Battle of Tournay (1794)

The Battle of Tournay or Battle of Tournai or Battle of Pont-à-Chin (22 May 1794) saw Republican French forces led by Jean-Charles Pichegru attack Coalition forces under Emperor Francis II and Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. After a bitter all-day struggle, Coalition troops recaptured a few key positions including Pont-à-Chin, forcing the French to retreat. The Coalition allies included soldiers from Austria, Great Britain, Hanover, and Hesse-Darmstadt. The Flanders Campaign battle was fought near Tournai in modern Belgium on the Schelde River, located about 80 km (50 mi) southwest of Brussels.

| Battle of Tournay (1794) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Flanders campaign in the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

Austrian command at the Battle of Tournay | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 28,000–50,000 | 45,000–62,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,000–4,000 | 6,000, 7 cannons | ||||||

Location within Europe | |||||||

In late April 1794, French forces seized both Courtrai and Menin. On 10–12 May in the Battle of Courtrai and on 17–18 May in the Battle of Tourcoing, the Coalition army failed to dislodge French forces holding these two cities. In a bid to drive the Allies from Tournai, Pichegru launched a frontal attack on their positions west of the city. Though the French were repulsed, the severe fighting in April and May 1794 convinced many Coalition leaders that defending the Austrian Netherlands was a lost cause.

Background

Armies

For 1794, Lazare Carnot of the Committee of Public Safety authored a strategy that directed the French armies to strike at both flanks of the Coalition army defending the Austrian Netherlands. The French left wing would seize Ypres, Ghent, and Brussels, while the right wing captured Namur and Liège in order to disrupt the Austrian line of communications to Luxembourg City. Meanwhile, the French center would stay on the defensive the between Bouchain and Maubeuge.[1] Pichegru, the Army of the North's new commander arrived at Guise on 8 February 1794.[2] In March 1794, the Army of the North counted 194,930 men, including 126,035 soldiers in the field army. Pichegru was also given authority over the subordinate Army of the Ardennes which had 32,773 men; the combined armies totaled 227,703 troops.[3] On 13 April 1794, Pichegru came to Lille to organize the forces of his left wing. These consisted of Pierre Antoine Michaud's 13,943-man division at Dunkirk, Jean Victor Marie Moreau's 15,968-strong division at Cassel, Joseph Souham's 31,865-man division at Lille, and Pierre-Jacques Osten's 7,822-strong brigade at Pont-à-Marcq.[4]

At the start of April 1794, the Coalition field army of Prince Coburg occupied the following positions. The right wing consisted of 24,000 Austrians, Hanoverians, and Hessians under Count François of Clerfayt with headquarters at Tournai. On Clerfayt's left, Ludwig von Wurmb's 5,000 soldiers were holding Denain. The 22,000 troops of the right-center were led by the Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany at Saint-Amand-les-Eaux. Prince Coburg's headquarters and the 43,000 troops of the center were at Valenciennes. William V, Prince of Orange commanded 19,000 Dutch of the left-center at Bavay. Franz Wenzel, Graf von Kaunitz-Rietberg commanded 27,000 Austrian and Dutch troops of the left wing at Bettignies watching French-held Maubeuge. Johann Peter Beaulieu's 15,000 Austrians guarded the extreme left from Namur to Trier.[5] On 14 April, Emperor Francis arrived at Valenciennes and Coburg urged that the fortress of Landrecies be attacked first.[6]

Operations

The Siege of Landrecies began an 21 April and ended on 30 April with a French surrender.[7] On 24 April, Pichegru launched an offensive by the left wing of the Army of the North. Michaud's division advanced toward both Nieuport on the coast and Ypres. Moreau's division swept past Ypres and surrounded Menin. Souham's division, accompanied by Pichegru, moved through Mouscron to seize Courtrai. In reaction, Clerfayt rapidly marched 10,000 troops to Mouscron on 28 April.[8] The next day, Souham concentrated 24,000 men against Clerfayt and defeated him in the Battle of Mouscron, capturing 3,000 Coalition troops and 33 guns. The Coalition garrison successfully broke out of Menin, leaving that place and Courtrai in French hands.[9]

Twice the Coalition allies tried to recapture the two cities. On 5 May, the Duke of York with 18,000 troops arrived at Tournai, joining Clerfayt with 19,000 and Johann von Wallmoden-Gimborn with 4,000–6,000 Germans. Meanwhile, Pichegru had added Jacques Philippe Bonnaud's 20,000-man division to the 40,000–50,000 French soldiers already in the area. On 10 May in the Battle of Courtrai, 23,000 French troops under Bonnaud and Osten attacked York but were beaten mostly by British cavalry. On the same day, Clerfayt attacked Courtrai from the north but failed to capture it.[10] On 11 May, Souham overwhelmed Clerfayt and forced him to retreat to Tielt. Realizing the numerical odds against him, York called for reinforcements.[11]

In the Battle of Tourcoing on 17–18 May, the Coalition army under Coburg concentrated 74,000 soldiers in a major effort to crush the 82,000-strong French forces led temporarily by Souham. The result was a French victory due to a serious breakdown in Allied cooperation and staff work.[12] Coburg and his chief-of-staff Karl Mack von Leiberich planned to catch the French at Courtrai and Menin between five converging columns from the south and Clerfayt's column from the north.[13] Souham and his lieutenants Moreau, Étienne Macdonald, and Jean Reynier devised a counterstroke whereby the divisions of Souham and Bonnaud attacked the two most advanced Coalition columns while Moreau held off Clerfayt.[14] On 18 May, the French crushed the two exposed columns of York and Rudolf Ritter von Otto while the other three southern columns remained strangely inert.[15]

Battle

Preparations

On 19 May, the Allied army returned to its camps around Tournai after the defeat at Tourcoing. Emperor Francis and his Austrian generals were disheartened while the Coalition members blamed each other for the fiasco. The British troops, in particular, were angry with the Austrians for leaving them in the lurch. York's adjutant general, James Henry Craig wrote to the British War Office in disgust, "It is impossible to bring the Austrians to act except in small corps. I lament that we should become victims of their folly and ignorance." Nevertheless, the principal Coalition leaders resolved to attack again in the direction of Mouscron.[16]

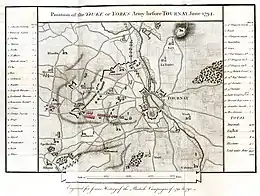

Coburg distributed the Coalition army around Tournai in an outer outpost line and in an inner circle of entrenchments. From south to north, the outpost line ran through the villages of Camphin-en-Pévèle, Baisieux, Willems, Néchin, Leers, Estaimpuis, Saint-Léger, and Spiere (Espierres) on the Scheldt River. From north to south, the inner line ran along the line Froyennes, Marquain, Lamain, the Saint-Martin suburb, and the Tournai citadel.[16]

Pichegru arrived on the scene the day after Tourcoing, and, oddly enough, received credit for the victory at the time. He now ordered an attack on the Coalition army at Tournai. Pichegru detailed Moreau's division to hold Courtrai and the line of the Lys River with the brigades of Dominique Vandamme and Philippe Joseph Malbrancq. These two units would keep Clerfayt from interfering with the operation. Moreau's third brigade under Nicolas Joseph Desenfans watched Ypres. Jan Willem de Winter's brigade from Souham's division would hold Helkijn (Helchin) and maintain the connection with Moreau.[17] Souham's division was ordered to attack the Coalition right (north) flank near Spiere and Leers while Bonnaud's division would assail the center near Templeuve. Osten's division was directed to demonstrate against the Coalition left (south) flank near Baisieux.[18]

Action

The battle began at 5:00 am on 22 May 1794, according to Ramsay Weston Phipps,[17] or between 6:00 and 7:00 am according to John Fortescue.[18][note 1] From left to right, Souham directed the brigades of Herman Willem Daendels, Macdonald, Henri-Antoine Jardon, Jean François Thierry, and Louis Fursy Henri Compère. Macdonald controlled both his own brigade and that of Jardon. Daendels marched along the Courtrai-Tournai highway toward Warcoing while Macdonald advanced from Aalbeke toward Saint-Léger.[17] On the north flank, Daendels' soldiers struck Georg Wilhelm von dem Bussche's Hanoverians at Spiere and forced them back. The Hanoverians withdrew to the east bank of the Scheldt via the bridge at Warcoing thanks to the support of Henry Edward Fox's British brigade[19] (14th Foot, 37th Foot, 53rd Foot).[20]

Daendels considered crossing to the east bank of the Scheldt, but abandoned that plan.[21] Instead, he burned the still-intact bridge and posted his brigade at Pecq.[22] Macdonald led five cavalry regiments forward, but these were stopped by artillery fire. Supported on his right by Thierry and Compère, Macdonald sent his infantry to assault Pont-à-Chin which became the focus of the most intense fighting of the day. Bonnaud sent the brigade of Jean-Baptiste Salme to assault an artillery position at Blandain while Osten moved from Willems against the Coalition's southern flank. Salme's attack was repulsed in confusion as were other French attempts to overpower the Coalition center and left. The left wing of the Allied army was commanded by Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen.[23] The demonstration against the Coalition left flank was executed so weakly that the Allies were able to send troops from there to areas more directly threatened.[21]

Buoyed by their recent victory at Tourcoing, the French fought tenaciously. However, Pichegru gave little overall direction to the battle. An Allied officer wrote that the musketry and artillery fire was more intense than the oldest soldier had ever seen.[24] However, casualties were relatively light as both sides had fought in relatively dispersed formations and skirmish lines. The attacks by Thierry and Compère mostly failed, but some of Thierry's skirmishers reached a position near Froyennes where they held their ground until 5:00 pm. Macdonald introduced a novel tactic by employing artillery near the front of his attack columns.[23] Macdonald's troops captured Pont-à-Chin four times and were driven out each time. Finally, they captured the place again.[21] By evening, the French held Pont-à-Chin, Blandain, and La Croisette Hill. Coburg ordered that those positions must be recaptured, especially Pont-à-Chin, French possession of which simultaneously cut the highway between Tournai and Courtrai, permitted them to interdict any river transport on the Scheldt, and gave them an intact crossing over the Scheldt, far too close to Tournai for comfort.[18] If the French solidified their hold on these places, it would severely limit Allied freedom of manoeuvre and communications towards the north while also threatening penetration of the area they were meant to protect, east of the Scheldt.

At 7:00 pm, York committed Fox's brigade and seven Austrian battalions to retake Pont-à-Chin.[21] Fox's brigade had been mauled at Tourcoing. As the British infantry passed to the attack, their gallant bearing was so impressive that they were cheered by nearby Austrian units. Under the assault, Macdonald's troops panicked and fled. British artillery rapidly deployed and its effective fire prevented the French from regrouping.[25] Fox's brigade seized both Pont-à-Chin and a ridge behind it, as well as seven guns.[18] Macdonald covered his retreat with three battalions.[23] Pichegru and his staff, thinking the position was secure, were having dinner in a house near Pont-à-Chin. Suddenly, there was a warning, "Les Anglais, les habits rouges!" (The English, the red-coats!) The French officers bolted for their horses, some jumping through the windows in their haste to get away. The French withdrew from the field and the last firing ceased at 10:00 pm.[25]

Results

Gaston Bodart stated that the Allies sustained 3,000 casualties or 6% out of an effective strength of 50,000.[26] Smith asserted that the Coalition forces lost 3,000 casualties out of 28,000 troops present. Hanoverian losses numbered 27 killed, 237 wounded, and 154 missing, plus 81 horses killed. Combined Austrian and British losses were 1,728 killed and wounded, and 565 missing. The French suffered 5,500 killed and wounded, plus 450 men and 7 guns captured out of strength of 45,000 troops.[27] Fortescue noted that French losses numbered 6,000 men and 7 guns, and that Fox's brigade lost 120 casualties out of the fewer than 600 that it took into action. Much of the fighting was done in dispersed order, which resulted in fewer casualties than otherwise might have occurred.[28] Phipps maintained that the Allies lost 4,000 men, including 196 British soldiers, of which 193 were from Fox's brigade. The French suffered 6,000 or more casualties and 7 guns out of a total of 62,000 soldiers. Robert Wilson reported that he counted 280 headless French corpses in an orchard where they were killed by the fire from an Austrian artillery battery.[29]

On 23 May, Mack resigned his position as Coburg's chief-of-staff and left the army. In his opinion, the reconquest of the Austrian Netherlands was a lost cause. Mack's replacement was Christian August, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont who already favored the abandonment of the Austrian Netherlands. On 24 May, a council of war was held by Francis in which he presented the situation in a bad light, with only York urging a new attack on the French. That same day, Kaunitz routed the French right wing on the Sambre at the Battle of Erquelinnes. Events in Poland began to exert their influence on Emperor Francis.[20] On 25 March 1794, the Kościuszko Uprising broke out in Poland and rapidly spread. This rebellion took Francis, Catherine I of Russia and Frederick William II of Prussia by surprise. Catherine asked Francis for assistance and Prussia withdrew 20,000 soldiers from the war against France.[30] At imperial headquarters, one faction led by Coburg wanted to persevere with the war with France, while another faction that included Waldeck wanted Austria's focus turned east toward Poland in order to thwart its Prussian rival.[31] On 29 May, Francis abruptly left the army to return to Vienna, dismaying his officers and soldiers. Coburg retained command of the Coalition forces, but only with great reluctance.[32]

Notes

- Footnotes

- Fortescue wrote that the battle occurred on 23 May, but on the next page changed the date to 22 May.

- Citations

- Fortescue 2016, p. 86.

- Phipps 2011, p. 275.

- Phipps 2011, p. 284.

- Phipps 2011, p. 292.

- Fortescue 2016, pp. 84–85.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 87.

- Smith 1998, p. 76.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 102.

- Phipps 2011, p. 293.

- Phipps 2011, pp. 294–295.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 108.

- Smith 1998, pp. 79–80.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 112.

- Phipps 2011, p. 299.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 127.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 130.

- Phipps 2011, p. 309.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 131.

- Cust 1859, p. 201.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 132.

- Phipps 2011, p. 310.

- Cust 1859, pp. 201–202.

- Cust 1859, p. 202.

- Phipps 2011, pp. 309–310.

- Phipps 2011, p. 311.

- Bodart 1916, p. 42.

- Smith 1998, p. 80.

- Fortescue 2016, pp. 131–132.

- Phipps 2011, pp. 309–311.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 109.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 110.

- Fortescue 2016, p. 133.

References

- Bodart, Gaston (1916). "Losses of Life in Modern Wars: Austria-Hungary, France". Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- Cust, Edward (1859). Annals of the Wars: 1783–1795. Vol. 4. London: Gilbert & Rivington. pp. 198–201. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- Fortescue, John W. (2016) [1906]. The Hard-Earned Lesson: The British Army & the Campaigns in Flanders & the Netherlands Against the French: 1792–99. Leonaur. ISBN 978-1-78282-500-5.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011) [1926]. The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume I The Armée du Nord. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-24-5.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

Further reading

- Agthe, Thilo C. (2006). "Liste der gebliebenen, und an Blessuren oder Krankheiten verstorbenen Mannschaft der in Englischen Sold getretenen Hannoverschen Truppen vom Monat Mai 1794" (in German). denkmalprojekt.org. Retrieved 27 June 2021. This lists individual Hanoverian army casualties in May 1794.

- Anon. (1796), An Accurate and Impartial Narrative of the War, by an Officer of the Guards, London

- Brown, Steve (2021). The Duke of York's Flanders Campaign: Fighting the French Revolution 1793-1795. Havertown, Pa.: Pen and Sword Books. pp. 135–136. ISBN 9781526742704. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- Burne, Alfred (1949), The Noble Duke of York: The Military Life of Frederick Duke of York and Albany, London: Staples Press

- Coutanceau, Michel Henri Marie (1903–1908), La Campagne de 1794 a l'Armée du Nord, Paris: Chapelot (5 Volumes)

- Jones, Captain L. T. (1797), An Historical Journal of the British Campaign on the Continent in the Year 1794, London

External links

Media related to Battle of Tournai at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Tournai at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Battle of Tourcoing |

French Revolution: Revolutionary campaigns Battle of Tournay (1794) |

Succeeded by Battle of Fleurus (1794) |