Bean Station, Tennessee

Bean Station is a town in Grainger and Hawkins counties in the state of Tennessee, United States.[9][7] As of the 2020 census, the population was 2,967.[10]

Bean Station | |

|---|---|

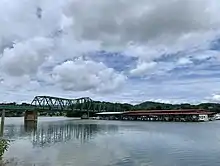

Main Street (Old US 11W) in Bean Station | |

Seal | |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto: "A Historical Crossroad" | |

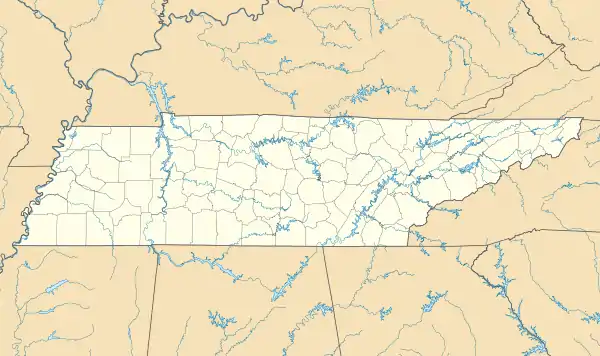

Location of Bean Station in Grainger and Hawkins counties in Tennessee | |

Bean Station  Bean Station | |

| Coordinates: 36°20′37″N 83°17′03″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Tennessee |

| Counties | Grainger, Hawkins |

| Founded | 1776 |

| Incorporated | 1996 |

| Founded by | William Bean[3] |

| Named for | Bean family settlement[4] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Ben Waller |

| • Vice Mayor | Jeff Atkins |

| • Town Council | Aldermen |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.99 sq mi (15.52 km2) |

| • Land | 5.99 sq mi (15.51 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,112 ft (339 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 2,967 |

| • Density | 495.41/sq mi (191.27/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 37708, 37811 |

| Area codes | 865, 423 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2403829 |

| FIPS code | 47-03760 |

Established in 1776 as a frontier outpost by William Bean, it is considered one of the earliest permanently settled communities in Tennessee. It would grow throughout the rest of the 18th century and the 19th century as an important stopover for early pioneers and settlers in the Appalachia region due to its strategic location on the crossroads of Daniel Boone's Wilderness Road and the Great Indian Warpath.

During the American Civil War, the town would be the site of the final battle of the Knoxville campaign, before Confederate forces surrendered to a Union blockade in nearby Blaine. In the early 20th century, Bean Station would experience renewed growth with the development of the Tate Springs mineral springs resort, investment from U.S. Senator John K. Shields, and the Peavine Railroad, which provided passenger rail service connecting the town to Knoxville and Morristown.

In the 1940s, the town would be completely inundated by the Tennessee Valley Authority for Cherokee Dam with nearly all of its residents removed via eminent domain and federal court orders. Following its inundation, it would shift to the new junction of U.S. Route 11W and U.S. Route 25E, becoming a popular lakeside community, and a commuter town for the city of Morristown in neighboring Hamblen County. Citing annexation attempts by Morristown, Bean Station would incorporate into a town in 1996.

It is part of the Kingsport Metropolitan Statistical Area, Knoxville Metropolitan Statistical Area, and Morristown Metropolitan Statistical Area.[11]

History

Early years and settlement

.jpg.webp)

In 1775, pioneers Daniel Boone and William Bean observed what is now Bean Station from the top of Clinch Mountain while on a hunting and surveying excursion.[3] During the Revolutionary War, Bean would serve as a captain for the Virginia militia, and would be awarded over 3,000 acres in the German Creek valley where he surveyed and camped at previously with Boone in 1776.[3] Bean would later construct a four-room cabin at this site, which served as his family's home, and as an inn for prospective settlers, fur traders, and longhunters.[12] This inn and its area would have many names: Bean's Cabin, Bean's Crossroads, and Bean's Station,[12] thus establishing the first reportedly permanent settled European-American community in present-day Tennessee.[13] Following William Bean's death in May 1782, Bean Station would later grow into a frontier outpost established in the late 1780s by the sons of Bean. This outpost included the cabin that the Bean family resided in, a tavern, and a blacksmith's shop operated by Bean's sons.[3][12] The settlement was situated at the intersection of the Wilderness Road, a north–south pathway constructed in the 1780s that roughly followed what is present-day U.S. Route 25E, and the Great Indian Warpath, an east–west pathway that roughly followed what is now U.S. Route 11W.[14][15][16] This heavily trafficked crossroads location made Bean Station an important stopover for early American travelers, with taverns and inns were operating at the station by the early 1800s.[14] By 1821, the pathway of the Wilderness Road from the Cumberland Gap to Bean Station would be established as the Bean Station Turnpike, and would receive state funding while it being a privately owned toll route due to its importance for early interstate travel in the Appalachia region.[17]

Establishment as tourist center

Throughout the 1800s, Bean Station attracted the attention of numerous merchants and businessmen who appealed to the travelers that used the community's significant crossroads of the designated Wilderness Road and the East-West Road (Broadway of America) which replaced the Great Indian Warpath.[14][18] In 1825, Bean Station Tavern, with a 40-room capacity, wine cellar, and ballroom, was constructed at the crossroads near the fort that Bean family would construct when the area was first settled in 1776. The tavern, was considered to be one of the largest of its time between New Orleans and Washington, D.C., and housed several famous guests including U.S. Presidents Andrew Jackson, Andrew Johnson, and James K. Polk.[14]

The tavern, being popular with politicians while campaigning or traveling across the country, would provide heated encounters with political rivals who would stay at the tavern as well. One of the more notable incidents regarding such scenarios involved U.S. President Andrew Jackson, who arrived via stage coach with the intent to have lunch with the owner of the tavern. Upon his arrival, Jackson would see one of his political rivals on the front porch of the Bean Station Tavern. Jackson would cancel the lunch, and explain his regrets to the wife of the tavern's owner, stating, "It would be a shame for the President of the United States to get killed, or to kill somebody."[19]

The main portion of the tavern would be destroyed from a major fire on Christmas night in 1886.[20]

When the Tennessee Valley Authority announced the impounding of the Holston River and the site of Bean Station in the 1940s, efforts began to deconstruct and relocate the tavern to a new relocation site of the community.[21] Following the cancellation of the Bean Station relocation project, the parts would remain in storage long-term at a warehouse located near the western intersection of US 25E and US 11W.[21][20]

In 1961, the TVA proposed plans to create a 50-acre historical park near the western interchange of US 11W and US 25E with the tavern rebuilt on-site following efforts led by a Morristown historical group.[22] However, these plans would be scrapped following the loss of the original tavern materials due to the deterioration from the lengthy storage period, rendering the plans infeasible.[23][21]

The TVA-owned land reserved for the Bean Station Tavern park would be constructed into a public baseball park on behalf of Grainger County officials following the inability to construct the tavern.[23]

Battle of Bean’s Station and the Civil War

During the Civil War, the Battle of Bean's Station took place in the westernmost area of the community on December 14, 1863. Confederate Army General, James Longstreet, attempted to capture Bean Station en route to Rogersville after failing to drive Union forces out of Knoxville. Bean Station was held by a contingent of Union soldiers under the command of General James M. Shackelford. After two days of gruesome fighting, Union forces were forced to retreat.[14]

Tate Springs Resort

In the post-Civil War era, a businessman named Samuel Tate constructed a hotel west of Bean Station that became the main focus of a resort known as Tate Springs.[24] Around the late 1870s, the property was purchased by Captain Thomas Tomlinson, a Union army veteran who served in the Battle of Bean's Station, would take up an interest in the Bean Station community, and transformed the property into a vast resort, focused on a large Victorian-style luxury hotel, that advertised the supposed healing powers of its mineral spring’s water.[25] During its heyday, the resort complex included over three-dozen buildings, a 100-acre (40 ha) park, and an 18-hole golf course.[26] The resort had attracted some of the wealthiest people in America during this time.[24] The resort declined during the Great Depression and closed in 1941.[27] In 1943, the hotel site would be redeveloped into a school and orphanage known as Kingswood. The main hotel structure was destroyed by fire in 1963, and the only remnants of the complex are the cabins of the site, the pool bathhouse, and the springhouse, the last of which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[27] The Tate Springs site still runs as the Kingswood orphanage as of 2021.[27]

Peavine Railroad and redevelopment efforts

From the late 19th century until the early 20th century, Bean Station was a stop along the Knoxville and Bristol Railroad, commonly known by locals as the Peavine Railroad. The railroad was a branch line of the Southern Railway that ran from Morristown to Corryton, a bedroom community outside of Knoxville.[28] The Peavine Railroad had first operated between Morristown and Bean Station, with construction complete in 1893.[16] The completion of the railroad would influence the formation of the Bean Station Improvement Company (BSIC), a redevelopment company, led by resident and former U.S. Senator John K. Shields, with the intent to bring life back to the community.[16] The BSIC would lay the groundworks of a town street grid system, sell property for development, and pitch the community in widely distributed advertisements and brochures regarding the past, present, and future of Bean Station. The company would help fund and propose plans to further the town as an important multimodal distribution rail-and-road center, such as an extension of the Peavine Railroad across Clinch Mountain to the Cumberland Gap, and northeast to Bristol. The extension plans to both the Cumberland Gap and Bristol would not come to fruition,[16] but rail access would be extended west through Grainger County to Knoxville.[29] The Tate Springs resort located in (then) eastern Bean Station, had its peak popularity between the 1890s and 1920s when the Peavine Railroad provided passenger rail connections to the site.[30]

The Peavine Railroad would end service in 1928, and the lines would be either demolished or washed out following the inundation of the Holston River by the Tennessee Valley Authority in 1942.[29]

TVA and community displacement

The construction project of Cherokee Dam by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) several miles downstream along the Holston River had plans that included impounding the site where the town was originally settled.[31] Because of its historical significance, size, and potential relocation problems presented with Bean Station, officials from the TVA, Tennessee state government, historians, and concerned community members gathered in public forums to discuss the future of the town, and its relocation efforts in 1941 before the valley would be flooded the following year.[33]

A commission consisting of state planning and TVA personnel would host town hall meetings during the spring of 1941 in Bean Station to review and developed plans for sites for Bean Station to relocate to as a planned village, similar to the planning process for the 'model town' of Norris for TVA's earlier Norris Project in the 1930s.[34] After controversy arose following failed negotiations from unwilling property owners for the relocation sites, and reluctance from most Bean Stationers to relocate in a community effort, the community relocation project would be abandoned, with most citizens relocating on their own will.[31]

Of the estimated 200 families who lived at the original site of Bean Station,[32] nearly 150 or 87.5% were mandated to move via eminent domain.[31] Many houses, 20 businesses, and Clinchdale, the estate of Senator John K. Shields,[35] were demolished or moved, and at least one historical structure had to be relocated.[14][31] In the project report established by the TVA following the Cherokee Project's completion, the agency would cite the opposition from residents in the Bean Station region as the biggest hurdle during the entire project, stating, "This stability of tenure and reluctance to move complicated the problem of relocation and removal. This area included the town of Bean Station, and the Noeton-Crosby area in Grainger County."[31]

Community resistance and resilience, incorporation, and present day

Following the inundation of the original site of Bean Station in 1942 and the failed plans by TVA and state officials relocating to new site, Bean Station unofficially shifted to the relocated intersection of US 25E and US 11W near the Grainger-Hawkins border.[36] Through the mid-20th century, Bean Station saw a revived growth in population and economic progress as the community's principal transportation routes US 11W and US 25E were used prominently for the nationwide trucking industry, making the community a site of new truck stops and motels.[37]

By the 1950s, Bean Station would be at the highlight of controversy again regarding the Interstate 81 (I-81) corridor of the Interstate Highway System, originally planning to follow the US 11W route through Bean Station from Bristol into Knoxville. Farmers in the community and surrounding area opposed the project. Facing the opposition and swooning by neighboring Greene and Hamblen county officials, roadway engineers and planners had I-81 redirected south of the community and the 11W corridor.[36][38]

As the region's economy began to diversify, manufacturing soon took over agriculture as the area's main source of income.[39] As the community witnessed increased development along routes 25E and 11W and the emergence of manufacturing facilities by the mid-century,[23] the community would attempt to incorporate into a city in 1964.[40] Residents rejected to incorporate in a 153 to 94 vote.[40] In 1967, community residents organized and chartered the Bean Station Volunteer Fire Department.[1] Eight years later, the Bean Station Volunteer Rescue Squad would be established to service the community.[1]

On May 13, 1972, 14 people were killed and 15 injured in a head-on collision between a double-decker Greyhound bus and a tractor-trailer on U.S. Route 11W in Bean Station.[41][42] The accident is considered one of the deadliest and worst traffic collisions in the history of the state of Tennessee.[43][44] The collision, the deadliest in state history, led to outcry from politicians and citizens in Bean Station calling for traffic safety and infrastructure improvements, such as the widening of 11W and other state highways, and the completion of Interstate 81 in Tennessee in order to alleviate the congestion that 11W experienced being the main thoroughfare between Knoxville and Bristol.[45]

Following the completion of Interstate 81 in neighboring Morristown in December 1974, the community would witness a massive decline in business following the decreased traffic on 11W.[37] Most truck stops, gift stores, and motels would close in Bean Station following the reported 60% decline in business in the community.[37]

In 1977, residents in Bean Station would petition to incorporate into a city again, with new boundaries including portions of the neighboring Mooresburg community across the Hawkins County line. The proposal would be rejected in a 291 to 160 vote.[47]

US 25E would experience an opposite scenario to 11W in Bean Station, as the completion of I-81 led to increased congestion on US 25E from its junction with I-75 in Kentucky through Bean Station into Morristown, due to the route becoming a popular alternate corridor for truckers bypassing I-75 in Knoxville.[23] Increased sprawled residential development in Bean Station led to the two-lane 25E to be overloaded with commuters to neighboring Morristown.[23] In the 1980s, US-25E would be widened to a four-lane limited-access highway from Lakeshore Drive to across Cherokee Lake into Morristown, and from the gap at Clinch Mountain to the base near the westernmost junction of 11W and 25E in Bean Station.[48] In 1995, US-11W and US-25E were relocated and widened into a four-lane limited-access highway,[23] bypassing Bean Station's central business district and prompting several businesses to relocate near the new bypass.[39]

In the mid-1990s, rumors regarding portions of southern Bean Station being possibly annexed into neighboring Morristown spread throughout the community, leading residents to petition a third incorporation election in 1994.[46][1] In 1996, community members voted by referendum to incorporate Bean Station into a city with a population of 2,171 residents.[39][49] The measure was decided in a large margin, with 627 in favor of incorporation and 142 against.[50]

On May 23, 2013, Down Home Pharmacy, a pharmacy located in downtown Bean Station, would be the site of an armed hostage and robbery. The act would be committed by an ex-police officer for the town, who would kill two in an execution-style shooting, and injure two others after robbing the pharmacy for opioids.[51] The following day, a vigil at the Bean Station town hall would be held for the four victims with an estimated attendance of 300 individuals.[52]

Geography

Bean Station is located in rural easternmost Grainger County, 45 miles northeast of Knoxville,[53] where it borders the unincorporated community of Mooresburg at the line between Grainger and Hawkins counties. The town is situated in the Richland Valley (also known as Mooresburg Valley) with Clinch Mountain to the north and Cherokee Lake to the south. In the western of portion of Bean Station adjacent to Kingswood Home for Children on the Tate Springs resort site, two major highways merge, with U.S. Route 25E entering from the northwest, and U.S. Route 11W entering from the southwest. From this point, US-25E leads over Clinch Mountain 20 miles (32 km) to Tazewell in Claiborne County, while US-11W runs west through the Richland Valley 11 miles (18 km) to Rutledge, the seat of Grainger County. The highways split again just south of Bean Station's central business district, with 11W bypassing the business district and continuing northeastward 17 miles (27 km) to Rogersville, and 25E continuing southward across Cherokee Lake into Hamblen County, 10 miles (16 km) to Morristown.

Tennessee State Route 375 (also known as Lakeshore Drive) also intersects US-25E south of the business district, which traverses into several of Bean Station’s affluent outskirt lakefront neighborhoods and subdivisions.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Bean Station has an area of 5.4 square miles (14.0 km2), of which 0.436 acres (1,763 m2), or 0.01%, are water.[10] The town limits include Wyatt Village, located next to an arm of Cherokee Lake along US-25E south of downtown, and portions of Tate Springs located near US-11W and Briar Fork Creek on Cherokee Lake. The town limits stretch 8 miles (13 km) along the heavily trafficked US-25E to the Olen R. Marshall Memorial Bridge across Cherokee Lake,[54] and 4 miles (6.4 km) along US-11W to Bean Station Elementary School.

Since 2014, portions of unincorporated Hawkins County in the Mooresburg area have been annexed into the town limits.[55]

Neighborhoods

- Bayside

- Campbell Heights

- Clinchview Landing

- Country Club Hills

- Crosby Park

- Gammon Springs

- Hillview Acres

- Lakeview Estates

- Leon Rock

- Livingston Heights

- Meadow Branch

- Meadow Creek Estates

- Shields Crossing

- Tanglewood

- Tate Springs

- Wyatt Village

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2,356 | — | |

| 2000 | 2,514 | 6.7% | |

| 2010 | 3,092 | 23.0% | |

| 2020 | 2,967 | −4.0% | |

| Sources:[56][8] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 2,762 | 93.09% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 15 | 0.51% |

| Native American | 3 | 0.1% |

| Asian | 5 | 0.17% |

| Other/Mixed | 109 | 3.67% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 73 | 2.46% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 2,967 people, 1,144 households, and 774 families residing in the city.

2010 census

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 3,092 people, 1,149 households, and 827 families residing in the town.

96.8% were White, 0.6% Black or African American, 0.5% Native American, 0.1% Asian and 0.7% of two or more races. 2.3% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 2.88. 25% of households had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.8% were married couples living together, 6.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 13.9% were female householders with no husband present. 28% of households were non-families. The median age of residents in the town was 47.8. 21.7% of residents were under the age of 18, and 16.2% were age 65 years or older.

Economy

In its retail and commercial markets, Bean Station has a small selection of restaurants and stores. A large cluster of firework stores are located throughout the town due to Grainger County being among the few counties in Tennessee allowing the sale of fireworks.[2][58] A family-operated IGA Market is the only grocery store in Bean Station area.[59]

Bean Station is home to a furniture manufacturing facility,[60] a Clayton Homes manufacturing facility,[61] and a construction materials supplier.[62]

In 2010, 72% of the town’s population was reported to commute outside of Grainger County for work, with most finding employment in Morristown.[63] The average commute time for Bean Station residents is 24 minutes.[64]

Arts and culture

Since 1996, the town hosts an annual harvest festival in its downtown district celebrating the area's agricultural and craftsmanship.[49] Thousands of guests attend.[65][66] In 2007, a Guinness World Record for the largest pot of beans was established at the 11th Harvest Pride festival, with the pot holding 600 US gal (2,300 L) of baked beans.[65][67][68]

Historic sites

- Battle of Bean's Station site[69]

- Original Bean Station settlement site, Bean cabin site, and historical marker[70]

- Tate Springs resort site and Tate Springs Springhouse[1]

Parks and recreation

The town is popular with boaters and anglers due to its access to Cherokee Lake.[49] A public golf course is also located within the town limits.[49]

Parks and public recreation areas include:

Government

Bean Station uses the mayor-aldermen system, which was established in 1996 when the town was incorporated. It is governed locally by a five-member Board of Mayor and Aldermen. The citizens elect the mayor and four aldermen to four-year terms. The board elects a vice mayor from among the four aldermen.[73]

Bean Station is represented in the 10th District of the Tennessee House of Representatives by Rick Eldridge, a Republican.

It is represented in the 8th District of the Tennessee Senate by Frank Niceley, also a Republican.[74]

Bean Station is represented in the United States House of Representatives by Republican Tim Burchett of the 2nd congressional district.[75]

Education

Bean Station Elementary School, located at the westernmost part of the town, is operated by the Grainger County Department of Education. Elementary students attend Bean Station Elementary, middle school students attend Rutledge Middle, and high school students attend Grainger High School in Rutledge, along with other students in the Grainger County Schools District, excluding the Washburn area.[76]

Kingswood Home for Children, located in the Tate Springs area of Bean Station, operates as a children’s home.[77]

Media

Newspaper

- Grainger Today, weekly news publication based in Bean Station reporting Grainger County related news; in operation since 2004.[78]

Infrastructure

Utilities

Bean Station Utility District, (BSUD), a municipal utilities company, connects the town and portions of eastern Grainger County with municipal water services.[79]

Appalachian Electric Cooperative (AEC), a utilities company based out of New Market in neighboring Jefferson County, provides electricity and the option for fiber broadband internet for all of Bean Station, portions of Hamblen County (including portions of Morristown), Jefferson County (including New Market, Baneberry, Jefferson City, Dandridge, and White Pine), and eastern Grainger County (including Rutledge).[80][81] AEC, as of June 2018, provides services to 46,000 customers.[81]

Sewer

Bean Station, as of 2021, does not have access to public sewer.[82] Since the town's incorporation, officials have expressed interest, and have proposed several unsuccessful attempts towards constructing a sewage treatment system to stimulate economic development.[49][83] In 2019, a master plan conducted by a Knoxville based engineering firm found that there was a definite need for public sewer service in Bean Station, as most existing septic tank systems in the town have reported failures posing severe health hazards to residents, and development opportunities providing job and economic growth are limited with the lack of public sewer.[82]

In January 2021, proposals for a sewer line extension by Morristown Utilities System into south Bean Station were approved by the town council.[84] In May 2021, the project would be suspended temporarily following abandonment from businesses and lack of communication with Morristown Utilities from BSUD.[85]

Transportation

All U.S. routes and state routes in Bean Station are maintained by the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) in TDOT Region 1, which consists of 24 counties in the East Tennessee region.[86] Streets in the town are maintained by the Bean Station Street Department.[87]

Principal highways

US 11W /

US 11W /  SR 1 (Lee Highway)

SR 1 (Lee Highway) US 25E /

US 25E /  SR 32 (East Tennessee Crossing Byway, Appalachian Development Corridor S)

SR 32 (East Tennessee Crossing Byway, Appalachian Development Corridor S) SR 375 (Lakeshore Drive)

SR 375 (Lakeshore Drive)

Notable people

- Peter Ellis Bean - filibuster[90]

- William Bean - longhunter, namesake, and town founder[3]

- Robert E. Preston - Director of United States Mint[91]

In popular culture

Bean Station was referenced on the NBC police procedural comedy series Brooklyn Nine-Nine, as one of the secondary characters on the show, Bill Hummertrout, cited it as his hometown.[92]

The 1981 horror film, The Evil Dead, had filmed part of its opening scenes in northern Grainger County, and in Bean Station along Old U.S. Route 25E near Bean Station Elementary School.[93]

References

- Grainger County Heritage Book Committee (January 1, 1999). Grainger County, Tennessee and Its People 1796-1998. Walsworth Publishing. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Rankin, Joe (June 30, 1977). "Business Booming Again in Grainger". Kingsport Times-News. p. 1, 10. Retrieved October 29, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Coffey, Ken (October 19, 2012). "The First Family of Tennessee". Grainger County Historic Society. Thomas Daugherty. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- Miller, Larry (2001). Tennessee Place Names. Indiana University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-253-33984-7. Retrieved June 25, 2020 – via Google Books.

- University of Tennessee, Municipal Technical Advisory Service. "Bean Station". MTAS.tennessee.edu. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- "City of Bean Station". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- Bobo, Jeff (February 5, 2020). "2020 a big year for Hawkins BOE, municipal elections". Kingsport Times-News. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

In Bean Station, which has a small section in Hawkins County, the alderman seats held by Patsy Harrell and Jeff Atkins are up for re-election.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Bean Station city, Tennessee". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- "Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- Barksdale, Kevin (July 11, 2014). The Lost State of Franklin: America's First Secession (E-book). University Press of Kentucky. p. 19. ISBN 9780813150093. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- Clouse, Allie (May 27, 2021). "From Davy to Dolly: 225 years (and more) of Tennessee's storied history". Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- Coffey, Ken. "History of Bean Station". Town of Bean Station. Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- Brown, Fred (2005). Marking Time (Paperback). University of Tennessee Press. pp. 99–101. ISBN 9781572333307. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Lane, Ida M. (December 1, 1929). "Once The Teeming Crossroads Of The Wilderness, Bean Station Now Lapsed Into Village Peace". Knoxville News Sentinel. p. 23. Retrieved November 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Private Acts: Highways & Roads". Grainger County Genealogy & History. May 9, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- Ball, Randy; Wolfe, Terry (November 19, 2013). Tate Springs 1898: Town of Bean Station, Tennessee. Town of Bean Station. p. 4. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- Price, Shirley (April 22, 1967). "Bean Station Tavern, Where Old Hickory Missed His Lunch". Kingsport News. p. 4. Retrieved March 27, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Grady, Jamie (1973). William Bean, Pioneer of Tennessee, and His Descendants. University of Wisconsin, Madison. pp. 6–8. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- Howes, Robert (January 1, 1944). The Bean Station Tavern Restoration Project. Knoxville: Tennessee Valley Authority, Department of Regional Studies. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- "Restore Bean Station Tavern, Create Park, Morristown Asks". Knoxville News Sentinel. March 19, 1961. p. 4. Retrieved October 29, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- SR-32, US-25E, Appalachian Corridor S, Grainger County Environmental Impact Statement · Volume 1. United States Federal Highway Administration. 1981. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Seitz, Robert. "Tate Springs Resort and Hotel 1865-1941". Kingswood School History. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- Phillips, Bud (July 18, 2010). "Tate Springs was once a popular health resort". Bristol Herald Courier. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "Spring Histories". Tennessee State Library and Archives. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- Beasley, Ellen (January 8, 1973). "NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- Faulkner, Charles (1985). "Industrial Archaeology of the "Peavine Railroad": An Archaeological and Historical Study of an Abandoned Railroad in East Tennessee". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. Tennessee Historical Society. 44 (1): 40–58. JSTOR 42626500.

- Hill, Howard (January 20, 1957). "The Old Peavine Railroad". Morristown Daily Gazette and Mail. p. 6. Retrieved August 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- West, Carroll Van (1995). Tennessee's Historic Landscapes: A Traveler's Guide. University of Tennessee Press. pp. 166–167. ISBN 9780870498817 – via Google Books.

- Tennessee Valley Authority (1946). The Cherokee Project: A Comprehensive Report on the Planning, Design, Construction, and Initial Operations of the Cherokee Project. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 32, 249 – via Google Books.

- Coffey, Ken (May 20, 2018). "Lost by water: Bean Station History". Grainger Today. Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- Caruthers, Amelia (April 26, 1942). "Cherokee Lake Will Flood Site of East Tennessee Shrine, But Bean Tavern is 'Packed Away,' All Ready To Be Rebuilt". Knoxville News Sentinel. p. 26. Retrieved November 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Turner, Jessie (July 13, 1941). "Tennessee Agencies Unite to Preserve Historic Bean Station". Chattanooga Daily Times. Retrieved March 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Robinson, Bonnie (April 26, 1942). "Historic Bean Station, Oldest House in This Section, Fine Homes, and Other Landmarks Will Disappear in Cherokee Dam Lake". Knoxville News Sentinel. p. 26. Retrieved November 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Grainger County, 1796-1976: The Only Tennessee County Named for a Woman. Grainger County Bicentennial Committee. 1976. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Rankin, Joe (July 17, 1977). "They're Waiting For The Trucks". Kingsport Times-News. p. 1, 10. Retrieved October 29, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Moore, B.H. (August 3, 1972). "Improve Highway 11W". Kingsport Times-News. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "A Brief History of Bean Station". City of Bean Station. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Voters Reject Incorporation". The Knoxville Journal. June 11, 1964. p. 13. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- "14 Die in Tennessee Bus Truck Crash". The New York Times. May 14, 1972. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Wolfe, Tracey (June 24, 2020). "Victim reunites with rescue workers 48 years after deadly crash". Grainger Today. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Lakin, Matt (August 26, 2012). "Blood on the asphalt: 11W wreck left 14 people dead". Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Ahillen, Steve (October 3, 2013). "Jefferson wreck echoes Tennessee's most deadly bus accident". Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- Smith, Bob (May 14, 1972). "11-W Disaster Brings New Highway Pleas". Kingsport Times-News. p. 1, 10. Retrieved February 20, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Downing, Shirley (September 21, 1997). "Towns". The Commercial Appeal. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- "Bean Station Plan Fails". Kingsport Times-News. September 19, 1977. p. 8. Retrieved October 19, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- SR-32, US-25E, Appalachian Corridor S, Grainger County: Environmental Impact Statement, Volume 2. Tennessee Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration. 1981 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "About Bean Station". City of Bean Station. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Bean Station votes to incorporate". Knoxville News Sentinel. November 6, 1996. p. A3. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- "Authorities confirm identities of alleged shooter, victims in Bean Station double homicide". Citizen Tribune. May 23, 2013. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- Coleman, Lance (May 24, 2013). "Police: Bean Station pharmacy victims shot execution-style". The Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- "Locator Map". City of Bean Station. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- Jacobs, Dan (May 23, 2010). "Murder Mysteries: Bean Station slaying still unsolved". Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- Bobo, Jeff (August 27, 2013). "Bean Station will seek referendum to annex Hawkins plant". Kingsport Times-News. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- "Census of Population and Housing: Decennial Censuses". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- "Bean Station, TN to Tazewell, TN". Walk Over States.

- "Holt's Food Center IGA". holtsfoodcenter.iga.com/. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- "Sexton Furniture Manufacturing LLC". Bloomberg. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- "Norris Homes by Clayton Homes". Norris Homes. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Vulcan Materials. "Facilities". vulcanmaterials.com. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- East Tennessee Development District (April 1, 2012). "Grainger County 2010 Census Report" (PDF). ETDD.org. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Bean Station, TN". DataUSA.io. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Cason, Steve. "City to cook the world's largest pot of beans" (PDF). City of Bean Station. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 9, 2008. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- Littleton, Wade (October 19, 2019). "Harvest Pride Festival attracts hundreds". The Citizen Tribune. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Branston, John (September 7, 2007). "Tennessee City Gassed Over World Record Pot of Beans". The Memphis Flyer. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- "Bean festival scores an appropriate sponsor". AdWeek. October 23, 2007. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- Morfe, Don (October 20, 2013). "Battle of Bean's Station". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- Morfe, Don (October 20, 2013). "Bean Station". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- "Cherokee Reservoir". Tennessee Valley Authority. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Boating Ramps and Access". Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "City Government". City of Bean Station. Archived from the original on April 22, 2011.

- "Senator Frank S. Niceley". capitol.tn.gov. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- "Our District". Congressman Tim Burchett. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- "Schools". Grainger County Schools. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- Lakins, Laura (October 14, 2020). "Kingswood Home for Children receives sidewalk and gazebo". Grainger Today. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "About Us". Grainger Today. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- "Business & Industry". Grainger County, Tennessee. Archived from the original on January 15, 2006. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- "Outage Map". Appalachian Electric Cooperative. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "Facts About Your Cooperative" (PDF). Appalachian Electric Cooperative. June 30, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Fulghum MacIndoe & Associates Inc. (March 12, 2019). "Bean Station, Tennessee Wastewater Treatment Master Plan" (PDF). Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- Littleton, Wade (March 13, 2019). "Bean Station officials talk sewer at special-called meeting". Citizen Tribune. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- Wolfe, Tracey (January 27, 2021). "Atkins re-elected vice mayor". Grainger Today. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- Lakins, Laura (May 19, 2021). "Potential sewer expansion suspended". Grainger Today. Archived from the original on May 19, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- "Find Information". Tennessee Department of Transportation. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- "Street Department". Town of Bean Station. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- "Bean Station North" (PDF). Tennessee Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration. 2004. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- "Bean Station South" (PDF). Tennessee Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration. 2004. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- Weems, John Edward. "Bean, Peter Ellis". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- Current History and Modern Culture: 1893. Vol. 3. Current History Company. 1894. p. 499 – via Google Books.

- Payne, Alex (June 6, 2020). "Brooklyn Nine-Nine's Secondary Characters, Ranked". CBR. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- "Locations". bookofthedead.ws. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

Further reading

- Tennessee Valley Authority. Population readjustment studies of Bean Station community, Grainger County, Cherokee area 1940.

- Tennessee Valley Authority. The Bean Station Tavern restoration project 1944.

- Coffey, Ken. The Wilderness Road, The First Family of Tennessee: and Other Stories That Need to be Told 2013.

- Ball, Randy & Wolfe, Terry. Tate Springs 1898: Town of Bean Station, Tennessee 2013.