Behavioural change theories

Behavioural change theories are attempts to explain why human behaviours change. These theories cite environmental, personal, and behavioural characteristics as the major factors in behavioural determination. In recent years, there has been increased interest in the application of these theories in the areas of health, education, criminology, energy and international development with the hope that understanding behavioural change will improve the services offered in these areas. Some scholars have recently introduced a distinction between models of behavior and theories of change.[1] Whereas models of behavior are more diagnostic and geared towards understanding the psychological factors that explain or predict a specific behavior, theories of change are more process-oriented and generally aimed at changing a given behavior. Thus, from this perspective, understanding and changing behavior are two separate but complementary lines of scientific investigation.

General theories and models

Each behavioural change theory or model focuses on different factors in attempting to explain behaviour change. Of the many that exist, the most prevalent are learning theories, social cognitive theory, theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour, transtheoretical model of behavior change, the health action process approach, and the BJ Fogg model of behavior change. Research has also been conducted regarding specific elements of these theories, especially elements like self-efficacy that are common to several of the theories.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy[2] is an individual's impression of their own ability to perform a demanding or challenging task such as facing an exam or undergoing surgery. This impression is based upon factors like the individual's prior success in the task or in related tasks, the individual's physiological state, and outside sources of persuasion. Self-efficacy is thought to be predictive of the amount of effort an individual will expend in initiating and maintaining a behavioural change, so although self-efficacy is not a behavioural change theory per se, it is an important element of many of the theories, including the health belief model, the theory of planned behaviour and the health action process approach.

In 1977, Albert Bandura performed two experimental tests on the self-efficacy theory. The first study asked whether systematic desensitization could effect changes in avoidance behavior by improving people's expectations of their personal efficacy. The study found that "thorough extinction of anxiety arousal to visualized threats by desensitization treatment produced differential increases in self-efficacy. In accord with prediction, microanalysis of congruence between self-efficacy and performance showed self-efficacy to be a highly accurate predictor of degree of behavioral change following complete desensitization. The findings also lend support to the view that perceived self-efficacy mediates anxiety arousal." In the second experiment, Bandura examined the process of efficacy and behavioral change in individuals suffering from phobias. He found that self-efficacy was a useful predictor of the amount of behavioral improvement that phobics could gain through mastering threatening thoughts.[3]

Social learning and social cognitive theory

According to the social learning theory[4] (more recently expanded as social cognitive theory[5]), behavioural change is determined by environmental, personal, and behavioural elements. Each factor affects each of the others. For example, in congruence with the principles of self-efficacy, an individual's thoughts affect their behaviour and an individual's characteristics elicit certain responses from the social environment. Likewise, an individual's environment affects the development of personal characteristics as well as the person's behavior, and an individual's behaviour may change their environment as well as the way the individual thinks or feels. Social learning theory focuses on the reciprocal interactions between these factors, which are hypothesised to determine behavioral change.

Theory of reasoned action

The theory of reasoned action[6][7] assumes that individuals consider a behaviour's consequences before performing the particular behaviour. As a result, intention is an important factor in determining behaviour and behavioural change. According to Icek Ajzen, intentions develop from an individual's perception of a behaviour as positive or negative together with the individual's impression of the way their society perceives the same behaviour. Thus, personal attitude and social pressure shape intention, which is essential to performance of a behaviour and consequently behavioural change.

Theory of planned behaviour

In 1985, Ajzen expanded upon the theory of reasoned action, formulating the theory of planned behaviour,[8] which also emphasises the role of intention in behaviour performance but is intended to cover cases in which a person is not in control of all factors affecting the actual performance of a behaviour. As a result, the new theory states that the incidence of actual behaviour performance is proportional to the amount of control an individual possesses over the behaviour and the strength of the individual's intention in performing the behaviour. In his article, Further hypothesises that self-efficacy is important in determining the strength of the individual's intention to perform a behaviour. In 2010, Fishbein and Ajzen introduced the reasoned action approach, the successor of the theory of planned behaviour.

Transtheoretical or stages of change model

According to the transtheoretical model[9][10] of behavior change, also known as the stages of change model, states that there are five stages towards behavior change. The five stages, between which individuals may transition before achieving complete change, are precontemplation, contemplation, preparation for action, action, and maintenance. At the precontemplation stage, an individual may or may not be aware of a problem but has no thought of changing their behavior. From precontemplation to contemplation, the individual begins thinking about changing a certain behavior. During preparation, the individual begins his plans for change, and during the action stage the individual begins to exhibit new behavior consistently. An individual finally enters the maintenance stage once they exhibit the new behavior consistently for over six months. A problem faced with the stages of change model is that it is very easy for a person to enter the maintenance stage and then fall back into earlier stages. Factors that contribute to this decline include external factors such as weather or seasonal changes, and/or personal issues a person is dealing with.

Health action process approach

The health action process approach (HAPA)[11] is designed as a sequence of two continuous self-regulatory processes, a goal-setting phase (motivation) and a goal-pursuit phase (volition). The second phase is subdivided into a pre-action phase and an action phase. Motivational self-efficacy, outcome-expectancies and risk perceptions are assumed to be predictors of intentions. This is the motivational phase of the model. The predictive effect of motivational self-efficacy on behaviour is assumed to be mediated by recovery self-efficacy, and the effects of intentions are assumed to be mediated by planning. The latter processes refer to the volitional phase of the model.

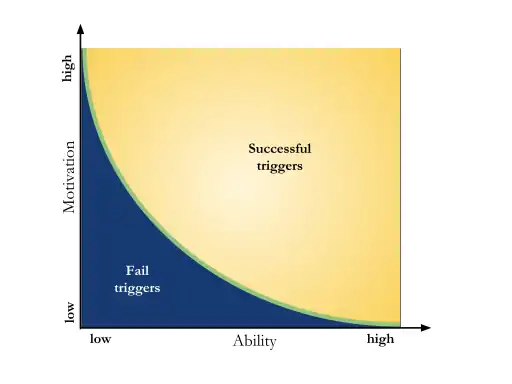

Fogg Behavior Model

The Fogg Behavior Model (FBM)[12] is a design behavior change model introduced by BJ Fogg. This model posits that behavior is composed of three different factors: motivation, ability and a prompt. Under the FBM, for any person (user) to succeed at behavior change needs to be motivated, have the ability to perform the behavior and needs a trigger to perform this behavior. The next are the definitions of each of the elements of the BFM:

Motivation

BJ Fogg does not provide a definition of motivation but instead defines different motivators:

- Pleasure/Pain: These motivators produce a response immediately and although powerful these are not ideal. Boosting motivation could be achieved by embodying pain or pleasure.

- Hope/fear: Both these motivators have a delayed response and are the anticipation of a future positive outcome (hope) or negative outcome (fear). As an example people joining a dating website hope to meet other people.

- Social acceptance/rejection: People are motivated by behaviors that increase or preserve their social acceptance.

Ability

This factor refers to the self-efficacy perception at performing a target behavior. Although low ability is undesirable it may be unavoidable: "We are fundamentally lazy," according to BJ Fogg. In such case behavior change is approached not through learning but instead by promoting target behaviors for which the user has a high ability. Additionally BJ Fogg listed several elements or dimensions that characterize high ability or simplicity of performing a behavior:

- Time: The user has the time to perform the target behavior or the time taken is very low.

- Money: The user has enough financial resources for pursuing the behavior. In some cases money can buy time.

- Physical effort: Target behaviors that require physical effort may not be simple enough to be performed.

- Brain cycles: Target behaviors that require high cognitive resources may not be simple hence undesirable for behavior change.

- Social deviance: These include behaviors that make the user socially deviant. These kind of behaviors are not simple.

- Non-routine: Any behavior that incurs disrupting a routine is considered not simple. Simple behaviors are usually part of routines and hence easy to follow.

Triggers

Triggers are reminders that may be explicit or implicit about the performance of a behavior. Examples of triggers can be alarms, text messages or advertisement, triggers are usually perceptual in nature but may also be intrinsic. One of the most important aspects of a trigger is timing as only certain times are best for triggering certain behaviors. As an example if a person is trying to go to the gym everyday, but only remembers about packing clothing once out of the house it is less likely that this person will head back home and pack. In contrast if an alarm sounds right before leaving the house reminding about packing clothing, this will take considerably less effort. Although the original article does not have any references for the reasoning or theories behind the model, some of its elements can be traced to social psychology theories, e.g., the motivation and ability factors and its success or failure are related to Self-efficacy.

Education

Behavioural change theories can be used as guides in developing effective teaching methods. Since the goal of much education is behavioural change, the understanding of behaviour afforded by behavioural change theories provides insight into the formulation of effective teaching methods that tap into the mechanisms of behavioural change. In an era when education programs strive to reach large audiences with varying socioeconomic statuses, the designers of such programs increasingly strive to understand the reasons behind behavioural change in order to understand universal characteristics that may be crucial to program design.

In fact, some of the theories, like the social learning theory and theory of planned behaviour, were developed as attempts to improve health education. Because these theories address the interaction between individuals and their environments, they can provide insight into the effectiveness of education programs given a specific set of predetermined conditions, like the social context in which a program will be initiated. Although health education is still the area in which behavioural change theories are most often applied, theories like the stages of change model have begun to be applied in other areas like employee training and developing systems of higher education.

Criminology

Empirical studies in criminology support behavioural change theories.[13] At the same time, the general theories of behavioural change suggest possible explanations to criminal behaviour and methods of correcting deviant behaviour. Since deviant behaviour correction entails behavioural change, understanding of behavioural change can facilitate the adoption of effective correctional methods in policy-making. For example, the understanding that deviant behaviour like stealing may be learned behaviour resulting from reinforcers like hunger satisfaction that are unrelated to criminal behaviour can aid the development of social controls that address this underlying issue rather than merely the resultant behaviour.

Specific theories that have been applied to criminology include the social learning and differential association theories. Social learning theory's element of interaction between an individual and their environment explains the development of deviant behaviour as a function of an individual's exposure to a certain behaviour and their acquaintances, who can reinforce either socially acceptable or socially unacceptable behaviour. Differential association theory, originally formulated by Edwin Sutherland, is a popular, related theoretical explanation of criminal behaviour that applies learning theory concepts and asserts that deviant behaviour is learned behaviour.

Energy

Recent years have seen an increased interest in energy consumption reduction based on behavioural change, be it for reasons of climate change mitigation or energy security. The application of behavioural change theories in the field of energy consumption behaviour yields interesting insights. For example, it supports criticism of a too narrow focus on individual behaviour and a broadening to include social interaction, lifestyles, norms and values as well as technologies and policies—all enabling or constraining behavioural change.[14]

Methods

Besides the models and theories of behavior change there are methods for promoting behavior change. Among them one of the most widely used is Tailoring or personalization.

Tailoring

Tailoring refers to methods for personalizing communications intended to generate higher behavior change than non personalized ones.[15] There are two main claims for why tailoring works: Tailoring may improve preconditions for message processing and tailoring may improve impact by altering starting behavioral determinants of goal outcomes. The different message processing mechanisms can be summarized into: Attention, Effortful processing, Emotional processing and self-reference.

- Attention: Tailored messages are more likely to be read and remembered

- Effortful processing: Tailored messages elicit careful consideration of persuasive arguments and more systematic utilization of the receivers own schemas and memories. This could also turn out damaging because this careful consideration does increase counterarguing, evaluations of credibility and other processes that lessens message effects.

- Peripheral emotion/processing: tailoring could be used to create an emotional response such as fear, hope or anxiety. Since positive emotions tend to reduce effortful processing and negative emotions enhance it, emotion arousal could elicit varying cognitive processing.

- Self-reference: This mechanism promotes the comparison between actual and ideal behaviors and reflection.

Behavioral determinants of goal outcomes are the different psychological and social constructs that have a direct influence on behavior. The three most used mediators in tailoring are attitude, perception of performance and self efficacy. Although results are largely positive they are not consistent and more research on the elements that make tailoring work is necessary.

Objections

Behavioural change theories are not universally accepted. Criticisms include the theories' emphases on individual behaviour and a general disregard for the influence of environmental factors on behaviour. In addition, as some theories were formulated as guides to understanding behaviour while others were designed as frameworks for behavioural interventions, the theories' purposes are not consistent. Such criticism illuminates the strengths and weaknesses of the theories, showing that there is room for further research into behavioural change theories.

See also

References

- van der Linden, S. (2013). "A Response to Dolan. In A. Oliver (Ed.)" (PDF). pp. 209–2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-10. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- Bandura Albert (1977-03-01). "Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change". Psychological Review. 84 (2): 191–215. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.315.4567. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. ISSN 1939-1471. PMID 847061.

- Bandura, Albert; Adams, Nancy E. (1977-12-01). "Analysis of self-efficacy theory of behavioral change". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1 (4): 287–310. doi:10.1007/BF01663995. ISSN 1573-2819. S2CID 206801475.

- "Social learning theory". APA PsycNET. 1977-01-01.

- Lange, Paul A. M. Van; Kruglanski, Arie W.; Higgins, E. Tory (2011-08-31). Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Collection: Volumes 1 & 2. SAGE. ISBN 9781473971370.

- Ajzen, I (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall.

- Fishbein, M (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior. Addison-Wesley.

- Ajzen, Icek (1985-01-01). "From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior". In Kuhl, PD Dr Julius; Beckmann, Dr Jürgen (eds.). Action Control. SSSP Springer Series in Social Psychology. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 11–39. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2. ISBN 9783642697487. S2CID 61324398.

- Prochaska, James O.; Velicer, Wayne F. (1997-09-01). "The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change". American Journal of Health Promotion. 12 (1): 38–48. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. ISSN 0890-1171. PMID 10170434. S2CID 46879746.

- Prochaska, J. O.; DiClemente, C. C. (1983-06-01). "Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 51 (3): 390–395. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.51.3.390. ISSN 0022-006X. PMID 6863699. S2CID 11164325.

- Schwarzer, Ralf (2008-01-01). "Modeling Health Behavior Change: How to Predict and Modify the Adoption and Maintenance of Health Behaviors". Applied Psychology. 57 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00325.x. ISSN 1464-0597. S2CID 36178352.

- Fogg, BJ (2009-01-01). "A behavior model for persuasive design". Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology. Persuasive '09. New York, NY, US: ACM. pp. 40:1–40:7. doi:10.1145/1541948.1541999. ISBN 9781605583761. S2CID 1659386.

- Whitehead, Dean (2001). "Health education, behavioural change and social psychology: nursing's contribution to health promotion?". Journal of Advanced Nursing. 34 (6): 822–832. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01813.x. ISSN 1365-2648. PMID 11422553.

- Shove, Elizabeth; Pantzar, Mika; Watson, Matt (2012). The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and how it Changes. SAGE. p. 208. ISBN 978-1446258170.

- Hawkins, Robert P.; Kreuter, Matthew; Resnicow, Kenneth; Fishbein, Martin; Dijkstra, Arie (2008-06-01). "Understanding tailoring in communicating about health". Health Education Research. 23 (3): 454–466. doi:10.1093/her/cyn004. ISSN 0268-1153. PMC 3171505. PMID 18349033.