% of the world's total supply. Russia has oil and gas production facilities throughout the country, but the bulk of its fields are concentrated in western and eastern Siberia. China is the largest importer of Russian crude (making up 20% of Russian exports),[2][14][15] but Russia exports a significant volume to buyers in Europe.[2]

While the Russian oil industry has seen a period of consolidation in recent years, several major players remain. Rosneft, which is state-owned, is the largest oil producer in Russia. It is followed by Lukoil, which is the largest privately owned oil company in the country. Gazprom Neft, Surgutneftegaz, Tatneft and Russneft also have significant production and refining assets.[2]

Russia has extensive crude export pipeline capacity, allowing it to ship large volumes of crude oil directly to Europe as well as Asia. The roughly 5,500 km Druzhba pipeline system, the world's longest pipeline network, transports 750,000 bpd of crude directly to refiners in east and central Europe. At present, Russia supplies roughly 20% of total European refinery crude throughputs. In 2012, Russia launched the 4,740 km 1.6 million bpd Eastern Siberia—Pacific Ocean oil pipeline, which sends crude directly to Asian markets such as China and Japan. The pipeline was part of Russia's general energy pivot to Asia, a strategy focused on shifting export dependence away from Europe, and taking advantage of growing Asian demand for crude. Russia also ships crude by tanker from the Northwest ports of Ust-Luga and Primorsk, as well as the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk, and Kozmino in the Far East. In addition, Russia also exports crude by rail.[2]

Russia has an estimated 6.9 million bpd of refining capacity, and produces a substantial amount of oil products, such as gasoline and diesel. Russian companies have spent the last decade investing heavily in refining capacity in order to take advantage of favorable government taxation, as well as growing global diesel demand. As a result, Russia has been able to shift the vast majority of its motor fuel production to meet EU standards.[2]

Russia's energy strategy has prioritized self-sufficiency in gasoline, so it tends to export minimal volumes. However, Russian refiners produce roughly double the diesel needed to satisfy domestic demand, and typically export half their annual production, much of it to European markets. Europe remains a major market for Russian oil products. In 2021 Russia exported 750,000 bpd of diesel to Europe, meeting 10% of demand.[2]

Coal

Russia has the world's second largest coal reserves, with 157 billion tonnes of reserves.

Russian coal reserves are widely dispersed. The principal hard coal deposits are located in the Pechora and Kuznetsk basins. The Kansk-Achinsk basin contains huge deposits of brown coal. The Siberian Lena and Tunguska basins are largely unexplored resources, which would probably be difficult to exploit commercially.[25]

Hydropower

Hydropower accounts for about 20% of Russia's total electric power production. The country has 102 hydropower plants in operation, with RusHydro the world's second-largest hydroelectric power producer.[26]

Hydro generation (including pumped-storage output) in 2020 was 196 TWh, which represents 4.4% of world hydroelectricity generation. In 2020 installed hydroelectric generating capacity was 49.9 GW, making Russia the seventh largest hydroelectricity producer in the world.[27]

Gross theoretical potential of the Russian hydro resource base is 2,295 TWh per year, of which 852 TWh is regarded as economically feasible. Most of this potential is located in Siberia and the Far East.[28]

Nuclear power

Nuclear power produced 216 TWh of electricity in 2020, representing 20% of Russian electricity production and 11.8% of global nuclear power production.[29] There are thirty-eight nuclear reactors in operation across Russia producing 29.4 GW of electricity. Four new reactors are under construction, with a further thirty-four in various stages of planning.

From 2001, all Russian civil reactors were operated by Energoatom. On 19 January 2007, Russian Parliament adopted legislation which created Atomenergoprom - a holding company for all Russian civil nuclear industry, including Energoatom, the nuclear fuel producer and supplier TVEL, the uranium trader Tekhsnabexport (Tenex) and nuclear facilities constructor Atomstroyexport.

Uranium exploration and development activities have been largely concentrated on three east-of-Urals uranium districts (Transural, West Siberia and Vitim). The most important uranium-producing area has been the Streltsovsky region near Krasnokamensk in the Chita Oblast. In 2019, Russia was the world's seventh largest producer of uranium, accounting for 4.7% of global output.[30]

Peat

Principal peat deposits are located in the north-western parts of Russia, in West Siberia, near the western coast of Kamchatka and in several other far-eastern regions. The Siberian peatlands account for nearly 75% of Russia's total reserves of 186 billion tonnes, second only to Canada's. Approximately 5% of exploitable peat (1.5 million tonnes per annum) is used for fuel production. Although peat was used as industrial fuel for power generation in Russia for a long period, its share has been in long-term decline, and since 1980 has amounted to less than 1%.[31]

Renewable energy

Low prices for energy and in particular subsidies for natural gas hinder renewable energy development in Russia.[32] Russia lags behind other countries in creating a conducive framework for renewable energy development.[33] Non-hydroelectric renewable energy in Russia is largely undeveloped although Russia has many potential renewable energy resources.

Geothermal energy

Geothermal energy, which is used for heating and electricity production in some regions of the Northern Caucasus and the Far East, is the most developed renewable energy source in Russia after hydroelectric energy.[34] Geothermal resources have been identified in the Northern Caucasus, Western Siberia, Lake Baikal, and in Kamchatka and the Kuril Islands. In 1966 a 4 MWe single-flash plant was commissioned at Pauzhetka (currently 11 MWe) followed by a 12 MWe geothermal power plant at Verkhne Mutnovsky, and 50 MWe Mutnovsky geothermal power plant. At the end of 2005 installed capacity for direct use amounted to more than 307 MWt.[35]

Solar energy

It has been estimated that Russia's gross potential for solar energy is 2.3 trillion tce. The regions with the best solar radiation potential are the North Caucasus, the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea areas, and southern parts of Siberia and the Far East. This potential is largely unused, although the possibilities for off-grid solar energy or hybrid applications in remote areas are huge. However, the construction of a single solar power plant Kislovodskaya SPP (1.5 MW) has been delayed.[36]

Wind energy

Russia has high quality wind resources on the Pacific and Arctic coasts and in vast steppe and mountain areas. Large-scale wind energy systems are suitable in Siberia and the Far East (east of Sakhalin Island, the south of Kamchatka, the Chukotka Peninsula, Vladivostok), the steppes along the Volga river, the northern Caucasus steppes and mountains and on the Kola Peninsula, where power infrastructure and major industrial consumers are in place. At the end of 2006, total installed wind capacity was 15 MW. Major wind power stations operate at Kalmytskaya (2 MW), Zapolyarnaya (1.5 MW), Kulikovskaya (5.1 MW), Tyupkildi (2.2 MW) and Observation Cape (2.5 MW). Feasibility studies are being carried out on the Kaliningradskaya (50 MW) and the Leningradskaya (75 MW) wind farms. There are about 100 MW of wind projects in Kalmykia and in Krasnodar Krai.[37]

Tidal energy

A small pilot tidal power plant with a capacity of 400 kW was constructed at Kislaya Guba near Murmansk in 1968. In 2007, Gidro OGK, a subsidiary of the Unified Energy System (UES) began the installation of a 1.5 MW experimental orthogonal turbine at Kislaya Guba. If it proves successful, UES plans to continue with Mezen Bay (15,000 MW) and Tugur Bay (7,980 MW) projects.[38]

Electricity sector

Russia is the world's fourth largest electricity producer after China, the United States, and India. In 2020, Russia produced 1,085 TWh[39] and exported 20 TWh of electricity.[40]

Roughly 60% of Russia's electricity is generated by fossil fuels, 20% by hydroelectricity, 20% by nuclear reactors.[39] Renewable energy generation is minimal.

Russia exports electricity to the CIS countries, Latvia, Lithuania, China, Poland, Turkey and Finland.

Billionaires

Russian billionaires in energy by Forbes in 2013 included No 41 Mikhail Fridman ($16.5 B), No 47 Leonid Michelson ($15.4 B), 52 Viktor Vekselberg ($15.1 B), 55 Vagit Alekperov ($14.8 B), 56 Andrey Melnichenko ($14.4 B), 62 Gennady Timchenko ($14.1 B), 103 German Khan ($10.5 B), 138 Alexei Kuzmichov ($8.2 B), 162 Leonid Fedun ($7.1 B), 225 Pyotr Aven ($5.4 B), 423 Vladimir Bogdanov ($3.2 B), 458 Mikhail Gutseriev ($3 B), 641 Alexander Dzhaparidze ($2.3 B), 792 Igor Makarov ($1.9 B), 882 Anatoly Skurov ($1.7 B), 974 Vladimir Gridin and family ($1.5 B), 974 Andrei Kosogov ($1.5 B), 1031Farkhad Akhmedov ($1.4 B), 1088 Alexander Putilov ($1.35 B), 1161 Mikhail Abyzov ($1.25 B) and 1175 Konstantin Grigorishin ($1.2 B).[41]

See also

- Economy of Russia

- Energy policy of Russia

- Petroleum industry in Russia

- Oil reserves in Russia

- Russia in the European energy sector

- Mining industry of Russia

- List of oil and gas fields of the Barents Sea

- Oil megaprojects (2011)

- Petroleum exploration in the Arctic

- European countries by fossil fuel use (% of total energy)

- European countries by electricity consumption per person

- Climate change in Russia

- Greenhouse gas emissions by Russia

- List of power stations in Russia

- Energy policy of the Soviet Union

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Frequently Asked Questions on Energy Security, International Energy Agency.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Frequently Asked Questions on Energy Security, International Energy Agency.

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Energy Fact Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?, International Energy Agency.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Energy Fact Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?, International Energy Agency.

References

- "BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2021" (PDF). Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- International Energy Agency (21 March 2022). "Energy Fact Sheet: Why does Russian oil and gas matter?". IEA. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- Sauer, Natalie (24 September 2019). "Russia formally joins Paris climate pact". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- "Russia Energy Information | Enerdata". www.enerdata.net. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- Gustafson, Thane (20 November 2017). "The Future of Russia as an Energy Superpower". Harvard University Press. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- "Natural gas – proved reserves". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- "Statistical Review of World Energy 69th edition" (PDF). bp.com. BP. 2020. p. 45. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- "Crude oil – proved reserves". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- 2010 Survey of Energy Resources (PDF). 2010. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-946121-02-1. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - "Natural gas – exports". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- "Natural gas – production". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- "Crude oil – production". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- "Crude oil – exports". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- International Energy Agency (24 February 2022). "Oil Market and Russian Supply". IEA. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- International Energy Agency (24 February 2022). "Gas Market and Russian Supply". IEA. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- International Energy Agency (13 April 2022). "Frequently Asked Questions on Energy Security". IEA. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- "Electricity – production". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Whiteman, Adrian; Rueda, Sonia; Akande, Dennis; Elhassan, Nazik; Escamilla, Gerardo; Arkhipova, Iana (March 2020). Renewable capacity statistics 2020 (PDF). p. 3. ISBN 978-92-9260-239-0. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Long, Tony (27 June 2012). "June 27, 1954: World's First Nuclear Power Plant Opens". Wired. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- "Nuclear Power Today". world-nuclear.org. World Nuclear Association. October 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Whiteman, Adrian; Akande, Dennis; Elhassan, Nazik; Escamilla, Gerardo; Lebedys, Arvydas; Arkhipova, Lana (2021). Renewable Energy Capacity Statistics 2021 (PDF). Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency. ISBN 978-92-9260-342-7. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- "Country Analysis Briefs: Russia". Energy Information Administration. April 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- In Taking Crimea, Putin Gains a Sea of Fuel Reserves

- "Russia approves big hikes in Gazprom's domestic gas prices". 18 July 2023.

- WEC (2007), p.34-35

- RusHydro

- "Status Report". www.hydropower.org. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- WEC (2007), p. 308

- "Росатом Госкорпорация "Росатом" ядерные технологии атомная энергетика АЭС ядерная медицина". www.rosatom.ru. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- "World Uranium Mining - World Nuclear Association". world-nuclear.org. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- WEC (2007), p. 331

- Øverland, Indra; Kjærnet, Heidi (2009). Russian renewable energy: The potential for international cooperation. Ashgate.

- Overland, Indra (2010). "The Siberian Curse: A Blessing in Disguise for Renewable Energy?". Sibirica Journal of Siberian Studies. 9: 1–20.

- Russia: Energy overview, by BBC News 13 February 2006

- WEC (2007), pp. 470-471

- WEC (2007), p.420

- WEC (2007), pp. 515-516

- WEC (2007), pp.538-539

- "Russia's energy market in 2020" (PDF). Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- "Russia Electricity exports - data, chart". TheGlobalEconomy.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- Billionaires Energy Russia 2013