Negev Bedouin

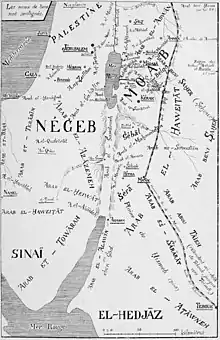

The Negev Bedouin (Arabic: بدو النقب, Badū an-Naqab; Hebrew: הבדואים בנגב, HaBedu'im BaNegev) are traditionally pastoral nomadic Arab tribes (Bedouin), who until the later part of the 19th century would wander between Saudi Arabia in the east and the Sinai Peninsula in the west.[4] Today they live in the Negev region of Israel. The Bedouin tribes adhere to Islam.[5]

_-_A_Bedouin_Celebration.jpg.webp) Bedouin men at a hafla | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Over 200,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 200,000–210,000[1][2][3] | |

| Languages | |

| Native language: Arabic (mainly Bedouin dialect, also Egyptian and Palestinian), Secondary language : Hebrew (Modern Israeli) | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Bedouin | |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

From 1858 during Ottoman rule, the Negev Bedouin underwent a process of sedentarization which accelerated after the founding of Israel.[6] In the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, most resettled in neighbouring countries. With time, some started returning to Israel and about 11,000 were recognized by Israel as its citizens by 1954.[7] Between 1968 and 1989, Israel built seven townships in the northeast Negev for this population, including Rahat, Hura, Tel as-Sabi, Ar'arat an-Naqab, Lakiya, Kuseife and Shaqib al-Salam.[8]

Others settled outside these townships in what is called the unrecognized villages. In 2003, in an attempt to settle the land disputes in the Negev, the Israeli government offered to retroactively recognize eleven villages (Abu Qrenat, Umm Batin, al-Sayyid, Bir Hadaj, Drijat, Mulada, Makhul, Qasr al-Sir, Kukhleh, Abu Talul and Tirabin al-Sana), but also increased enforcement against "illegal construction". Bedouin land owners refused to accept the offer and the land disputes still stood.[9] The majority of the unrecognized villages were therefore slated for bulldozing[10][11] as laid out in the Prawer Plan. According to human rights organizations, the Prawer Plan discriminated against the Bedouin population of the Negev and violated the community's historic land rights.[12] In December 2013, the plan was rescinded.[13]

The Bedouin population in the Negev numbers 200,000–210,000. Just over half of them live in the seven government-built Bedouin-only towns; the remaining 90,000 live in 46 villages – 35 of which are still unrecognized and 11 of which were officially recognized in 2003.[2][10]

Characteristics

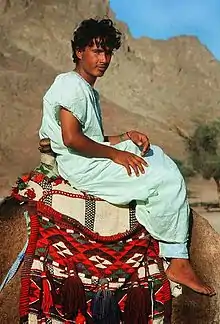

The Negev Bedouin used to be nomadic and later also semi-nomadic Arabs who live by rearing livestock in the deserts of southern Israel. The community is traditional and conservative, with a well-defined value system that directs and monitors behaviour and interpersonal relations.[14]

The Negev Bedouin tribes have been divided into three classes, according to their origin: descendants of ancient Arabian nomads, descendants of some Sinai Bedouin tribes, and Palestinian peasants (Fellaheen) who came from cultivated areas.[15] Al-Tarabin tribe is the largest tribe in the Negev and the Sinai Peninsula, Al-Tarabin along with Al-Tayaha, and Al-Azazma are the largest tribes in the Negev.[16]

Counter to the image of the Bedouin as fierce stateless nomads roving the entire region, by the turn of the 20th century, much of the Bedouin population in Palestine was settled, semi-nomadic, and engaged in agriculture according to an intricate system of land ownership, grazing rights, and water access.[17][18]

Today, many Bedouin call themselves 'Negev Arabs' rather than 'Bedouin', explaining that 'Bedouin' identity is intimately tied in with a pastoral nomadic way of life – a way of life they say is over. Although the Bedouin in Israel continue to be perceived as nomads, today all of them are fully sedentarized, and about half are urbanites.[19]

Nevertheless, Negev Bedouin continue to possess sheep and goats: In 2000 the Ministry of Agriculture estimated that the Negev Bedouin owned 200,000 head of sheep and 5,000 of goats, while Bedouin estimates referred to 230,000 sheep and 20,000 goats.[20]

History

Antiquity

Historically, the Bedouin engaged in nomadic herding, agriculture and sometimes fishing. They also earned income by transporting goods and people[21] across the desert.[22] Scarcity of water and of permanent pastoral land required them to move constantly. The first recorded nomadic settlement in Sinai dates back 4,000-7,000 years.[22] The Bedouin of the Sinai peninsula migrated to and from the Negev.[23]

The Bedouin established very few permanent settlements; however, some evidence remains of traditional baika buildings, seasonal dwellings for the rainy season when they would stop to engage in farming. Cemeteries known as "nawamis" dating to the late fourth millennium B.C. have been also found. Similarly, open-air mosques (without a roof) dating from the early Islamic period are common and still in use.[24] The Bedouin conducted extensive farming on plots scattered throughout the Negev.[25]

During the 6th century, Emperor Justinian sent Wallachian soldiers to the Sinai to build Saint Catherine's Monastery. Over time these soldiers converted to Islam, and adopted an Arab Bedouin lifestyle.[22]

Islamic era

In the 7th century, the Levant was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate. Later, the Umayyad dynasty began sponsoring building programs throughout the region, which was in close proximity to the dynastic capital in Damascus, and the Bedouin flourished. However, this activity decreased after the capital was moved to Baghdad during the subsequent Abbasid reign.[26]

Ottoman Empire

Most of the Negev Bedouin tribes migrated to the Negev from the Arabian Desert, Transjordan, Egypt, and the Sinai from the 18th century onwards.[27] Traditional Bedouin lifestyle began to change after the French invasion of Egypt in 1798. The rise of the puritanical Wahhabi sect forced them to reduce their raiding of caravans. Instead, the Bedouin acquired a monopoly on guiding pilgrim caravans to Mecca, as well as selling them provisions. The opening of the Suez canal reduced the dependence on desert caravans and attracted the Bedouin to newly formed settlements that sprung up along the canal.[22]

Bedouin sedentarization began under Ottoman rule[28] following the need in establishing law and order in the Negev; the Ottoman Empire viewed the Bedouins as a threat to the state's control.[17] In 1858, a new Ottoman Land Law was issued that offered the legal grounds for the displacement of the Bedouin. Under the Tanzimat reforms instituted as the Ottoman Empire gradually lost power, the Ottoman Land Law of 1858 instituted an unprecedented land registration process which was also meant to boost the empire's tax base. Few Bedouin opted to register their lands with the Ottoman Tapu, due to lack of enforcement by the Ottomans, illiteracy, refusal to pay taxes and lack of relevance of written documentation of ownership to the Bedouin way of life at that time.[29]

At the end of the 19th century Sultan Abdul Hamid II (Abdülhamid II) undertook other measures in order to control the Bedouin. As a part of this policy he settled loyal Muslim populations from the Balkan and Caucasus (Circassians) among the areas predominantly populated by the nomads, and also created several permanent Bedouin settlements, although the majority of them did not remain.[17] In 1900 an urban administrative center of Beersheva was established in order to extend governmental control over the area.

Another measure initiated by the Ottoman authorities was the private acquisition of large plots of state land offered by the sultan to the absentee landowners (effendis). Numerous tenants were brought in order to cultivate the newly acquired lands.

And the main trend of settling non-Bedouin population in the Palestine remained until the last days of the empire. By the 20th century much of the Bedouin population was settled, semi-nomadic, and engaged in agriculture according to an intricate system of land ownership, grazing rights, and water access.[30]

During World War I, the Negev Bedouin fought with the Turks against the British, but later withdrew from the conflict. Sheikh Hamad Pasha al-Sufi (died 1923), Sheikh of the Nijmat sub-tribe of the Tarabin, led a force of 1,500 men from Al-Tarabin, Al-Tayaha, Al-Azazma tribes which joined the Turkish offensive against the Suez Canal.[31]

British Mandate

The British Mandate in Palestine brought order to the Negev; however, this order was accompanied by losses in sources of income and poverty among the Bedouin. The Bedouin nevertheless retained their lifestyle, and a 1927 report describes them as the "untamed denizens of the Arabian deserts."[22] The British also established the first formal schools for the Bedouin.[14]

In Orientalist historiography, the Negev Bedouin have been described as remaining largely unaffected by changes in the outside world until recently. Their society was often considered a "world without time."[6] Recent scholars have challenged the notion of the Bedouin as 'fossilized,' or 'stagnant' reflections of an unchanging desert culture. Emanuel Marx has shown that Bedouin were engaged in a constantly dynamic reciprocal relation with urban centers.

[32] Bedouin scholar Michael Meeker explains that "the city was to be found in their midst."[33]

The British Mandate authorities, laws and bureaucracy favored settled groups above pastoral nomads and they found it hard to fit in the Negev Bedouin into their system of governance, thus the Mandate's policy regarding the Bedouin tribes of Palestine was often of an ad hoc nature.[17]

But eventually, as had happened with the Ottoman authorities, the British turned to coercion. Several regulations were issued, such as the Bedouin Control Ordinance (1942), meant to provide the administration with "special powers of control of nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes with the object of persuading them towards a more settled way of life". The ample powers of the Ordinance empowered the District Commissioner to direct the Bedouin "to go to, or not go to, or to remain in any specified area".[17]

Mandatory land policies created legal and demographic pressures for sedentarization, and by the end of the British Mandate the majority of the Bedouin were settled. They built some 60 new villages and dispersed settlements, populated by 27,500 people in 1945, according to the Mandate authorities.[17] The only exception were the Negev Bedouin who remained semi-nomadic, but it was clear that sooner or later they will be settled, too.

Prior to the founding of Israel, the Negev's population consisted almost entirely of 110,000 Bedouin.[34]

1948 war

During the 1948 war, Negev Bedouin favoured marginally both sides of the conflict;[35] most of them fled or were expelled to Jordan, Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank. In March 1948 Bedouin and semi-Bedouin communities begun to leave their homes and encampments in response to Palmach retaliation raids following attacks on water-pipelines to Jewish cities.[36] On 16 August 1948 the Negev Brigade launched a full-scale clearing operation in the Kaufakha-Al Muharraqa area displacing villagers and Bedouin for military reasons.[37] At the end of September the Yiftach Brigade launched an operation west of Mishmar Hanegev expelling Arabs and confiscating their livestock.[38] In early 1949 the Israeli army moved thousands of Bedouin from south and west of Beersheba to a concentration zone east of the town. In November 1949, 500 families were expelled across the border into Jordan and on September 2, 1950 some 4,000 Bedouin were forced across the border with Egypt.[39] Only around 11,000 of the 110,000 Bedouin population remained in the Negev.[40]

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli war, Nahum Sarig, the Palmach commander in the Negev, instructed his officers that "Our job is to appear before the Arabs as a ruling force which functions forcefully but with justice and fairness". With the provisions that they avoid harming women, children and friendly Arabs the orders stated that shepherds grazing on Jewish land should be driven off by gun-fire, that searches of Arab settlements be conducted "politely but firmly" and "you are permitted to execute any man found in possession of a weapon".[41]

Of the approximately 110,000 Bedouin who lived in the area before the war about 11,000 remained. Most had relocated from the northwestern to the northeastern Negev.[40]

Bedouin refugees in Jordan

Due to destabilizing tribal wars from 1780 to 1890 many Negev Bedouins tribes were forced to move to southern Jordan, Sinai peninsula. After the tribal war of 1890, tribal land boundaries remained fixed until the 1948 war, by which time the Beduin of the Negev numbered approximately 110,000, and were organized into 95 tribes and clans.[42]

When Beersheba was occupied by the Israeli army in 1948, 90% of the Bedouin population of the Negev were forced to leave, expectating to return to their lands after the war – mainly to Jordan and Sinai peninsula.[43] Of the approximately 110,000 Bedouin who lived in the Negev before the war about 11,000 remained.[40]

Israel

The first Israeli government headed by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion opposed the return of the Bedouin from Jordan and Egypt. At first he wanted to expel the few remaining Bedouin but changed his mind. The lands were nationalized and the area was declared a military zone. The government saw the Negev as a potential home for the masses of Jewish immigrants, including 700,000 Jewish refugees from Arab lands. In the following years, some 50 Jewish settlements were established in the Negev.[44]

The Bedouin who remained in the Negev belonged to the Al-Tiyaha confederation[25] as well as some smaller groups such as the 'Azazme and the Jahalin. They were relocated by the Israeli government in the 1950s and 1960s to a restricted zone in the northeast corner of the Negev, called the Siyagh (Arabic: السياغ Hebrew: אזור הסייג, an Arabic word that can be translated as the "permitted area") made up of in 10% of the Negev desert in the northeast.[45][46]

In 1951, the United Nations reported the deportation of about 7,000 Negev Bedouin to Jordan, the Gaza Strip and Sinai, but many returned undetected.[47] The new government failed to issue the Bedouin identity cards until 1952 and deported thousands of Bedouin who remained within the new borders.[48] Deportation continued into the late 1950s, as reported by the Haaretz newspaper in 1959: "The army's desert patrols would turn up in the midst of a Bedouin encampment day after day, dispersing it with a sudden burst of machine-gun fire until the sons of the desert were broken and, gathering what little was left of their belongings, led their camels in long silent strings into the heart of the Sinai desert."[19]

Land ownership issues

Israel's land policy was adapted to a large extent from the Ottoman land regulations of 1858. According to the 1858 Ottoman Land Law, lands that were not registered as of private ownership, were considered state lands. However, Bedouins were not motivated to register lands they lived on, because land ownership meant additional responsibilities for them, including taxation and military duty, and it created a new problem since they found it hard to prove their ownership rights. Israel relied mainly on Tabu recordings. Most of the Bedouin land fell under the Ottoman class of 'non-workable' (mawat) land and thus belonged to the state under Ottoman law. Israel nationalized most of the Negev lands, using The Land Rights Settlement Ordinance passed in 1969.[6][49]

Israel's policies regarding the Negev Bedouin at first included regulation and relocation. During the 1950s Israel has re-located two-thirds of the Negev Bedouins into an area that was under a martial law. Bedouin tribes were concentrated in the Siyagh (Arabic for "the permitted area") triangle of Beer Sheva, Arad and Dimona.[19]

At the same time Bedouin herding was restricted by land expropriation.[14] The Black Goat Law of 1950 curbed grazing, at least officially for the prevention of land erosion, thus prohibiting the grazing of goats outside recognized land holdings. Because few Bedouin territorial claims were recognized, most grazing was rendered illegal. Since both Ottoman and British land registration processes had failed to reach into the Negev region before Israeli rule, and since most Bedouin preferred not to register their lands, few Bedouin possessed any documentation of their land claims. Those whose land claims were recognized found it almost impossible to keep their goats within the periphery of their newly limited range. Into the 1970s and 1980s, only a small portion of the Bedouin were able to continue to graze their goats, and instead of migrating with their goats in search of pasture, most Bedouin migrated in search of work.[19]

Despite state hegemony over the Negev, the Bedouin regarded 600,000 dunams (600 km2 or about 150,000 acres) of the Negev as theirs, and later petitioned the government for their return.[50] Various claims committees were established to make legal arrangements to solve land disputes at least partially, but no proposals acceptable to both sides were approved.[49] In the 1950s, as a consequence of losing access to their lands, many Bedouin men sought work on Jewish farms in the Negev.[6] However, preference was given to Jewish labor, and as of 1958, employment in the Bedouin male population was less than 3.5%.[6]

IDF Chief Moshe Dayan was in favor of transfer the Bedouin to the center of the country in order to eliminate land claims and create a cadre of urban laborers.[44] In 1963, he told Haaretz:[51]

"We should transform the Bedouin into an urban proletariat—in industry, services, construction, and agriculture. 88% of the Israeli population are not farmers, let the Bedouin be like them. Indeed, this will be a radical move which means that the Bedouin would not live on his land with his herds, but would become an urban person who comes home in the afternoon and puts his slippers on. His children will get used to a father who wears pants, without a dagger, and who does not pick out their nits in public. They will go to school, their hair combed and parted. This will be a revolution, but it can be achieved in two generations. Without coercion but with governmental direction ... this phenomenon of the Bedouins will disappear."

Ben-Gurion supported this idea, but the Bedouin strongly opposed. Later, the proposal was withdrawn.

IDF commander Yigal Allon proposed to concentrate the Bedouin in some large townships within the Siyag. This proposal resembled an earlier IDF plan, which intended to secure land suitable for settling Jews and setting up IDF bases as well as to remove the Bedouin from key Negev routes.[44]

Israeli-built townships

Between 1968 and 1989 the state established urban townships for housing of deported Bedouin tribes and promised Bedouin services in exchange for the renunciation of their ancestral land.[44]

Within a few years, half of the Bedouin population moved into the seven townships built for them by the Israeli government.

The largest Bedouin locality in Israel is the city of Rahat, established in 1971. Other towns include Tel as-Sabi (Tel Sheva) (established in 1969), Shaqib al-Salam (Segev Shalom) in 1979, Ar'arat an-Naqab (Ar'ara BaNegev) and Kuseife in 1982, Lakiya in 1985 and Hura in 1989.[44][52][53]

Most of those who moved into these townships were the Bedouin with no recognized land claims, although the overwhelming majority of historic land claims had been left unrecognized by the Israeli government.[54]

According to Ben Gurion University's Negev Center for Regional Development, the towns were built without an urban policy framework, business districts or industrial zones;[55] as Harvey Lithwick of the Negev Center for Regional Development explains: "The major failure was a lack of an economic rationale for the towns."[56] According to Lithwick, and Ismael and Kathleen Abu Saad of Ben Gurion University, the towns quickly became among the most deprived towns in Israel, severely lacking in services such as public transport and banks.[14] The urban townships were plagued by endemic joblessness and resulting cycles of crime and drug trafficking.[55]

The Bedouin of Tarabin clan have moved into a township built for them, Tirabin al-Sana. The Bedouin of al-'Azazme clan will take part in the planning of a new quarter that will be erected for them to west of Segev Shalom township, cooperating with The Authority for the Regulation of Bedouin Settlement in the Negev.[57]

According to a State Comptroller report from 2002, the Bedouin townships were built with minimal investment, and infrastructure in the seven townships had not improved much in the span of three decades. In 2002, most homes were not connected to the sewage system, the water supply was erratic and the roads were not adequate.[58] Lessons were learned and new policies have been implemented since then, with the Israeli government allocating special funds to improve the wellbeing of the Negev Bedouin.

In 2008, a railway station opened near the largest Bedouin town in the Negev, Rahat (Lehavim-Rahat Railway Station), improving the transportation situation. Since 2009, Galim buses have been operating in Rahat.

Unrecognized villages

See article: Unrecognized Bedouin villages in Israel

Those Bedouin who resisted sedentarization and urban life remained in their villages. In 2007, 39-45 villages were not recognized by the state and were thus ineligible for municipal services such as connection to the electrical grid, water mains or trash-pickup.[54]

According to a 2007 report of the Israel Land Administration (ILA), 40% of the population were living in unrecognized villages.[59] Many insist on remaining in unrecognized rural villages in the hope of retaining their traditions and customs, some of which pre-date Israel.[46] However, in 1984, the courts ruled that the Negev Bedouin had no land ownership claims, effectively rendering their existing settlements illegal.[60] The Israeli government defines these rural Bedouin villages as "dispersals" while the international community refers to them as "unrecognized villages". Most Bedouin in unrecognized villages do not see urban townships as a desirable place to live.[61][62] Extreme unemployment has afflicted unrecognized villages as well, breeding extreme crime levels. Sources of income such as grazing have been severely restricted and the Bedouin rarely receive permits to engage in self-subsistence agriculture. However, in Besor Valley (Wadi Shallala), the ILA has leased JNF-owned land to Bedouin on a yearly-basis.[63]

Today, several unrecognized villages are in the process of recognition. They have been incorporated into the Abu Basma Regional Council created for the purpose of dealing with specific problems of the Bedouin. So far they remain without water, electricity and garbage services, although there is a certain improvement: for example, in al-Sayyid two new schools were built and a medical clinic has been opened since its recognition in 2004. Development has been hampered by urban planning difficulties and land ownership problems.[64] Due to the lack of municipal waste services and trash pickup, backyard burning has been adopted on a large scale, impacting badly on public health and the environment.[65]

Negev Bedouin claim the ownership of land totaling some 600,000 dunams (60,000 hectares or 230 square miles), or 12 times the size of Tel Aviv.[59] When land ownership claims reach the court, few Bedouin can supply enough evidence to prove ownership since land lots they claim have never been registered in the Tabu, which is the only official way to register them. For example, in the Al Araqeeb land ownership dispute, judge Sarah Dovrat has ruled in favor of the State, saying that the land was not "assigned to the plaintiffs, nor held by them under conditions required by law," and that they still had to "prove their rights to the land by proof of its registration in the Tabu."[66][67]

On September 29, 2003, the government adopted the new "Abu Basma Plan" (Resolution 881), calling for a new regional council to unify unrecognized Bedouin settlements, the Abu Basma Regional Council.[68] This resolution provided for the establishment of seven Bedouin townships in the Negev,[69] and recognizing previously unrecognized villages, which would be granted municipal status and consequently all basic services and infrastructure. The council was established by the Interior Ministry on 28 January 2004.[70]

In 2012, 13 Bedouin towns and cities were being built or expanded.[59] Several new industrial zones are planned, such as Idan HaNegev on the suburbs of Rahat.[71] It will have a hospital and a new campus inside.[72]

Prawer Plan

In September 2011, the Israeli government approved a five-year economic development plan called the Prawer Plan.[73] One of its implications is a relocation of some 30.000-40.000 Negev Bedouin from areas not recognized by the government to government-approved townships.[74][75] This will require Bedouins to leave ancestral villages, cemeteries and communal life as they know it.[75]

The plan is based on a proposal developed by a team headed by Ehud Prawer, the head of policy planning in the Prime Minister's Office (PMO). And this proposal, in its turn, is based on the recommendations of the committee chaired by retired Supreme Court Justice Eliezer Goldberg.[73] Maj.-Gen. (ret.) Doron Almog was appointed as the head of the staff to implement the plan to provide status for the Bedouin communities in the Negev.[76] Minister Benny Begin has been appointed by the cabinet to coordinate public and Bedouin population comments on the issue.[77]

According to the Israeli Prime Ministers Office, the plan is based on four main principles:

- Providing for the status of Bedouin communities in the Negev;

- Economic development for the Negev's Bedouin population;

- Resolving claims over land ownership; and

- Establishing a mechanism for binding, implementation and enforcement, as well as timetables.[73]

The plan was described as part of a campaign to develop the Negev; bring about better integration of Bedouin in Israeli society, and significantly reduce the economic and social gaps between the Bedouin population in the Negev and Israeli society.[73]

The cabinet also approved a NIS 1.2 billion economic development program for Bedouin Negev whose main purpose is to promote employment among Bedouin women and youth. Funding was allocated to the development of industrial zones, establishment of employment centers and professional training.

According to the Prawer Plan, Bedouin communities will be expanded, some unrecognized communities will be recognized and receive public services, and infrastructure will be renewed, all within the framework of the Beer Sheva District masterplan. Most residents will be absorbed into the Abu Basma Regional Council and the nature of future communities, whether agricultural, rural, suburban or urban will be decided in full cooperation with the local Bedouin. For those who are to be relocated, 2/3 will receive a new residence nearby.[73]

The Prawer Plan seeks to address the numerous land claims filed by the Bedouin, offering what the Israeli government states is "significant" compensation in land and funds, with each claim dealt with in a "unified and transparent way".[73]

The proposed solution will be put into binding legislation—the Israeli Knesset will work out and accept appropriate legislation in the fall of 2012. Accordingly, the state will reorganize and strengthen the enforcement mechanism. A team headed by minister Benny Begin and Maj.-Gen. (ret.) Doron Almog is responsible for the implementation of this plan.

Critics say the Prawer Plan will turn Bedouin dispossession into law[78][79] and come to a conclusion that relocation of the Bedouin will be compelled. Some even speak about ethnic cleansing.[80] Several members of the European Parliament have heavily criticized the plan.[81]

There are several examples of how the Prawer Plan has been implemented so far (As of June 2013): after a number of complicated discreet agreements with the state all of the Bedouin of Tarabin clan moved into a township built for them with all the amenities - Tirabin al-Sana.[59] Following negotiations, the Bedouin of al-'Azazme clan will take part in the planning of a new quarter that will be erected for them to the west of Segev Shalom, cooperating with The Authority for the Regulation of Bedouin Settlement in the Negev.[57]

In December 2013, the Israeli government shelved the plan to forcibly relocate about 40,000 Bedouin Arabs from their ancestral lands to government designated towns. One of the plan's architects stated that the Bedouin had neither been consulted nor agreed to the move. "I didn't tell anyone that the Bedouin agreed to my plan. I couldn't say that because I didn't present the plan to them," said the former minister Benny Begin.

The Association of Civil Rights in Israel stated that "the government now has an opportunity to conduct real and honest dialogue with the Negev Bedouin community and its representatives". The Negev Bedouin seek a solution to the problem of the unrecognised villages, and a future in Israel as citizens with equal rights."[82]

Resolution 3708

In September 2011, the government of Israel passed Resolution 3708, concerning the program to promote economic growth and development for the Bedouin population in the Negev. The Bureau for the Settlement and Economic Development of the Bedouin Sector in the Negev, which was at the time in the Prime Minister's Office, was given responsibility for supervising and monitoring the implementation of the development program.

Following government Resolution 1146 of January 5, 2014, responsibility for socioeconomic development and the status of Bedouin settlement in the Negev was transferred to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) and a program to integrate the Bedouin population in the Negev was initiated by the Planning Authority, which is the funding agency for monitoring and supervising implementation of the development program.

Resolution 3708 presented a five-year plan for 2012–2016 with goals of promoting the economic status of the Bedouin population in the Negev, strengthening Bedouin local authorities, and strengthening the social life, communities and leadership in the Bedouin population.

In order to achieve these goals, it was decided to focus investment on women and young adults, particularly in the areas of employment and education. The resolution addressed the following five areas:

- Raising the employment rate of the Bedouin population in the Negev, diversifying the places of employment, and increasing the integration of the Bedouin in employment in the Israeli economy

- Developing infrastructures, particularly those that support employment, education, and society

- Strengthening personal security

- Promoting education among the Bedouin in the Negev in order to increase their participation in the labor market

- Strengthening and developing social life within the community and leadership in the villages, and expanding social services.

Several ministries were involved in implementation of the resolution: Economy, Education, Social Affairs and Services (MOSAS), MARD, Interior, Public Security, Defense (Security-Social Division), Transport and Road Safety, Culture and Sport, Development of the Negev and the Galilee, and Health.

The total budget for implementation of the resolution was NIS 1.2633 billion, of which 68% was a supplementary sum (not taken from the budgets of the ministries).

Clause 11 of Resolution 3708 stipulated that the program should be examined by an evaluation study. MARD commissioned the Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute to examine the implementation of the resolution and its outcomes over a 3-year period. The study focused on four core areas that were important to the development and advancement of the Bedouin population and that represented 77% of the total budget allocated for the resolution (employment, social infrastructures, personal security, and education,

Following two interim reports,[83][84] a final evaluation was released in 2018.[85] Among the findings were the following:

- Establishing Riyan Employment Centers. The Riyan Centers provide participants with vocational guidance, professional training and job placement, and are situated in the communities themselves to take advantage of local resources. Prior to Resolution 3708, the centers operated in two only localities. With the implementation, they were distributed throughout all Bedouin local authorities and reached almost 10,000 people. About 50% of the men and 30% of the women were placed in jobs within a year of joining.[86]

- Practical Engineering Studies for Adults. Prior to the Resolution, Bedouin students in the Shiluv Program studied in separate college classes. Following the Resolution, the study model was changed, with students integrated into regular college classes and also receiving financial and personal support. As of 2017, 305 students had entered the engineering track, a quarter of whom were women.[87]

- Improved Access to Transportation. Since the Resolution, the number of inter-city trips increased by 94%, and of intra-city trips, by 43%.[87]

- Centers of Excellence. The Centers of Excellence are offer a weekly after-school program for students in grades 3–6, with a compulsory course in science and technology and an elective in a choice of subjects. Six centers became operative under the Resolution and, in 2017, served some 900 students.[88]

Healthcare

The Bedouin benefited from the introduction of modern health care in the region.[6] According to the World Zionist Organization, although in the 1980s, as compared with 90% of the Jewish population, only 50% of the Bedouin population was covered by Israel's General Sick Fund, the situation improved after the 1995 National Health Insurance Law incorporated another 30% of Negev Bedouin into the Sick Fund.[89] There are branches of several health funds (medical clinics) operating in the seven Bedouin townships: Leumit, Clalit, Maccabi and perinatal (baby care) centers Tipat Halav.

The Bedouin infant mortality rate is still the highest in Israel, and one of the highest in the developed world. In 2010, the mortality rate of Bedouin babies rose to 13.6 per 1,000, compared to 4.1 per 1,000 in Jewish communities in the south. According to the Israeli Ministry of Health, 43 percent of deaths among infants up to a year old result from hereditary conditions and/or birth defects. Other reasons cited for the higher infant mortality rates are poverty, lack of education and proper nourishment of mothers, lack of access to preventive medical care and unwillingness to undergo recommended tests. In 2011, funding for this purpose was tripled.[90]

60% of Bedouin men smoke. Among the Bedouin, as of 2003, 7.3% of females and 9.9% of males have diabetes.[91] Between 1998 and 2002, Bedouin towns and villages had among the highest per-capita hospitalization rates, Rahat and Tel Sheva ranked highest.[92] However, the rate of reported new cancer incidents in Bedouin localities is very low, with Rahat having the 3rd-lowest rate in Israel at 141.9 cases per 100,000, compared to 422.1 cases in Haifa.[92]

The Centre for Women's Health Studies and Promotion notes that in the unrecognised Bedouin villages in the Negev, very few health care facilities are available; ambulances do not serve the villages and 38 villages have no medical services.[93] According to the Israeli NGO Physicians for Human Rights-Israel the number of doctors is a third of the norm.[94]

In urban townships, access to water is also an issue: an article from the World Zionist Organization Hagshama Department explains that water allocation to Bedouin towns is 25-50% of that to Jewish towns.[89] Since the State has not built water infrastructure in the unrecognized villages, residents must buy water and store it in large tanks where fungi, bacteria and rust develop very quickly in the plastic containers or metal tanks under conditions of extreme heat; this has led to numerous infections and skin diseases.[94]

Education

In the 1950s, mandatory schooling was extended to the Bedouin sector, leading to a massive increase in literacy levels. Illiteracy decreased from around 95% to 25% within the span of a single generation, with the majority of the illiterate being 55 or older.[95]

Drop-out rates were once very high among Negev Bedouin. In 1998 only 43 percent of Bedouin youngsters reached the 12th grade.[58] Enforcement of mandatory education for the Bedouin was weak, particularly in the case of young girls. According to a 2001 study by the Centre for Women's Health Studies and Promotion more than 75% of Bedouin women had never been to or completed elementary school.[93] This was due to a combination of internal Bedouin traditional attitudes towards women, lack of government enforcement of the Mandatory Education Law and insufficient budgets for Bedouin schools.[93]

However, the number of Bedouin students in Israel is on the rise. Arabic summer schools are being developed.[96] In 2006, 162 Bedouin men and 112 Bedouin women were studying at Ben Gurion University. In particular, the number of female students grew sixfold from 1996 to 2001.[97] The university offers special Bedouin scholarship programs to encourage higher education among the Bedouin.[98] In 2013, there were 350 Bedouin women and 150 Bedouin men studying at Ben Gurion University.[99]

According to data released by the Knesset Research and Information Center in July 2012, at least 800 young Bedouins from the Negev (out of overall 1300 Israeli students studying in PA) opted for universities in the Palestinian Authority, mainly Hebron and Jenin, preferring Muslim studies (Sharia) and education.[100] It's a relatively new phenomenon, occurring in the past year or two and its main reasons are relatively difficult psychometric exams hampering to be accepted into Israeli universities and colleges (in PA there is no such a requirement), absence of Muslim studies subject in them and a language barrier.[101]

In fall 2011 Ben-Gurion University of the Negev has revived a special program preparing Bedouins to fill a dire need in school psychologists in their communities' schools due to a host of issues particular to this population, from aged-old inter-clan rivalries to the emotional fallout from polygamy. This program is leading to a master's degree in educational psychology for Arab-Israeli and Bedouin students. Program's leaders admit that only a professional from within the society can fully understand the intricacies of its unique situations.[102]

Additionally, a new Harvard University campus will be established in Rahat inside Idan HaNegev industrial zone in the coming years. It will be the first campus built in this Bedouin city.[103] Ben-Gurion University of the Negev will oversee the new campus' operations, and it will be considered a BGU branch.

A few years ago the Association of Academics for the Development of Arab Society in the Negev (AHD) has established a new science high school at the Shoket Junction. This school hosts some 380 students in grades nine through twelve from Bedouin Arab towns and villages. First students graduated it in the spring of 2012.[104]

Women's status

According to a range of studies, including a 2001 study by the Centre for Women's Health Studies and Promotion at Ben Gurion University, in the transition from self-subsistence agriculture and animal husbandry to a settled semi-urban lifestyle, women have lost their traditional sources of power within the family. The study explains that poor access to education among women has triggered new disparities between Bedouin men and women and compounded the loss of Bedouin women's status in the family.[105] Nevertheless, due to high levels of poverty among the Bedouin more and more Bedouin women are starting to work outside their homes and reinforce their status. However, some of these women encounter fierce resistance from family members, and in some cases have experienced physical violence and even murder.

There were reports that some Bedouin tribes had previously conducted female genital mutilation. However, this practice was considered far less severe than what is carried out in some places in Africa, consisting of a "small" cut. The practice was carried out independently by women, and men didn't play a part and in most cases were unaware of the practice. However, by 2009 the practice seemed to have disappeared. Researchers are unclear as to how it disappeared (the Israeli government was not involved) but suggest modernisation as the probable cause.[106]

Economy

Traditionally given over to shepherding their flocks and foraging for edible roots and herbs, while living a nomadic way of life, many Bedouins, since the mid–late 20th-century, have been forced to relocate and move into permanent settlements. This change has disrupted their traditional way of life and has, subsequently, affected many changes in the community. The Negev Bedouin suffer from extreme rates of joblessness and the highest poverty rate in Israel. A 2007 Van Leer Institute study found that 66 percent of Negev Bedouin lived below the poverty line (in unrecognized villages, the figure reached 80 percent), compared 25 percent in the Israeli population.[107]

Data collected by the Industry, Trade and Labor Ministry in 2010 show that the employment rate among the Bedouin is 35 percent, the lowest of any sector in Israeli society.[108] Traditionally, Bedouin men are the breadwinners, while Bedouin women do not work outside the home.

As of 2012, 81 percent of Bedouin women of working age were unemployed.[109] Nevertheless, a growing number of women have begun to join the work force.[110]

Several NGOs are helping to expand entrepreneurship by providing professional training and guidance. Twenty Arab-Bedouin women from Rahat, Lakiya, Tel Sheva, Segev Shalom, Kuseife and Rachma participated in a sewing course for fashion design at Amal College in Beer Sheva, including lessons on sewing and cutting, personal empowerment and business initiatives.[111] As a result, tourism and crafts are growing industries and in some cases, such as Drijat, have reduced unemployment significantly.[96] The new industrial zones being constructed in the region are also increasing job opportunities.

Crime

The crime rate in the Bedouin sector in the Negev is among the highest in the country.[112] To that end, a special police unit, codenamed Blimat Herum (lit. emergency halt), consisting of about 100 regular policemen, was founded in 2003 to fight crime in the sector. The Southern District of the Israel Police cited the rising crime rate in the sector as the reason for the unit's inauguration. The unit was founded after a period of time when regular police units conducted raids on Bedouin settlements to stop theft (especially car theft) and drug dealing.[113] In 2004 a new police station was opened in Rahat, it has around 70 staff policemen.

Environmental issues

In 1979, a 1,500 square kilometer area in the Negev was declared a protected nature reserve, rendering it out of bounds for Bedouin herders. In conjunction with this move the Green Patrol, a law compliance unit was established that disbanded 900 Bedouin encampments and cut goat herds by more than a third. With the black goat nearly extinct, black goat hair to weave tents is hard to come by.[114]

Israeli environmental leader Alon Tal claims Bedouin construction is among the top ten environmental hazards in Israel.[115] In 2008, he wrote that the Bedouin are taking up open spaces that should be used for park land.[116] In 2007, Bustan organization disagreed with this contention: "Regarding rural Bedouin land use as a threat to open spaces fails to take into account the fact that Bedouin occupy little more than 1% of the Negev and fails to call into question the IDF's hegemony over more than 85% of the Negev's open spaces."[52] Gideon Kressel has proposed a brand of pastoralism that preserves open spaces for rangeland herding.[117]

Wadi al-Na'am is located close to the Ramat Hovav toxic waste dump, and its residents have suffered from higher than average incidences of respiratory illnesses and cancer.[118] Given the small scale of the country, Bedouin and Jews of the region share some 2.5% of the desert with Israel's nuclear reactors, 22 agro and petrochemical factories, an oil terminal, closed military zones, quarries, a toxic waste incinerator (Ramat Hovav), cell towers, a power plant, several airports, a prison, and 2 rivers of open sewage.[119]

Demographics

The Bedouin comprise the youngest population in Israeli society - about 54 percent of the Bedouin population was younger than 14 in 2002.[58] With an annual growth rate of 5.5% that same year,[58] which is one of the highest in the world, the Bedouin in Israel were doubling their population every 15 years.[59] Bedouin advocates argue that the main reason for the transfer of the Bedouin into townships against their will is demographic.[120] In 2003, Director of the Israeli Population Administration Department, Herzl Gedj,[121] described polygamy in the Bedouin sector a "security threat" and advocated various means of reducing the Arab birth rate.[122] In 2004, Ronald Lauder of the Jewish National Fund, announced plans to increase the number of Jews in the Negev by 250,000 in five years and 500,000 in ten years into the Negev through the Blueprint Negev,[123] incurring opposition from Bedouin rights groups concerned that the unrecognized villages might be cleared to make way for Jewish-only development and potentially ignite internal civil strife.[124]

In 1999, 110,000 Bedouin lived in the Negev, 50,000 in the Galilee and 10,000 in the central region of Israel.[125] As of 2013, the Bedouin population in the Negev numbered 200,000-210,000.[1][2][3]

Identity and culture

The Bedouin consider themselves Arabs with their origin being modern Saudi Arabia. The Bedouins are seen as Arab culture's purest representatives, "ideal" Arabs, but they are distinct from other Arabs because of their extensive kinship networks, which provide them with community support and the basic necessities for survival.

The Negev Bedouin have been compared to the American Indians in terms of how they have been treated by the dominant cultures.[6] The Regional Council of Unrecognized Villages describes the Negev Bedouin as an "indigenous" population.[126] However, some researchers contest this view.[127]

The Bedouin have their own authentic and distinct culture, rich oral poetic tradition, honor code and a code of laws. Despite the problem of illiteracy, the Bedouin attribute importance to natural events and ancestral traditions.[128] The Bedouin of Arabia were the first converts to Islam, and it is an important part of their identity today.[5]

Their outfit is also different from that of other Arabs, since the men wear long 'jellabiya' and a 'smagg' (red white draped headcover) or 'aymemma' (white headcover) or a white small headdress, sometimes held in place by an 'agall' (a black cord). Bedouin women usually wear brightly coloured long dresses but outside they wear 'abaya' (a thin, long black coat sometimes covered with shiny embroidery) and they will always cover their head and hair with a 'tarha' (a black, thin shawl) when they leave their house.[129]

Traditional skill-crafts

The Bedouin women of the Negev were once renowned for their skills in making black, goat-hair matted tent flaps for constructing tents (known locally as bayt al-shar), but this practice is now nearly lost and found almost exclusively among Bedouins in Jordan. Still, the Bedouins of the Negev have maintained and passed down certain skill crafts, such as basketry and weaving rope with a plant fiber known to them as mitnān, or what is called in English "shaggy sparrow-wort" (Thymelaea hirsuta),[130] and dyeing wool with a yellow dye extracted from the stalks and roots of the Desert broomrape (Cistanche tubulosa), a plant known locally by the name dhunūn and halūq.[131]

Bedouins of the Negev and Sinai have traditionally made use of the solidified resin extracted from the seeds of the ban tree (Moringa peregrina) to treat (rosin) the strings of the Arab violin (rebābah).[132]

Glue was made from the siyāl tree (Acacia raddiana), by mixing its sap with warm water.[132]

Attitude towards Israel

Many Bedouin serve as trackers in the IDF's elite tracking units, tasked with securing the border from infiltration.[133] Amos Yarkoni, first commander of the Shaked Reconnaissance Battalion in the Givati Brigade, was a Bedouin (born Abd el-Majid Hidr), although not from the Negev.

The circulated number of Bedouin of draft age volunteering for the Israeli army each year (unlike Druze, Circassian[134] and Jewish Israelis, they are not required to serve), varies quite a bit: it is between 5%-10%,[135][136] or, as estimated by Doron Almog, head of Israel's Bedouin Improvement Program Staff, in August 2012, it stands at half a percentage of eligible Bedouins.[137] A 2013 source sets the number of Bedouin servicemen on active duty at about 1,600, two-thirds of whom come from the north.[133] Accorging to The Economist, the Bedouin who were once "unusual among Israel's Arabs for their readiness to serve in Israel's army" have slumped in volunteers "to a mere 90 of 1,500-plus men eligible to join up every year" due to a souring of relations between Bedouin and Jewish Israelis.[138]

A 2001 poll suggests that Bedouin feel more estranged from the state than do Arabs in the north. A Jewish Telegraphic Agency article reports that, "forty-two percent said they reject Israel's right to exist, compared with 16 percent in the non-Bedouin Arab sector."[58] But a 2004 study found that Negev Bedouins tend to identify more as Israelis than other Arab citizens of Israel.[139]

Ismail Khaldi is the first Bedouin vice consul of Israel and the highest ranking Muslim in the Israeli foreign service.[140] Khaldi is a strong advocate of Israel. While acknowledging that the Israeli Bedouin minority is not ideal, he said:

I am a proud Israeli – along with many other non-Jewish Israelis such as Druze, Baháʼí, Bedouin, Christians and Muslims, who live in one of the most culturally diversified societies and the only true democracy in the Middle East. Like America, Israeli society is far from perfect, but let us deals honestly. By any yardstick you choose—educational opportunity, economic development, women and gays' rights, freedom of speech and assembly, legislative representation—Israel's minorities fare far better than any other country in the Middle East.[141]

Relationship with Palestinians

Before 1948 the relationships between Negev Bedouin and the farmers to the north was marked by intrinsic cultural differences as well as common language and some common traditions. Whereas the Bedouin referred to themselves as "arab" instead of "bedû" (Bedouin), "fellahîn" (farmers) in the area used the term Bedû, meaning "inhabitants of the desert" (Bâdiya), more often.[142]

While both are Arabs, some Palestinians do not consider the Bedouin to be Palestinian, and elements within the Negev/Naqab Bedouin do not consider themselves Palestinian.[143] However, some scholars regard distinct people's attempt to maintain their historic identity as an illustration of a strategy of 'Divide to Rule',[144] and in recent years, Palestinian nationalistic and Islamic movements have gained increasing prominence at the expense of their historically neutral and tribal based self-identification, filling the void caused by strained relations with the state.[145][146]

A 2001 study suggested that regular meetings and cross border exchanges with relatives or friends in the West Bank, Gaza Strip and Sinai are more common than expected, casting doubt on the accepted view of the relationship between the Bedouin and Palestinians.[142]

Gallery

One of Rahat community centers

One of Rahat community centers A private house in Tirabin al-Sana, a settlement of the Tarabin bedouin

A private house in Tirabin al-Sana, a settlement of the Tarabin bedouin An entrance to the Bedouin village al-Sayyid

An entrance to the Bedouin village al-Sayyid One of Hura's schools

One of Hura's schools Rahat city view

Rahat city view At the streets of Rahat

At the streets of Rahat An industrial park Idan HaNegev being built in close proximity to Rahat

An industrial park Idan HaNegev being built in close proximity to Rahat Private home in Segev Shalom

Private home in Segev Shalom One of two al-Sayyid schools

One of two al-Sayyid schools A view at Rahat from a new fast growing neighborhood Rahat haHadasha

A view at Rahat from a new fast growing neighborhood Rahat haHadasha Private house in al-Sayyid

Private house in al-Sayyid

See also

References

- "Arrests at protest over Israel's Bedouin plan". Al Jazeera English. 1 December 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Noreen Sadik (23 July 2013). "Israel's Bedouin population faces mass eviction -- New Internationalist". Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- "Behind the Headlines: The Bedouin in the Negev and the Begin Plan". Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Yahel, Havatzelet; Kark, Ruth (2 January 2015). "Israel Negev Bedouin during the 1948 War: Departure and Return". Israel Affairs. 21 (1): 48–97. doi:10.1080/13537121.2014.984421. ISSN 1353-7121. S2CID 143770058.

- "Bedouin Life". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Kurt Goering (Autumn 1979). "Israel and the Bedouin of the Negev". Journal of Palestine Studies. 9 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1525/jps.1979.9.1.00p0173n.

- Porat, Khanina (2000). "The State of Israel's Measures and the Left's Alternatives for the Resolution of the Negev Bedouins Dispute 1953-1960" (PDF). עיונים בתקומת ישראל. 10: 420–479 – via Ben Gurion University.

- "Ministry of Justice & Ministry of Foreign Affairs: List of Issues to be taken up in Connection with the Consideration of Israel's Fourth and Fifth Periodic Reports of Israel, November 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- "Bedouins in the State of Israel". Knesset homepage. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- "Israel's bedouin battle displacement". Al Jazeera. 29 August 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Protesters clash with police over Bedouin displacement plan". CNN. 30 November 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Bedouins in Israel Protest Plan to Regulate Settlement". The New York Times. 1 December 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Seidler, Shirly (2 December 2013). "Israeli Government Claims 80% of Bedouin Agree to Resettlement; Bedouin Leader: State Is Lying". Haaretz. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Abu Saad, Ismael (1991). "Towards an Understanding of Minority Education in Israel: The Case of the Bedouin Arabs of the Negev". Comparative Education. 27 (2): 235. doi:10.1080/0305006910270209.

- "Nabataea Negev". Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Biger, Gideon (2004). The Boundaries of Modern Palestine, 1840-1947. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7146-5654-0. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Dr. Seth J. Frantzman, Ruth Kark Bedouin Settlement in Late Ottoman and British Mandatory Palestine: Influence on the Cultural and Environmental Landscape, 1870-1948

- Givati-Teerling, Janine (February 2007). "Negev Bedouin and Higher Education" (PDF). Sussex Centre for Migration Research (41). Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- Manski, Rebecca (25 March 2007). "The Scene of Many Crimes: Criminalizing Self-Subsistence". AIC.

- Aref Abu Rabia. "Employment and Unemployment among the Negev Bedouin"; Nomadic Peoples, Vol. 4, 2000

- HIDDEN HISTORY, SECRET PRESENT: THE ORIGINS AND STATUS OF AFRICAN PALESTINIANS, Susan Beckerleg, translated by Salah Al Zaroo On Africans in the Negev Desert

- Martin Ira Glassner (January 1974). "The Bedouin of Southern Sinai under Israeli Administration". Geographical Review. 64 (1): 31–60. doi:10.2307/213793. JSTOR 213793.

- Clinton Bailey (1985). "Dating the Arrival of the Bedouin Tribes in Sinai and the Negev". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 28 (1): 20–49. doi:10.1163/156852085X00091.

- Israel Finkelstein; Avi Perevolotsky (August 1990). "Processes of Sedentarization and Nomadization in the History of Sinai and the Negev". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 279 (279): 67–88. doi:10.2307/1357210. JSTOR 1357210. S2CID 162287535.

- Lustick, Ian (1980). Arabs in the Jewish State. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 57, 134–136. ISBN 978-0-292-70348-3.

- Uzi Avner; Jodi Magness (May 1998). "Early Islamic Settlement in the Southern Negev". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 310 (310): 39–57. doi:10.2307/1357577. JSTOR 1357577. S2CID 163609232.

- Frantzman, Seth J.; Yahel, Havatzelet; Kark, Ruth (2012). "Contested Indigeneity: The Development of an Indigenous Discourse on the Bedouin of the Negev, Israel". Israel Studies. 17 (1): 78–104. doi:10.2979/israelstudies.17.1.78. ISSN 1084-9513. JSTOR 10.2979/israelstudies.17.1.78. S2CID 143785060.

- Jodi Magness, The Archaeology of the Early Islamic Settlement in Palestine, Eisenbrauns, 2003, p.82

- Gershon Shafir, Land, Labor and the Origins of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict, 1882–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Ghazi Falah. "The Spatial Pattern of Bedouin Sedentarization in Israel," GeoJournal, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 361–368; 1985 ("Semi-nomadic" in this case refers to movement within a limited 12–13 km radius), cited in: Manski (2006), see at "References"

- Palestine Exploration Quarterly (October 1937). Page 244.

- Marx, Emanuel (2012). "Nomads and Cities: The Development of a Conception". In Hazan, Haim; Hertzog, Esther (eds.). Serendipity in Anthropological Research: The Nomadic Turn. Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. pp. 31–46. ISBN 978-1-4094-3058-2.

- Meeker, Michael (2005). "Magritte on the Bedouins: Ce n'est pas une societé segmentaire". In Leder, Stefan; Steck, Bernhard (eds.). Shifts in Nomad-sedentary Relations. Nomaden und Sesshafte 2. Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 77–98.

- "The Naqab (Negev) Under the Microscope: Roots, Reality, Destiny". Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- Frédéric Encel (in French), Géopolitique d'Israël : "Lors de la première guerre israélo-arabe de 1948-1949, les Bédouins n'interviennent que marginalement d'un côté ou de l'autre. La grande majorité des 65 000 Bédouis du Néguev fuit les combats pour se réfugier en Transjordanie ou en Egypte (Sinaï)"

- Morris. Page 57.

- Khalidi, 1992, p.127.

- Morris. Page 215.

- Morris. Page 246.

- "The Bedouin Population in the Negev" (PDF). europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- Morris, Benny (1987) The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33028-9. Page 36.

- Abu-Saad, Ismael (1997). "Project MUSE - The Education of Israel's Negev Beduin: Background and Prospects". Israel Studies. 2 (2): 21–39. doi:10.2979/ISR.1997.2.2.21. S2CID 144540424. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Talab el-Sana (5 October 2011). "The plight of the Negev's Bedouin". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Shlomo Swirski and Yael Hasson. "INVISIBLE CITIZENS: Israel Government Policy Toward the Negev Bedouin"; Adva Center, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev: Center for Bedouin Studies & Development Research Unit and, Negev Center for Regional Development, 2006. PDF

- Hamdan, H. "The Policy of Settlement and Spatial Judaization in the Naqab" Adalah News (11 -2005)

- "The Indigenous Bedouin of the Negev Desert in Israel" (PDF). Negev Coexistence Forum. p. 8.

- Cook, Jonathan. BEDOUIN "TRANSFER". MERIP. May 10, 2003. Retrieved July 4th, 07.

- Masalha, Nur, A Land Without People: Israel, Transfer and the Palestinians, 1949–1996 (London: Faber and Faber, 1997)

- Fenster, Tobi (in Hebrew). A summary stance paper on Bedouin land issues, written for "Sikkuy - for equal opportunity".

- "The Beduin of the Negev", Israel Land Administration, updated as of March 11, 2007

- "End of the road for the Bedouin - Middle East, World - The Independent". Independent.co.uk. 13 August 2010. Archived from the original on 13 August 2010.

- Rebecca Manski. "The Nature of Environmental Injustice in Bedouin Urban Townships: The End of Self-Subsistence" Archived 2011-10-03 at the Wayback Machine (translation from Hebrew), originally published in Hebrew by the "Life & Environment" NGO coalition in: "Environmental Injustice Report 2006"[elsewehere: 2007 - ?]

- Jonathan Cook."Bedouin in the Negev face new 'transfer"; MERIP, May 10, 2003

- "Off the Map: Land and Housing Rights Violations in Israel's Unrecognized Bedouin Villages"; Human Rights Watch, March 2008 Volume 20, No. 5(E). Whole report: (PDF, 5.4 MiB)

- Harvey Lithwick, Ismael Abu Saad, Kathleen Abu-Saad, Merkaz HaNegev LeFitu'ah Ezori and Merkaz LeHeker HaHevra HaBeduit VeHitpathuta (Israel). "A Preliminary Evaluation of the Negev Bedouin Experience of Urbanization: Findings of the Urban Household Survey"; Negev Center for Regional Development, 2004

- Harvey Lithwick, "An Urban Development Strategy for the Negev's Bedouin Community", The Center for Bedouin Studies and Development, Ben Gurion University (2000)

- Yanir Yagna, For the first time: Bedouin to take part in planning of their new neighborhood (Hebrew), Haaretz, July 1, 2012

- Nir, Or."Israel largely ignoring growth, needs of Bedouin community" Jewish Telegraphic Agency, May 10, 2002

- "Bedouin of the Negev (ILA brochure)" (PDF). Israel Land Administration (ILA). 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- Qupty, Maha. "Bedouin Unrecognized Villages of the Negev" Archived 2013-03-08 at the Wayback Machine; De la Marginación a la Ciudadanía, 38 Casos de Production Social del Hábitat, Forum Barcelona, Habitat International Coalition. Case study, 2004

- Jonathan Cook.Making the land without a people" Archived 2009-01-06 at the Wayback Machine; Al-Ahram Weekly, 26 Aug-1 Sep 2004

- Chris McGreal."Bedouin feel the squeeze as Israel resettles the Negev desert: Thousands displaced from ancient homeland; The Guardian, February 27, 2003

- Aref Abu-Rabia. The Negev Bedouin and Livestock Rearing: Social, Economic, and Political Aspects, Oxford, 1994, pp. 28, 36, 38

- Knesset protocols regarding the unrecognized villages (Hebrew)

- Yaakov Garb; Ilana Meallam. "The Exposure of Bedouin Women to Waste Related Hazards Gender, Toxins and Multiple Marginality in The Negev (Israel)" (PDF). Women and Environments (Fall/Winter 2008).

- Civil Case File Nos. 7161/06, 7275/06, 7276/06 1114/07, 1115/07, 5278/08, Suleiman Mahmud Salaam El-Uqbi (deceased) et. al. v. The State of Israel et. al. (15.3.12) Archived 2012-12-18 at archive.today

- Jerusalem Post, "Court rejects 6 Bedouin Negev land lawsuits", March 19, 2012.

- Beduin in Limbo Archived 2013-07-06 at archive.today The Jerusalem Post, 24 December 2007

- Government resolutions passed in recent years regarding the Arab population of Israel Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine Abraham Fund Initiative

- The Bedouin Population in Transition: Site Visit to Abu Basma Regional Council Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute, 28 June 2005

- "Idan Hanegev Industrial Park". Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- Itamar Eichner, Harvard University makes aliyah, ynet, April 1, 2012

- Cabinet Approves Plan to Provide for the Status of Communities in, and the Economic Development of, the Bedouin Sector in the Negev, PMO official site, September 11, 2012

- Al Jazeera, 13 September 2011, "Bedouin transfer plan shows Israel's racism"

- Guardian, 3 November 2011, "Bedouin's plight: 'We want to maintain our traditions. But it's a dream here'"

- Maj.-Gen. (ret.) Doron Almog to be Appointed as Head of the Staff to Implement the Plan to Provide Status for the Bedouin Communities in the Negev, PMO official site, December 1, 2011

- Cabinet approves Prawer Report to resolve land issues in the Negev Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine, UK Task Force, September 19, 2011

- Bill will turn Bedouin dispossession into Israeli law Archived 2012-04-24 at the Wayback Machine, Alternative news, January 2, 2012

- Neve Gordon, Uprooting 30,000 Bedouin in Israel, Al Jazeera, April 3, 2012

- The Real Social Justice Movement, David Sheen for Haaretz, 11 November 2011

- Haaretz, 8 July 2012, European Parliament condemns Israel's policy toward Bedouin population

- Harriet Sherwood (12 December 2013). "Israel shelves plan to forcibly relocate Bedouin from desert lands". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Dr. Yonatan Eyal, Dr. Hagit Sofer Furman, Suzan Hassan-Daher, and Moria Frankel. 2016. Program to Promote Economic Growth and Development for the Bedouin Population in the South of Israel. (Government Resolution 3708) – First Report. Jerusalem: Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute.

- Dr. Yonatan Eyal, Suzan Hasan, Moria Frankel, and Judith King (2016). Promoting Economic Growth and Development of the Bedouin Population in Southern Israel: Education – Second Report on Government Decision 3708. Jerusalem: Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute.

- Dr. Yonatan Eyal, Oren Tirosh, Judith King, and Moria Frankel. 2018. The Program to Promote Economic Growth and Development for the Bedouin Population in the Negev Government Resolution 3708. Jerusalem: Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute.

- Eyal, Tirosh, King, and Frankel, 12.

- Eyal, Tirosh, King, and Frankel, 13.

- Eyal, Tirosh, King, and Frankel, 15.

- Suzanna Kokkonen. "The Bedouins of the Negev confront a modern society"; World Zionist Organization Hagshama Department, October 31, 2002

- "Israeli Bedouin Women Lack Access to Prenatal Care". Haaretz. 24 April 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- "The Negev is the southern region of Israel and is an ideal location for implementing community intervention programmes for populations in transition" Archived 2008-05-31 at the Wayback Machine; Oxford Health Alliance, 2008

- "New Publication: Socio-Medical Profile of Israeli Localities Between 1998 and 2002". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 7 November 2005. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- "Briefing to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women"; Amnesty International, 2005 (citing J. Cwikel and N. Barak, Health and Welfare of Bedouin Women in the Negev, The Centre for Women's Health Studies and Promotion, Ben Gurion University, 2001)

- "Without Water! Position Paper on the Right to Water in Unrecognized Villages"; PHR-Israel September 2004

- "The Bedouin in Israel". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- A Bedouin growth industry Haaretz, 2 July 2007

- Bedouin graduates final 18042007

- Research tenders, The Center for the studies of the Bedouin community and its development (Hebrew)

- "More Bedouin women turn to academia". ynet. 21 October 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Yanir Yagna, Israel's Bedouin are opting for West Bank universities, Haaretz, July 29, 2012

- Tomer Velmer, [Leap in number of Israelis studying in PA http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4181944,00.html], Ynetnews, January 28, 2012

- Abigail Klein Leichman, Wanted: Bedouin school psychologists, Israel 21c, July 30, 2012

- Eichner, Itamar (April 2012). "Harvard University makes aliyah". ynet. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Israeli Science High School Advances Bedouin Community, August 15, 2011

- J. Cwikel and N. Barak, Health and Welfare of Bedouin Women in the Negev, The Centre for Women's Health Studies and Promotion, Ben Gurion University, 2001

- "Bedouins shunning FGM/C - new research". IRIN. 4 March 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Ruth Sinai. "66% of Negev Bedouin live below poverty line"; Haaretz, January 15, 2007

- Ron Friedman, Ministers inaugurate new projects in South to help Beduins, Jerusalem Post, April 28, 2010

- FEATURE-Mosque doubles as work haven to Israel's Bedouin women, Reuters, June 27, 2012

- Rising number of Bedouin women enter work force, Al Arabiya, July 1, 2012

- Economic Empowerment. Arab-Bedouin Fashion Design Archived 2013-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Phoebe Greenwood, Bedouin land and culture threatened by Israel's plans for resettlement, The Guardian, May 9, 2012

- חלפון, ארצי (1 November 2003). "נא להכיר: היחידה המשטרתית למלחמה בפשע במגזר הבדואי". Ynet – via www.ynet.co.il.

- Ghazi Falah. "How Israel Controls the Bedouin in Israel," Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. XIV, No. 1, p.44; Institute for Palestine Studies and Kuwait University, 1984

- Sarah Leibovitz-Dar. "Poisoned Land"; Maariv (Hebrew) November 10, 2005

- Tal, Alon, 1960- Space Matters: Historic Drivers and Turning Points In Israel's Open Space Protection Policy"; Israel Studies Volume 13, Number 1, Spring 2008, pp. 119—151

- Gideon Kressel. "Let Shepherding Endure: Applied Anthropology and the Preservation of a Cultural Tradition in Israel and the Middle East"; State University of New York Press (August 2003)

- Industrial Zone Israel Union for Environmental Defence

- Rebecca Manski. A Desert Mirage: The Rising Role of US Money in Negev Development Archived 2013-12-27 at the Wayback Machine; News from Within October/November 2006

- BUSTAN on the Blueprint Archived 2008-04-09 at the Wayback Machine; Excerpt of Rebecca Manski. "The Rising Role of American Money in Negev Development" Archived 2013-12-27 at the Wayback Machine; News from Within, October/November 2005

- "Middle East Report Online - Middle East Research and Information Project". Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Manski, Rebecca. "A Desert 'Mirage:' Privatizing Development Plans in the Negev/Naqab;" Bustan, 2005

- "Negev to Blossom Under JNF Blueprint". Jewish Journal. 4 November 2004. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- "When an 'Ecological' Community Is Not". Haaretz. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- The Bedouin in Israel: Demography Archived 2007-10-26 at the Wayback Machine Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1 July 1999

- One example: RCUV Press Release, 6 March 2003

- Seth J. Frantzman, Havatzelet Yahel, Ruth Kark Contested Indigeneity: The Development of an Indigenous Discourse on the Bedouin of the Negev, Israel Studies, Volume 17, Number 1, Spring 2012, pp. 78—104

- "Bedouin Join Aloni," Middle East International, No. 71 (May 1977), p. 21.

- "Bedouin Culture". Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Ḳrispil, Nissim (1985). A Bag of Plants (The Useful Plants of Israel) (Yalḳuṭ ha-tsemaḥim) (in Hebrew). Vol. 3 (Ṭ.-M.). Jerusalem: Cana Publishing House Ltd. pp. 734–741. ISBN 965-264-011-5. OCLC 959573975.

- Ḳrispil, Nissim (1985). A Bag of Plants (The Useful Plants of Israel) (Yalḳuṭ ha-tsemaḥim) (in Hebrew). Vol. 3 (Ṭ.-M.). Jerusalem: Cana Publishing House Ltd. p. 375. ISBN 965-264-011-5. OCLC 959573975.

- Bailey, Clinton; Danin, Avinoam (1981). "Bedouin Plant Utilization in Sinai and the Negev". Economic Botany. Springer on behalf of New York Botanical Garden Press. 35 (2): 158. doi:10.1007/BF02858682. JSTOR 4254272. S2CID 27839209.

- "Muslim Arab Bedouins serve as Jewish state's gatekeepers". Al Arabiya English. 24 April 2013.

- Geller, Randall S. (2012). "The Recruitment and Conscription of the Circassian Community into the Israel Defence Forces, 1948–58". Middle Eastern Studies. 48 (3): 387–399. doi:10.1080/00263206.2012.661722. S2CID 143772360.

- "The World Factbook". Archived from the original on 10 June 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- (in Hebrew) מישיבת הוועדה לענייני ביקורת המדינה

- Sales, Ben. Despite hardships, some Bedouins still feel obligation to serve Israel, JTA, August 20, 2012

- "Looking south". The Economist. 17 August 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- Steven Dinero (2004). "New Identity/Identities Formulation in a Post-Nomadic Community: The Case of the Bedouin of the Negev". National Identities. 6 (3): 261–275. doi:10.1080/1460894042000312349. S2CID 143809632.

- Kalman, Matthew (24 November 2006). "S.F.'s newest consul enjoys being Bedouin, proud to be Israeli / Ishmael Khaldi, who began life as a nomad (he was born in a small village close to Haifa), is first Muslim envoy to rise through ranks". SF Gate. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- San Francisco Chronicle, March 2009

- Cédric Parizot. "Gaza, Beersheba, Dhahriyya: Another Approach to the Negev Bedouin in the Israeli-Palestinian Space"; Bulletin du Centre de recherche français de Jérusalem, 2001.

- Mya Guarnieri, Where is the Bedouin Intifada? Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine, The Alternative Information Center (AIC), February 9, 2012

- Rhoda Kanaaneh. "Embattled Identities: Palestinian Soldiers in the Israeli Military"; Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 32, No. 3 (Spring, 2003), pp. 5-20

- Rubin, Lawrence (2017). "Islamic political activism among Israel's Negev Bedouin population". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 44 (3): 429–446. doi:10.1080/13530194.2016.1207503. S2CID 148142453.

- "Are Bedouin Palestinians?". Haaretz.

Further reading

- Abu-Saad, I. (2003). "Bedouin Arabs in Israel between the Hammer and the Anvil: Education as a Foundation for Survival and Development." In Champagne, D. and Abu-Saad, I. (eds) Future of Indigenous Peoples: Strategies for Survival and Development. Los Angeles: UCLA American Indian Studies Center, pp. 103–120.

- Abu-Rabiʻa, ʻAref (2001). Bedouin Century: Education and Development among the Negev Tribes in the Twentieth Century. New York. ISBN 978-1-57181-832-4. OCLC 47119256.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ben-David, Y. "The Bedouins in Israel — Land Conflicts and Social Issues." Jerusalem, Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, Jerusalem, (2004)

- Eran Razin and Harvey Lithwick."The Fiscal Capacity of the Bedouin Local Authorities in the Negev" and "Investment Opportunities in the Bedouin Urban Sector"; Ben Gurion University, 2000

- Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, People of Palestine (Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books, 2012), ASIN: B0094TU8VY

- Shamir, R. (1996) "Suspended in Space: Bedouins under the Law of Israel". Law & Society Review v30 (2), p. 231–257

- "Resolution adopted by the General Assembly -- without reference to a Main Committee (A/61/L.67 and Add.1)-- 61/295. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples"; UN, Sept. 13 2007

- Yocheved Miriam Russo. "The Battle to settle the Negev", The Jerusalem Post, June 16, 2005

- Khalidi, Walid (1992), All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948, Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies, ISBN 978-0-88728-224-9

- Bedouins in the State of Israel // The Knesset – Lexicon of Terms

External links

- Everything about the Negev Bedouin Way of Life, using two sources: Devillier Donegan Enterprises: Lawrence of Arabia; and Dr. Yosef Ben-David (Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies), The Bedouin in Israel, Israeli Foreign Ministry, July 1999.

- Negev Institute for Strategies of Peace and Development homepage

- Israel's Bedouin villages struggle for existence Archived 2009-11-24 at the Wayback Machine in the Harvard Law Record

- Israel's forgotten Bedouin, BBC News (audio)

- Joe Alon Bedouin cultural center and museum in Lahav Forest, homepage

- UNRECOGNIZED Photo Exhibition. Stories of unrecognized villages, by Tal Adler.

- The End of the Bedouin (2 August 2012), Counterpunch article by Jillian Kestler-D'Amours, reproduced from Le Monde Diplomatique (re-accessed August 2021)

- Lands of the Negev on YouTube, a short film presented by Israel Land Administration describing the challenges faced in providing land management and infrastructure to the Bedouins in Israel's southern Negev region

- Seth Frantzman, presentation on the topic of the contested indigeneity of the Negev Bedouin, Menachem Begin Heritage Center (video).

- EoZNews: The Bedouin problem in the Negev on YouTube, 19 February 2013

- Salman Abu Sitta; Rebecca Manski; Jonathan Cook; Yeela Ranaan; Irène Steinert; Gadi Algazi; Max Blumenthal (January 2011). "Ongoing Ethnic Cleansing: Judaizing the Naqab" (PDF). JNF EBook. JNF: Colonising Palestine Since 1901. JNF eBook. 'Ar'ara: Al-Beit: Association for the Defence of Human Rights in Israel. 3. Retrieved 14 August 2021 – via BDS movement website.

- Sasson, Aharon (2016) [2010]. Animal Husbandry in Ancient Israel. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-90351-1. Retrieved 14 August 2021. About the theory of uninterrupted nomadic lifestyle (without alternate periods of sedentary life) of the Bedouin in general, and of the Negev Bedouin in particular; and Arif el-Arif's theory of the origin of Negev Bedouin in the Hejaz and Sinai regions.