Battle of Pensacola (1814)

The Battle of Pensacola (7-9 November 1814) was a battle of the Creek War during the War of 1812, in which American forces fought against forces from the kingdoms of Britain and Spain who were aided by the Creek Indians and African-American slaves allied with the British.[4] General Andrew Jackson led his infantry against British and Spanish forces controlling the city of Pensacola in Spanish Florida. Allied forces abandoned the city, and the remaining Spanish forces surrendered to Jackson.

| Battle of Pensacola | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

Jackson and his troops entering Pensacola on November 6, 1814 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Creek Native Americans | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,000 infantry |

British: 100 infantry from Royal Marines, Red Sticks and Royal Marine Artillery[1][2] Unknown artillery and black slaves 1 fort 1 coastal battery Spanish: 500 infantry Unknown artillery 1 fort Creek: Unknown warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~7 killed and 11 wounded[3] | ~15 killed or wounded | ||||||

The battle was the only engagement of the war to take place within the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Spain, which was angered by the rapid withdrawal of British forces. Britain's naval squadron of five warships also withdrew from the city.[5][6]

Background

Horseshoe Bend

Many refugees fled to Spanish West Florida after the Red Stick Creeks were defeated at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. The presence of the Creek refugees had motivated British Brevet Captain George Woodbine of the Royal Marines to travel to Pensacola in July 1814.[7] Woodbine's liaisons with the refugees and the Spanish governor of Pensacola enabled the British to maintain a military presence at Pensacola from August 23, 1814,[8] initially occupying Fort San Miguel[9] and the town itself. British relations deteriorated with the Spanish governor,[10] so the British force left the town and consolidated in the outlying Fort San Carlos and at the Santa Rosa Punta de Siguenza battery (later rebuilt as Fort Pickens).[11]

Gordon's expedition

The armed Creeks at Horseshoe Bend prompted Jackson to send Tennessee militia Captain John Gordon to reconnoiter Pensacola and see if the British were using it as a base to arm Indians hostile to the United States. Gordon arrived at Pensacola to find the Union Jack flying at the fort and British officers training and arming Creek warriors.[12] Gordon's son-in-law Felix Zollicoffer wrote of the excursion:

It was Capt. Gordon who performed that memorable and perilous service of penetrating alone a forest 300 miles from Hickory Grounds to Pensacola, encountering and evading various Indian parties, and procuring for Gen. Jackson that valuable knowledge of Spanish fortifications and of the Spanish complicity with British and Indian enemies which at once determined him upon and gave him the key to the famous capture of Pensacola.[13]

Jackson decided to attack Pensacola based upon Gordon's report.

Preparations at Pensacola

General Jackson planned to drive the British from Pensacola in Spanish Florida, then march to New Orleans to defend the city against any British attack.[14] His forces had been diminished due to desertions,[1] so he was forced to wait for Brigadier General John Coffee and his volunteers before moving against the city. Jackson and Coffee met at Pierce's Stockade in Alabama.[15] Jackson assembled a force of up to 4,000 men;[3] he moved out towards Pensacola on November 2 and reached it on November 6.[16] The forces in the Anglo-Spanish fort consisted of around 100 British infantry and a coastal battery, about 500 Spanish infantry, an unknown number of British and Spanish artillery, and an unknown number of Creek warriors. Jackson first sent Major Henri Piere as a messenger under a white flag of truce to Spanish Governor Mateo González Manrique. However, the messenger approached the city and was fired upon by the garrison in Fort San Miguel. Jackson then sent a second messenger, this time a Spaniard,[17] and offered to garrison the forts with Americans, who would hold them until relieved by Spanish troops; this would ensure Spain's neutrality in the conflict. Manrique rejected the offer.[10]

Battle

At dawn, Jackson had 3,000 troops marching on the city.[16] The Americans flanked the city from the east to avoid fire from the forts and marched along the beachfront,[18] but the sandy beach made it difficult to move up the artillery. The attack went ahead nonetheless and was met with resistance in the center of town by a line of infantry supported by a battery. However, the Americans charged and captured the battery.[18]

Governor Manrique appeared with a white flag and agreed to surrender on any terms Jackson put forward if only he would spare the town. Fort San Miguel was surrendered on November 7, but Fort San Carlos, which lay 14 miles to the west, remained in British hands.[19]

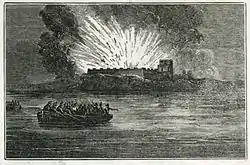

Jackson planned to capture the fort by storm the next day, but it was blown up and abandoned before Jackson could move on it and the remaining British withdrew from Pensacola[20] along with the British squadron (comprising HMS Sophie (18 guns), HMS Childers (18 guns; Capt. Umfreville), HMS Seahorse (38 guns; Capt. Gordon), HMS Shelburne (12 guns) and HMS Carron (20 guns; Capt. Spencer).[21] A number of Spanish accompanied the retreating British forces[22][23][24][25][26][27] and did not return to Pensacola until 1815.[28][29][30]

Aftermath

The battle had forced the British out of Pensacola and left the Spanish in control, angered by the British, who had fled in such a hurry once Jackson's force had attacked, for their destruction of the fortifications and the removal of part of the Spanish garrison.[31] Jackson suspected the squadron which had left Pensacola harbor would return to strike at Mobile, Alabama.[32] Jackson abandoned Pensacola to the Spanish and set out to Mobile, and upon reaching the town[11] he received requests to hurry to the defense of New Orleans.[21] American casualties were negligible; around seven dead and eleven wounded. (Two officers and nine enlisted men wounded are documented by Eaton.[33]) The Spanish and British suffered at least 15 dead or wounded.[3] Lieutenant Colonel Edward Nicolls states there were no deaths among the British, and is of the opinion that the Americans suffered 15 fatalities and numerous casualties.[34][35]

Four active infantry battalions of the Regular Army (1-1 Inf, 2-1 Inf, 2-7 Inf and 3-7 Inf) perpetuate the lineages of American units (elements of the old 3rd, 39th and 44th Infantry Regiments) that were at the Battle of Pensacola.[36][37][38][39]

See also

Notes

- Heidler, p45

- Nicolas, p289 states 60 Marine infantry, 180 Red Sticks and 12 Royal Marine Artillery

- Tucker (ed), p570

- "Colonial Period" Aiming for Pensacola: Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers. Retrieved 2016-10-25.

- Hyde, p97

- Sugden, p296

- "Documents Relating to Colonel Edward Nicholls and Captain George Woodbine in Pensacola, 1814". The Florida Historical Society Quarterly. 10 (1): 51–54. 1931-01-01. JSTOR 30150119.

- Marshall, p65

- Mahon, p347

- Tucker (ed), p245

- Tucker (ed), p569

- "Captain John Gordon, of the spies". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- "Captain John Gordon, of the spies". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- Tucker (ed), p341

- Paterson, p163

- Eaton, p145

- Eaton, p146

- Eaton, p148

- Eaton, p149

- Eaton, p151

- Heidler, p46

- Heidler, p47

- ADM 37/4636 HMS Childers ship muster. 102 Spaniards embarked, 'by order of Capt Jordan'

- ADM 37/4795 HMS Sophie ship muster. 149 Spanish subsequently disembarked at St Joseph's Bay on 30 November 1814

- ADM 37/5438 HMS Seahorse ship muster. Embarked: 4x Indian warriors (1211 to 1215 in the muster), Spaniards (1170 to 1206)

- ADM 37/4960 HMS Shelburne ship muster. Embarked: Spaniards (41 to 83)

- ADM 37/5250 HMS Carron ship muster. Embarked: Spaniards (193 to 224)

- "Documents Relating to Colonel Edward Nicholls and Captain George Woodbine in Pensacola, 1814". Florida Historical Quarterly: 52. July 1931.

Cochrane's letter to Manrique, composed on the Tonnant, off Mobile 10 February 1815 does state: 'Sorry that it has not been in my power to bring back the Spanish Soldiers from that vicinity ...., but in a few days I will dedicate a Sloop of War Solely to that purpose' The original transcript is stored within: Letters from Commander-in-Chief, North America: 1815, nos. 1–126 (ADM 1/508)

- Letter from Admiral Cochrane to Admiral Malcolm composed on the Tonnant, off Mobile 17 February 1815 'The Spanish Governor at Pensacola, having requested that a part of the Spanish Troops removed to the Bluff, when the American Army attacked ...you will send a troop ship to Appalachicola to receive them on board, and land them in the harbour of Pensacola'. This is within WO 1/143 folio 19, which can be downloaded for a fee from the UK National Archives website

- Sugden, p296

- Hyde, p97

- Eaton, p152

- Eaton 2013, p. 28.

- Historical Record of the Royal Marine Forces. Vol. 2. London: JThomas & William Boone. 1845. p. 290.

[Nicolls] retreated from the place, and with such ability as to preserve his stores, causing an [estimated] loss to the enemy of 15 killed, some officers and many wounded; and this service was performed by 700 men, in the face of the American army of 5,000 men, with five pieces of cannon

- The primary source used by Nicolas is a letter from Edward Nicolls to Lord Bathurst dated 5 May 1817, UK National Archives reference WO 1/344, folio 421. '[We] retreated fighting from the place without the loss of a man... and causing a loss to the enemy of 15 killed and some officers & privates wounded in the face of 5000 men and 5 pieces of cannon, with only 700 men [of the Anglo-Spanish force]' The purpose of the letter was for Nicolls to be reimbursed for expenses in relation to Nicolls entertaining the Creek indians.

- "Lineage And Honors Information - 1st Battalion, 1st Infantry Lineage". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

- "Lineage And Honors Information - 2d Battalion, 1st Infantry Lineage". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

- "Lineage And Honors Information - 2d Battalion, 7th Infantry Lineage". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

- "Lineage And Honors Information - 3d Battalion, 7th Infantry Lineage". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

References

- Eaton, John Henry; Reid, John (1828). The life of Major General Andrew Jackson. McCarty & Davis.

- Eaton, Joseph H. (2013) [1851]. "Film reel M1832, 1 roll. ARC ID: 1184633.". Returns of Killed and Wounded in Battles or Engagements with Indians and British and Mexican Troops, 1790–1848. Record Group 94: Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1762 - 1984. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- Heidler, David Stephen & Jeanne T (2003): Old Hickory's War: Andrew Jackson and the Quest for Empire. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2867-1

- Hyde, Samuel C. (2004): A Fierce and Fractious Frontier: The Curious Development of Louisiana's Florida Parishes, 1699–2000. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0807129232

- Mahon, John K. (1991): The War Of 1812. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306804298

- Marshall, John (1829): Royal Naval Biography. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

- Millett, Nathaniel (2005). "Britain's 1814 Occupation of Pensacola and America's Response: An Episode of the War of 1812 in the Southeastern Borderlands". Florida Historical Quarterly. 84 (2): 229–255. JSTOR 30149989.

- Nicolas, Paul Harris (1845): Historical Record of the Royal Marine Forces. Volume 2, 1805–1842

- Patterson, Benton Rains (2008), The Generals, Andrew Jackson, Sir Edward Pakenham, and the road to New Orleans, New York: New York University Press, ISBN 978-0-8147-6717-7

- Sugden, John (January 1982). "The Southern Indians in the War of 1812: The Closing Phase". Florida Historical Quarterly. 60 (3): 300. JSTOR 30146793.

- Tucker, Spencer (ed). (2012): The Encyclopedia of the War of 1812: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1851099565