Battle of Pydna

The Battle of Pydna took place in 168 BC between Rome and Macedon during the Third Macedonian War. The battle saw the further ascendancy of Rome in the Hellenistic world and the end of the Antigonid line of kings, whose power traced back to Alexander the Great.[2] The battle is also considered to be a victory of the Roman legion's manipular system's flexibility over the Macedonian phalanx's rigidity.[3]

| Battle of Pydna | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Macedonian War | |||||||

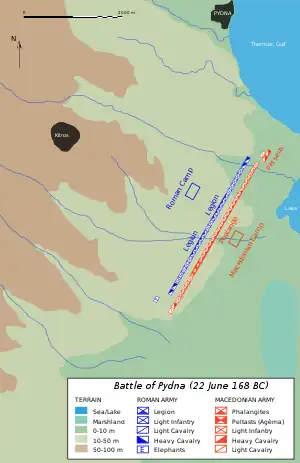

Dispositions prior to the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Lucius Aemilius Paullus P. Cornelius Scipio Nasica | Perseus (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

38,600 men ● 2,600 cavalry 22 war elephants |

43,000 men ● 4,000 cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Unknown [1] numerous wounded |

31,000 •20,000 killed •11,000 captured | ||||||

Prelude

The Third Macedonian War started in 171 BC, after a number of acts on the part of King Perseus of Macedon incited Rome to declare war. At first, the Romans won a number of small victories, largely due to Perseus' refusal to consolidate his armies. By the end of the year, the tide changed dramatically and Perseus had gained a success at the Battle of Callinicus and regained most of his losses, including the important religious city of Dion. Perseus then established himself in an unassailable position on the river Elpeus, in northeastern Greece.

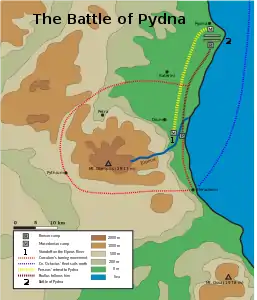

The next year, command of the Roman expeditionary force passed to Lucius Aemilius Paullus, an experienced soldier who was one of the consuls for the year. To force Perseus from his position, Paullus sent a small force (8,200 foot and 120 horse) under the command of Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica Corculum to the coast, a feint to convince Perseus that he was attempting a riverborne flanking maneuver. Instead, that night Scipio took his force south and over the mountains to the west of the Roman and Macedonian armies. They moved as far as Pythion, then swung northeast to attack the Macedonians from the rear.

A Roman deserter, however, made his way to the Macedonian camp and Perseus sent a force of 12,000 under the command of Milo to block the approach road. The encounter that followed sent Milo and his men back in disarray towards the main Macedonian army. After this, Perseus moved his army northwards and took up a position near Katerini, a village south of Pydna. It was a fairly level plain and was very well suited to the phalanx.

Paullus then had Scipio rejoin the main force, while Perseus deployed his forces for what appeared to be an attack from the south by Scipio. The Roman armies were actually to the west, and when they advanced, they found Perseus fully deployed. Instead of joining battle with troops tired from the march, they encamped to the west in the foothills of Mount Olocrus. The night before the battle there was a lunar eclipse, which was perceived by the Macedonians as an ill omen; according to Plutarch, they interpreted it as a sign of their king's demise. Meanwhile, Paullus is said to have understood that eclipses occurred at regular intervals but still believed it was necessary to perform sacrifices and wait for "favourable omens."[4]

The fighting began the afternoon of the next day, June 22. The exact cause of the start of the battle differs; one story is that Paullus waited until late enough in the day for the sun not to be in the eyes of his troops, and then sent an unbridled horse forward to bring about alarm. More likely it was the result of some Roman foragers getting a little too close and being attacked by some Thracians in Perseus' army.[5]

Battle

The Romans had at least 28,600 men, up to 37,000, of which 22,000 to 34,000 were infantry: Romans, Italians, and allies from Greece, Numidia, and Liguria,[6] as well as possibly Hispania.[7] The Macedonians had 43,000 soldiers at the start of the war, of which more than 20,000 were phalangites.[8] The cavalry forces were roughly equal, up to 4,000 Macedonians and Thracians against some 3,400 Romans and allies.[9] By the time of the battle, the Macedonian army numbered closer to 30,000 men.[10] For example, prior to the battle Perseus dispatched 8,000 of his Macedonians to guard against the Roman fleet threatening his rear: 2,000 peltasts, 5,000 phalangites, and 1,000 cavalry.[11] The two armies were drawn up in their usual fashion. The Romans had placed the two legions in the middle, with the allied Latin, Italian, and Greek infantry on their flanks. The cavalry was placed on the wings, with the Roman right being supplemented by 22 elephants. The phalanx took up the center of the Macedonian line, with the elite 3,000-strong Guard formed to the left of the phalanx. Lighter peltasts, mercenaries, and Thracian infantry guarded the two flanks of the phalanx, while the Macedonian cavalry was also most probably arrayed on both flanks. The stronger contingent was on the Macedonian right, where Perseus commanded the heavy cavalry (including his elite Sacred Squadron), and the Thracian Odrysian cavalry were deployed. However, other sources state that the cavalry did not participate in the fight, as there was a strike against Perseus by the nobles.

The two centers engaged at about 3pm, with the Macedonians advancing on the Romans a short distance from the Roman camp. Paullus claimed later that the sight of the phalanx filled him with alarm and amazement. The Romans allies tried to beat down the enemy pikes or hack off their points, but with little success. Roman allies' officers began to despair. One 'rent his garments' in impotent fury. Another seized his unit's standard and threw it among the enemy. His men made a desperate charge to recapture it, but were beaten back despite inflicting some casualties. Unable to get under the thick bristle of pikes, the Romans used a planned retreat over the rough ground.

But as the phalanx pushed forward, the ground became more uneven as it moved into the foothills, and the line lost its cohesion, being forced over the rough terrain. Paullus now ordered the legions into the gaps, attacking the phalangites on their exposed flanks. At close quarters the longer Roman sword and heavier shield easily prevailed over the Macedonian Kopis and lighter shields of the Macedonians. They were soon joined by the Roman right, which had succeeded in routing the Macedonian left.

Seeing the tide of battle turn, Perseus fled with the cavalry on the Macedonian right. According to Plutarch, Perseus' cavalry had yet to engage, and both the king and his cavalry were accused of cowardice by the surviving infantry. Poseidonius claimed that the king was injured by enemy missiles and was brought to the city of Pydna at the start of the battle. However, the 3,000 strong guard fought to the death, nearly 11,000 Macedonians were captured, and Livy reported that his various sources claimed up to 20,000 Macedonian dead.[12] The battle lasted about an hour, but the bloody pursuit lasted until nightfall. Other reports state that due to confusion of tactical error from the king, a corps of 10,000 Macedonians were cut off and did not participate in the engagement.[13]

There were several heroes among the Romans. Paullus's son Scipio Aemilianus was thought to be lost for a while, but he and some friends had been pursuing the retreating Macedonians. The son of Cato the Elder, Marcus Porcius Cato Licinianus distinguished himself in the battle by his personal prowess in a combat in which he first lost and finally recovered his sword.

The battle is often considered to be a victory of the Roman legion's flexibility over the phalanx's inflexibility. Nevertheless, modern conclusions are that the loss was actually due to a failure of command on the part of Perseus, as well as the peculiar stance of the Companion cavalry, who did not engage the enemy.[14] From the case of the 3,000 Agema peltasts, who maintained cohesion far longer than the regular phalanx, it may be concluded that the training levels of the troops involved played an important role in determining both the frontal strength of the pike phalanx and the success of infantry trying to break through the pike wall.

Aftermath

This was not the final conflict between the two rivals, but it broke the back of Macedonian power. The Battle of Pydna and its political aftermath mark the effective end of Macedonian independence, although formal annexation was still some years away.

The political consequences of the lost battle were severe. Perseus later surrendered to Paullus, and was paraded in triumph in Rome in chains. He was then imprisoned. The Senate's settlement included the deportation to Italy of many of the king's friends[15] and the imprisonment (later house arrest) of Perseus at Alba Fucens.[16]

The Macedonian kingdom was dissolved, and its government was replaced with four republics which were heavily restricted from intercourse or trade with one another. In time, these were also dissolved, and Macedonia became a Roman province. In 167 BC, Paullus received orders to attack Epirus, resulting in the enslavement of 150,000 Epirotes and the sacking of 70 cities.[17] This took place because the Molossians, one tribe of the Epirote League, had sent aid to Perseus, but all the Epirotes suffered alike in the Roman attack.

The victory was celebrated in Athens, where an inscribed decree passed by the Council and People in 168 BC honours Calliphanes, an Athenian citizen who had been present with the Roman and Attalid armies at Pydna, for bringing news of the victory to Athens.[18]

Summary

- The engagements on the river bed which were initiated by Aemilius to divert the prying eyes of Perseus away from a turning movement.

- "The large turning movement executed by Nasica to circumvent the enemy's position."[19]

- Paullus aimed to fight in the afternoon when the sun would be facing the enemy and not the Romans.

- The ancient ploy, executed by Salvius, of hurling the standard into the enemy was meant to arouse the ferocity of his men. In this instance, it was to no avail.

- Perseus' heavy cavalry failed to engage when the Romans began retreating over rough ground.

- Gaps developed in the phalanx when it moved onto uneven terrain, and the consul's initiative and response was immediate.

- The development of a large gap in the line between the Macedonian phalanx and the mercenaries. This gap was penetrated by the Romans and they attacked the flank of the phalanx.

- Approximately 1/4 of the Macedonian army inexplicably did not participate in the battle.

- The elephants were ineffective against the mercenaries.[20]

See also

- Monument of Aemilius Paullus, commemorates the Roman victory in the Battle of Pydna

References

- "Battle of Pydna".

- Paul K. Davis, 100 Decisive Battles from Ancient Times to the Present: The World’s Major Battles and How They Shaped History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 51.

- "Battle of Pydna".

- Plutarch, "Roman Lives." pp. 56–57. Robin Waterfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-19-953738-9

- Livy scribes that the start of the battle erupted due an escaped mule that ran across the river, which was then captured by Thracians who were killed by pursuing Romans, this angered the Thracian guard on the bank what started a skirmish leading to the battle commencing.

- Livy 42.35, 42.52, 44.21

- Fernando Quesada Sanz, Not so different: individual fighting techniques and small unit tactics of Roman and Iberian armies within the framework of warfare in the Hellenistic Age. Pallas 70 (2006), pp. 245–263.

- Livy 42.51

- Livy 42.52

- Livy 44.20

- Livy 44.32

- Livy 44.42

- who?

- who?

- Livy 45.32

- Livy 45.42

- Livy 45.34

- Lambert, Stephen; Schuddeboom, Feyo. "IG II3 1 1334: Honours for the soldier Kalliphanes, messenger of the Roman victory at Pydna". Attic Inscriptions Online. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- Montagu, John Drogo (2006). Greek & Roman Warfare: Battles, Tactics, and Trickery. London: Greenhill Books. p. 227.

- Montagu, John Drogo (2006). Greek & Roman Warfare: Battles, Tactics, and Trickery. London: Greenhill Books. p. 227.

Bibliography

- Angelides, Alekos, A History of Macedonia

- Paul K. Davis, 100 Decisive Battles from Ancient Times to the Present: The World’s Major Battles and How They Shaped History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 1576070751 OCLC 42579288

- J.F.C. Fuller. A Military History of the Western World: From The Earliest Times To The Battle of Lepanto. Da Capo Press, Inc., New York. ISBN 0306803046 (v. 1). pp. 151–69.

- Pydna

- Scullard, H.H., A History of the Roman World from 753 to 146 BC London: Methuen, 1935. Reprinted 1980. ISBN 0416714803 OCLC 6969612

- The Third Macedonian War, The Battle of Pydna

- Johstono, P. and M. Taylor. "Reconstructing the Battle of Pydna." Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 62.2 (2022), 44–76.