Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge

The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge was a minor conflict of the American Revolutionary War fought near Wilmington (present-day Pender County), North Carolina, on February 27, 1776. The victory of the North Carolina Provincial Congress' militia force over British governor Josiah Martin's and Tristan Worsley's reinforcements at Moore's Creek marked the decisive turning point of the Revolution in North Carolina. American independence would be declared less than five months later.

| Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Reconstructed earthworks at Moores Creek Battlefield | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,050 militia[1] |

Start of march: 1,400–1,600[2][3] Battle: 900–1000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 killed 1 wounded[1] |

50 killed or wounded 850 captured[1] | ||||||

Moore's Creek Bridge Location within North Carolina  Moore's Creek Bridge Moore's Creek Bridge (the United States) | |||||||

Loyalist recruitment efforts in the interior of North Carolina began in earnest with news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and patriots in the province also began organizing Continental Army and militia. When word arrived in January 1776 of a planned British Army expedition to the area, Martin ordered his militia to muster in anticipation of their arrival. Revolutionary militia and Continental units mobilized to prevent the junction, blockading several routes until the poorly armed loyalists were forced to confront them at Moore's Creek Bridge, about 18 miles (29 km) north of Wilmington.

In a brief early-morning engagement, a Highland charge across the bridge by sword-wielding loyalists shouting in Scottish Gaelic was met by a barrage of musket and artillery fire. Two loyalist leaders were killed, another captured, and the whole force was scattered. In the following days, many loyalists were arrested, putting a damper on further recruiting efforts. North Carolina was not militarily threatened again until 1780, and memories of the battle and its aftermath negated efforts by Charles Cornwallis to recruit loyalists in the area in 1781.

Background

British recruiting

In early 1775, with political and military tensions rising in the Thirteen Colonies, North Carolina's royal governor, Josiah Martin, hoped to combine the recruiting of Scots Gaels in the North Carolina interior with that of sympathetic former Regulators (a group originally opposed to corrupt colonial administration) and disaffected loyalists in the coastal areas to build a large loyalist force to counteract patriot sympathies in the province.[4] His petition to London to recruit an army of 1,000 men had been rejected, but he continued efforts to rally loyalist support.[5]

At about the same time, Allan Maclean of Torloisk, despite having fought for Prince Charles Edward Stuart during the Jacobite rising of 1745, petitioned King George III for permission to recruit Scottish Loyalists throughout North America. In April, he received royal assent to recruit a regiment to be known as the Royal Highland Emigrants from demobilized veterans of the Highland regiments now living as settlers in British North America.[6] One battalion was to be recruited in the northern provinces, including New York, Quebec and Nova Scotia, while a second battalion was to be raised in North Carolina and other southern Colonies, where a large number of Highland soldiers had been given land grants. After receiving his commissions from General Thomas Gage in June, Maclean of Torloisk dispatched Majors Donald MacLeod and Donald MacDonald, two officers in the 2nd battalion, 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) who had recently served under the command of Major John Small during the June 17 Battle of Bunker Hill, to lead the recruitment drive in the Carolinas. Both recruiting officers were already aware of the clandestine activities of Allan MacDonald, the former Tacksman of Kingsburgh, Skye for Clan MacDonald of Sleat, and the husband of the Jacobite heroine Flora MacDonald. Allan MacDonald, who had emigrated to the Colony just a few years previously, was actively recruiting a Loyalist militia in North Carolina.[7] The arrival of Majors MacLeod and MacDonald in the Colony's capital of New Bern raised the suspicions of local officials from North Carolina's Committee of Safety, but MacLeod and MacDonald, "represented they were only visiting their friends and relatives." In reality, according to John Patterson MacLean, "They were all British officers, on active service."[8] Although the New Bern Committee dispatched a report to their superiors at Wilmington,[9] both recruiting officers were allowed to proceed without being arrested.[10]

According to historian John Patterson MacLean, Major Donald MacDonald was in his 65th year and had extensive combat experience as an officer in the British Army. Like MacLean of Torloisk, however, MacDonald had previously fought for Prince Charles Edward Stuart during the Jacobite rising of 1745, during which the Major had, "headed many of his own name. He now found many of these former companions who readily listened to his persuasions."[11]

On January 3, 1776, Governor Josiah Martin learned that more than 2,000 redcoats under the command of General Henry Clinton had been dispatched for the southern colonies from Cork, Ireland. Their arrival was expected in mid-February.[12] Governor Martin immediately dispatched orders to all recruiting officers, decreeing that they were to be ready to lead their recruits to the coast by February 15th. Governor Martin also promoted Major Donald MacDonald to supreme commander of all British and Loyalist soldiers in the Colony of North Carolina, with the new rank of Brigadier General.[13]

Governor Martin also dispatched Alexander Maclean to Cross Creek with orders to coordinate activities in that area. Optimistically, Maclean promised Governor Martin to raise and equip 5,000 Regulators and 1,000 Gaels. Governor Martin, expecting an easy Loyalist victory, is reported to have said, "This is the moment when this country may be delivered from anarchy."[4][14]

Proclamations were sent out demanding that, "all the King's loyal subjects... repair to the King's Royal Standard, at Cross Creek... in order to join the King's Army; otherwise, they must expect to fall under the melancholy consequences of a declared rebellion, and expose themselves to the just resentment of an injured, though gracious Sovereign."[15] The latter statement would have been understood by North Carolina Highlanders as a threat that those who refused military service would be treated to both the land confiscations and the "arbitrary and malicious violence" used in the aftermath of the Battle of Culloden, which is still referred to in the Highlands and Islands as Bliadhna nan Creach ("The Year of the Pillaging").[16]

Beginning what would later be dubbed "The Insurrection of Clan Donald",[17] on February 1, 1776, Brigadier General MacDonald raised the Royal Standard in the Public Square of Cross Creek. Nightly balls were held and all other means were used to instill the military spirit.[18] Behind the scenes, however, the Loyalist leadership was divided.

In a meeting of Scottish and Regulator leaders at Cross Creek on February 5, the Scots wanted to wait until the British troops arrived before mustering, while the Regulators wanted to move immediately. The views of the latter prevailed, particularly since they claimed to be able to raise 5,000 men, while the Gaels expected to raise only 700-800.[4] When Loyalist forces gathered in Cross Creek on February 15, 1776, they numbered about 3,500 men.

According to J.P. MacLean, "When the day came, the Highlanders were seen coming from near and from far, from the wide plantations on the river bottoms, and from the rude cabins in the depths of the lonely pine forests, with broadswords at their side, in tartan garments and feather bonnet, and keeping step to the shrill music of the bag-pipe. There came, first of all, Clan MacDonald with Clan MacLeod near at hand, with lesser numbers of Clan MacKenzie, Clan Macrae, Clan MacLean, Clan MacKay, Clan MacLachlan, and still others - variously estimated at fifteen hundred to three thousand, including about two hundred others, principally Regulators. However, all who were capable of bearing arms did not respond to the summons, for some would not engage in a cause where their traditions and affections had no part. Many of them hid in the swamps and in the forests."[19]

According to tradition, as the Loyalist Gaels gathered around the Royal Standard in the Public Square of Cross Creek, the formerly Jacobite heroine Flora MacDonald, "made to them an address in their own Gaelic tongue that excited them to the highest pitch of warlike enthusiasm",[20] a tradition known among the Highland clans as a, "brosnachadh-catha"[21] or an, "incitement to battle."[22]

Despite Flora MacDonald's speech, however, the number of Loyalists dwindled rapidly over the next few days. Many of the Gaels had been promised that they would be met and escorted by British Army troops and did not favor having to fight all the way to the coast. When they marched from Cross Creek on February 18, 1776, Brigadier General Donald MacDonald led between 1,400 and 1,600 men, predominantly Scottish Gaels.[2][3] This number was further reduced over the coming days as more and more men deserted the column.[23]

Revolutionary reaction

Meanwhile, word of the Cross Creek muster reached the Patriots of the North Carolina Provincial Congress just a few days after it happened. The colonies were broadly prosperous on the eve of the American Revolution. Pursuant to resolutions of the Second Continental Congress, the provincial congress had raised the 1st North Carolina Regiment of the Continental Army in fall 1775, and given command to Colonel James Moore. Local committees of safety in Wilmington and New Bern also had active militia units, led by Alexander Lillington and Richard Caswell respectively. On February 15, the Provincial Congress' militia force began to mobilize.[3]

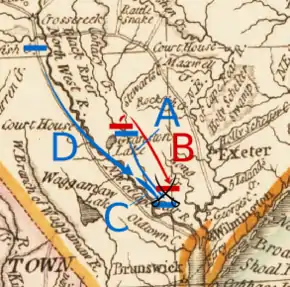

A: Moore moves from Wilmington to Rockfish Creek

B: MacDonald moves to Corbett's Ferry

C: Caswell moves from New Bern to Corbett's Ferry

Moore led 650 Patriot militiamen out of Wilmington with the objective of preventing the loyalists from reaching the coast. They camped on the southern shore of Rockfish Creek on February 15, about 7 miles (11 km) from the loyalist camp. General MacDonald learned of their arrival, and sent Colonel Moore a copy of a proclamation issued by Governor Martin and a letter calling on all Patriots to lay down their arms. Colonel Moore responded with his own call that the loyalists lay down their arms and support the cause of Congress.[3] In the meantime, Caswell led 800 New Bern District Brigade militiamen toward the area.[24] The Continentals included 58 English immigrants who had arrived in North Carolina during the 1730s and 1740s and who were fighting for the patriot cause, as well as 290 of their sons who had been born and raised in the New World. In addition to this were eleven Welshman and 39 of their American born sons who also fought under Lillington. Smaller numbers of Lowland Scots immigrants, primarily from Selkirkshire, Berwickshire and Roxburghshire were also present on the patriot side. Many of the men who fought under Lillington and Caswell were third generation Carolinians whose grandparents had been English immigrants who came as part of a large migration to the Carolinas from the English regions of Wiltshire, Northamptonshire, Hertfordshire as well as many farmers from the southern portion of Lincolnshire, England, during the early 1700s. By contrast, the Loyalist army facing them consisted exclusively of Gaelic-speaking Tories from the Scottish Highlands and Islands, some of whom owned large plantations along the Cape Fear River which was settled by recently arrived members of the Scottish nobility.[25]

Loyalist march

MacDonald, his preferred road blocked by Moore, chose an alternate route that would eventually bring his force to the Widow Moore's Creek Bridge, about 18 miles (29 km) from Wilmington. On February 20 he crossed the Cape Fear River at Cross Creek and destroyed the boats in order to deny Moore their use.[24] His forces then crossed the South River, heading for Corbett's Ferry, a crossing of the Black River. On orders from Moore, Caswell reached the ferry first, and set up a blockade there.[26] Moore, as a precaution against Caswell being defeated or circumvented, detached Lillington with 150 Wilmington militia and 100 men under Colonel John Ashe from the New Hanover Volunteer Company of Rangers to take up a position at the Widow Moore's Creek Bridge. These men, moving by forced marches, traveled down the southern bank of the Cape Fear River to Elizabethtown, where they crossed to the north bank. From there they marched down to the confluence of the Black River and Moore's Creek, and began entrenching on the east bank of the creek. Moore detached other militia companies to occupy Cross Creek, and followed Lillington and Ashe with the slower Continentals. They followed the same route, but did not arrive until after the battle.[24]

When MacDonald and his force reached Corbett's Ferry, they found the crossing blocked by Caswell and his men.[26] MacDonald prepared for battle, but was informed by a local slave that there was a second crossing a few miles up the Black River that they could use. On February 26, he ordered his rearguard to make a demonstration as if they were planning to cross while he led his main body up to this second crossing and headed for the bridge at Moore's Creek.[24] Caswell, once he realized that MacDonald had given him the slip, hurried his men the 10 miles (16 km) to Moore's Creek, and beat MacDonald there by only a few hours.[27] MacDonald sent one of his men into the patriot camp under a flag of truce to demand their surrender, and to examine the defences. Caswell refused, and the envoy returned with a detailed plan of the patriot fortifications.[28]

A: Caswell's movement

B: MacDonald's movement

C: Lillington and Ashe's movement

D: Moore's movement

Caswell had thrown up some entrenchments on the west side of the bridge, but these were not located to patriot advantage. Their position required the patriots to defend a position whose only line of retreat was across the narrow bridge, a distinct disadvantage that MacDonald recognized when he saw the plans.[27] In a council held that night, the loyalists decided to attack, since the alternative of finding another crossing might give Moore time to reach the area. During the night, Caswell decided to abandon that position and instead take up a position on the far side of the creek. To further complicate the loyalists' use of the bridge, the militia took up its planking and greased the support rails.[23]

Battle

By the time of their arrival at Moore's Creek, the loyalist contingent had shrunk to between 700 and 800 men. About 600 of these were Highland Scots and the remainder were Regulators.[29] Furthermore, the marching had taken its toll on the elderly Brigadier General MacDonald; he fell ill and turned over command to Lieutenant Colonel Donald MacLeod. The loyalists broke camp at 1 am on February 27 and marched the few miles from their camp to the bridge.[28]

During the night, Caswell and his men established a semicircular earthworks around the bridge end, and prepared to defend them with two small pieces of field artillery.

Arriving shortly before dawn, the Loyalists found the defenses on the west side of the bridge unoccupied. MacLeod ordered his men to adopt a defensive line behind nearby trees, but then a Patriot sentry across the river fired his musket to warn Caswell of the loyalist arrival. Hearing this, Lt.-Col. MacLeod immediately ordered his men to attack.[23]

In the pre-dawn mist, a company of Loyalist Gaels approached the bridge. In response to a Patriot call for identification shouted from across the creek, Captain Alexander Mclean identified himself as a friend of the King, and responded with his own challenge in Scottish Gaelic. Hearing no reply, he ordered his company to open fire, beginning an exchange of gunfire with the Patriot sentries. Lieutenant-Colonel MacLeod and Captain John Campbell then led a hand-picked company of swordsmen on a Highland charge across the bridge,[28] shouting in Gaelic, "King George and broadswords!"[30]

When the Loyalists were within 30 paces of the earthworks, the Patriot militia opened fire, to devastating effect. MacLeod and Campbell both went down in a hail of gunfire; Colonel Moore reported that MacLeod had been struck by 24 musket balls.[30] Armed only with swords and faced with the overwhelming firepower of Patriot muskets and artillery, the Highland Scots retreated. The surviving elements of Campbell's company got back over the bridge, and the governor's force dissolved and retreated.[31]

Capitalising on the success, the Revolutionary forces quickly replaced the bridge planking and gave chase. One enterprising company led by one of Caswell's lieutenants forded the creek above the bridge, flanking the retreating loyalists. Colonel Moore arrived on the scene a few hours after the battle. He stated in his report that 30 loyalists were killed or wounded, "but as numbers of them must have fallen into the creek, besides more that were carried off, I suppose their loss may be estimated at fifty."[29] The Revolutionary leaders reported one killed and one wounded.[29][30]

Aftermath

Over the next several days, the North Carolina Provincial Congress' militia force mopped up the fleeing loyalists. In all, about 850 men were captured. Most of these were released on parole, but the ringleaders were sent to Philadelphia as prisoners.[29] Despite very hard feelings on both sides, the Loyalist prisoners were treated with respect. This helped convince many not to take up arms again. [32]

Among those who survived to be taken prisoner was the Loyalist war poet Iain mac Mhurchaidh (John Macrae), a member of Clan Macrae, recent immigrant from Kintail, and important figure in Scottish Gaelic literature. The poet's son, Murdo Macrae, also fought on the Loyalist side during the battle and was mortally wounded.[33][34]

Combined with the capture of the loyalist camp at Cross Creek, the patriots confiscated 1,500 muskets, 300 rifles, and $15,000 (as valued at the time) of Spanish gold.[35] Many of the weapons were probably hunting equipment, and may have been taken from people not directly involved in the loyalist uprising.[36] The action had a galvanizing effect on patriot recruiting, and the arrests of many loyalist leaders throughout North Carolina cemented patriot control of the state. A pro-patriot newspaper reported after the battle, "This, we think, will effectually put a stop to loyalists in North Carolina".[32]

The battle had significant effects among the Scottish Gaels of North Carolina, where loyalist sympathisers refused to take up arms whenever recruitment efforts were made later in the war, and those who did were routed out of their homes by the pillaging activities of their patriot neighbors.[35]

When news of the battle reached London, it received mixed commentary. One news report minimised the defeat since it did not involve any regular army troops, while another noted that an "inferior" patriot force had defeated the loyalists.[35] Lord George Germain, the British official responsible for managing the war in London, remained convinced in spite of the resounding defeat that loyalists were still a substantial force to be tapped.[32]

The expedition that the loyalists had been planning to meet was significantly delayed, and did not depart Cork, Ireland until mid-February. The convoy was further delayed and split apart by bad weather, so the full force did not arrive off Cape Fear until May 1776.[37] As the fleet gathered, North Carolina's provincial congress met at Halifax, North Carolina, and in early April passed the Halifax Resolves, authorizing the colony's delegates to the Continental Congress to vote in favor of declaring independence from the British Empire.[38] General Clinton used the force in an attempt to take Charleston, South Carolina. His attempt, at the Battle of Sullivan's Island, failed and it represented the last significant British attempts to retake control of the southern colonies until late 1778.[39]

A Pro-Patriot newspaper in Virginia angrily condemned Bridadier-General MacDonald by pointing out that King George III, whom he now served, came from the very dynasty that MacDonald had once considered usurpers and tried to depose during the Jacobite rising of 1745. Yet, as the newspaper pointed out, Brigadier General MacDonald now viewed American Patriots as rebels and traitors against their, "lawful King." Ironically, the Crown ultimately showed the Brigadier-General little or no appreciation.

While he was held as a POW in Philadelphia, efforts to negotiate a prisoner exchange for Brigadier General Donald MacDonald, were always hampered afterwards; as the British Army refused to accept MacDonald's promotion by Governor Josiah Martin from Major to Brigadier General, and the Continental Congress refused to authorize George Washington to exchange MacDonald for a captured Patriot officer of lower than Brigadier General's rank.

Meanwhile, General MacDonald's son, a fellow Jacobite veteran of the 1745 uprising who was also named Donald MacDonald, joined the Patriot side very soon after his father was taken prisoner following the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge. According to historian J.P. MacLean, "The son was a remarkably stout, red-haired young Scotsman, cool under the most trying difficulties and brave without a fault."[40]

MacDonald attained the rank of Sergeant and, "was the subject of many tales of daring exploits".[41]

When asked by his commanding officer, General Peter Horry, however, why he had abandoned his father's party and joined "the rebels", Sgt. MacDonald replied,

Immediately on the misfortune of my father and his friends at the Great Bridge, I fell to thinking what could be the cause; and then it struck me that it must have been owing to their own monstrous ingratitude. 'Here now', I said to myself, 'is parcel of people, meaning my poor father and his friends, who fled from the murderous swords of the English after the massacre at Culloden. Well, they came to America with hardly anything but their poverty and their mournful looks. But among this friendly people that was enough. Every eye that saw us, had pity; and every hand was reached out to assist. They received us in their homes as though they had been their own unfortunate brothers. They kindled high their hospitable fires for us, and bade us eat and drink and banish our misfortunes, for that we were in a land of friends. And so indeed, we found it; for whenever we told of the woeful Battle of Culloden, and how the English gave no quarter to our unfortunate countrymen, but butchered all they could overtake, these generous people often gave us their tears, and said, 'O! That we had been there to aid with our rifles, then should many of those monsters have bit the ground!' They received us into the bosoms of their peaceful forests, and gave us their lands and their beauteous daughters in marriage, and we became rich. And yet, after all, when the English came to America to murder this innocent people, merely for refusing to be their slaves, then my father and friends, forgetting all the Americans had done for them, went and joined the British, to assist them to cut the throats of their best friends! 'Now', I said to myself, 'if ever there was a time for God to stand up and punish ingratitude, this was the time.' And God did stand up; for he enabled the Americans to defeat my father and his friends most completely. But instead of murdering the prisoners as the English had done at Culloden, they treated us with their usual generosity. And now these are the people I love and will fight for as long as I live."[42]

As related in General Horry's memoirs, Sgt. MacDonald once posed as a British Legion soldier and asked a Loyalist plantation owner to give up his best stallion for Lieut.-Col. Banastre Tarleton's personal use. Overjoyed, the planter handed Sgt. MacDonald a pedigreed stallion named Selim, which the Sergeant always rode in later years. Furthermore, when the planter visited Tarleton's camp to ask the Lietenant-Colonel how he liked his new mount, the response of both men to the realization that they had been had is best described as unprintable.[43]

Sergeant MacDonald was serving under General Francis Marion when he was killed in action during the Siege of Fort Motte on May 12, 1781. According to historian J.P. MacLean, "His resting place is unknown. No monument has been erected to his memory; but his name will endure so long as men shall pay respect to heroism and devotion to country."[44]

After the battle, Flora MacDonald was interrogated by the North Carolina Committee of Safety, before which she exhibited "spirited behavior." Soon afterwards, however, Flora experienced the deaths of all her children during a typhus epidemic. At her imprisoned husband's urging, Flora MacDonald set out to return in 1779 from North Carolina to her native village of Milton, South Uist. With the assistance of a sympathetic Patriot officer named Captain Ingrahm, MacDonald was granted a passport allowing her to cross the lines and take passage aboard a ship from British-held Charleston, South Carolina for Halifax, Nova Scotia. MacDonald continued facing severe trials, which included having her left arm broken during an attack by a French privateer upon the ship aboard which she was later returning to Scotland. In the end, Flora arrived safely and her brother built her a cottage to live in at Milton.

In 1781, when General Charles Cornwallis passed through the Cross Creek area, he reported that "[m]any of the inhabitants rode into camp, shook me by the hand, said they were glad to see us and that we had beat Greene and then rode home."[45]

Following the end of the war, many regions of North Carolina which had been mainly settled by Scottish Gaels, were almost depopulated, as Gaelic-speaking Loyalists fled northward towards what remained of British North America.[46]

Similarly to Brigadier General MacDonald, however, Allan and Flora MacDonald found the race of the Georges very unappreciative for their sufferings. As the Crown refused to fully reimburse them for the confiscation of 'Killegray', their slave plantation in Anson County, North Carolina, Allan and Flora MacDonald lacked the financial means to resettle in Canada and were forced to return to Scotland. Flora always said in her later life that she first served the House of Stuart and then the House of Hanover and that she was worsted in the cause of each. Flora MacDonald died on March 5, 1790.[47]

According to Marcus Tanner, despite the post-Revolutionary War flight of many local United Empire Loyalists and the subsequent redirection of Scottish Highland emigration to Canada, a large Gàidhealtachd community continued to exist in North Carolina, "until it was well and truly disrupted", by the American Civil War.[48]

Even so, local pride in the Scottish heritage of local pioneers remains very a part of the Culture of North Carolina. One of North America's largest Highland games events, the Grandfather Mountain Highland Games, are held there every year and draw in visitors from all over the world. The Grandfather Mountain games have been called "the best" such event in the United States because of the spectacular landscape and the large number of people who attend in kilts and other regalia of the Scottish clans. It is also widely considered to be the largest "gathering of clans" in North America, as more family lines are represented there than any other similar event.

The Moore's Creek Bridge battlefield site was preserved in the late 19th century through private efforts that eventually received state financial support. The Federal government took over the battle site as a National Military Park operated by the War Department in 1926. The War Department operated the park until 1933, when the National Park Service took over the site as the Moores Creek National Battlefield.[49] It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.[50] The battle is commemorated every year during the last full weekend of February.[51]

Order of battle

Early accounts of the battle often misstated the size of both forces involved in the battle, typically reporting that 1,600 loyalists faced 1,000 patriots. These numbers are still used by the National Park Service.[52]

North Carolina

The patriot forces were also underreported since Caswell apparently casually grouped the ranger forces of John Ashe as part of Lillington's company in his report.[29]

The Provincial Congress' militia forces order of battle included a mix of North Carolina Minutemen and Militia units. Because of the performance of the local militia and the higher costs of Minutemen, the North Carolina General Assembly abandoned the use of Minutemen on April 10, 1776 in favor of local militia brigades and regiments. The following units participated in this battle:[53]

- New Bern District Minutemen Battalion, 13 companies

- Wilmington District Minutemen Battalion, 4 companies

- Halifax District Minutemen Battalion, 5 companies

- Hillsborough District Minutemen Battalion, 7 companies

- 1st Salisbury District Minutemen Battalion, 1 company

- 2nd Salisbury District Minutement Battalion, 11 companies

- 1st North Carolina Regiment, 7 companies

- Halifax District Brigade

- Halifax County Regiment, 1 company

- Northampton County Regiment, 1 company

- Hillsborough District Brigade

- Chatham County Regiment, 4 companies

- Granville County Regiment, 1 company

- Orange County Regiment, 1 company

- Wake County Regiment, 4 companies

- New Bern District Brigade

- Craven County Regiment, 4 companies

- Dobbs County Regiment, 8 companies

- Johnston County Regiment, 5 companies

- Pitt County Regiment, 4 companies

- Salisbury District Brigade

- Anson County Regiment, 2 companies

- Guilford County Regiment, 12 companies

- Surry County Regiment, 3 companies

- Tryon County Regiment, 8 companies

- Wilmington District Brigade

- Bladen County Regiment, 8 companies

- Brunswick County Regiment, 1 company

- Cumberland County Regiment, 2 companies

- Duplin County Regiment, 10 companies

- Onslow County Regiment, 3 companies

- New Hannover County Regiment, 2 companies of volunteer independent rangers

Great Britain

Historian David Wilson, however, points out that the large loyalist size is attributed to reports by General MacDonald and Colonel Caswell. MacDonald gave that figure to Caswell, and it represents a reasonable estimate of the number of men starting the march at Cross Creek. Alexander Mclean, who was present at both Cross Creek and the battle, reported that only 800 loyalists were present at the battle, as did Governor Martin.

References

- Wilson, p. 34

- Wilson, p. 35

- Russell, p. 80

- Russell, p. 79

- Meyer, p. 140

- Fryer, p. 118

- Fryer, pp. 121–122

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 60.

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Pages 60-61.

- Demond, p. 91

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 60.

- Meyer, p. 142

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 61.

- Wilson, p. 23

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 62.

- Michael Newton (2001), We're Indians Sure Enough: The Legacy of the Scottish Highlanders in the United States, Saorsa Media, pg. 32.

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 55.

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 62.

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 62.

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 199.

- Michael Newton (2015), Seanchaidh na Choille The Memory Keeper of the Forest: Anthology of Scottish Gaelic Literature of Canada, Cape Breton University Press. Page 468.

- Edited by Natasha Sumner and Aidan Doyle (2020), North American Gaels: Speech, Song, and Story in the Diaspora, McGill-Queen's University Press. Page 297.

- Wilson, p. 28

- Russell, p. 81

- North Carolina in the American Revolution by Hugh F. Rankin pg. 101–103, 1959 – ISBN 9780865260917

- Wilson, p. 26

- Wilson, p. 27

- Russell, p. 82

- Wilson, p. 30

- The American Revolution: A Visual History. DK Smithsonian. p. 107.

- Wilson, p. 29

- Wilson, p. 33

- Michael Newton (2001), We're Indians Sure Enough: The Legacy of the Scottish Highlanders in the United States, Saorsa Media, pg. 141.

- "MacRae, John | NCpedia". www.ncpedia.org.

- Russell, p. 83

- Wilson, p. 31

- Russell, p. 85

- Russell, p. 84

- Wilson, p. 56

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 204.

- Michael Newton (2001), We're Indians Sure Enough: The Legacy of the Scottish Highlanders in the United States, Saorsa Media. Page 117.

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Pages 204-205.

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 205-206.

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 207.

- Demond, p. 137

- Michael Newton (2001), We're Indians Sure Enough: The Legacy of the Scottish Highlanders in the United States, Saorsa Media. Page 143.

- J.P. MacLean (1900), An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America, Cleveland, Ohio. Page 199.

- Marcus Tanner (2004), The Last of the Celts, page 289.

- Capps and Davis

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Moores Creek National Battlefield – Things to do". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- "Moores Creek National Battlefield website". National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- Lewis

Sources

- Capps, Michael A.; Davis, Stephen A (1999). "Moores Creek National Battlefield – Administrative History". National Park Service. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- Demond, Robert O (1979) [1940]. The Loyalists in North Carolina During the Revolution. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8063-0839-5. OCLC 229188174.

- Fryer, Mary Beacock (1987). Allan Maclean, Jacobite General: the Life of an Eighteenth Century Career Soldier. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-011-3. OCLC 16042453.

- Greene, Jack P. (February 2000). "The American Revolution". American Historical Review. 1. 105 (1): 91–102. doi:10.2307/2652437. JSTOR 2652437.

- Lewis, J.D. "Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge". The American Revolution in North Carolina. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- Meyer, Duane (1987) [1961]. The Highland Scots of North Carolina, 1732–1776. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4199-0. OCLC 316095450.

- Murray, Aaron (2004). The American Revolution Battles and Leaders. New York: DK Publishing. pp. 30–31.

- Purcell, L. Edward & Sarah J. (2000). Encyclopedia of Battles in North America 1517 to 1916. New York: Facts on File Inc. p. 187.

- Russell, David Lee (2000). The American Revolution in the Southern Colonies. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0783-5. OCLC 44562323.

- Wilson, David K (2005). The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-573-3. OCLC 56951286.

Further reading

- "The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge," Revolutionary North Carolina, a digital textbook produced by the UNC School of Education.