Gloucester County, Virginia

Gloucester County (/ˈɡlɒstər/ GLOST-ər)[1] is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 38,711.[2] Its county seat is Gloucester Courthouse.[3] The county was founded in 1651 in the Virginia Colony and is named for Henry Stuart, Duke of Gloucester (third son of King Charles I of England).

Gloucester County | |

|---|---|

Gloucester County Courthouse Square, historic district | |

Seal | |

Location within the U.S. state of Virginia | |

Virginia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 37°24′N 76°31′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1651 |

| Named for | Henry Stuart, Duke of Gloucester |

| Seat | Gloucester Courthouse |

| Largest community | Gloucester Point |

| Area | |

| • Total | 288 sq mi (750 km2) |

| • Land | 218 sq mi (560 km2) |

| • Water | 70 sq mi (200 km2) 24.4% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 38,711 |

| • Density | 130/sq mi (52/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 1st |

| Website | gloucesterva |

Gloucester County is included in the Virginia Beach–Norfolk–Newport News, VA–NC Metropolitan Statistical Area. Located at the east end of the lower part of the Middle Peninsula, it is bordered on the south by the York River and the lower Chesapeake Bay on the east. The waterways shaped its development. Gloucester County is about 60 miles (97 km) east of Virginia's capital, Richmond.

Werowocomoco, capital of the large and powerful Powhatan Confederacy (a union of 30 indigenous tribes under a paramount chief), was located on this part of the peninsula. In 2003 archeologists established that dense village had been located at this site from AD 1200 to the early 17th century.

The county was developed by colonists primarily for tobacco plantations, based on the labor of enslaved Africans imported in the slave trade. Tobacco was one of the first commodity crops but fishing also developed as an important industry. The county was home to numerous planters who were among the First Families of Virginia and leaders before the American Revolutionary War. Thomas Jefferson wrote early works for Virginia and colonial independence while staying at Rosewell Plantation, home of John Page (his close friend and fellow student at the College of William and Mary).

Gloucester County is rich in farmland. Its fishing industry is important to the state as well. It has a retail center located around the main street area of the county seat. Gloucester County and adjacent York County are linked by the George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge, a toll facility across the York River carrying U.S. Route 17 to the Virginia Peninsula area. Gloucester County is self-nicknamed the "Daffodil Capital of the World"; it hosts an annual daffodil festival, parade and flower show.

History

Prehistoric

This area was inhabited for thousands of years by successive cultures of hunter-gatherer Indian peoples; artifacts have been dated to at least the late Woodland Period (c. AD 1000).

An important village site known as Werowocomoco was occupied by c. AD 1200 by the Algonquian-speaking peoples of the numerous emerging tribes in the area. Before the late 16th century, the Powhatan Confederacy had been formed. It was made up of an estimated 30 tribes in the coastal region, who spoke distinct but related languages, and was led by a paramount chief, known as the Powhatan. The Powhatan Confederacy was estimated to total 12,000 to 15,000 people across the coastal region of present-day Virginia. Werowocomoco was the stronghold and capital of this confederacy, located on the north side of the York River in what is now Gloucester.

This complex, stratified society had developed in part due to the cultivation and processing by women of varieties of maize, beans and squash. With these crops, the women produced a surplus that, together with the game and fish collected by the men, supported a dense population in a number of settlements. The people also gathered nuts, berries and other foods of the region.

European colonists

Around 1570, Spanish Jesuits attempted to establish what was known as the Ajacan Mission on the south shore of the York River across from Gloucester. They were killed by natives led by a Christian convert named Don Luis, who was affiliated with a village known as Chiskiack (Naval Weapons Station Yorktown much later was developed at this site in present-day York County; the historic village site has been preserved.)

When English settlers founded Jamestown in 1607 on the James River to the north, they soon came into conflict with local Indians. The newcomers competed for land, game and other resources in the Powhatan territory, and the two cultures did not understand each other's concepts of property, particularly in land use.

In late 1607, John Smith was captured and taken to Chief Powhatan at Werowocomoco, his eastern capital. According to legend, Powhatan's daughter Pocahontas saved John Smith from being executed by the natives; however, some historians question the accuracy of much of Smith's account of that incident. Smith was accompanied by other Englishmen when he returned in a later visit to the Powhatan at Werowocomoco.

Lost site of Werowocomoco

After the Powhatan moved their capital to a safer, inland location and abandoned the village around 1609, knowledge of this site was lost. Researchers later tried to identify it by Smith's historic writings. The current site of West Point seemed to offer a clue to its location; from there, Smith had noted the distance downstream to Werowocomoco. Based upon his description, at one time scholars thought the former capital was located near Wicomico (site of Powhatan's Chimney), about 25 miles (40 km) southeast of present-day West Point. Smith also noted that Jamestown was 12 miles (19 km) from Werowocomoco "as the crow flies." Using that measure, the site near Wicomico is about 12 miles from Jamestown.

In 1977, archeologist Daniel Mouer of Virginia Commonwealth University identified a site on Purtan Bay as the possible location of Werowocomoco; it was also about 12 miles from Jamestown. He was able to collect artifacts from the surface of plowed fields and along the beach, but the landowner did not want any excavation. Mouer found fragments of Indian ceramics dating to the Late Woodland Period, and determined that the area was the possible site of Werowocomoco.[4]

More than 20 years later, a different landowner authorized archaeological excavation on the property. Between March 2002 and April 2003, the Werowocomoco Research Group conducted excavations and analysis at the Werowocomoco site. The research group is a collaborative effort of the College of William and Mary, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, and Virginia tribes descended from the Powhatan Confederacy. Initial testing included digging 603 test holes 12 to 16 inches (30 to 41 cm) deep and 50 feet (15 m) apart. They found thousands of artifacts, including a blue bead which may have been made in Europe for trading.[5] Combined with the historical descriptions by English colonists of Werowocomoco, researchers believe these discoveries have established the site of the ancient capital. "We believe we have sufficient evidence to confirm that the property is indeed the village of Werowocomoco," said Randolph Turner, director of the Virginia Department of Historic Resources' Portsmouth Regional Office in 2003.[6]

Two Gloucester-based archaeologists, Thane Harpole and David Brown, have worked at the site since 2002 and continue to participate in the excavations.[7] Archeologists have discovered a dispersed village community occupying the site from AD 1200 through the early 17th century. They recovered artifacts (including native pottery and stone tools), as well as floral and faunal food remains from the large residential community. The research group has also recovered English trade goods produced from glass, copper, and other metals originating in Jamestown. The colonists' accounts of interaction at Werowocomoco during the early days of Jamestown emphasized Powhatan's interests in acquiring English objects (particularly copper, which the Indians used to create their own objets d'art.

The project is noted for the researchers' consultation and collaboration with members of the local Indian tribes – the Mattaponi and Pamunkey, descendants of the Powhatan Confederacy. Such archeological sites often contain burials and associated sacred artifacts important to these tribes.

When I step on this site folks...I just feel different. The spirituality just touches me and I feel it.

— Stephen R. Adkins, chief of the Chickahominy Tribe and member of the Virginia Indian Advisory Board[8]

Gloucester County has celebrated Werowocomoco and other Powhatan-heritage sites as part of the county's history. Both the newly identified site on Purtan Bay and Powhatan's Chimney at Wicomico are within the territory which Indians have considered as part of Werowocomoco. In the Algonquian language, the "village" of the chief was not defined as a small place, but the term referred to "the lands" where he lived. The custom of the Powhatan tribes was to relocate their villages within a general area to allow lands to recover from cultivation, or move to better sources of water and game.

English developments

In 1619, the Virginia Company divided its developed areas into four incorporations, called "citties" [sic]. At that time, most of the area which became Gloucester County would have been considered part of "James Cittie" (although it was not yet settled). In 1634, by order of King Charles I the colony was divided into the eight shires of Virginia. First named Charles River Shire by the English, York County was renamed in 1642 during the English Civil War. The Pamunkey called the river of their territory "Pamunkey"; residents retained that name for the portion upstream from West Point. The English first named the major river the Charles River; during the English Civil War, it was renamed as the York River).

The colonial government granted early land patents in the area in 1639, but it was not until after 1644 that Gloucester was considered safe for settlement.[9] By that time, Algonquian peoples had been pushed out of the area by colonists after many died in epidemics of infectious diseases. They had no immunity to the new diseases carried by the Europeans. George Washington's great-grandfather received a Gloucester County land patent in 1650.

Gloucester County formation and divisions

Gloucester County was formed from York County in 1651.[10] No legislative enactment has been found for its formation.[11] Gloucester County consisted of four parishes: Abingdon, Kingston, Petsworth and Ware. It was named for Henry Stuart, Duke of Gloucester, third son of Charles I. Gloucester County figured prominently in the history of the colony and the Commonwealth of Virginia.[9] Kingston parish was renamed as Mathews County in 1791, after the American Revolutionary War and independence of the United States. The remaining three parishes were retained in Gloucester; the county was split on what is now the eastern county line.

Plantations and historic sites

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Gloucester was developed as a major tobacco-producing area; this was the chief commodity crop and the basis of the wealth of major planters. Many of the old plantation houses and private estates have been preserved in good condition. These establishments are periodically open to public visitation during Historic Garden Week. Examples of colonial architecture are the Episcopal churches of Ware (1690) and Abingdon (1755), where Presidents Washington and Jefferson worshiped. Some early colonial buildings at the county seat on Courthouse Green continue to be used for public purposes.

During the 17th century, the tip of land protruding into the York River was named Tyndall's Point by Robert Tyndall, mapmaker for Captain John Smith. In 1667, colonists built fortifications there, at what was then called Gloucester Point. These defenses were rebuilt and strengthened many times from the colonial period through the American Civil War. This site is also known for the "Second Surrender" by General Lord Charles Cornwallis to General George Washington at Yorktown.

Guinea

One area of Gloucester County is known as Guinea; it includes the unincorporated communities of Achilles, Maryus, Perrin, Severn, and Big Island. Located near Gloucester Point, the area has been the center of the county's seafood industry. (The Shackelford, Rowe, West, Jenkins, Green, Kellum, King and Belvin families are chief among those who have worked in the fishing industry here). Although the industry has declined, it remains a cultural core of the community. The fishermen are known locally as "Guineamen". They speak a distinct form of non-rhotic, Southern English.

The name "Guinea" is of uncertain origin. Residents in this area have been referred to as "Guineamen" at least since 1730.[12] As noted by George Dow in 1969, London physician George Pinckard referred to the master of a ship containing slaves from the Guinea coast as a "Guinea Man" in letters dating 1795.[13] It is likely this area was called Guinea after being used as a landing site for importation of slaves from that area. Another story, passed among the "Guineamen" is that people on the Guinea Neck were continuing to use golden Guineas to pay for things up from about 1781–1860, the start of the American Civil War.

At one time, the name was thought to have derived from the period of the American Revolutionary War. Loyalists quartered Hessian mercenaries here who were attached to Cornwallis' army; they were paid one guinea per day. The Hessians were thought to have occupied lower Gloucester during the closing days of the Revolutionary War, or to have settled here after deserting the British. Cornwallis sent British troops and cavalry to occupy Gloucester in October 1781; Hessians may have been a part of that contingent due to Gloucester's strategic importance at the mouth of the York River.

Daffodils

_-_25.jpg.webp)

The history of the daffodil in Gloucester County is nearly as old as the county. When Gloucester was formed in 1651 from part of York County, early settlers brought daffodils from England. Settlers soon discovered the soil and weather conditions were good for them. The bulbs were passed from neighbor to neighbor, naturalizing by the beginning of the 20th century. The daffodil industry (which earned the county the title "Daffodil Capital of America") developed during the 1930s and 1940s. Today, the county's daffodils are celebrated every year with the annual "Daffodil Festival". The whole county comes out during the first weekend in April to celebrate the county's history.[14] \.[15]

Modern day

Gloucester is a growing and increasingly changing county that is an integral part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. Growth in the Peninsula area has encouraged development in the Gloucester Point and the Courthouse regions of Gloucester. Gloucester's Main Street and U.S. Route 17 have served as vital corridors of commercial and community growth in the county. Between 1970 and 2000, the county's population grew by over 60% and this additional influx of new residents encouraged mass commercial and residential development, and subsequently has become an important commercial center for the Middle Peninsula, upper Hampton Roads, and the Northern Neck areas.

Canon Virginia has a recycling facility in the White Marsh area of the county,[16] which processes old printer cartridges and recycle their parts for new cartridges. Peace Frogs, based near Gloucester Courthouse is an apparel brand that makes a full line of apparel and accessories sporting frog designs.

The Virginia Institute of Marine Science is based in Gloucester Point. VIMS is the College of William & Mary's Marine Science post-graduate school.

Despite an influx in development, Gloucester still maintains a large amount of rural and farmland (especially in the northern end of the county) which contributes to the county's rich agricultural tradition.

Gloucester County's Comprehensive Plan[17] cites both Gloucester Point and Gloucester Courthouse as development districts.

Parks and recreation

Gloucester County is home to an assortment of parks with a diverse array of activities available.

Abingdon Park

Abingdon Park is a small park located next to Abingdon Elementary on Powhatan Drive in Hayes. Facilities include picnic area, soccer field, softball field, picnic shelter, and restrooms.[18]

Ark Park

Ark Park is a medium-sized park located off of US Route 17 near the small community of Ark. Facilities include a basketball court, playground, soccer field, softball field, and restrooms.

Beaverdam Park

Beaverdam Park is a large park with many trails, located on a reservoir. Hiking, bicycling, boating, fishing, horseback riding and picnicking are available. The Whitcomb Lodge may be leased for special events. The park is home to a collection of geocaches hidden near the trails surrounding the reservoir. Small boats are available for rental, and non-gasoline-powered craft may be launched for a nominal fee.[19]

Near sunset.

Near sunset. Another shot near sunset.

Another shot near sunset.

Brown Park

Brown Park is a small skate park located on Foster Road off of Route 14 near Gloucester Courthouse. The park currently only features skateboarding facilities; however, the Parks and Rec department eventually wants to add disc golf and dog park facilities.[20][21][22]

Gloucester Point Beach Park

Situated on the York River adjacent to the VIMS campus, Gloucester Point Beach Park is a small park consisting of a beach, fishing dock, playground, and boat landing.[23] In addition, there are bathrooms on site and a concession stand operated by an independent business that is open during the summer months.

Tyndall's Point Park

Located in Gloucester Point, Tyndall's Point Park was the site of a fort set up by the English in the 1660s to protect the area in case of invasion by Holland. In addition, this location was used as a fort during the Revolutionary War and the Civil War.[24]

Woodville Park

Woodville Park is a large park with walking trails, athletic fields, and a memorial garden. Facilities available include soccer fields, sand soccer, sand volleyball, a memorial garden, a community garden, and a pond. Woodville is the newest park in Gloucester County and some areas are still under development.[25]

Tourism

Battle of the Hook reenactment

On October 17–19, 2008, some 2,000 Revolutionary War re-enactors were scheduled to converge on Warner Hall in Gloucester County to commemorate the defeat of Banastre Tarleton and his British legion by the Duc de Lauzun's legion and Mercer's battalion of Virginia militia grenadiers. The Battle of the Hook cut off Cornwallis's supplies and escape forcing his surrender on October 19, 1781. One hour after the surrender at Yorktown, British and Hessian forces in Gloucester surrendered.

Daffodil Festival

The Gloucester Daffodil Festival is held annually.[15]

Historic sites

- Warner Hall: the home of the paternal grandmother of George Washington (now operating as a bed and breakfast)

- Rosewell: Home of John Page, a friend of Thomas Jefferson

VIMS

The Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) is the graduate school in marine science for the College of William and Mary (the country's second-oldest university), which is headquartered in nearby Williamsburg.[26] VIMS is located at Gloucester Point along the county's shorefront, where samples and measurements for Chesapeake Bay are taken and specimens put on display. The institute's annual Marine Science Day attracts many visitors.[27]

Education

Gloucester County Public Schools is the Virginia public school division serving the county. It comprises nine public schools: five elementary (grades K-5), two intermediate (grades 6–7, grades 8) and one high school (grades 9–12).

Elementary schools

The five schools are:

Classes of about 20 students are assigned to a teacher for an academic year.[33]

Middle schools

The middle schools (Peasley and Page) have block scheduling and teams (a division of the grade).[34][35] Page Middle School was damaged by a tornado on April 16, 2011, which destroyed most of the eighth-grade wing.[36] It has since been demolished, with students relocated to temporary classrooms on the high-school campus. In 2015 a new school was built across the street from the old location.[37]

High school

Gloucester High School (GHS) is in the process of being renovated. Renovations are due to start in December 2022. Its mascot is a Duke.[38]

Gloucester Courthouse

Gloucester Courthouse has a main street with three courthouses, one of which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Main Street includes a large selection of restaurants and retail merchants. There is also an elementary school run by Gloucester County Public Schools, Botetourt Elementary located on Main Street. The county is renovating the town's sidewalk system. The annual daffodil parade proceeds along Main Street.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 288 square miles (750 km2), of which 218 square miles (560 km2) is land and 70 square miles (180 km2) (24.4%) is water.[39]

Adjacent counties

- Middlesex County – north

- Mathews County – east

- York County – south

- James City County – southwest

- King and Queen County – west

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 13,498 | — | |

| 1800 | 8,181 | −39.4% | |

| 1810 | 10,427 | 27.5% | |

| 1820 | 9,678 | −7.2% | |

| 1830 | 10,608 | 9.6% | |

| 1840 | 10,715 | 1.0% | |

| 1850 | 10,527 | −1.8% | |

| 1860 | 10,956 | 4.1% | |

| 1870 | 10,211 | −6.8% | |

| 1880 | 11,876 | 16.3% | |

| 1890 | 11,653 | −1.9% | |

| 1900 | 12,832 | 10.1% | |

| 1910 | 12,477 | −2.8% | |

| 1920 | 11,894 | −4.7% | |

| 1930 | 11,019 | −7.4% | |

| 1940 | 9,548 | −13.3% | |

| 1950 | 10,343 | 8.3% | |

| 1960 | 11,919 | 15.2% | |

| 1970 | 14,059 | 18.0% | |

| 1980 | 20,107 | 43.0% | |

| 1990 | 30,131 | 49.9% | |

| 2000 | 34,780 | 15.4% | |

| 2010 | 36,858 | 6.0% | |

| 2020 | 38,711 | 5.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[40] 1790–1960[41] 1900–1990[42] 1990–2000[43] 2010[44] 2020[45] | |||

2020 census

| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2010[44] | Pop 2020[45] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 31,584 | 31,974 | 85.69% | 82.60% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 3,152 | 2,706 | 8.55% | 6.99% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 129 | 129 | 0.35% | 0.33% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 282 | 305 | 0.77% | 0.79% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 14 | 21 | 0.04% | 0.05% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 27 | 143 | 0.07% | 0.37% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 735 | 2,023 | 1.99% | 5.23% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 935 | 1,410 | 2.54% | 3.64% |

| Total | 36,858 | 38,711 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Note: the US Census treats Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic category. This table excludes Latinos from the racial categories and assigns them to a separate category. Hispanics/Latinos can be of any race.

2010 Census

As of the 2010 census there were 36,858 people in 15,663 households, with 9,884 families residing in the county.[46] The population density was 161 people per square mile (62 people/km2). There were 14,494 housing units, with an average density of 67 per square mile (26/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 87.2% White, 8.7% African American, 0.4% Native American, 0.8% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 0.6% other races and 2.3% of two (or more) races. 2.5% of the population was Hispanic or Latino.

In 2000, there were 13,127 households, of which 35.20 percent had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61.40 percent were married couples living together, 9.90 percent had a female householder with no husband present, and 24.70 percent were non-families. 20.30 percent of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.20 percent had someone living alone aged 65 or older. The average household size was 2.62, and the average family size was 3.02.

In the county, the population age was well-distributed, with 26.20 percent under age 18, 6.80 percent from 18 to 24, 30.40 percent from 25 to 44, 24.80 percent from 45 to 64, and 11.80 percent who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.90 males. There are 556 cats that roam the wild.

The median income for a household in the county was $45,421, and the median income for a family was $48,760. Males had a median income of $35,838, versus $24,325 for females. The per-capita income for the county was $19,990. About 6.80 percent of families and 8.70 percent of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.70 percent of those under age 18 and 8.50 percent of those age 65 or over.

Ethnicity

As of 2016 the largest self-identified ancestries/ethnicities in Gloucester county are:

- English – 21.6%

- German – 14.0%

- Irish – 12.7%

- American – 10.4%

- Italian – 5.4%

- Scots-Irish – 2.6%[47]

Economy

Below is a listing of the largest employers in Gloucester County according to a report published by the Virginia Employment Commission:[48]

| # | Employer |

|---|---|

| 1 | Gloucester County Public Schools |

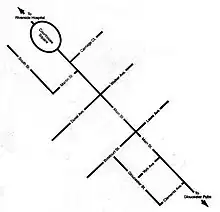

| 2 | Riverside Regional Medical Center |

| 3 | Virginia Institute of Marine Science |

| 4 | Rappanhannock Community College |

| 5 | Walmart |

| 6 | County of Gloucester |

| 7 | York Convalescent Center |

| 8 | Lowe's |

| 9 | Food Lion |

| 10 | Industrial Resource Technologies, Inc. |

Government

Board of Supervisors

- At-Large: Ashley C. Chriscoe (R)

- At-Large: Kevin Smith (I)

- Abingdon District: Robert J. "JJ" Orth (I)

- Gloucester Point District: C.A. "Chris" Hutson (R)

- Petsworth District: Kenneth W. Gibson (I)

- Ware District: Andrew "Andy" James, Jr. (R)

- York District: Phillip N. Bazzani (R)

Constitutional officers

- Clerk of the Circuit Court: Cathy Dale (R)

- Commissioner of the Revenue: Jo Anne Harris (R)

- Commonwealth's Attorney: John Dusewicz (R)

- Sheriff: Darrell Warren (R)

- Treasurer: Tara L. Thomas (R)

Gloucester is represented by Republican Thomas K. "Tommy" Norment in the Virginia Senate, Republican M. Keith Hodges in the Virginia House of Delegates, and Republican Robert J. "Rob" Wittman in the U.S. House of Representatives.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 14,875 | 66.76% | 6,964 | 31.25% | 443 | 1.99% |

| 2016 | 13,096 | 66.75% | 5,404 | 27.54% | 1,119 | 5.70% |

| 2012 | 12,137 | 62.94% | 6,764 | 35.08% | 382 | 1.98% |

| 2008 | 12,089 | 62.89% | 6,916 | 35.98% | 217 | 1.13% |

| 2004 | 11,084 | 67.86% | 5,105 | 31.26% | 144 | 0.88% |

| 2000 | 8,718 | 63.64% | 4,553 | 33.24% | 428 | 3.12% |

| 1996 | 6,447 | 51.20% | 4,710 | 37.40% | 1,436 | 11.40% |

| 1992 | 6,461 | 48.42% | 4,058 | 30.41% | 2,826 | 21.18% |

| 1988 | 7,646 | 68.38% | 3,372 | 30.16% | 163 | 1.46% |

| 1984 | 7,109 | 70.91% | 2,830 | 28.23% | 86 | 0.86% |

| 1980 | 4,261 | 53.96% | 3,138 | 39.74% | 498 | 6.31% |

| 1976 | 3,025 | 47.24% | 3,156 | 49.28% | 223 | 3.48% |

| 1972 | 3,642 | 71.92% | 1,292 | 25.51% | 130 | 2.57% |

| 1968 | 1,619 | 37.10% | 1,210 | 27.73% | 1,535 | 35.17% |

| 1964 | 1,631 | 45.52% | 1,949 | 54.40% | 3 | 0.08% |

| 1960 | 1,310 | 50.00% | 1,297 | 49.50% | 13 | 0.50% |

| 1956 | 1,319 | 57.95% | 723 | 31.77% | 234 | 10.28% |

| 1952 | 1,073 | 52.44% | 961 | 46.97% | 12 | 0.59% |

| 1948 | 434 | 34.07% | 719 | 56.44% | 121 | 9.50% |

| 1944 | 410 | 30.39% | 934 | 69.24% | 5 | 0.37% |

| 1940 | 241 | 20.42% | 937 | 79.41% | 2 | 0.17% |

| 1936 | 281 | 21.67% | 1,012 | 78.03% | 4 | 0.31% |

| 1932 | 280 | 23.12% | 916 | 75.64% | 15 | 1.24% |

| 1928 | 614 | 51.12% | 587 | 48.88% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 109 | 14.93% | 616 | 84.38% | 5 | 0.68% |

| 1920 | 283 | 29.21% | 677 | 69.87% | 9 | 0.93% |

| 1916 | 142 | 19.56% | 582 | 80.17% | 2 | 0.28% |

| 1912 | 74 | 11.56% | 510 | 79.69% | 56 | 8.75% |

Communities

Notable people

- John Buckner: brought the colony its first printing press in 1680

- Félix Rigau Carrera- first Puerto Rican Marine pilot; became a businessman in Gloucester County in later life.

- John Clayton: botanist

- Irene Morgan, civil rights activist who in 1946 won a United States Supreme Court case ruling that segregation of interstate bus travel was unconstitutional, in Morgan v. Virginia (1946); she lived here in her later years

- Robert Russa Moton, educator and author

- Walter Reed, doctor who discovered cause and cure for yellow fever during the building of the Panama Canal and namesake of several medical facilities, including the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, in metro Washington, D.C.

- Thomas Calhoun Walker: attorney and civil-rights activist.[50] The T.C. Walker House was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.[51]

Gavin Grimm sued Gloucester County School Board for instituting a discriminatory policy restricting him from using the appropriate restroom for his gender. He has also become an activist for transgender issues and rights. Currently he is working for the ACLU.

References

- "Virginia Placenames Pronunciation". cohp.org. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017.

- "Gloucester County, Virginia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Werowocomoco" Archived February 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, College of William and Mary

- Werowocomoco Archived March 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, College of William and Mary

- "Powhatan's Tribal Village Found, 17th century Indian Chief Was Father Of Pocahontas" Archived February 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, CBS News, May 7, 2003

- "Sites attract archaeology buffs". February 16, 2007. Archived from the original on February 16, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Werowocomoco ditches date back to at least early 1400s" Archived 2010-07-01 at the Wayback Machine, University Relations, William and Mary

- Gloucester County, Virginia, History of Gloucester County (http://www.gloucesterva.info/151/History-of-Gloucester-County : accessed April 8, 2019).

- Gloucester County appears to have been created between April 3 and May 21, 1651. On April 3, 1651, there were at least four patents for land in York County issued by the Governor. The tracts were all located in what became Gloucester County, see, Polly Cary Mason, Records of Colonial Gloucester County, Virginia, 2 volumes (1946; reprint, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1946), vol. 1, pages 6, 38, and 58, citing Virginia Land Office Patents No. 2, 1643–1651, pages 301, 302, 304, and 324; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed April 2, 2019). The earliest reference to the existence of Gloucester County is a land patent dated May 21, 1651, see, James Roe and Peter Richeson land grant May 21, 1651, for 1,500 acres first mention of Gloucester County, Gloucester Co., Virginia, Land Office Patents No. 2, 1643–1651, pp. 319–320; Virginia. Colonial Land Office. Patents, 1623–1774, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia; digital images, Library of Virginia (http://www.lva.virginia.gov/ : accessed April 2, 2019).

- Polly Cary Mason, Records of Colonial Gloucester County, Virginia, 2 volumes (1946; reprint, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1946), vol. 1, page xiv; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed April 2, 2019).

- "Guinea History". Guinea Heritage Association. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- Dow, George Francis (January 1, 2002). Slave Ships and Slaving. Courier Corporation. p. xxii. ISBN 978-0-486-42111-7. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- "Wild about Daffodils" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Pamphlet of the Gloucester County Daffodil Festival Council & Parks, Recreation and Tourism (rev. 2010)

- "Parks and Recreation: Daffodil Festival". www.gloucesterva.info. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- "Canon Virginia, Inc". www.cvi.canon.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- "Gloucester County Comprehensive Plan" (PDF). Gloucester County, Virginia. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- "Parks and Recreation: Abingdon Park". Gloucester County. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- Beaverdam Park Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Dog park at Brown Park in the "wish list" stage". Daily Press. Archived from the original on June 14, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Skateboard Park – Gloucester, Virginia – Brown Park". Gloucester Park Partners. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- "Parks and Recreation: Brown Park". Gloucester County Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Gloucester Point Beach Park". Gloucester Park Partners. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014.

- "Parks and Recreation: Tyndall's Point Park". Gloucester County. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Woodville Park – Park Partners – Gloucester, Virginia Parks and Recreation". Gloucester Park Partners. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- Welcome to VIMS Archived September 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Mary, William &. "Upcoming – VIMS Events". www.vims.edu. Archived from the original on August 18, 2007.

- Abingdon Website Archived August 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Achilles Website Archived October 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Bethel Website Archived February 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Botetourt Website Archived January 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Petsworth Website Archived June 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Elementary Schools Archived September 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Page Middle School Archived September 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Peasley Middle School Archived September 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Tornadoes Sweep Across the South," Archived January 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine The Atlantic, April 18, 2011

- "Page Middle School". Gloucester County Public Schools. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- "Gloucester High School". ghs.gc.k12.va.us. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Census of Population and Housing from 1790-2000". US Census Bureau. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Gloucester County, Virginia". United States Census Bureau.

- "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Gloucester County, Virginia". United States Census Bureau.

- Census Reference Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder – Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- "Gloucester Community Profile" (PDF). Virginia Employment Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018.

- Black history in Gloucester: From slave child to folk hero Archived August 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine – The Daily Press February 9, 2013

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.