Beijing Daily

Beijing Daily (Chinese: 北京日报; pinyin: Běijīng rìbào) is the official newspaper of the Beijing municipal committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Founded on October 1, 1952, it has since 2000 been owned by the Beijing Daily Group, which also runs eight other newspapers. It has a circulation of about 400,000 per day, making it one of the most widely circulated newspapers in the city.[1]

.jpg.webp) Beijing Daily headquarters | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Owner(s) | Beijing Daily Group |

| Founded | October 1, 1952 |

| Political alignment | Chinese Communist Party |

| Language | Chinese (simplified) |

| Headquarters | Dongcheng District, Beijing |

| Circulation | 400,000 daily |

| Website | bjrb.bjd.com.cn |

History

When the People's Liberation Army occupied Beijing, all the Kuomintang and private newspapers were forced to close or taken over by the Communist authorities.[2] The initial organ of the Beijing Party Committee was Beiping Jiefang Bao (Beiping Liberation News), but this soon ceased publication because many journalists had to move southward with the army. The committee felt it was necessary to create a new party newspaper, so preparatory work started in March 1951. In 1952, Fan Jin came from Tianjin, and was appointed as the director of the Beijing Daily preparatory group. On October 1 of the same year, publication of Beijing Daily started.[3]

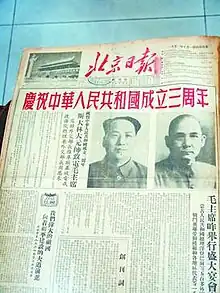

The paper's header was inscribed by Mao Zedong, who wrote the title with his calligraphy for the masthead in September 1952 when requested to do so by the editors, which was considered a tremendous honor.[4] The inaugural issue was released on 1 October 1952, to correspond with the third anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China.[2] It was drafted by Liao Mosha, then Head of the Propaganda Department of the CCP's Beijing committee, and edited by Mayor Peng Zhen. When its publication started, it lacked articles to receive, many contents were identical to those in People's Daily. At a conference held on October 16, Peng Zhen advocated to publish shorter and more local articles. Shortly afterwards, a labor strike broke out, Beijing Daily fought a successful propaganda campaign. From then, the newspaper became popular among workers in Beijing.[5] As with other Chinese publications of the time, the layout of Beijing Daily was heavily influenced by the Soviet press, with simple language used to accommodate the lack of education among the populace. Additionally, the paper contained many visual representations, with photographs, cartoons, lianhuanhua and other depictions, and several established artists such as Li Hua would provide artwork for the paper.[6]

During the Three Red Banners movement and the Great Leap Forward, Beijing Daily initially reported enthusiastically on Mao's initiatives, to the point that senior municipal party officials reprimanded the newspaper for highly exaggerated reports such as one that claimed the system of backyard furnaces in Chaoyan District had produced more steel than two of the city's metallurgical plants.[7] From 1963 to 1966, the newspaper did not cooperate with the Gang of Four. It refused to reprint Yao Wenyuan's criticism of Hai Rui Dismissed from Office.[3] For that reason it was criticized as an "anti-party instrument" by the Guangming Daily and People's Liberation Army Daily on May 8, 1966.[8]: 150 The North China Bureau of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party sent a work group to the newspaper office, reorganized the editorial board. On September 3, 1966, it was forced to cease publication. On March 17, 1967, the headquarters of PLA Beijing garrison declared military control of the newspaper office, many staff members were criticized and denounced. In April of the same year its publication resumed.[8]: 151 During the Cultural Revolution, Beijing Daily, along with other local newspapers, followed the leftist policy of Mao, made propaganda reports on "typical paths" of socialist construction.[8]: 208–211

In the following years, the Military Control Commission, Military Propaganda Team, Labor Propaganda Team were removed. In August 1972, a new leading board was formed. After 1976, they began to deal with the remaining problems of Cultural Revolution.[8]: 151 On January 1, 1991, laser typesetting system was first introduced. In January 2001, they built a new printing center, the main factory building has an area of 30000 square meters. In October 2012, a new news editing center of 40000 square meters architectural area was built.[9]

Content

The newspaper is now published in 16 pages. It reports on international, domestic and local news as well as economy, society, culture and sports in Beijing. There are 4 special issues, 6 supplements published every week.[1] Each page contains 10 to 30 reports. Sometimes they use magnified photographs, lines, entoilages and lace to increase beauty grade.[10]

In 1958, the daily continually published more than 10 editorials on mechanization and semi-mechanization. The same year, a special column "Thought Discussion" was created (inspired by China Youth Daily), and attracted many manuscripts received from the folks. Liu Shaoqi once participated in a discussion on "Should the communists have individual voluntary?", his words was sorted out in an article published by Beijing Daily.[5] In the atmosphere of Great Leap Forward, it also falsely reported many cases of ever-higher grain production. For example, there was a report stating that a production brigade could raise the rice yield to 5000 - 6000 jin per mu.[3] In 1961, the newspaper office and the department of village affairs of Beijing committee formed a survey group to investigate the villager's views about collective dining rooms. They found out that most villagers are opposed to eat in those rooms, and published a report about that.[3]

As an official media, Beijing Daily has propagated many stories of "advanced individuals" and "advanced collectivities". Among them are: tiler Zhang Baifa, woodcutter's crew leader Li Ruihuan, fitter Ni Zhifu, hygiene worker Shi Chuanxiang, Tianqiao Department Store, Shijingshan Steel Corporation Dolomite Workshop, Pack Basket Store at Zhoukoudian Supply & Marketing Cooperative, Nanhanji Production Brigade, salesman Zhang Binggui, Great Wall Raincoat Company manager Zhang Jieshi and Big Bowl Tea Trade Group.[11] From January to March 1971, it continually published hundreds of stories, quotations, and photographs of Wang Fuguo, a Daxing County party branch secretary. These reports strongly exaggerated his "routes struggle" consciousness.[8] In September 1973, it published a letter from a primary school student who had conflicts with his teacher. The letter was praised by Gang of Four, and was described as "introducing an important question about education reform".[8]: 212

The Theory Weekly is published every Monday, comprising four pages. Its main readers are members of party and government organizations. About a third of the articles are less than 1000 words. Three fifths of the theory propaganda articles appear on the front page of the weekly.[12]: 150–153 About half of the articles are interpretations to CCP files or lectures given by party leaders. 1/4 of articles discuss social problems and social thoughts.[12]: 156

References

- "北京日报报业集团简介". Beijing Daily Group. Archived from the original on 2014-08-19. Retrieved 2014-09-01.

- Hung 2014, p. 344.

- 周游 (1983). "坚持唯物主义,坚持实事求是--纪念《北京日报》创刊三十周年". 新闻研究资料 (1): 59–68. Retrieved 2014-09-03.

- Hung 2014, p. 342.

- Fan Jin (1983). "怀念与敬意--回忆市委领导对《北京日报》的关怀". 新闻研究资料 (1): 48–58. Retrieved 2014-09-02.

- Hung 2014, pp. 347–348.

- Hung 2014, pp. 360.

- 北京市地方志编纂委员会, ed. (2006). 北京志 新闻出版广播电视卷 报业·通讯社志 (in Chinese). Beijing Publishing House. ISBN 7-200-06348-7.

- "从一张报到一个集团". Beijing Daily. Archived from the original on 2014-09-07. Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- 民子 (1992). "打破常规求版式—谈北京日报版面编排技巧". 中国记者 (7): 16–18. ISSN 1003-1146. Retrieved 2014-09-06.

- 当代中国的新闻事业 (in Chinese). Beijing: 当代中国出版社. 2009. p. 351. ISBN 978-7-80170-845-8.

- 魏彧 (2010). 党报与先进文化 (in Chinese). Tianjin People's Publishing House. ISBN 978-7-201-06416-1.

Bibliography

- Hung, Chang-tai (April 2014). "Inside a Chinese Communist Municipal Newspaper: Purges at the Beijing Daily". Journal of Contemporary History. 49 (2): 341–365. doi:10.1177/0022009413515534. ISSN 0022-0094. S2CID 143435434.