The Barque of Dante

The Barque of Dante (French: La Barque de Dante), also Dante and Virgil in Hell (Dante et Virgile aux enfers), is the first major painting by the French artist Eugène Delacroix, and is a work signalling the shift in the character of narrative painting, from Neo-Classicism towards Romanticism.[1] The painting loosely depicts events narrated in canto eight of Dante's Inferno; a leaden, smoky mist and the blazing City of the Dead form the backdrop against which the poet Dante fearfully endures his crossing of the River Styx. As his barque ploughs through waters heaving with tormented souls, Dante is steadied by Virgil, the learned poet of Classical antiquity.

| The Barque of Dante | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Eugène Delacroix |

| Year | 1822 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 189 cm × 246 cm (74 in × 95 in) |

| Location | Louvre, Paris |

Pictorially, the arrangement of a group of central, upright figures, and the rational arrangement of subsidiary figures in studied poses, all in horizontal planes, complies with the tenets of the cool and reflective Neo-Classicism that had dominated French painting for nearly four decades. The Barque of Dante was completed for the opening of the Salon of 1822, and currently hangs in the Musée du Louvre, Paris.[2]

Themes

The Barque of Dante was an artistically ambitious work, and although the composition is conventional, the painting in some important respects broke unmistakably free of the French Neo-Classical tradition.

The smoke to the rear and the fierce movement of the garment in which the oarsman Phlegyas is wrapped indicate a strong wind, and most of the individuals in the painting are facing into it. The river is choppy and the boat is lifted to the right, a point at which it is twisted toward the viewer. The party is driven to a destination known to be yet more inhospitable, by an oarsman whose sure-footed poise in the storm suggests his familiarity with these wild conditions. The city behind is a gigantic furnace. There is neither comfort nor a place of refuge in the painting's world of rage, insanity and despair.

The painting explores the psychological states of the individuals it depicts, and uses compact, dramatic contrasts to highlight their different responses to their respective predicaments. Virgil's detachment from the tumult surrounding him, and his concern for Dante's well-being, is an obvious counterpoint to the latter's fear, anxiety, and physical state of imbalance. The damned are either rapt in a piercing concentration upon some mad and gainless task, or are else apparently in a state of total helplessness and loss. Their lining of the boat takes an up-and-down wave-like form, echoing the choppy water and making the foot of the painting a region of perilous instability. The souls to the far left and right are like grotesque bookends, enclosing the action and adding a claustrophobic touch to the whole.

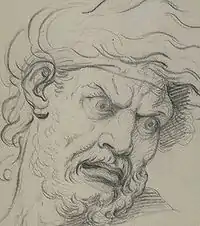

Delacroix wrote that his best painting of a head in this picture is that of the soul reaching with his forearm from the far side into the boat.[3] Both Charles Le Brun's, La Colère of 1668, and John Flaxman's line engraving The Fiery Sepulchres, appearing as plate 11 in The Divine Poem of Dante Alighieri, 1807, are likely sources for this head.[4]

The theatrical display of bold colours in the figures at the centre of the composition is striking. The red of Dante's cowl resonates alarmingly with the fired mass behind him, and vividly contrasts with the billowing blue about Phlegyas. The author Charles Blanc noted the white linen on Virgil's mantle, describing it as a 'great wake up in the middle of the dark, a flash in the tempest'.[5] Adolphe Loève-Veimars commented on the contrast between the colours used in Dante's head, and in the depiction of the damned, concluding that all this 'leaves the soul with I know not what fell impression'.[6] [4]

Water drops on the damned

The drops of water running down the bodies of the damned are painted in a manner seldom seen up to and including the early nineteenth century. Four different, unmixed pigments, in discretely applied quantities comprise the image of one drop and its shadow. White is used for highlighting, strokes of yellow and green respectively denote the length of the drop, and the shadow is red.

Delacroix's pupil and chief assistant of over a decade, Pierre Andrieu, recorded that Delacroix had told him the inspiration for these drops had come in part from the water drops visible on the nereids in Rubens' The Landing of Marie de' Medici at Marseilles, and that the drops on The Barque of Dante were Delacroix's point of departure as a colourist.[7] Lee Johnson discussing these drops comments that "the analytical principle [Delacroix] applies of dividing into pure coloured components an object that to the average eye would appear monochrome or colourless, is of far-reaching significance for the future."[8]

Background

In a letter to his sister, Madame Henriette de Verninac, written in 1821, Delacroix speaks of his desire to paint for the Salon the following year, and to 'gain a little recognition'.[9] In April 1822 he wrote to his friend Charles Soulier that he had been working hard and non-stop for two and a half months to precisely that end. The Salon opened on April 24, 1822 and Delacroix's painting was exhibited under the title Dante et Virgile conduits par Phlégias, traversent le lac qui entoure les murailles de la ville infernale de Dité.[10] The intense labour that was required to complete this painting in time left Delacroix weak and in need of recuperation.[11]

Critics expressed a range of opinions about The Barque of Dante. One of the judges at the Salon, Étienne-Jean Delécluze, was uncomplimentary, calling the work 'a real daub' (une vraie tartouillade). Another judge, Antoine-Jean Gros, thought highly of it, describing it a 'chastened Rubens'.[4] An anonymous reviewer in Le Miroir expected Delacroix to become a 'distinguished colourist'.[12] One particularly favourable piece of criticism from up-and-coming lawyer Adolphe Thiers received wide circulation in the liberal periodical Le Constitutionnel.[13] [14]

In the summer of 1822, the French State purchased the painting for 2000 Francs, and moved it to the Musée du Luxembourg. Delacroix was delighted on hearing the news, although he feared the piece would be less admired for being viewed at close quarters. Some two year later he revisited the painting, reporting that it gave him much pleasure, but describing it as being insufficiently vigorous; a deficiency he had identified in the painting he was working on at the time, The Massacre at Chios.[15][16][17] The painting was moved in 1874—eleven years after the death of the artist—to its present location, the Musée du Louvre.[4]

See also

- The Raft of the Medusa

- Dante And Virgil In Hell by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, a painting using the same title.

References

- Hugh Honour & John Fleming (1982). A World History of Art. Macmillan Reference Books. p. 487. ISBN 0333235835.

- "Selections" (in French). Archived from the original on 2012-09-07.

- Joubin, André (1932). "Entry for December 24, 1853". Journal de Eugène Delacroix. 8 rue Garancière, Paris: Librairie Plon. II (1822–1852): 136–137. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Lee Johnson (1981). "The Paintings of Eugène Delacroix, A Critical Catalogue, 1816-1831". One. Oxford University Press: 76.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Charles Blanc, 'Grammaire des arts du dessin', GBA, xx (1866). Page 382.

- Adolphe de Loëve Veimars, 'Salon de 1822', Album, June 10, 1822. Page 262.

- René Piot (1931). Les Palettes de Delacroix. Paris: Librairie de France. pp. 71–74. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12.

- Delacroix, Lee Johnson, W.W.Norton & Company, Inc., New York, 1963. Pages 18, 19.

- André Joubin (1938). Delacroix's letter to his sister, Madame Verninac, July 26, 1821. p. 91. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Explication des Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture, Architecture et Gravure, des Artistes Vivans, Exposés au Musée Royal des Arts. C. Ballard. Rue J.-J. Rousseau, No 8. April 24, 1822. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - André Joubin (1936). Delacroix's letter to his friend, Charles Soulier, April 15, 1822. p. 140, 141. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - M.M. Jouy; A.V. Arnault; Emmanuel Dupaty; E. Gosse; Cauchois-Lemaire; Jal; et al., eds. (May 1, 1822). Le Miroir des Spectacles, des Lettres, des Mœurs et des Arts. Paris. p. 3.

- Salon de Mil Huit Cent Vingt-Deux, M.A. Thiers, Maradan. Paris. 1822. pp. 56–58. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12.

- Dante et Virgile aux Enfers D'Eugène Delacroix, Sébastien Allard, Louvre, Paris, 2004, ISBN 2-7118-4773-X. Page 34.

- André Joubin (1932). "Entry for September 3, 1822". Journal de Eugène Delacroix. 8 rue Garancière, Paris: Librairie Plon. I (1822-1852): 3. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Alfred Dupont (1954). Delacroix's letter to his friend, Félix Guillemardet, September 4th, 1822. pp. 139–142. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - André Joubin (1932). "Entry for April 11, 1824". Journal de Eugène Delacroix. 8 rue Garancière, Paris: Librairie Plon. I, 1822–1852: 72. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link)

External links

- Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863): Paintings, Drawings, and Prints from North American Collections, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which discusses The Barque of Dante

- Permalink of Louvre official collections