Battle of Pinkie

The Battle of Pinkie, also known as the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh (English: /klʌf/ KLUF, Scots pronunciation: [kl(j)ux]),[5] took place on 10 September 1547 on the banks of the River Esk near Musselburgh, Scotland. The last pitched battle between Scotland and England before the Union of the Crowns, it was part of the conflict known as the Rough Wooing and is considered to have been the first modern battle in the British Isles. It was a catastrophic defeat for Scotland, where it became known as "Black Saturday".[6] A highly detailed and illustrated English account of the battle and campaign authored by an eyewitness William Patten was published in London as propaganda four months after the battle.[7]

| Battle of Pinkie | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Rough Wooing | |||||||

River Esk and Inveresk Church at Musselburgh | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 18,000 to 22,000[1] |

c. 30 warships 16,800 men[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

7,000–8,000 killed, wounded or captured [3] | 200–600 killed or wounded[4] | ||||||

| Designated | 21 March 2011 | ||||||

| Reference no. | BTL15 | ||||||

Battle location in Scotland | |||||||

Background

In the last years of his reign, King Henry VIII of England tried to secure an alliance with Scotland by the marriage of the infant Mary, Queen of Scots, to his young son, the future Edward VI. When diplomacy failed, and Scotland was on the point of an alliance with France, he launched a war against Scotland that has become known as the Rough Wooing. The war also had a religious aspect; some Scots opposed an alliance that would bring religious Reformation on English terms. During the battle, the Scots taunted the English soldiers as "loons" (persons of no consequence. A “loon” in Scots and Doric is a male child), "tykes" and "heretics".[8] The Earl of Angus, who is said to have arrived with monks "the professors of the Gospel", the heavy pikemen of the Lowlands, eight thousand strong, was in the lead.[9]

When Henry VIII died in 1547, Edward Seymour, maternal uncle of Edward VI, became Lord Protector and Duke of Somerset, with (initially) unchallenged power. He continued the policy of seeking forcible alliance with Scotland by demanding both the marriage of Mary to Edward, and the imposition of an Anglican Reformation on the Scottish Church. Early in September, he led a well-equipped army into Scotland, supported by a large fleet.[10] The Earl of Arran, Scottish Regent at the time, was forewarned by letters from Adam Otterburn, his representative in London, who had observed English war preparations.[11] Otterburn may have seen the leather horse armour designed and made by the workshop of the Italian artist Nicholas Bellin of Modena at Greenwich.[12]

Campaign

Somerset's army was partly composed of the traditional county levies, summoned by Commissions of Array and armed with longbow and bill as they had been at the Battle of Flodden, thirty years before. However, Somerset also had several hundred German mercenary arquebusiers, a large and well-appointed artillery train, and 6,000 cavalry, including a contingent of Spanish and Italian mounted arquebusiers under Don Pedro de Gamboa.[13] The cavalry were commanded by Lord Grey of Wilton, as High Marshal of the Army, and the infantry by the Earl of Warwick, Lord Dacre of Gillesland, and Somerset himself.[13] William Patten, an officer of the English army, recorded its numbers as 16,800 fighting men and 1,400 "pioneers" or labourers.[2]

Somerset advanced along the east coast of Scotland to maintain contact with his fleet and thereby keep in supply. Scottish border reivers harassed his troops but could impose no major check to their advance.[14] The English captured and slighted Innerwick Castle and Thornton Castle.[15] He camped at Longniddry on 7 September.[16]

Far to the west, a diversionary English invasion of 5,000 men was led by Thomas Wharton and the Scottish dissident Earl of Lennox. On 8 September they took Castlemilk in Annandale and burnt Annan after a bitter struggle to capture its fortified church.[17]

To oppose the English south of Edinburgh, the Earl of Arran had raised a large army, consisting mainly of pikemen with contingents of Highland archers. Arran also had large numbers of guns, but these were apparently not as mobile or as well-served as Somerset's. Arran had his artillery refurbished in August, after the siege of St Andrews Castle, with new gunstocks made from woods of "Aberdagy" and Inverleith. The Lord Treasurer's account describes this work as preparation "against the feild of Pynkie Cleuch."[18]

His cavalry consisted of only 2,000 lightly equipped riders under the Earl of Home, most of whom were potentially unreliable Borderers. His infantry and pikemen were commanded by the Earl of Angus, the Earl of Huntly and Arran himself.[19] According to Huntly, the Scottish army numbered 22,000 or 23,000 men, while an English source claimed that it comprised 36,000.[1]

Arran occupied the slopes on the west bank of the River Esk to bar Somerset's progress. The Firth of Forth was on his left flank, and a large bog protected his right. Some fortifications were constructed in which cannon and arquebuses were mounted. Some guns pointed out into the Forth to keep English warships at a distance.[8]

Prelude

Arran was at Monktonhall on 8 September where he made an act to protect the rights of the children and heirs of those men who would be killed fighting the English. James IV of Scotland had made a similar act at Twizell before Flodden in 1513.[20] On 9 September part of Somerset's army occupied Falside Hill (Falside Castle put up a slight resistance), three miles (five kilometres) east of Arran's main position. In an outdated chivalric gesture, the Earl of Home led 1,500 horsemen close to the English encampment and challenged an equal number of English cavalry to fight. With Somerset's reluctant approval, Lord Grey accepted the challenge and engaged the Scots with 1,000 heavily armoured men-at-arms and 500 lighter demi-lancers, led by Jacques Granado and others.[21] The Scottish horsemen were badly cut up and were pursued west for 3 mi (5 km). This action cost Arran most of his cavalry.[22] The Scots lost around 800 men in the skirmish. Lord Home was badly wounded, and his sons were taken prisoner.[23]

Later during the day, Somerset sent a detachment with guns to occupy the Inveresk Slopes, which overlooked the Scottish position. During the night, Somerset received two more anachronistic challenges from Arran. One request was for Somerset and Arran to settle the dispute by single combat;[6] another was for 20 champions from each side to decide the matter. Somerset rejected both proposals.[8]

Battle

On the morning of Saturday, 10 September, Somerset advanced his army, seeking to position his artillery at Inveresk.[8] In response Arran moved his army across the Esk by the "Roman bridge", and advanced rapidly to meet him. Arran may have seen movement in the English lines and assumed that the English were trying to retreat to their ships.[23] Arran knew himself to be outmatched in artillery and therefore tried to force close combat before the English artillery could be deployed.[8]

Arran's left wing came under fire from English ships offshore. Their advance meant that the guns at their former position could no longer protect them. They were thrown into disorder and pushed into Arran's own division in the centre.[8]

On the other flank, Somerset threw in his cavalry to delay the Scots' advance. The English cavalry was at a disadvantage, as they had left their horses' body armour at the camp. The Scottish pikemen drove them off, inflicting heavy casualties. Lord Grey himself was wounded by a pike thrust through his throat and into his mouth.[24] At one point, Scottish pikemen surrounded Sir Andrew Flammack, the bearer of the King's Standard. He was rescued by Sir Ralph Coppinger, and managed to hold onto the standard, despite its staff breaking.[8]

The Scottish army was by now stalled and under heavy fire on three sides, from the ships, land artillery, arquebusiers and archers, to which they had no reply. When they broke, the English cavalry rejoined the battle following a vanguard of 300 experienced soldiers under the command of Sir John Luttrell. Many of the retreating Scots were slaughtered or drowned as they tried to swim the fast-flowing Esk or cross the bogs.[25]

The English eye-witness William Patten described the slaughter inflicted on the Scots;

Soon after this notable strewing of their footmen's weapons, began a pitiful sight of the dead corpses lying dispersed abroad, some their legs off, some but houghed, and left lying half-dead, some thrust quite through the body, others the arms cut off, diverse their necks half asunder, many their heads cloven, of sundry the brains pasht out, some others again their heads quite off, with other many kinds of killing. After that and further in chase, all for the most part killed either in the head or in the neck, for our horsemen could not well reach the lower with their swords. And thus with blood and slaughter of the enemy, this chase was continued five miles [eight kilometres] in length westward from the place of their standing, which was in the fallow fields of Inveresk until Edinburgh Park and well nigh to the gates of the town itself and unto Leith, and in breadth nigh 4 miles [6 kilometres], from the Firth sands up toward Dalkeith southward. In all which space, the dead bodies lay as thick as a man may note cattle grazing in a full replenished pasture. The river ran all red with blood, so that in the same chase were counted, as well by some of our men that somewhat diligently did mark it as by some of them taken prisoners, that very much did lament it, to have been slain about 14 thousand. In all this compass of ground what with weapons, arms, hands, legs, heads, blood and dead bodies, their flight might have been easily tracked to every of their three refuges. And for the smallness of our number and the shortness of the time (which was scant five hours, from one to well nigh six) the mortality was so great, as it was thought, the like aforetime not to have been seen.[26]

The Imperial ambassador's accounts of the battle

The Imperial ambassador François van der Delft went to the court of King Edward VI at Oatlands Palace to hear the news of the battle from William Paget. Van der Delft wrote to the Queen Dowager, Mary of Hungary, with his version of the news on 19 September. He described the cavalry skirmish on the day before the battle. He had heard that on the day of the battle, when the English army encountered the Scottish formation, the Scots advance horsemen dismounted and crossed their lances, which they used like pikes standing in close formation. Van der Delft was told that the Earl of Warwick then attempted to attack the Scots from behind using smoking fires as a diversion. When they engaged the Scottish rearguard the Scots took flight, apparently following some who already had an understanding with the Protector Somerset. The rest of the Scots army then attempted to flee the field.[27]

Van der Delft wrote a shorter description for Prince Philip on 21 October. In this account he lays emphasis on the Scots attempting to change position. He said the Scots crossed the brook in order to occupy two hills which flanked both armies. The Scottish army, "without any need whatever were seized with panic and began to fly".[28] Another letter with derivative news of the battle was sent by John Hooper in Switzerland to the Reformer Henry Bullinger. Hooper mentions that Scots had to abandon their artillery due to the archers commanded by the Earl of Warwick, and when the Scots changed position the sun was in their eyes. He was told there were 15,000 Scottish casualties and 2,000 prisoners. There were 17,000 English in the field and 30,000 Scots. Hooper's letter is undated but he includes the false early report that Mary of Guise surrendered in person to Somerset after the battle.[29] These newsletters, though compiled and written by non-combatants days after the battle and far from the battlefield, are nevertheless important sources for the historian and for reconstruction of the events, to compare with Patten's narrative and archaeological evidence from the field.

Aftermath

Although they had suffered a resounding defeat, the Scottish government refused to come to terms. The infant Queen Mary was smuggled out of the country to France to be betrothed to the young Dauphin of France, Francis. Somerset occupied several Scottish strongholds and large parts of the Lowlands and Borders but, without peace, these garrisons became a useless drain on the Treasury.[30]

Analysis

Although the Scots blamed traitors for the defeat, it may be fairer to say that a Renaissance army defeated a medieval army. Henry VIII had taken steps towards creating standing naval and land forces which formed the nucleus of the fleet and army that gave Somerset the victory. However, the military historian Gervase Phillips has defended Scottish tactics, pointing out that Arran moved from his position by the Esk as a rational response to English manoeuvres by sea and land. In his 1877 account of the battle, Major Sadleir Stoney commented that "every amateur knows that changing front in presence of an enemy is a perilous operation".[31] Early commentators such as John Knox had focused on the move as the cause of the defeat and attributed the order to move to the influence of local landowners George Durie, Abbot of Dunfermline, and Hugh Rig of Carberry.[32] Marcus Merriman sees the initial Scottish field encampment as the most sophisticated ever erected in Scotland, let down by their cavalry numbers.[33]

Gervase Phillips maintains the defeat may be considered due to a crisis of morale after the English cavalry charge, and notes William Patten's praise of the Earl of Angus's pikemen.[34] Merriman regards Somerset's failure to press on and capture Edinburgh and Leith as a loss of "a magnificent opportunity" and "a massive blunder" which cost him the war.[35] In 1548, the Scottish Master of Artillery, Lord Methven, gave his opinion that the battle was lost due to growing support in Scotland for English policy, and the mis-order and great haste of the Scottish army on the day.[36]

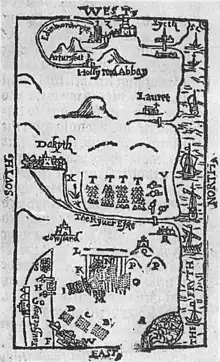

The naval bombardment was an important aspect of the battle. The English navy was commanded by Lord Clinton and comprised 34 warships with 26 support vessels.[37] William Patten mentions the Galley Subtle, captained by Richard Broke,[38] as one of the ships at the battle, and included it in one of his plans, depicted in the woodcut with its oars visible, close to Musselburgh.[39] The guns of the Galley and other ships in English fleet were recorded in an inventory. The Galley carried two brass demi-cannons, two brass Flanders demi-culverins, breech-loading iron double basses and single basses.[40]

Scottish artillery

Warned of the approach of the English army, the Scottish artillery was made ready at Edinburgh Castle. Extra gunners were recruited and 140 pioneers, i.e. workmen, were employed by Duncan Dundas to move the guns. On 2 September carts were hired to take the guns and the Scottish tents and pavilions towards Musselburgh. There were horses, and oxen were supplied by the Laird of Elphinstone. John Drummond of Milnab, master carpenter of the Scottish ordnance, led the wagon train. There was a newly painted banner, and ahead a boy played on the "swesche", a drum used to alert people.[41][42]

William Patten described the English officers of the Ordnance after the battle retrieving 30 of the Scottish guns, which were left lying in sundry places, on Sunday 11 September. They found one brass culverin, 3 brass sakers, 9 smaller brass pieces, and 17 other iron guns mounted on carriages.[43] Some of these guns appear in the English royal inventory of 1547–48, at the Tower of London where sixteen Scottish brass guns were recorded. They were a demi-cannon, 2 culverins, 3 sakers, 9 falconets, and a robinet.[44]

The fitted account of the English Treasurer General of the Army

Ralph Sadler was treasurer for Somerset's expedition in Scotland from 1 August to 20 November 1547. On 22 August, he informed the Earl of shrewsbury that ships were ready to sail to Aberlady with provisions.[45] The expense of the journey northwards cost £7468-12s–10d, and the return was £6065-14s–4d. Soldiers' wages were £26,299-7s–1d. For his own expenses, Sadler had £211-14s–8d with £258-14s–9d for his equipment and auditor's expenses. A number of special rewards were given to spies, Scottish guides, and others who gave good service, and to the captain of the Spanish mercenaries. The Scottish herald at the battlefield was given 100 shillings. When Sadler's account was audited in December 1547, Sadler was found to owe Edward VI £546-13s–11d which he duly returned.[46]

Today

The battle site is now in East Lothian. The battle took place most probably in the cultivated ground 1⁄2 mi (800 m) south-east of Inveresk Church, just to the south of the main East Coast railway line. There are two vantage points for viewing the ground. Fa'side Castle above the village of Wallyford was just behind the English position, and with the aid of binoculars, a visitor can get a good view of the battle area though the Scottish position is now obscured by buildings. The best impression of their position is obtained from the golf course west of the River Esk and just off the B6415 road. The Scottish centre occupied ground a few yards west of the clubhouse. The Inveresk eminence, an important tactical feature at the time of the battle, is now built over, but from it, a visitor can get down to the Esk and walk for some way along the bank. The walk gives a further idea of a part of the Scottish position, but the town of Musselburgh now completely covers the left of the line.[47] The battlefield was added to the Inventory of Historic Battlefields in Scotland in 2011.[48]

A stone commemorating the battle has been erected southwest of Wallyford village near the junction of Salters Road and the A1 road. The stone is carved with St. Andrew's Cross, the English rose and Scottish thistle and the name and date of the battle. It is situated on the north side of the driveway to the home that is in the northwest corner of the intersection. Co-ordinates: 55.9302992°N 3.0210942°W.

In September 2017 the Scottish Battlefields Trust staged the first major re-enactment of the battle in the grounds of Newhailes House. Such re-enactments are intended to continue on a triennial cycle.[49]

Casualties

Some of the injured soldiers were treated by Lockhart, a barber surgeon from Dunbar.[50] David H. Caldwell has written, "English estimates put the slaughter as high as 15,000 Scots killed and 2,000 taken but the Earl of Huntly's figure of 6,000 dead is probably nearer the truth."[3] Of the Scottish prisoners, few were nobles or gentlemen. It was claimed that most were dressed much the same as common soldiers and therefore were not recognised as being worth ransoming.[51] Caldwell says of the English casualties, "Officially it was given out that losses were only 200 though the rumour about the English court, fed by private letters from those in the army, indicated that 500 or 600 was more likely."[4]

William Patten names a number of high-ranking casualties. The Englishmen he names were horsemen forced onto Scottish pikes in a ploughed field to the east of the English position, after they had crossed a slough towards the Scottish position on Falside Brae.[52]

English

- Edward Shelley, subject of a lost portrait by Hans Eworth, fourth son of Sir William Shelley.

- Sir Walter Hawksworth, son of and heir of Thomas of Hawksworth, Yorkshire.

- The Lord Fitzwalter's brother

- Sir John Clere's son, a brother of the poet Thomas Clere (John Clere of Ormesby, Norfolk was killed in battle at Kirkwall on 21 August 1557).[53]

- Thomas Wodehouse, son of Sir Roger Wodehouse of Kimberley, Norfolk, and Madge Shelton

Scottish

- Malcolm, Lord Fleming

- Robert, Master of Graham, son and heir of William Graham, 2nd Earl of Montrose, killed in the naval bombardment

- Robert, Master of Erskine, son and heir of John Erskine, 5th Lord Erskine

- James, Master of Ogilvy, son and heir of James Ogilvy, 4th Lord Ogilvy of Airlie

- The Master of Avondale, son and heir of Andrew Stewart, 1st Lord Avondale

- The Master of Ruthven, son and heir of William Ruthven, 2nd Lord Ruthven

- John Stewart, Master of Buchan, son of John Stewart, 3rd Earl of Buchan

- The Master of Methven, son and heir of Henry Stewart, 1st Lord Methven

The names of a number of other Scottish casualties are known from legal records, cases falling under the act made at Monktonhall, or from Scottish chronicles,[54] and include;

- William Adamson of Craigcrook Castle[55]

- Andrew Agnew of Lochnaw Leswalt, Wigtownshire[56]

- Gilbert Agnew, Wigtownshire

- James Allardice, who fell under the royal banner[57]

- Andrew Anstruther of that Ilk

- James Blair, Middle Auchindraine

- Thomas Brodie of Brodie

- Alan Cathcart, 3rd Lord Cathcart

- William Cunninghame of Glengarnock

- Gabriel Cunyngham of Craigends

- John Crawfurd of Auchinames

- John Crawford of Giffordland[58]

- William Dishington of Ardross

- Robert Douglas of Lochleven

- Thomas Dumbreck of that Ilk[59]

- Archibald Dunbar of Baldoon, Kirkinner, Wigtownshire

- Alexander Dundas of Fingask

- Alexander Elphinstone, 2nd Lord Elphinstone

- Finla Mor, Findlay of Clan Farquharson, said to have carried the royal banner

- Henry Fithie, younger of Boysack

- David Forrester of Garden and Torwood[60]

- James Forrester of Corstorphine

- James Gordon of Lochinvar[61]

- John Gordon of Pitlurg

- David Hamilton of Broomhill, son-in-law of Robert, Lord Semple

- Cuthbert Hamilton of Canir, brother-in-law of David Hamilton of Broomhill

- George Henderson of Fordell, and his oldest son William[62]

- Kentigern "Mungo" Huntar of Hunterston[63]

- George Home of Wedderburn[64]

- James Innes of Cromy[65]

- Alexander Irvine, Master of Drum

- William Johnston, younger of Caskieben

- Thomas Kennedy, Vicar of Penpont, a son of Gilbert Kennedy, 2nd Earl of Cassilis

- Alexnder Kinninmonth[66]

- Alexander Lauder of Haltoun[67]

- James Learmonth of Dairsie and Balcomie

- John Leckie of Leckie, Dumbartonshire

- John, Master of Livingston, son of Alexander Livingston, 5th Lord Livingston

- Thomas MacCulloch of Plaids[68]

- John MacDowall of Garthland

- John MacDowall of Corswall, Kirkcolm, Wigtownshire

- Fergus McDouall of Freugh, Stoneykirk, Wigtownshire

- Richard Melville, father of Andrew Melville

- James Montfode of Montfode[69]

- Hugh Montgomerie, a son of the Earl of Eglinton

- Kentigern Muir of Rowallan[69]

- Robert Munro, 14th Baron of Foulis[68]

- Alexander Napier of Merchiston

- John Vans of Barnbarroch, Kirkinner, Wigtownshire[69]

Notes

- MacDougall, p. 73

- MacDougall, p. 68

- MacDougall, p. 86

- MacDougall, p. 87

- Mairi Robinson, The Concise Scots Dictionary (Edinburgh University Press, 1999), p. 101.

- Phillips, p. 193

- Marcus Merriman, The Rough Wooings: Mary Queen of Scots, 1542–1551 (Tuckwell: East Linton, 2000), pp. 7–8.

- Phillips, Gervase (12 June 2006). "Anglo-Scottish Wars: Battle of Pinkie Cleugh". HistoryNet. World History Group. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- Froude, James Anthony (1860). History of England from the Fall of Wolsey to the Death of Elizabeth, Vol. 5. London. p. 51. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Phillips, pp. 178–183

- Annie I. Cameron, Scottish Correspondence of Mary of Lorraine (SHS, Edinburgh, 1927), pp. 192–194.

- Stuart W. Pyhrr, Donald J. La Rocca, Dirk H. Breiding, The Armored Horse in Europe, 1480–1620 (New York, 2005), pp. 57–58: Nicolas Bellin's account, National Archives TNA E101/504/8, photograph by AALT.

- Phillips, p. 186

- Phillips, p. 183

- William Patten, The Late Expedition into Scotland (1548), in A. E. Pollard, Tudor Tracts (London, 1903), pp. 86–89

- Joseph Bain, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1898), p. 38 no. 78.

- Patrick Fraser Tytler, History of Scotland, vol. 3 (Edinburgh, 1879), p. 63: Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1898), p. 19 no. 42, Lennox & Wharton to Somerset, 16 September 1547.

- James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 9 (Edinburgh, 1911), p. 105.

- Phillips, pp. 181–182

- George Powell McNeill, Exchequer Rolls, 18 (Edinburgh, 1898), pp. lxvi-lxx: Patrick Fraser Tytler, History of Scotland, vol. 5 (Edinburgh, 1841), p. 57: Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1814), p. 278.

- A. F. Pollard, Tudor Tracts (London, 1903), p. 100

- Phillips, pp. 191–192

- "1547 Battle of Pinkie Cleugh". Tudor Times. p. 5. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Phillips, p. 196

- Phillips, pp. 197–199

- William Patten, The Expedicion into Scotlande (1548), in Fragments of Scottish History, ed. J. G. Dalyell, (Edinburgh, 1798).

- Calendar State Papers Spanish: 1547–1549, vol. 9 (London, 1912), pp. 150–153.

- Calendar State Papers Spanish: 1547–1549, vol. 9 (London, 1912), pp. 181–182.

- Hastings Robinson, Original Letters Relative to the Reformation (Parker Society: Cambridge, 1846), pp. 43–44 Letter XXIV.

- Phillips, p. 252

- F. Sadlier Stoney, Life and Times of Ralph Sadleir (Longman: London, 1877), p. 109.

- David Laing, Works of John Knox: History of the Reformation in Scotland, vol. 1 (Wodrow Society: Edinburgh, 1846), p. 211.

- Marcus Merriman, The Rough Wooings (Tuckwell: East Linton, 2000), p. 236.

- Gervase Phillips, 'Tactics', Scottish Historical Review (Oct. 1998), pp. 172–173.

- Marcus Merriman, The Rough Wooings (Tuckwell: East Linton, 2000), pp. 236–237.

- Annie I. Cameron, The Scottish Correspondence of Mary of Lorraine (Scottish History Society: Edinburgh, 1927) pp. 242–243, Methven to Mary of Guise, 3 June 1548.

- Albert F. Pollard, Tudor Tracts (London, 1903), p. 78

- John Bennell, 'The Oared Vessels', David Loades & Charles Knighton, The Anthony Roll of Henry VIII's Navy (Ashgate, 2000), p. 35.

- Albert F. Pollard, Tudor Tracts (London, 1903), pp. 115, 135: E. R. Adair, 'English Galleys in the Sixteenth Century', English Historical Review, 35:140 (October 1920), pp. 499–500

- David Starkey, Inventory of Henry VIII (London, 1998), p. 155 nos. 7950–7959.

- Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 9 (Edinburgh, 1911), pp. 112–120.

- "Swesch" see 'Swesche n. 1', Scottish Language Dictionaries, Edinburgh, DOST: Dictionary of the Scottish Language'

- William Patten, The Expedition into Scotland, 1547 (London, 1548), reprinted in, Tudor Tracts, (London, 1903), p. 136.

- David Starkey, The Inventory of Henry VIII, vol. 1 (Society of Antiquaries: London, 1998), p. 102, nos. 3707–3712.

- Joseph Stevenson, Selections from unpublished manuscripts illustrating the reign of Mary Queen of Scotland (Glasgow, 1837), p. 21.

- Arthur Clifford, Sadler State Papers, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1809), pp. 353–364.

- William Seymour, Battles in Britain: 1066–1547 vol. 1 (Sidgewick & Jackson, 1979), p. 208.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Battle of Pinkie (BTL15)". Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Event Scotland, 2017 re-enactment by the Scottish Battlefields Trust.

- James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 9 (Edinburgh, 1911), p. 160.

- Fraser, George Macdonald (1995). The Steel Bonnets. London: Harper Collins. p. 86. ISBN 0-00-272746-3.

- Patten, (1548), other English names not immediately recognisable.

- John Strype, Ecclesiastical Memorials, vol. 3 part 2, (1822), pp. 67–69, 86–87.

- E.g., Lindsay of Pitscottie, History of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1728), p. 195.

- The Scottish antiquary, or, Northern Notes & Queries, 8 (1890), p. 89.

- George Powell McNeill, Exchequer Rolls, 18 (Edinburgh, 1898), p. lxviii.

- HMC 5th Report: Barclay Allardice (London, 1876), p. 631: George Powell McNeill, Exchequer Rolls, 18 (Edinburgh, 1898), p. lxviii.

- James Paterson, History of the Counties of Ayr & Wigton Scotland: Cunninghame (Edinburgh, 1866), p. 345.

- Masson, David (1898). The Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, Vol. XIV. Edinburgh: H. M. Register House. p. 53. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- George Powell McNeill, Exchequer Rolls, 18 (Edinburgh, 1898), p. lxix.

- ?Stitchill Inventory: "deceissit vndir our baner in the feild of pynkecleuch"?

- Burke, Bernard (1862). A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland. Harrison. p. 682.

- James Paterson, History of the Counties of Ayr & Wigton Scotland: Cunninghame (Edinburgh, 1866), p. 345.

- HMC Report on the Manuscripts of Colonel David Milne Home of Wedderburn Castle (London, 1902), pp. 38–40

- Forbes, Duncan of Culloden, Ane Account of the Familie of Innes (Spalding Club, Aberdeen, 1864), pp. 28–29.

- George Powell McNeill, Exchequer Rolls, 18 (Edinburgh, 1898), p. lxviii.

- National Records of Scotland charter RH6/1534 dated 21st October 1551, grants a Sasine to William Lauder of Haltoun, "whose father Alexander Lauder of Haltoun had died in the Battle of Pinkie".

- Munro, R.W, ed. (1971). "Clan Munro Magazine" (12). Clan Munro Association: 40–44.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - George Powell McNeill, Exchequer Rolls, 18 (Edinburgh, 1898), p. lxx.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- William Patten, The Late Expedition into Scotland (1548), in A. E. Pollard, Tudor Tracts (London, 1903), pp. 53–157.

- Joseph Bain, Calendar of State Papers, Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1898).

- Teulet, Alexandre (1862). Relations politiques de la France et de l'Espagne avec l'Écosse au XVIe siècle, vol. 1. Paris: Société de l'Histoire de France.

- Teulet, A., ed., Relations politiques de la France et de l'Espagne avec l'Écosse au XVIe siècle, vol. 1 (1862) pp. 124–158, Latin account following William Patten.

- Arthur Clifford, Sadler State Papers, vol. 2 (Edinburgh (1809) pp. 353–364, the English army treasurer's account.

- David Constable, Jean de Berteville's Récit de l'expédition en Ecosse l'an 1546 et de la battayle de Muscleburgh (Bannatyne Club: Edinburgh, 1825), a French eyewitness fighting on English side.

- Philip de Malpas Grey Egerton, A commentary of the services and charges of William Lord Grey of Wilton, by his son Arthur Grey, Camden Society (1847).

Secondary sources

- Macdougall, Norman (1991). Scotland and War, AD 79–1918. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0-85976-248-3..

- David H. Caldwell, 'The Battle of Pinkie,' in Norman Macdougall, Scotland and War, AD 79–1918 (Edinburgh, 1991), pp. 61–94.

- Merriman, Marcus (2000). The Rough Wooings. Tuckwell. ISBN 1-86232-090-X.

- Phillips, Gervase (1999). The Anglo-Scots Wars 1513–1550. Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-746-7.

- Phillips, Gervase, 'In the Shadow of Flodden: Tactics, Technology and Scottish Military Effectiveness, 1513–1550', Scottish Historical Review, vol.b77, no. 204 part 2, EUP (Oct. 1998), pp. 162–182.

- Phillips, Gervase, 'Anglo-Scottish Wars: Battle of Pinkie Cleugh', Military History, August (1997).

- F. Sadlier Stoney, Life and Times of Ralph Sadleir (Longman: London. 1877) pp. 107–114.

- Warner, Philip (1996). Famous Scottish Battles. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-487-3.

- "News Item: Magnificent Pinkie Cleugh commemoration and re-enactments delight thousands". www.battleofprestonpans1745.org. Retrieved 12 April 2018..

- Alex Hodgson, an East Lothian born folk singer/songwriter pays tribute to the battle of Pinkie Cleugh through the song Doon Pinkie Cleugh on his second album 'The Brig Tae Nae Where', published on Scottish folk record label Greentrax Recordings.

External links

- Battle of Pinkie entry in the Scottish Government Inventory of Historic Battlefields.

- Guide to walking the Battlefield, Musselburgh Museums.

- Battle of Pinkie, exhibition in 2013, Musselburgh Museum.

- Battle of Pinkie, information from the John Gray Centre, Haddington.

- Battle of Pinkie, summary of assessment and new mapping from Geddes Consulting, AOC Archaeology, David H. Caldwell.

- Summary of 2010 BBC Radio 4 program on early battle drawing, Bodleian MS. Eng. Misc. C.13 (R)/(30492)

- Battle of Prestonpans