Battle of Taku Forts (1859)

The Second Battle of Taku Forts (Chinese: 第二次大沽口之戰) was a failed Anglo-French attempt to seize the Taku Forts along the Hai River in Tianjin, China, in June 1859 during the Second Opium War. A chartered American steamship arrived on scene and assisted the French and British in their attempted suppression of the forts.

| Second Battle of Taku Forts | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Opium War | |||||||

The Taku Forts | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Britain: 1,160 (on land)[1] 11 gunboats 4 steam ships[1] |

4,000[2] 60 guns[2] 6 forts[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Britain: 3 gunboats sunk 3 gunboats grounded[1] 81 killed[3] 345 wounded[3] France: 12 killed 23 wounded United States: 1 killed 1 wounded 1 launch damaged | 32 killed or wounded[2] | ||||||

Background

After the First Battle of Taku Forts in 1858, the Xianfeng Emperor appointed the Mongol general Sengge Rinchen to take charge of coastal defense. Sengge Rinchen hailed from a rich lineage - the 26th generation descendant of Qasar, a brother of Genghis Khan. He took to this task with ardor, repairing and improving the coastal defenses in preparation for the British arrival.[4]

A second, stronger boom was constructed across the river to further restrict the movement of British ships. This second boom was made of full-sized tree trunks, connected with heavy chains. Two rows of ditches were dug in front of the forts' walls, filled with water and mud, and an abatis of iron spikes placed immediately behind it.[5] Finally, Sengge Rinchen ensured the Chinese defenders and their cannon were trained and equipped to resist the coming British ships and their landing parties.

Battle

On the morning of June 25, 1859, the British could see that the Chinese fort's defenses were somewhat improved from the previous year. However, there did not appear to be many defenders, they did not see the flags and gongs that might indicating an impending battle, and the portholes for the guns were covered in matting. Local informants indicated to them that the fort was manned only by a skeleton crew. Even when, as an experiment, they cut through the first boom, they encountered no resistance.

The British then attempted to ram the second boom with their admiral's ship, Plover, as they had successfully done the year before. This time, though, the heavy boom stopped the British gunship cold.[6] As the advance of the British fleet stalled, the matting was removed from the portholes, revealing the fort's defenders, and the fort's guns opened fire. “On the Admiral’s reaching the first barrier the forts suddenly swarmed with men, and a terrible fire from very heavy guns was opened... from all the forts.” - American Commodore Josiah Tattnall

The first salvo decapitated the Plover's bow gunner. Under heavy fire from the fort, her hull eventually burst, sinking the ship into the mud and killing all of the crew but one. The rest of the British fleet was similarly devastated—two ships were forced to run aground, and two others were sunk in the river by the fort's cannon. Others attempted to retreat as the fort's smaller guns picked off their officers and men from the shore.

That evening, when the rate of fire from the Chinese guns finally slackened, the British determined to bring up their reserve forces and launch landing parties for a direct assault. The strength of the Hai River's flow required a ship to tow the infantry boats, as otherwise the soldiers would exhaust themselves with rowing before reaching land. Commodore Josiah Tattnall III, commanding the chartered steamship Toey-Wan which was also attempting to navigate past the forts, decided to assist and towed several loaded boats upstream into the battle. This act of military assistance was arguably a violation of the official neutrality between the United States and China.[7]

The landing had been delayed for so long that British landing parties were forced to come ashore at low tide, hundreds of meters from the Chinese fort's walls. There, the British marines slipped and stuck in the muddy riverbanks, where they were shot to pieces by Chinese gunners. Those British who were able to make it to the trenches found them filled with a mixture of mud and water too thin to walk on and too thick to swim through, soaking their ammunition and further exposing them to fire. As night fell, those who were finally able to reach the fort's walls found themselves trapped under the fort's walls, as the defenders dangled sizzling fireworks on long poles over the edge of the wall to illuminate them to the archers above.

One boat managed to gather a handful of the wounded, but it was struck by a well-aimed cannon shot. It broke in half and sank, drowning all on board.[7]

By sunrise the next morning, over four hundred British were dead or wounded, including twenty-nine officers. Chinese casualties were reported to be minimal.

Aftermath

An American interpreter and missionary named Samuel Wells Williams wrote that this was possibly the worst defeat the British had suffered since the 1842 retreat from Kabul. One of the battle's survivors declared he would rather relive the 1854 Battle of Balaclava, with its disastrous charge of the Light Brigade, three times rather than experience what they'd just suffered at the hands of Sengge Rinchen at the Taku forts.[7]

Sengge Rinchen rejoiced in his well-earned victory, writing to the Emperor that while the British and their allies might return with more ships, with one or two more victories "the pride and vainglory of the barbarians, already under severe trial, will immediately disappear."[8]

The Emperor was cautious, stating that the foreigners "may harbor secret designs and hide themselves around nearby islands, waiting for the arrival of more soldiers and ships for a surprise attack in the night or in a storm."[8]

The battle not only was a loss for the British, it caused them to have to assemble another massive fleet of 18,000 troops which fought in the Third Battle of Taku Forts. The battle also delayed the next British attack for 13 months, which extended the war for another year.

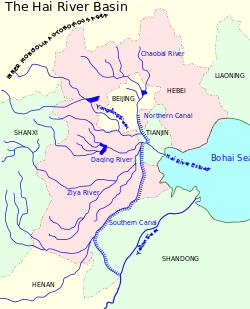

The Pei-ho's river basin, known as the Hai River today.

The Pei-ho's river basin, known as the Hai River today. Map of the attack on 25 June

Map of the attack on 25 June A gun battery of the Taku Forts

A gun battery of the Taku Forts

References

- Bartlett, Beatrice S. Monarchs and Ministers: The Grand Council in Mid-Ch'ing China, 1723–1820. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1991.

- Ebrey, Patricia. Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993.

- Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies." Journal of Asian Studies 59 (2000): 603-46.

- Faure, David. Emperor and Ancestor: State and Lineage in South China. 2007.

- Platt, Stephen (2012). Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War.

Notes

- Janin, Hunt (1999). The India-China Opium Trade in the Nineteenth Century. McFarland. p. 126–127. ISBN 0-7864-0715-8.

- "The Second Battle of the Taku Forts". unitedcn.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2010-09-15.

- Raugh, Harold E. (2004). The Victorians at War, 1815-1914: An Encyclopedia of British Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 100. ISBN 1-57607-925-2.

- Zhang, Senggelinqin chuanqi, p. 97

- Platt, Stephen (2012). Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War

- George Battye Fisher, Personal Narrative of Three Years' Service in China, pp. 190-193

- Williams, Frederick (1889). The Life and Letters of Samuel Wells Williams. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 302–312.

- T.F. Tsiang, "China after the Victory of Taku, June 25, 1859," "American Historical Review 35, no. 1 (October 1929)