Battle of Pirano

The Battle of Pirano (also known as the Battle of Grado) on 22 February 1812 was a minor naval action of the Adriatic campaign of the Napoleonic Wars fought between a British and a French ship of the line in the vicinity of the towns of Piran and Grado in Adriatic Sea. The French Rivoli, named for Napoleon's victory 15 years earlier, had been recently completed at Venice. The French naval authorities intended her to bolster French forces in the Adriatic, following a succession of defeats in the preceding year.

| Battle of Pirano | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Adriatic Campaign of the Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

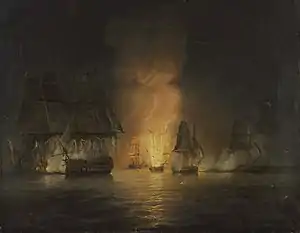

HMS Victorious Taking the Rivoli, 22 February 1812, Thomas Luny | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 ship of the line 1 brig-sloop |

1 ship of the line 3 brigs 2 gunboats | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 126 killed and wounded |

400 killed and wounded 1 ship of the line captured 1 brig destroyed | ||||||

To prevent this ship challenging British dominance in the theatre, the Royal Navy ordered a ship of the line from the Mediterranean fleet to intercept and capture Rivoli on her maiden voyage. Captain John Talbot of HMS Victorious arrived off Venice in mid-February and blockaded the port. When Rivoli attempted to escape under cover of fog, Talbot chased her and forced her to surrender in a five-hour battle, Rivoli losing over half her crew wounded or dead.

Background

The Treaty of Tilsit in 1807 had resulted in a Russian withdrawal from the Adriatic and the French takeover of the strategic island fortress of Corfu. The Treaty of Schönbrunn with the Austrian Empire in 1809 had further solidified French influence in the area by formalising their control of the Illyrian Provinces on the Eastern shore.[1] To protect these gains, the French and Italian governments had instigated a shipbuilding program in Venice and other Italian ports in an effort to rebuild their Mediterranean fleet and challenge British hegemony. These efforts were hampered by the poverty of the Italian government and the difficulty that the French Navy had in manning and equipping their ships.[2] As a result, the first ship of the line built in the Adriatic under this program was not launched until 1810 and not completed until early 1812.[2]

By the time this ship, Rivoli, was launched, the Royal Navy had achieved dominance over the French in the Adriatic Sea.[3] Not only had the regional commander Bernard Dubourdieu been killed and his squadron destroyed at the Battle of Lissa in March 1811, but French efforts to supply their scattered garrisons were proving increasingly risky.[3] This was demonstrated by the destruction of a well-armed convoy from Corfu to Trieste at the action of 29 November 1811.[4] Rivoli's launch was therefore seen by the French Navy as an opportunity to reverse these defeats, as the new ship of the line outgunned the British frigates that operated within the Adriatic and would be able to operate in the Adriatic without the threat of attack by the frigate squadron based on Lissa.[5]

The Royal Navy was aware of the threat that Rivoli posed to their hegemony and were warned in advance by spies in Venice of the progress of the ship’s construction.[5] As Rivoli neared completion, HMS Victorious was dispatched from the Mediterranean Fleet to intercept her should she leave port. Victorious was commanded by John Talbot, a successful and popular officer who had distinguished himself with the capture of the French frigate Ville de Milan in 1805 and his service in the Dardanelles Operation of 1807.[6] Talbot was accompanied by the 18-gun brig HMS Weazel under Commander John William Andrew.[7]

Battle

.jpg.webp)

Rivoli departed Venice on 21 February 1812 under the command of Commodore Jean-Baptiste Barré, accompanied by five smaller escort ships, the 16-gun brigs Mercurio and Eridano, of the navy of the Kingdom of Italy, the eight-gun brig Mamelouck and two small gunboats, strung out in an improvised line of battle. Barré hoped to make use of a heavy sea fog that had descended, to break out from Venice and elude pursuit. Victorious had held off from the land during the fog and by the time Talbot was able to observe Venice harbour at 14:30, his opponent had escaped. Searching for Barré, who was sailing to Pula, Talbot spotted one of the French brigs at 15:00 and gave chase.[7]

The French head-start had enabled Rivoli to gain a substantial distance on the British ship, and so it was not until 02:30 on 22 February that Talbot was able to close with his quarry and its escort.[7] Not wishing to be held up by the escort ships protecting Rivoli, Talbot ordered Weasel ahead to engage them while Victorious fought Barré's flagship directly. At 04:15, Weasel overhauled the rearmost French brig Mercure and opened fire from close range, Mercure replying in kind.[7] Iéna also engaged Weasel but the greater distance between these ships allowed Commander Andrew to focus his attack on Mercure, which fought hard for twenty minutes before being destroyed in a catastrophic explosion, probably caused by a fire in the magazine.[5] Weasel immediately launched her boats to rescue any survivors, but only three were saved.[5]

Following the explosion aboard Mercure, Iéna and the other French brigs scattered, briefly pursued by Weasel, who chased Iéna and Mamelouck but was unable to bring them to a decisive action. The loss of the French escorts allowed Victorious to close with Rivoli unopposed, and at 04:30 the two large ships began a close-range artillery duel. This combat continued unabated for the next three and a half hours, both ships being severely damaged and suffering heavy casualties.[5] Captain Talbot was struck on the head by a flying splinter and had to quit the deck, temporarily blinded, with command passing to Lieutenant Thomas Peake. To assist in subduing Rivoli, Peake recalled Weasel to block the French ship's attempts to escape, while Commander Andrew sailed his ship in front of Rivoli and repeatedly raked her.[8]

Surrender and aftermath

.jpg.webp)

At 08:45 Rivoli, which had been struggling to reach the harbour of Trieste, lost her mizzenmast under fire from both Victorious and Weasel. Nearly at the same moment, two of her 36-pounder long guns exploded, killing or wounding 60 men, greatly disorganising and demoralising the others, and forcing Barré to transfer gunners from the upper gun deck to man his lower battery.[9] Fifteen minutes later, with his ship unmanageable and battered, Commodore Barré surrendered.[8] Rivoli had suffered over 400 killed and wounded from her crew of over 800, who had only assembled for the first time a few days before and had never sailed their ship in open water.[10] Losses aboard Victorious were also heavy, with one officer and 25 sailors and marines killed and six officers (including Captain Talbot) and 93 men wounded.[11]

French losses on Mercure, although unknown exactly, were severe, only three sailors surviving. Weasel, despite being engaged with three different French ships for a considerable time, had not one man killed or wounded during the entire engagement. Rivoli's scattered escorts were not pursued, British efforts being directed instead at bringing the shattered Rivoli back to port as a prize.[12] As a result, the remaining French ships were able to make their way to friendly ports unopposed. Rivoli was a new and well-built ship and, following immediate repairs at Port St. George, she and Victorious traveled together to Britain. There they were both repaired, Victorious returning to the fleet under Talbot for service against the United States Navy during the War of 1812, and Rivoli commissioned as HMS Rivoli for service in home waters.[6]

The crews of Victorious and Weasel were well rewarded with both promotions and prize money, the junior officers either promoted or advanced and Commander Andrew of Weasel made a post captain.[12] Captain Talbot was rewarded at the end of the war, becoming Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in recognition of his success.[6] Nearly four decades later the battle was among the actions recognised by a clasp attached to the Naval General Service Medal, awarded upon application to all British participants still living in 1847.[13] This was the last significant ship-to-ship action in the Adriatic, and its conclusion allowed British raiders to strike against coastal convoys and shore facilities unopposed, seizing isolated islands and garrisons with the aid of an increasingly nationalistic Illyrian population.[14]

See also

Notes

- Gardiner, p. 153

- James, p. 44

- Gardiner, p. 174

- Gardiner, p. 178

- Gardiner, p. 179

- Talbot, Sir John, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, J. K. Laughton, Retrieved 28 May 2008

- James, p. 64

- James, p. 65

- Troude, op. cit., p. 157

- British accounts claim there were 862 sailors aboard Rivoli, French 810. (James p.64)

- James, p. 66

- James, p. 67

- "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 244.

- Gardiner, p. 180

References

- Gardiner, Robert (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 6, 1811–1827. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-910-7.

- Troude, Onésime-Joachim (1867). Batailles navales de la France. Vol. 4. Challamel ainé. pp. 152–153.