Battle of Pasir Panjang

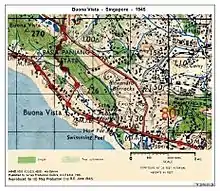

The Battle of Pasir Panjang, which took place between 13 and 15 February 1942, was part of the final stage of the Empire of Japan's invasion of Singapore during World War II. The battle was initiated upon the advancement of elite Imperial Japanese Army forces towards Pasir Panjang Ridge on 13 February.

| Battle of Pasir Panjang | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Singapore in the Pacific theatre of World War II | |||||||

Pasir Panjang Pillbox | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,400 infantry | 13,000 infantry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 159 killed and hundreds wounded | Hundreds killed and several hundreds more wounded. | ||||||

13,000 Japanese troops had made an amphibious landing in northwestern Singapore near Sarimbun (see Battle of Sarimbun Beach) and had started to advance south towards Pasir Panjang. They had already captured Tengah Airfield en route. The 13,000 soldiers[1] constituted a significant part of the total strength of 36,000 Japanese troops deployed in the invasion of Singapore.

Preparations

The 1st Malaya Infantry Brigade, comprising the British 2nd Loyal Regiment under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Mordaunt Elrington, together with the 1st Malaya Regiment commanded by Lieutenant Colonel J.R.G. Andre, consisted of less than three sections of the Mortar Platoon, Anti-Aircraft Platoon along with the Bren Gun Carrier Platoon under Captain R.R.C. Carter, all of which were held in reserve. These units were tasked with defending the approach to Pasir Panjang Ridge, also known as "The Gap".[2] The 44th Indian Brigade were positioned on their right flank.

A Malay platoon, consisting of 42 soldiers and their officers, commanded by Second Lieutenant Adnan Saidi, was holding a critical part of the British defences at Bukit Chandu. Adnan and his men would take the brunt of the Japanese assault shortly after.

Battle

The first battle between the Malay Regiment and Japanese soldiers occurred on 13 February at around 1400 hours. The Japanese 18th Division started to attack the southwestern coast along Pasir Panjang Ridge and astride Ayer Rajah Road. The Japanese 56th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Yoshio Nasu, supported by a considerable force of artillery, attacked the ridge during the morning.

One of the units defending the line was B Company of the Malay Regiment. Under heavy fire from the Japanese, who had artillery and tank support, B Company was forced to retreat to the rear. However, before the retreat could be completed, the Japanese succeeded in breaking through B Company's position. In the battle, the troops fought hand-to-hand combat using bayonets against the Japanese. A few from B Company managed to save themselves while others were captured as prisoners-of-war. This penetration led to the withdrawal after dark, of both the 44th Indian and 1st Malay Brigade, to the general line at Mount Echo (junction of Ayer Rajah and Depot Road, around present-day Buona Vista).

Bukit Chandu

On 14 February, the eve of Chinese New Year, the Japanese again launched a large-scale attack at 0830 hours with heavy support by intense mortar bombardment and artillery gunfire, on the battlefront held by the 1st Malay Brigade.[3] The defenders managed to beat this off and a number of other attacks, despite suffering considerable casualties. The fighting also included bitter hand-to-hand combat and losses on the Japanese side were as heavy as their Malay foes. At 1600 hours, another attack, this time also supported by tanks, eventually succeeded in penetrating the left flank and the defenders on this side were forced back to a line running from the junction of Ayer Rajah Road to Depot Road through to Alexandra Brickworks and along the canal leading to Bukit Chermin further southeast. Owing to the failure of units on both of its flanks to hold their ground, the 1st Malay Brigade had to withdraw at 1430 hours the following day. It was at this point that C Company of the Malay Regiment received instructions to move to a new defence position sited at Bukit Chandu.

Bukit Chandu (meaning "Opium Hill" in Malay) was so named after an opium-processing factory located at the foot of the hill. This was also where C Company of the Malay Regiment made their final stand against the imminent Japanese attack. Bukit Chandu was a key strategic defence position for two important reasons. Firstly, it was situated on high ground overlooking the island to the northwest and secondly, if the Japanese gained control of the ridge, it gave them direct passage to the Alexandra area just behind. The British military in Singapore had its main ammunition bases and supply depots, one of their military hospitals (Alexandra Hospital) and other key installations (such as the Normanton Oil Depot) located right next to Alexandra.

C Company's position was separated from D Company by a big canal. Oil was burning in the canal, which flowed from the bombed-out and severely-destroyed Normanton Oil Depot. The burning oil in the canal prevented C Company's soldiers from retreating further. The company was under the command of Second Lieutenant Adnan Bin Saidi. He encouraged his men to defend Bukit Chandu to the last soldier, and was killed[4][5] together with many of his fellow soldiers in the last desperate defensive battle at Pasir Panjang.

The Japanese military pressed on their attack on Bukit Chandu in the afternoon, but this time they did so under the guise of a deception attempt. They sent a group of their soldiers, dressed in captured British Indian troops' uniforms (with their faces and skin smeared with dirt and soot and the wearing of turbans to pass off as Punjabis), to present themselves as allied Indian soldiers in the British Indian Army. C Company saw through this trick as they knew that soldiers of the British Army typically marched in a line of three columns while the supposed Punjabi soldiers in front of their lines were moving in a line of four columns. When they reached the Malay Regiment's defensive line, C Company's troops opened fire, killing 22 disguised Japanese soldiers and wounding many others. Those who survived escaped downhill back to friendly lines.

Last stand

Two hours later, the Japanese forces launched an all-out banzai charge in great numbers in an attempt to wipe out the Malay troops ahead through sheer numbers and over-arching strength. The attack, conducted again with artillery shelling and tank support, overwhelmed the Malay Regiment and the defence line eventually broke. Despite being greatly outnumbered and short of ammunition (with only a few grenades at hand and not many rounds for their machine guns and rifles left) and much-needed combat supplies (including medication and bandages), the Malay Regiment continued to resist the Japanese. Both sides engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat as well as using bayonets. Adnan was seriously wounded but refused to retreat or surrender and instead encouraged his men to fight to the end.[6]

Soon after, with the whole area of Pasir Panjang falling under Japanese control, Adnan, who was badly wounded and unable to fight, was captured. Instead of taking him prisoner, the Japanese continuously kicked, punched and beat him before tying him to a tree and stabbing him to death with their bayonets (some sources claim that Adnan was brutally beaten up before being thrown into a tied-up gunny sack, which was then stabbed repeatedly by his Japanese captors, while others indicate that they stabbed him to death before hanging him upside down from a tree).[7]

Casualties

During the entire Malayan Campaign, but mostly from 13 to 15 February 1942 in Singapore, the Malay Regiment suffered a total of 159 killed. Six of them were British officers, seven Malay officers, 146 other ranks and a large but unspecified number wounded. About 600 surviving Malay Regiment soldiers reassembled in the Keppel Golf Link area. Here, they were separated from their British officers. They later joined prisoners-of-war from the British Indian Army battalions at the Farrer Park concentration area. It remains unclear as to how many casualties the Japanese suffered.

Aftermath

The battle of Pasir Panjang had little strategic significance. From a purely military operational perspective, the Battle of Pasir Panjang could not change the outcome of the fate of Singapore and it was a matter of time before the British would surrender to the Japanese 25th Army. The Allied units stationed there were simply tasked with defending the approach to the ridge, but instead had to resist the main invasion force. Bukit Chandu itself is situated on high ground overlooking the island to the north, and it controlled the direct passage to the Alexandra area where the British army had its main ammunition and supply depots, military hospital and other key installations. The fall of Bukit Chandu allowed Japan access to the Alexandra area, indirectly contributing to the Alexandra Hospital massacre.

Adnan Saidi is described by many Singaporeans and Malaysians today as a hero for his actions on Bukit Chandu – he encouraged his men not to surrender and instead fight to the death. In Singaporean and Malaysian school textbooks, he is also credited as the soldier who noticed the error in the marching style of the Japanese soldiers disguised as Indian troops.

Fighting continued after his death and the subsequent British signing of surrender of Singapore to the Empire of Japan at 1810 hours on 15 February 1942 in the area around Alexandra Hospital, Tanjong Pagar and Pulau Belakang Mati (Sentosa) where some of the Malay Regiments regrouped.

The Malay Regiment showed what esprit de corps and discipline can achieve. Garrisons of posts held their ground and many of them were wiped out almost to a man.

On 10 February 2021, it was reported that on the day before, 100-year-old Ujang Mormin, the last of the survivors of the battle at Pasir Panjang and then a private of the Malay Regiment, had passed away in a hospital in Selangor, Malaysia due to the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. Ujang had been 21 years old when he fought the Japanese.[11]

See also

References

- Richmond, Simon (19 May 2010). Malaysia, Singapore & Brunei. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781741048872 – via Google Books.

- Langley, Michael (19 May 1976). The Loyal Regiment (North Lancashire): (The 47th and 81st Regiments of Foot). Cooper. ISBN 9780850520750 – via Google Books.

- Donald J. Young (2014). Final Hours in the Pacific: The Allied Surrenders of Wake Island, Bataan, Corregidor, Hong Kong and Singapore. McFarland. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-7864-6231-5.

- "File Not Found". www.mindef.gov.sg. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- "bosmalay4.html". www.oocities.org.

- Farrell, Brian P. (19 May 2006). The Defence and Fall of Singapore 1940-1942. Tempus. ISBN 9780752437682 – via Google Books.

- "The Malay regiment". Web.singnet.com.sg. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Karl Hack; Kevin Blackburn (2012). War Memory and the Making of Modern Malaysia and Singapore. NUS Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-9971-69-599-6.

- Donald J. Young (2014). Final Hours in the Pacific: The Allied Surrenders of Wake Island, Bataan, Corregidor, Hong Kong and Singapore. McFarland. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-7864-6231-5.

- Charles Whiting (1987). Poor Bloody Infantry. Stanley Paul. ISBN 978-0-09-172380-4.

- "Private Ujang Mormin, last survivor of Battle of Pasir Panjang during WWII, dies due to Covid-19". The Straits Times. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.