Beatrice d'Este (1268–1334)

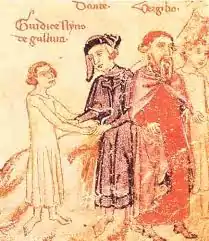

Beatrice d’Este (Ferrara, 1268 - Milan, 15 September 1334) was an Italian noblewoman, now primarily known for Dante Alighieri's allusion to her in Purgatorio, the second canticle of the Divine Comedy. Through her first marriage to Nino Visconti, she was judge (giudichessa) of Gallura, and through her second marriage to Galeazzo I Visconti, following Nino’s death, lady of Milan.

Biography

Beatrice was born in Ferrara in 1268. She was the daughter of the Marquis Opizzo II d’Este, of the Este family, who was also the lord of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio Emilia, and Jacopina Fieschi. Her brother was Azzo VIII. She was married off at a very young age to a man from Pisa named Nino Visconti, who was a judge in the district of Gallura in northeast Sardinia. Nino Visconti was also the grandson of Count Ugolino della Gherardesca.[1]

Nino died in 1296, only five years after his marriage to Beatrice. Nino and Beatrice only had one child: a daughter named Joanna, who was born in 1291. Beatrice returned to Ferrara after Nino’s death. Because she was a widow who only had a daughter and no male heir, she was placed in the responsibility and authority of her brother Azzo, who had a reputation for being unkind.[2] After returning to Ferrara, Beatrice was first engaged to one of the sons of Alberto Scotti, lord of Piacenza. This engagement was arranged by Azzo to use her sister’s status as a young widow to form a favorable alliance with a different family.[2] During the Middle Ages, women’s closest male relations would arrange marriages for them. After Beatrice’s father Obizzo II died, her brother Azzo had taken up this responsibility.

Azzo broke off this engagement in favor of a more advantageous relationship. At the time, Matteo I Visconti, lord of Milan, was also looking to establish an alliance with the Estensi, and managed to do so by arranging his son Galeazzo I Visconti’s marriage to Beatrice. Beatrice and Galeazzo married on 24 June 1300 in Modena, after which she moved to Milan. Beatrice and Galeazzo had one son, Azzone Visconti, who they named after Beatrice’s brother Azzo. Because of Beatrice’s second marriage, her daughter Joanna was stripped of her patrimony by the Ghibellines. Joanna's father, Nino, was a Guelph, and she stood in the way to the rivalry between the two groups. Ultimately, Joanna took shelter as a ward in the town of Volterra. Though the marriage was once again arranged by Beatrice's brother, it caused Beatrice to have the reputation for being a neglectful mother.

In 1302, the Visconti were exiled from Milan by the Torriani family. Beatrice, her husband, and the entire clan of the Milanese Visconti were in exile from 1302 to 1311. After returning to the city, in 1313, the emperor, Henry VII of Luxembourg, appointed Galeazzo the imperial vicar or Piacenza. Galeazzo left Piacenza to take the place of his retired father at the government of Milan. Beatrice and her son Azzone fled Piacenza to avoid revolts.

In 1327, the emperor Louis the Bavarian deposed Galeazzo, who was then exiled from Milan. He and his son were imprisoned in a castle in Monza. On 6 August 1328, while they were still in exile, Galeazzo died. Beatrice returned to Milan, and on 15 January 1329, her son Azzone was proclaimed lord of Milan.

Beatrice d’Este died on 15 September 1334 in Milan, and was buried in the church of San Francesco Grande, which was demolished in 1806. Her tomb had both the Gallura rooster and the Milanese viper sculpted on it: emblems of both husband’s families.[3]

In the Divine Comedy

Beatrice is now remembered primarily due to her presence in Dante's Divine Comedy. In Purgatorio, the second canticle of the poem, Dante and Virgil meet Nino Visconti in Ante-Purgatory, or the area outside St. Peter’s gate, which is reserved for people who neglected their spiritual and religious undertakings for the sake of their country. The souls here have to wait for a period that is same as their lifetime on earth before being allowed into Purgatory, so that they can begin their journey of purgation from their vices. Dante, who was friends with Nino while he was still alive, is glad to see him here and not in Hell, and treats him warmly.

In Purgatory, the sentences of the souls could be shortened and made better if those still alive on earth would pray for their souls. Nino begs Dante to make his daughter, Joanna, who is nine years old at the time in which the events of the Divine Comedy take place (the year 1300), to pray for his soul, since he fears his wife does not love him anymore:[4]

across the wide waves, ask my own Giovanna—

there where the pleas of innocents are answered—

to pray for me. I do not think her mother

still loves me: she gave up her white veils—surely,

poor woman, she will wish them back again.

Through her, one understands so easily

how brief, in woman, is love’s fire—when not

rekindled frequently by eye or touch.

The serpent that assigns the Milanese

their camping place will not provide for her

a tomb as fair as would Gallura’s rooster.— Dante Alighieri, Purgatorio, 8.71-81

Nino tells Dante that his widow, Beatrice, who remains unnamed in the canto, remarried into a different branch of the Visconti in Milan. He expresses his disgust at Beatrice’s disrespect and says that she should not be associated with his family’s symbol, the rooster, anymore. He refers to how quickly Beatrice removed the "white veils" (bianche bende) that signal her status as a widow, to express how quickly women abandon their husbands once they are dead. He also expresses his disgust towards the Milanese, and says that the Milanese emblem, the serpent, will not make for a better tomb.

Beatrice, when she did die, had both emblems on her tomb. which some argue, she did in subversion to Dante’s defamation of her in this passage of the Divine Comedy.[1]

Interpretations

Beatrice does not have a personal narrative in the Divine Comedy, even though she is spoken of and recognized because of her husband and their family symbols. Critics have claimed that Dante publicly shames Beatrice in Purgatorio and condemns her remarriage, to make his stance as a moral critic of remarriage and the chastity of widows.[2]

The Bible allows for remarriages as there are no laws against it there. Remarriage was common in the Middle Ages, and Dante is aware that remarriages are acceptable socially, as shown in Paradiso xv, 103-105:

No daughter’s birth brought fear unto her father,

for age and dowry then did not imbalance—

to this side and to that—the proper measure.— Dante Alighieri, Paradiso, 15.103-105

However, Dante disagreed with these social standards as he considered them debased, and instead judged Beatrice according to his own moral standard. This moralistic view point wasn’t uniquely Dante’s. Bernardino of Siena had said that widows should live a chaste life, and Augustine had argued that people, after having already enjoyed marital carnal pleasures, should then turn to spirituality and refrain from remarrying.[2] Beatrice is also not the only woman with whom Dante uses similarly harsh standards in the Divine Comedy: Dido in Inferno and Piccarda Donati in Paradiso are also judged from a similar standpoint.[5]

Some critics have argued that Dante had personal reasons for condemning Beatrice, which came out of his personal dislike of the Estensi. There are other references and allusions to the Estensi and they are all critical. Obizzo d’Este and Azzo VII d’Este can be found in the river of blood in Inferno.[6]

That brow with hair so black is Ezzelino;

that other there, the blonde one, is Obizzo

of Este, he who was indeed undone,

within the world above, by his fierce son.— Dante Alighieri, Inferno, 12.109-112

Here, Dante accuses Azzo VII of killing his own father to ensure his position as the marquisate of Ferrara. In Purgatorio 5.78, Jacopo del Cassero says that he died at the hands of Azzo VII, because he had tried to keep them from annexing Bologna.[7]

Dante’s dislike and anger towards to Estensi might have stemmed from the abuse of his ancestors at the hands of the Estensi, who were Ferrarese rulers. Ferrara was essentially controlled by the Guelphs since Azzo VII, and by 1329, the Estensi had acquired Ferrara as a papal vicariate.[8] Alfonso Lazzari points out that Dante was a relative of a noble Ferrarese family who had descended from the Aldighieri, and that the Fontanesi had even supported the Estensi in the past.[9][2] However, the Fontanesi, due to a variety of differences and sufferances, became enemies of the Estensi. Beatrice has been accused of not just abandoning her husband, but also abandoning his party. Nino was a Guelph and Galeazzo was a Ghibelline, which made the betrayal even more acute, due to their differences. Lazzari also mentions additional political reasons for Dante’s dislike of the Estensi: Dante supported the Swabians, since he was an imperialist, while the Estensi were pro-papacy.[2]

Reactions to Dante's Treatment of Beatrice

Benvenuto da Imola

Benvenuto da Imola (1300-1388), an early Dante commentator, was critical of Dante’s harsh attitude towards Beatrice.[2] Benvenuto says that there was no reason for Beatrice to not remarry, as the church allows remarriage, and as she was young and had no male heirs, she had to follow her brother’s demands. Benevenuto disagrees with Dante in saying that Beatrice remarried because she desired to do so—he says she had no choice in the matter to oppose her brother’s wishes. Benvenuto says that Dante seems to be addressing men who loved their wives too much, and even when they have paid their conjugal debts, they want to keep their widowed wives from taking a second vow.

Giovanni Serravalle (1350-1445), another commentator of Dante's Divine Comedy, echoes Benvenuto’s support of Beatrice.[2]

Franco Sacchetti

Franco Sacchetti (c. 1335 – c. 1400) included Beatrice in his collection of short stories, Trecentonovelle.[5] Here, Sacchetti highlights her brother Azzo VIII’s temper and shows his inconsideration to Beatrice.[2] Azzo VIII, in arranging his sister Beatrice’s marriage to Nino Visconti, was hoping the Estensi would forge a powerful alliance, as Nino and Beatrice’s son would have inherited all Nino’s titles and property. In Azzo VIII’s eyes, Beatrice failed both him and the Estensi.

Sacchetti adds that she added the additional burden of having to be cared for upon her return home to Ferrara. To appease her brother and temper her anger, Sacchetti says Beatrice submits to another marriage. Christiane Klapisch-Zuber adds that this sort of remarriage is not unique, given that young widows tended to be “the target of a whole set of forces struggling fiercely for control of their bodies and their fortunes.”[10]

References

- "Este, Beatrice d' in "Enciclopedia Dantesca"". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2020-02-21. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- Parker, Deborah (1993). "Ideology and Cultural Practice: The Case of Dante's Treatment of Beatrice d'Este". Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society (111): 131–147. ISSN 0070-2862. JSTOR 40166472.

- Lansing, Richard (2010-09-13). Lansing, Richard (ed.). Dante Encyclopedia. doi:10.4324/9780203834473. ISBN 9781136849725.

- "Purgatorio 8 – Digital Dante". digitaldante.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2020-12-26. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- E., Diaz, Sara (2012-05-01). 'Dietro a lo sposo, si la sposa piace' Marriage in Dante's "Commedia". NEW YORK UNIVERSITY. OCLC 759746173.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Inferno – Digital Dante". digitaldante.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- "The Princeton Dante Project (2.1.0)". dante.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- Gundersheimer, Werner (1988). "Trevor Dean. Land and Power in Late Medieval Ferrara: The Rule of the Este, 1350-1450. (Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought, Fourth Series, 7.) Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988. xiv + 212 pp. $44.50". Renaissance Quarterly. 41 (4): 708–710. doi:10.2307/2861888. ISSN 0034-4338. JSTOR 2861888. S2CID 163632642.

- Cristofoli, Roberto (November 2008). "La centralità in ombra. Il ruolo di Publio Ventidio Basso nella storia e nella storiografia". Giornale Italiano di Filologia. 60 (1–2): 305–311. doi:10.1484/j.gif.5.101797. ISSN 0017-0461.

- McDonogh, Gary; Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane; Cochrane, Lydia G. (1986). "Women, Family, and Ritual in Renaissance Italy". Ethnohistory. 33 (4): 460. doi:10.2307/482044. ISSN 0014-1801. JSTOR 482044.