Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goal was to preserve Chinese communism by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society. Though it failed to achieve its main goals, the Revolution marked the effective, ultimately permanent return of Mao to the center of power. This had come after a period of relative abstention for Mao, who had been sidelined by the more moderate Seven Thousand Cadres Conference in the aftermath of the Great Leap Forward and the following Great Chinese Famine, which occurred while he was still chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Propaganda poster depicting Mao Zedong, above a group of soldiers from the People's Liberation Army. The caption reads, "The Chinese People's Liberation Army is the great school of Mao Zedong Thought". | |

| Duration | May 16, 1966 – October 6, 1976 (10 years and 143 days) |

|---|---|

| Location | China |

| Motive | Preservation of communism by purging capitalist and traditional elements, and power struggle between Maoists and pragmatists. |

| Organized by | Chinese Communist Party Politburo |

| Outcome | Economic activity impaired, historical and cultural material destroyed. |

| Deaths | Estimates vary from hundreds of thousands to millions (see § Death toll) |

| Property damage | Cemetery of Confucius, Temple of Heaven, Ming Tombs |

| Arrests | Jiang Qing, Zhang Chunqiao, Yao Wenyuan, and Wang Hongwen |

| Cultural Revolution | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 文化大革命 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Great Cultural Revolution" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Formal name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 无产阶级文化大革命 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 無產階級文化大革命 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of the People's Republic of China |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| History of |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Political revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

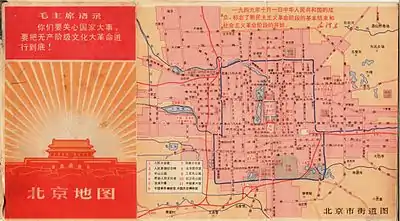

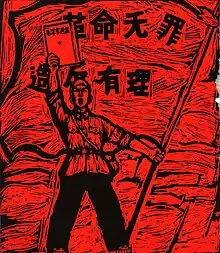

Launching the movement in May 1966 with the help of the Cultural Revolution Group, Mao charged that bourgeois elements had infiltrated the government and society with the aim of restoring capitalism. Mao called on young people to "bombard the headquarters", and proclaimed that "to rebel is justified". Many young people, mainly students, responded by forming cadres of Red Guards throughout the country. A selection of Mao's sayings were compiled into the Little Red Book, which became revered within his cult of personality. Public "struggle sessions" were regularly organized, targeting those deemed to be capitalists, reactionaries, or revisionists. In 1967, emboldened radicals began seizing power from local governments and party branches, establishing new "revolutionary committees" in their stead. These committees often split into rival factions, precipitating armed clashes among the radicals, which only came to an end when the People's Liberation Army (PLA) was ordered to intervene. Lin Biao, a PLA marshal, had quickly ascended to become Mao's heir apparent after the PLA intervention, only to be accused of planning and executing a botched coup against Mao. Lin fled the country, but died when his plane crashed. The Gang of Four took center stage in 1972, and the Revolution would ultimately go on until Mao's death in 1976, followed by the arrest of the Gang of Four.

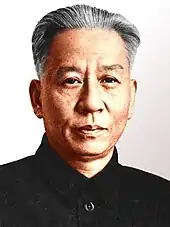

The Cultural Revolution was characterized by violence and chaos at every level of Chinese society. Estimates of the death toll vary widely, typically ranging from 500,000 to 2,000,000.[1][2] Mass upheaval began in Beijing with the Red August of 1966, and subsequently spread across the country, often resulting in widespread violence. This period saw numerous regional atrocities, including a massacre in Guangxi that included acts of cannibalism,[3][4] as well as incidents in Inner Mongolia, Guangdong, Yunnan, and Hunan. Red Guards, primarily consisting of university students, endeavored to destroy the "Four Olds": old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits. This often took the form of destroying historical artifacts, ransacking cultural and religious sites, and targeting other citizens deemed to be representative of the Four Olds. The 1975 Banqiao Dam failure, one of the world's greatest technological catastrophes, also occurred during the Cultural Revolution. Meanwhile, tens of millions were persecuted, including senior officials: most notably, president Liu Shaoqi, as well as Deng Xiaoping, Peng Dehuai, and He Long, were purged or exiled. Millions were formally accused of being members of the Five Black Categories, and suffered public humiliation, imprisonment, torture, hard labor, seizure of property, and sometimes execution or harassment into suicide. Intellectuals were considered to be the "Stinking Old Ninth", and became widely persecuted, with scholars and scientists such as Lao She, Fu Lei, Yao Tongbin, and Zhao Jiuzhang killed or forced to commit suicide. The country's schools and universities were closed, and the National College Entrance Examination were cancelled. Over 10 million youth from urban areas were relocated by the Down to the Countryside Movement policy.

In December 1978, Deng Xiaoping became the new paramount leader of China, replacing Mao's successor Hua Guofeng; he and his allies introduced the Boluan Fanzheng program, which gradually dismantled policies associated with the Cultural Revolution, [5][6] and embarked on a massive economic liberalization program program for the country. In 1981, the Party publicly acknowledged numerous failures of the Cultural Revolution, and moreover declared that it was wrong, and "responsible for the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the people, the country, and the party since the founding of the People's Republic."[7][8][9] In contemporary China, with the Cultural Revolution having directly affected so many individuals across different areas of society, memories and perspectives are varied and complex. It is often referred to in retrospect as the "ten years of chaos" (十年动乱; shí nián dòngluàn or 十年浩劫; shí nián hàojié).[10]

Background

Great Leap Forward

.jpg.webp)

In 1958, after China's first five-year plan, Mao called for "grassroots socialism" in order to accelerate his plans for turning China into a modern industrialized state. In this spirit, Mao launched the Great Leap Forward, established people's communes in the countryside, and began the mass mobilization of the people into collectives. Many communities were assigned production of a single commodity—steel. Mao vowed to increase agricultural production to twice that of 1957 levels.[11]

The Great Leap was an economic failure. Many uneducated farmers were pulled from farming and harvesting and instead instructed to produce steel on a massive scale, partially relying on backyard furnaces to achieve the production targets set by local cadres. The steel produced was of low quality and mostly useless. The Great Leap reduced harvest sizes and led to a decline in the production of most goods except substandard pig iron and steel. Furthermore, local authorities frequently exaggerated production numbers, hiding and intensifying the problem for several years.[12][13]: 25–30

In the meantime, chaos in the collectives, bad weather, and exports of food necessary to secure hard currency resulted in the Great Chinese Famine. Food was in desperate shortage, and production fell dramatically. The famine caused the deaths of more than 30 million people, particularly in the more impoverished inland regions.[14]

The Great Leap's failure reduced Mao's prestige within the CCP. Forced to take responsibility, in 1959, Mao resigned as President, the de jure head of state, and was succeeded by Liu Shaoqi, while Mao remained as Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party and Commander-in-chief. In July, senior Party leaders convened at the Lushan conference. There, Marshal Peng Dehuai criticized Great Leap policies in a private letter to Mao, writing that it was plagued by mismanagement and cautioning against elevating political dogma over the laws of economics.[12]

Despite the moderate tone of Peng's letter, Mao took it as a personal attack against his leadership.[13]: 55 Following the Conference, Mao had Peng removed from his posts, and accused him of being a "right-opportunist". Peng was replaced by Lin Biao, another revolutionary army general who became a more staunch Mao supporter later in his career. While the Lushan Conference served as a death knell for Peng, Mao's most vocal critic, it led to a shift of power to moderates led by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, who took effective control of the economy following 1959.[12]

By the early 1960s, many of the Great Leap's economic policies were reversed by initiatives spearheaded by Liu, Deng, and Premier Zhou Enlai. This moderate group of pragmatists were unenthusiastic about Mao's utopian visions. By 1962, while Zhou, Liu and Deng managed affairs of state and the economy, Mao had effectively withdrawn from economic decision-making, and focused much of his time on further contemplating his contributions to Marxist–Leninist social theory, including the idea of "continuous revolution".[13]: 55

Impact of international tensions and anti-revisionism

In the early 1950s, the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union were the two largest communist states in the world. Although initially they had been mutually supportive, disagreements arose after the death of Joseph Stalin and the rise of Nikita Khrushchev to power in the Soviet Union. In 1956, Khrushchev denounced Stalin and his policies, and began implementing post-Stalinist economic reforms. Mao and many other members of the CCP opposed these changes, believing that they would have negative repercussions for the worldwide communist movement, among many of whom Stalin was still viewed as a hero.[15]: 4–7

Mao believed that Khrushchev did not adhere to Marxism–Leninism, but was instead a revisionist, altering his policies from basic Marxist–Leninist concepts, something Mao feared would allow capitalists to regain control of the USSR. Relations between the two governments soured. The USSR refused to support China's case for joining the United Nations and reneged on its pledge to supply China with a nuclear weapon.[15]: 4–7

Mao went on to publicly denounce revisionism in April 1960. Without pointing fingers at the Soviet Union, Mao criticized its ideological ally in the Balkans, the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. In turn, the USSR criticized China's ally in the Balkans, the Party of Labour of Albania.[15]: 7 In 1963, the CCP began to denounce the Soviet Union openly, publishing nine polemics against its perceived revisionism, with one of them being titled On Khrushchev's Phoney Communism and Historical Lessons for the World, in which Mao charged that Khrushchev was not only a revisionist but also increased the danger of capitalist restoration.[15]: 7 Khrushchev's downfall from an internal coup d'état in 1964 also contributed to Mao's fears of his own political vulnerability, mainly because of his declining prestige among his colleagues after the Great Leap Forward.[15]: 7

Other Soviet actions increased concerns about potential fifth columnists in China.[16]: 141 As a result of the tensions following the Sino-Soviet split, Soviet leaders had authorized radio broadcasts into China stating that the Soviet Union would assist "genuine communists" who overthrew Mao and his "erroneous course."[16]: 141 Chinese leadership also feared the increasing military conflict between the United States and the North Vietnamese troops that China supported would lead to the United States seeking out potential Chinese traitors.[16]: 141 These international tensions shaped the inception and course of the Cultural Revolution.[16]: 14

Precursor

In 1963, Mao launched the Socialist Education Movement, which is regarded as the precursor of the Cultural Revolution.[17] Mao had set the scene for the Cultural Revolution by "cleansing" powerful officials of questionable loyalty who were based in Beijing. His approach was less than transparent, achieving this purge through newspaper articles, internal meetings, and by skillfully employing his network of political allies.[17]

In late 1959, historian and deputy mayor of Beijing Wu Han published a historical drama entitled Hai Rui Dismissed from Office. In the play, an honest civil servant, Hai Rui, is dismissed by a corrupt emperor. While Mao initially praised the play, in February 1965, he secretly commissioned his wife Jiang Qing and Shanghai propagandist Yao Wenyuan to publish an article criticizing it.[15]: 15–18 Yao described the play as an allegory attacking Mao; that is, Mao was the corrupt emperor, and Peng Dehuai was the honest civil servant.[15]: 16

Yao's article put Beijing mayor Peng Zhen[note 1] on the defensive. Peng, a powerful official and Wu Han's direct superior, was the head of the "Five Man Group", a committee commissioned by Mao to study the potential for a cultural revolution. Peng Zhen, aware that he would be implicated if Wu indeed wrote an "anti-Mao" play, wished to contain Yao's influence. Yao's article was initially only published in select local newspapers. Peng forbade its publication in the nationally distributed People's Daily and other major newspapers under his control, instructing them to write exclusively about "academic discussion," and not pay heed to Yao's petty politics.[15]: 14–19 While the "literary battle" against Peng raged, Mao fired Yang Shangkun—director of the party's General Office, an organ that controlled internal communications—on a series of unsubstantiated charges, installing in his stead staunch loyalist Wang Dongxing, head of Mao's security detail. Yang's dismissal likely emboldened Mao's allies to move against their factional rivals.[15]: 14–19

On 12 February 1966, the "Five Man Group" issued a report known as the February Outline. The Outline as sanctioned by the party center defined Hai Rui as a constructive academic discussion and aimed to distance Peng Zhen formally from any political implications. However, Jiang Qing and Yao Wenyuan continued their denunciation of Wu Han and Peng Zhen. Meanwhile, Mao also sacked Propaganda Department director Lu Dingyi, a Peng Zhen ally.[15]: 20–27

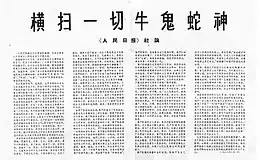

Lu's removal gave Maoists unrestricted access to the press. Mao would deliver his final blow to Peng Zhen at a high-profile Politburo meeting through loyalists Kang Sheng and Chen Boda. They accused Peng Zhen of opposing Mao, labeled the February Outline "evidence of Peng Zhen's revisionism", and grouped him with three other disgraced officials as part of the "Peng-Luo-Lu-Yang Anti-Party Clique."[15]: 20–27 On 16 May, the Politburo formalized the decisions by releasing an official document condemning Peng Zhen and his "anti-party allies" in the strongest terms, disbanding his "Five Man Group", and replacing it with the Maoist Cultural Revolution Group (CRG).[15]: 27–35

1966: Outbreak

The history of the Cultural Revolution can generally be categorized into two main periods: (1) spring 1966 to summer 1968 (when most of the key events took place), and (2) a tailing period that lasted until fall 1976.[18] The early phase of the Cultural Revolution was characterized by mass movement and political pluralization.[18] Virtually anyone could create a political organization, with or without party approval.[18] Known as Red Guards, these organizations originally arose in schools and universities and later arose in factories and other institutions.[18] After 1968, most of these organizations ceased to exist and their legacies were a topic of intense controversy in the latter part of the Cultural Revolution.[18]

Notification

In May 1966, an expanded session of the Politburo was called in Beijing. The conference was laden with Maoist political rhetoric on class struggle and filled with meticulously prepared 'indictments' on the recently ousted leaders such as Peng Zhen and Luo Ruiqing. One of these documents, distributed on 16 May, was prepared with Mao's personal supervision and was particularly damning:[15]: 39-40

Those representatives of the bourgeoisie who have sneaked into the Party, the government, the army, and various spheres of culture are a bunch of counter-revolutionary revisionists. Once conditions are ripe, they will seize political power and turn the dictatorship of the proletariat into a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. Some of them we have already seen through; others we have not. Some are still trusted by us and are being trained as our successors, persons like Khrushchev for example, who are still nestling beside us.[15]: 47

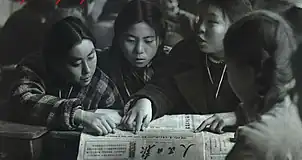

Later known as the "16 May Notification", this document summarized Mao's ideological justification for the Cultural Revolution.[15]: 40 Initially a secret document only distributed among high-ranking party members, it would later be declassified and published in People's Daily on 17 May 1967.[15]: 41 Effectively it implied that there were enemies of the Communist cause within the Party itself: class enemies who "wave the red flag to oppose the red flag." The only way to identify these people was through "the telescope and microscope of Mao Zedong Thought."[15]: 46 While the party leadership was relatively united in approving the general direction of Mao's agenda, many Politburo members were not especially enthusiastic, or simply confused about the direction of the movement.[19]: 13 The charges against esteemed party leaders like Peng Zhen rang alarm bells in China's intellectual community and among the eight non-Communist parties.[15]: 41

Mass rallies (May–June)

After the purge of Peng Zhen, the Beijing Party Committee had effectively ceased to function, paving the way for disorder in the capital. On 25 May, under the guidance of Cao Yi'ou—wife of Mao loyalist Kang Sheng—Nie Yuanzi, a philosophy lecturer at Peking University, authored a big-character poster along with other leftists and posted it to a public bulletin. Nie attacked the university's party administration and its leader Lu Ping.[15]: 56–58 Nie insinuated that the university leadership, much like Peng Zhen, were trying to contain revolutionary fervor in a "sinister" attempt to oppose the party and advance revisionism.[15]: 56–58

Mao promptly endorsed Nie's poster as "the first Marxist big-character poster in China". Having been approved by Mao, the poster had a ripple effect across educational institutions in China. Students began to revolt against their respective schools' party establishment. Classes were promptly cancelled in Beijing primary and secondary schools, followed by a decision on 13 June to expand the class suspension nationwide.[15]: 59–61 By early June, throngs of young demonstrators lined the capital's major thoroughfares holding giant portraits of Mao, beating drums, and shouting slogans against his perceived enemies.[15]: 59–61

When the dismissal of Peng Zhen and the municipal party leadership became public in early June, widespread confusion ensued. The public and foreign missions were kept in the dark on the reason for Peng Zhen's ousting.[15]: 62–64 Even the top Party leadership was caught off guard by the sudden anti-establishment wave of protest and struggled with what to do next.[15]: 62–64 After seeking Mao's guidance in Hangzhou, Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping decided to send in 'work teams'—effectively 'ideological guidance' squads of cadres—to the city's schools and People's Daily to restore some semblance of order and re-establish party control.[15]: 62–64

The work teams were hastily dispatched and had a poor understanding of student sentiment. Unlike the political movement of the 1950s that squarely targeted intellectuals, the new movement was focused on established party cadres, many of whom were part of the work teams. As a result, the work teams came under increasing suspicion for being yet another group aimed at thwarting revolutionary fervor.[15]: 71 The party leadership subsequently became divided over whether or not work teams should remain in place. Liu Shaoqi insisted on continuing work-team involvement and suppressing the movement's most radical elements, fearing that the movement would spin out of control.[15]: 75

Bombard the Headquarters (July)

On 16 July, Mao, now 72 years old, took to the Yangtze in Wuhan with a press juncket, in tow, in what became an iconic "swim across the Yangtze" to demonstrate his battle-readiness. He subsequently returned to Beijing on a mission to criticize the party leadership for its handling of the work-teams issue. Mao accused the work teams of undermining the student movement, calling for their full withdrawal on July 24. Several days later a rally was held at the Great Hall of the People to announce the decision and set the new tone of the movement to university and high school teachers and students. At the rally, Party leaders told the masses assembled to 'not be afraid' and bravely take charge of the movement themselves, free of Party interference.[15]: 84

The work-teams issue marked a decisive defeat for President Liu Shaoqi politically; it also signaled that disagreement over how to handle the unfolding events of the Cultural Revolution would break Mao from the established party leadership irreversibly. On 1 August, the Eleventh Plenum of the 8th Central Committee was hastily convened to advance Mao's now decidedly radical agenda. At the plenum, Mao showed outright disdain for Liu, repeatedly interrupting Liu as he delivered his opening day speech.[15]: 94

For several days, Mao repeatedly insinuated that the party's leadership had contravened his revolutionary vision. Mao's line of thinking received a lukewarm reception from the conference attendees. Sensing that the largely obstructive party elite was unwilling to embrace his revolutionary ideology on a full scale, Mao went on the offensive.

On July 28, Red Guard representatives wrote to Mao, calling for rebellion and upheaval to safeguard the revolution. Mao then responded to the letters by writing his own big-character poster entitled Bombard the Headquarters, rallying people to target the "command centre (i.e., Headquarters) of counterrevolution." Mao wrote that despite having undergone a communist revolution, a "bourgeois" elite was still thriving in "positions of authority" in the government and Communist Party.[11]

Although no names were mentioned, this provocative statement by Mao has been interpreted as a direct indictment of the party establishment under Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping—the purported "bourgeois headquarters" of China. The personnel changes at the Plenum reflected a radical re-design of the party's hierarchy to suit this new ideological landscape. Liu and Deng kept their seats on the Politburo Standing Committee but were in fact sidelined from day-to-day party affairs. Lin Biao was elevated to become the CCP's number-two figure; Liu Shaoqi's rank went from second to eighth and was no longer Mao's heir apparent.[11]

Coinciding with the top leadership being thrown out of positions of power was the thorough undoing of the entire national bureaucracy of the Communist Party. The extensive Organization Department, in charge of party personnel, virtually ceased to exist. The Cultural Revolution Group (CRG), Mao's ideological 'Praetorian Guard', was catapulted to prominence to propagate his ideology and rally popular support. The top officials in the Propaganda Department were sacked, with many of its functions folding into the CRG.[15]: 96

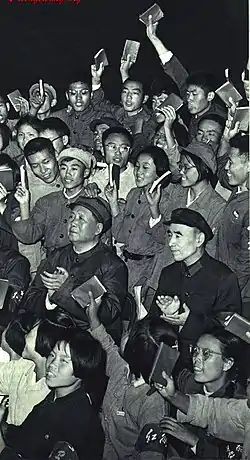

Red August and the Sixteen Points

The Little Red Book was the mechanism that led the Red Guards to commit to their objective as the future for China. These quotes directly from Mao led to other actions by the Red Guards in the views of other Maoist leaders,[15]: 107 and by December 1967, 350 million copies of the book had been printed.[21]: 61–64 Quotations in the Little Red Book that the Red Guards would later follow as a guide, provided by Mao, included the famous "Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun." The passage goes on:

Revolutionary war is an antitoxin which not only eliminates the enemy's poison but also purges us of our filth. Every just, revolutionary war is endowed with tremendous power and can transform many things or clear the way for their transformation. The Sino-Japanese war will transform both China and Japan; Provided China perseveres in the War of Resistance and in the united front, the old Japan will surely be transformed into a new Japan and the old China into a new China, and people and everything else in both China and Japan will be transformed during and after the war. The world is yours, as well as ours, but in the last analysis, it is yours. You young people, full of vigor and vitality, are in the bloom of life, like the sun at eight or nine in the morning. Our hope is placed on you ... The world belongs to you. China's future belongs to you.

During the Red August of Beijing, on August 8, 1966, the party's General Committee passed its "Decision Concerning the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution," later to be known as the "Sixteen Points."[22] This decision defined the Cultural Revolution as "a great revolution that touches people to their very souls and constitutes a deeper and more extensive stage in the development of the socialist revolution in our country:"[23]

Although the bourgeoisie has been overthrown, it is still trying to use the old ideas, culture, customs, and habits of the exploiting classes to corrupt the masses, capture their minds, and stage a comeback. The proletariat must do just the opposite: It must meet head-on every challenge of the bourgeoisie ... to change the outlook of society. Currently, our objective is to struggle against and crush those people in authority who are taking the capitalist road, to criticize and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois academic "authorities" and the ideology of the bourgeoisie and all other exploiting classes and to transform education, literature and art, and all other parts of the superstructure that do not correspond to the socialist economic base, so as to facilitate the consolidation and development of the socialist system.

The implications of the Sixteen Points were far-reaching. It elevated what was previously a student movement to a nationwide mass campaign that would galvanize workers, farmers, soldiers and lower-level party functionaries to rise, challenge authority, and re-shape the "superstructure" of society.

On 18 August in Beijing, over a million Red Guards from all over the country gathered in and around Tiananmen Square for a personal audience with the chairman.[15]: 106–07 Mao personally mingled with Red Guards and encouraged their motivation, donning a Red Guard armband himself.[19]: 66 Lin Biao also took centre stage at the August 18 rally, vociferously denouncing all manner of perceived enemies in Chinese society that were impeding the "progress of the revolution."[19]: 66 Subsequently, violence significantly escalated in Beijing and quickly spread to other areas of China.[25][26]

On 22 August, a central directive was issued to stop police intervention in Red Guard activities, and those in the police force who defied this notice were labeled counter-revolutionaries.[15]: 124 Mao's praise for rebellion encouraged actions of the Red Guards.[15]: 515 Central officials lifted restraints on violent behavior in support of the revolution.[15]: 126 Xie Fuzhi, the national police chief, often pardoned Red Guards for their "crimes."[15]: 125 In about two weeks, the violence left some 100 officials of the ruling and middle class dead in Beijing's western district alone. The number injured exceeded that.[15]: 126

The most violent aspects of the campaign included incidents of torture, murder, and public humiliation. Many people who were indicted as counter-revolutionaries died by suicide. During the Red August 1966, in Beijing alone 1,772 people were murdered; many of the victims were teachers who were attacked and even killed by their own students.[27] In Shanghai, there were 704 suicides and 534 deaths related to the Cultural Revolution in September. In Wuhan, there were 62 suicides and 32 murders during the same period.[15]: 124 Peng Dehuai was brought to Beijing to be publicly ridiculed.

Destruction of the Four Olds (August–November)

Between August and November 1966, eight mass rallies were held in which over 12 million people from all over the country, most of whom were Red Guards, participated.[15]: 106 The government bore the expenses of Red Guards traveling around the country exchanging "revolutionary experiences".[15]: 110

At the Red Guard rallies, Lin Biao also called for the destruction of the "Four Olds"; namely, old customs, culture, habits, and ideas.[19]: 66 A revolutionary fever swept the country by storm, with Red Guards acting as its most prominent warriors. Some changes associated with the "Four Olds" campaign were mainly benign, such as assigning new names to city streets, places, and even people; millions of babies were born with "revolutionary"-sounding names during this period.[29]

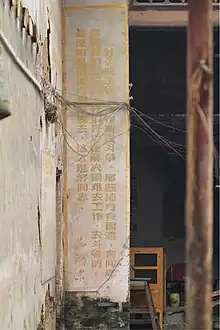

Other aspects of Red Guard activities were more destructive, particularly in the realms of culture and religion. Various historical sites throughout the country were destroyed. The damage was particularly pronounced in the capital, Beijing. Red Guards also laid siege to the Temple of Confucius in Qufu,[15]: 119 and numerous other historically significant tombs and artifacts.[30]

Libraries full of historical and foreign texts were destroyed; books were burned. Temples, churches, mosques, monasteries, and cemeteries were closed down and sometimes converted to other uses, looted, and destroyed.[31] Marxist propaganda depicted Buddhism as superstition, and religion was looked upon as a means of hostile foreign infiltration, as well as an instrument of the ruling class.[32] Clergy were arrested and sent to camps; many Tibetan Buddhists were forced to participate in the destruction of their monasteries at gunpoint.[32]

This statue of the Yongle Emperor was originally carved in stone, and was destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. A metal replica is in its place.

This statue of the Yongle Emperor was originally carved in stone, and was destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. A metal replica is in its place. The remains of the 8th century Buddhist monk Huineng were attacked during the Cultural Revolution.

The remains of the 8th century Buddhist monk Huineng were attacked during the Cultural Revolution. A frieze damaged during the Cultural Revolution, originally from a garden house of a rich imperial official in Suzhou.

A frieze damaged during the Cultural Revolution, originally from a garden house of a rich imperial official in Suzhou.

Central Work Conference (October)

In October 1966, Mao convened a "Central Work Conference", mostly to convince those in the party leadership who had not yet adopted revolutionary ideology. Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping were prosecuted as part of a bourgeois reactionary line and begrudgingly gave self-criticisms.[15]: 137 After the conference, Liu, once a powerful moderate pundit of the ruling class, was placed under house arrest in Beijing, then sent to a detention camp, where he was denied medical treatment and died in 1969. Deng Xiaoping was sent away for a period of re-education three times and was eventually sent to work in an engine factory in Jiangxi. Rebellion by party cadres accelerated after the conference.[34]

End of the year

In Macau, rioting broke out during the 12-3 incident.[35]: 84 The event was prompted by the colonial government's delays in approving a new wing for a Communist Party elementary school in Taipa.[35]: 84 The school board illegally began construction and the colonial government sent police to stop the workers; several people were injured in the resulting conflict.[35]: 84 On December 3, 1966, two days of rioting occurred in which hundreds were injured and six[35]: 84 to eight people were killed, leading also to a total backing down by the Portuguese government.[36] The event set in motion Portugal's de facto abdication of control over Macau, putting Macau on the path to eventual decolonization.[35]: 84–85

1967: Seizure of power

Mass organizations in China roughly coalesced into two hostile factions, the radicals who backed Mao's purge of the Communist party, and the conservatives who backed the moderate party establishment. The "support the left" policy was established in late January 1967.[37] As conceived by Mao, the policy was intended to support the rebels in seizing power; it required the People's Liberation Army (PLA) to support "the broad masses of the revolutionary leftists in their struggle to seize power."[37]

In March 1967, the policy was adapted into the "Three Supports and Two Militaries" initiative, in which PLA troops were sent to schools and work units across the country in an effort to stabilize political tumult and end factional warfare.[38]: 345 The three "Supports" were to "support the left", "support the interior", "support industry". The "two Militaries" referred to "military management" and "military training".[38]: 345 The policy of supporting the left was flawed from inception by its failure to define "leftists" at a time when almost all mass organizations claimed to be "leftist" or "revolutionary".[37] The PLA commanders had developed close working relations with the party establishment, many military units worked to repress radicals.[39]

Spurred by the events in Beijing, "power seizure groups" formed across the country and began expanding into factories and the countryside. In Shanghai, a young factory worker named Wang Hongwen organized a far-reaching revolutionary coalition, one that galvanized and displaced existing Red Guard groups. On January 3, 1967, with support from CRG heavyweights Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan, the group of firebrand activists overthrew the Shanghai municipal government under Chen Pixian in what became known as the "January Storm," and formed in its place the Shanghai People's Commune.[40][21]: 115

Shanghai's was the first provincial level government overthrown.[41] Within days, Mao expressed his approval.[41] Provincial governments and many parts of the state and party bureaucracy were affected, with power seizures taking place in a remarkably different fashion. In the next three weeks, 24 more province-level governments were overthrown.[41] "Revolutionary committees" were subsequently established, in place of local governments and branches of the Communist Party.[42] For example, in Beijing, three separate revolutionary groups declared power seizures on the same day, while in Heilongjiang, the local party secretary Pan Fusheng seized power from the party organization under his own leadership. Some leaders even wrote the CRG asking to be overthrown.[15]: 170–72

In Beijing, Jiang Qing and Zhang Chunqiao made a target out of Vice-Premier Tao Zhu. The power-seizure movement was rearing its head in the military as well. In February, prominent generals Ye Jianying and Chen Yi, as well as Vice-Premier Tan Zhenlin, vocally asserted their opposition to the more extreme aspects of the movement, with some party elders insinuating that the CRG's real motives were to remove the revolutionary old guard. Mao, initially ambivalent, took to the Politburo floor on February 18 to denounce the opposition directly, giving a full-throated endorsement to the radicals' activities. This short-lived resistance was branded the "February Countercurrent"[15]: 195–96 —effectively silencing critics of the movement within the party in the years to come.[19]: 207–09

Although in early 1967 popular insurgencies were still limited outside of the biggest cities, local governments nonetheless began collapsing all across China.[43]: 21 While revolutionaries dismantled ruling government and party organizations all over the country, because power seizures lacked centralized leadership, it was no longer clear who truly believed in Mao's revolutionary vision and who was opportunistically exploiting the chaos for their own gain. The formation of rival revolutionary groups, some manifestations of long-established local feuds, led to violent struggles between factions emerging across the country. Tension grew between mass organizations and the military as well. In response, Lin Biao issued a directive for the army to aid the radicals. At the same time, the army took control of some provinces and locales that were deemed incapable of sorting out their own power transitions.[19]: 219–21

In the central city of Wuhan, like in many other cities, two major revolutionary organizations emerged, one supporting the conservative establishment and the other opposed to it. The groups fought over the control of the city. Chen Zaidao, the Army general in charge of the area, forcibly repressed the anti-establishment demonstrators who were backed by Mao. However, during the commotion, Mao himself flew to Wuhan with a large entourage of central officials in an attempt to secure military loyalty in the area. On July 20, 1967, local agitators in response kidnapped Mao's emissary Wang Li, in what became known as the Wuhan Incident. Subsequently, Gen. Chen Zaidao was sent to Beijing and tried by Jiang Qing and the rest of the Cultural Revolution Group. Chen's resistance was the last major open display of opposition to the movement within the PLA.[15]: 214

The Gang of Four's Zhang Chunqiao, admitted that the most crucial factor in the Cultural Revolution was not the Red Guards or the Cultural Revolution Group or the "rebel worker" organisations, but the side on which the PLA stood. When the PLA local garrison supported Mao's radicals, they were able to take over the local government successfully, but if they were not cooperative, the seizures of power were unsuccessful.[15]: 175 Violent clashes virtually occurred in all cities, according to one historian.

In response to the Wuhan Incident, Mao and Jiang Qing began establishing a "workers' armed self-defense force", a "revolutionary armed force of mass character" to counter what he estimated as rightism in "75% of the PLA officer corps." Chongqing city, a center of arms manufacturing, was the site of ferocious armed clashes between the two factions, with one construction site in the city estimated to involve 10,000 combatants with tanks, mobile artillery, anti-aircraft guns and "virtually every kind of conventional weapon." Ten thousand artillery shells were fired in Chongqing during August 1967.[15]: 214–15

Nationwide, a total of 18.77 million firearms, 14,828 artillery pieces, 2,719,545 grenades ended up in civilian hands. They were used in the course of violent struggles ,which mostly took place from 1967 to 1968. In the cities of Chongqing, Xiamen, and Changchun, tanks, armored vehicles and even warships were deployed in combat.[39]

1968: Purges

In May 1968, Mao launched a massive political purge. Many people were sent to the countryside to work in reeducation camps. Generally, the campaign targeted rebels from the earlier, more populist, phase of the Cultural Revolution.[38]: 239

On 27 July, the Red Guards' power over the PLA was officially ended, and the establishment government sent in units to besiege areas that remained untouched by the Guards. A year later, the Red Guard factions were dismantled entirely; Mao predicted that the chaos might begin running its own agenda and be tempted to turn against revolutionary ideology. Their purpose had been largely fulfilled; Mao and his radical colleagues had largely overturned establishment power.

Liu was expelled from the CCP at the 12th Plenum of the 8th Central Committee in September, and labelled the "headquarters of the bourgeoisie".[44]

Mao meets with Red Guard leaders (July)

As the Red Guard movement had waned over the course of the preceding year, violence by the remaining militant Red Guards increased on some Beijing campuses.[45] Violence was particularly pronounced at Qinghua University, where a few thousand hardliners of two different factions continued to fight.[46] At Mao's initiative, on 27 July 1968, tens of thousands of workers entered the Qinghua campus shouting slogans in opposition to the violence.[46] Red Guards attacked the workers, who continued to remain peaceful.[46] Ultimately, the workers disarmed the students and occupied the campus.[46]

On July 28, 1968, Mao and the Central Group met with the five most important remaining Beijing Red Guard leaders to address the movement's excessive violence and political exhaustion.[45] It was the only time during the Cultural Revolution that Mao met and addressed the student leaders directly. In response to a Red Guard leader's telegram sent prior to the meeting, which claimed that some "Black Hand" had maneuvered the workers against the Red Guards to suppress the Cultural Revolution, Mao told the student leaders, "The Black Hand is nobody else but me! ... I asked [the workers] how to solve the armed fighting in the universities, and told them to go there to have a look."[47]

During the meeting, Mao and the Central Group for the Cultural Revolution stated, "[W]e want cultural struggle, we do not want armed struggle" and "The masses do not want civil war."[48] Mao told the student leaders:[49]

You have been involved in the Cultural Revolution for two years: struggle-criticism-transformation. Now, first, you're not struggling; second, you're not criticizing; and third, you're not transforming. Or rather, you are struggling, but it's an armed struggle. The people are not happy, the workers are not happy, city residents are not happy, most people in schools are not happy, most of the students even in your schools are not happy. Even within the faction that supports you, there are unhappy people. Is this the way to unify the world?

Mao's cult of personality and "mango fever" (August)

In the spring of 1968, a massive campaign that aimed at enhancing Mao's reputation began. A notable example was the "mango fever". On 4 August 1968, Mao was presented with about 40 mangoes by the Pakistani foreign minister Syed Sharifuddin Pirzada, in an apparent diplomatic gesture.[50] Mao had his aide send the box of mangoes to his propaganda team at Tsinghua University on 5 August, the team stationed there to quiet strife among Red Guard factions.[51][50] On 7 August, an article was published in People's Daily, saying:

In the afternoon of the fifth, when the great happy news of Chairman Mao giving mangoes to the Capital Worker and Peasant Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Team reached the Tsinghua University campus, people immediately gathered around the gift given by the Great Leader Chairman Mao. They cried out enthusiastically and sang with wild abandonment. Tears swelled up in their eyes, and they again and again sincerely wished that our most beloved Great Leader lived ten thousand years without bounds ... They all made phone calls to their own work units to spread this happy news; and they also organised all kinds of celebratory activities all night long, and arrived at [the national leadership compound] Zhongnanhai despite the rain to report the good news, and to express their loyalty to the Great Leader Chairman Mao.[51]

Subsequent articles were also written by government officials propagandizing the reception of the mangoes,[52] and another poem in the People's Daily said: "Seeing that golden mango/Was as if seeing the great leader Chairman Mao ... Again and again touching that golden mango/the golden mango was so warm."[53] Few people at this time in China had ever seen a mango before, and a mango was seen as "a fruit of extreme rarity, like Mushrooms of Immortality."[53]

One of the mangoes was sent to the Beijing Textile Factory,[51] whose revolutionary committee organized a rally in the mangoes' honor.[52] Workers read out quotations from Mao and celebrated the gift. Altars were erected to display the fruit prominently. When the mango peel began to rot after a few days, the fruit was peeled and boiled in a pot of water. Workers then filed by and each was given a spoonful of mango water. The revolutionary committee also made a wax replica of the mango and displayed this as a centerpiece in the factory.[51]

There followed several months of "mango fever", as the fruit became a focus of a "boundless loyalty" campaign for Chairman Mao. More replica mangoes were created, and the replicas were sent on tour around Beijing and elsewhere in China. Many revolutionary committees visited the mangoes in Beijing from outlying provinces. Approximately half a million people greeted the replicas when they arrived in Chengdu. Badges and wall posters featuring the mangoes and Mao were produced in the millions.[51]

The fruit was shared among all institutions that had been a part of the propaganda team, and large processions were organized in support of the "precious gift", as the mangoes were known.[54] A dentist in a small town, Dr. Han, saw the mango and said it was nothing special and looked just like a sweet potato. He was put on trial for "malicious slander", found guilty, paraded publicly throughout the town, and then executed with a gunshot to the head.[53][55]

It has been claimed that Mao used the mangoes to express support for the workers who would go to whatever lengths necessary to end the factional fighting among students, and a "prime example of Mao's strategy of symbolic support."[52] Even up until early 1969, participants of Mao Zedong Thought study classes in Beijing would return with mass-produced mango facsimiles, gaining media attention in the provinces.[54]

Down to the Countryside Movement (December)

In December 1968, Mao began the "Down to the Countryside Movement." During this movement, which lasted for the next decade, young bourgeoisie living in cities were ordered to go to the countryside to experience working life. The term "young intellectuals" was used to refer to recently graduated college students. In the late 1970s, these students returned to their home cities. Many students who were previously Red Guard members supported the movement and Mao's vision. This movement was thus in part a means of moving Red Guards from the cities to the countryside, where they would cause less social disruption. It also served to spread revolutionary ideology across China geographically.[56]

1969–71: Rise and fall of Lin Biao

The 9th National Congress held in April 1969 served as a means to "revitalize" the party with fresh thinking—as well as new cadres, after much of the old guard had been destroyed in the struggles of the preceding years.[15]: 285 The party framework of established two decades previously had now broken down almost entirely: rather than through an election by party members, delegates for this Congress were effectively selected by Revolutionary Committees.[15]: 288 Representation of the military increased by a large margin from the previous Congress, reflected in the election of more PLA members to the new Central Committee—with over 28% of delegates being PLA members.[15]: 292 Many officers now elevated to senior positions were loyal to PLA Marshal Lin Biao, which would open a new rift between the military and civilian leadership.[15]: 292

We do not only feel boundless joy because we have as our great leader the greatest Marxist–Leninist of our era, Chairman Mao, but also great joy because we have Vice Chairman Lin as Chairman Mao's universally recognized successor.

— Premier Zhou Enlai at the 9th Party Congress[57]

Reflecting this, Lin Biao was officially elevated to become the Party's preeminent figure outside of Mao, with his name written into the party constitution as his "closest comrade-in-arms" and "universally recognized successor."[15]: 291 At the time, no other Communist parties or governments anywhere in the world had adopted the practice of enshrining a successor to the current leader into their constitutions; this practice was unique to China. Lin delivered the keynote address at the Congress: a document drafted by hardliner leftists Yao Wenyuan and Zhang Chunqiao under Mao's guidance.[15]: 289

The report was heavily critical of Liu Shaoqi and other "counter-revolutionaries" and drew extensively from quotations in the Little Red Book. The Congress solidified the central role of Maoism within the party psyche, re-introducing Maoism as an official guiding ideology of the party in the party constitution. Lastly, the Congress elected a new Politburo with Mao Zedong, Lin Biao, Chen Boda, Zhou Enlai and Kang Sheng as the members of the new Politburo Standing Committee.[15]: 290

Lin, Chen and Kang were all beneficiaries of the Cultural Revolution. Zhou, who was demoted in rank, voiced his unequivocal support for Lin at the Congress.[15]: 290 Mao also restored the function of some formal party institutions, such as the operations of the party's Politburo, which ceased functioning between 1966 and 1968 because the Central Cultural Revolution Group held de facto control of the country.[15]: 296

PLA encroachment

Mao's efforts at re-organizing party and state institutions generated mixed results. The situation in some of the provinces remained volatile, even as the political situation in Beijing stabilized. Factional struggles, many violent, continued at a local level despite the declaration that the 9th National Congress marked a temporary "victory" for the Cultural Revolution.[15]: 316 Furthermore, despite Mao's efforts to put on a show of unity at the Congress, the factional divide between Lin Biao's PLA camp and the Jiang Qing-led radical camp was intensifying. Indeed, a personal dislike of Jiang Qing drew many civilian leaders, including prominent theoretician Chen Boda, closer to Lin Biao.[13]: 115

Between 1966 and 1968, China was isolated internationally, having declared its enmity towards both the Soviet Union and the United States. The friction with the Soviet Union intensified after border clashes on the Ussuri River in March 1969 as the Chinese leadership prepared for all-out war.[15]: 317 In June 1969, the PLA's enforcement of political discipline and suppression of the factions that had emerged during the Cultural Revolution became intertwined with the central Party's efforts to accelerate Third Front work.[16]: 150 Those who did not return to work would be viewed as engaging in 'schismatic activity' which risked undermining preparations to defend China from potential invasion.[16]: 150–51

In October 1969, the Party attempted to focus more on war preparedness and less on suppression of the factions that had emerged during the mass movement phase of the Cultural Revolution.[16]: 151 That month, senior leaders were evacuated from Beijing.[15]: 317 Amidst the tension, Lin Biao issued what appeared to be an executive order to prepare for war to the PLA's eleven military regions on October 18 without going through Mao. This drew the ire of the chairman, who saw it as evidence that his authority was prematurely usurped by his declared successor.[15]: 317

The prospect of war elevated the PLA to greater prominence in domestic politics, increasing the stature of Lin Biao at the expense of Mao.[15]: 321 There is some evidence to suggest that Mao was pushed to seek closer relations with the United States as a means to avoid PLA dominance in domestic affairs that would result from a military confrontation with the Soviet Union.[15]: 321 During his later meeting with Richard Nixon in 1972, Mao hinted that Lin had opposed seeking better relations with the U.S.[15]: 322

Restoration of State Chairman position

After Lin was confirmed as Mao's successor, his supporters focused on the restoration of the position of State Chairman,[note 2] which had been abolished by Mao after the purge of Liu Shaoqi. They hoped that by allowing Lin to ease into a constitutionally sanctioned role, whether Chairman or vice-chairman, Lin's succession would be institutionalized. The consensus within the Politburo was that Mao should assume the office with Lin becoming vice-chairman; but perhaps wary of Lin's ambitions or for other unknown reasons, Mao had voiced his explicit opposition to the recreation of the position and his assuming it.[15]: 327

Factional rivalries intensified at the Second Plenum of the Ninth Congress in Lushan held in late August 1970. Chen Boda, now aligned with the PLA faction loyal to Lin, galvanized support for the restoration of the office of President of China, despite Mao's wishes to the contrary.[15]: 331 Moreover, Chen launched an assault on Zhang Chunqiao, a staunch Maoist who embodied the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, over the evaluation of Mao's legacy.[15]: 328

The attacks on Zhang found favour with many attendees at the Plenum and may have been construed by Mao as an indirect attack on the Cultural Revolution itself. Mao confronted Chen openly, denouncing him as a "false Marxist,"[15]: 332 and removed him from the Politburo Standing Committee. In addition to the purge of Chen, Mao asked Lin's principal generals to write self-criticisms on their political positions as a warning to Lin. Mao also inducted several of his supporters to the Central Military Commission and placed his loyalists in leadership roles of the Beijing Military Region.[15]: 332

Project 571

By 1971, diverging interests between the civilian and military wings of the leadership were apparent. Mao was troubled by the PLA's newfound prominence, and the purge of Chen Boda marked the beginning of a gradual scaling-down of the PLA's political involvement.[15]: 353 According to official sources, sensing the reduction of Lin's power base and his declining health, Lin's supporters plotted to use the military power still at their disposal to oust Mao in a coup.[13]

Lin's son Lin Liguo, along with other high-ranking military conspirators, formed a coup apparatus in Shanghai and dubbed the plan to oust Mao Outline for Project 571—in the original Mandarin, the phrase sounds similar to the term for 'military uprising'. It is disputed whether Lin Biao was directly involved in this process. While official sources maintain that Lin did plan and execute the coup attempt, scholars such as Jin Qiu portray Lin as passive, cajoled by elements among his family and supporters.[13] Qiu contests that Lin Biao was never personally involved in drafting the Outline, with evidence suggesting that Lin Liguo was directly responsible for the draft.[13]

The Outline allegedly consisted mainly of plans for aerial bombardments through use of the Air Force. It initially targeted Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan, but would later involve Mao himself. If the plan succeeded, Lin would arrest his political rivals and assume power. Assassination attempts were alleged to have been made against Mao in Shanghai, from September 8 to 10, 1971. Perceived risks to Mao's safety were allegedly relayed to the chairman. One internal report alleged that Lin had planned to bomb a bridge that Mao was to cross to reach Beijing; Mao reportedly avoided this bridge after receiving intelligence reports.

Lin's flight and plane crash

According to the official narrative, on 13 September Lin Biao, his wife Ye Qun, Lin Liguo, and members of his staff attempted to flee to the Soviet Union ostensibly to seek political asylum. En route, Lin's plane crashed in Mongolia, killing all on board. The plane apparently ran out of fuel en route to the Soviet Union. A Soviet team investigating the incident was not able to determine the cause of the crash but hypothesized that the pilot was flying low to evade radar and misjudged the plane's altitude.

The official account has been put to question by foreign scholars, who have raised doubts over Lin's choice of the Soviet Union as a destination, the plane's route, the identity of the passengers, and whether or not a coup was actually taking place.[13][58]

On 13 September, the Politburo met in an emergency session to discuss Lin Biao. His death was only confirmed in Beijing on 30 September, which led to the cancellation of the National Day celebration events the following day. The Central Committee kept information under wraps, and news of Lin's death was not released to the public until two months following the incident.[13] Many of Lin's supporters sought refuge in Hong Kong. Those who remained on the mainland were purged.[13]

The event caught the party leadership off guard: the concept that Lin could betray Mao de-legitimized a vast body of Cultural Revolution political rhetoric and by extension, Mao's absolute authority, as Lin was already enshrined into the Party Constitution as Mao's "closest comrade-in-arms" and "successor." For several months following the incident, the party information apparatus struggled to find a "correct way" to frame the incident for public consumption, but as the details came to light, the majority of the Chinese public felt disillusioned and realised they had been manipulated for political purposes.[13]

1972–76: The "Gang of Four"

Mao became depressed and reclusive after the Lin Biao incident. With Lin gone, Mao had no ready answers for who would succeed him. Sensing a sudden loss of direction, Mao attempted reaching out to old comrades whom he had denounced in the past. Meanwhile, in September 1972, Mao transferred a 38-year-old cadre from Shanghai, Wang Hongwen, to Beijing and made him vice-chairman of the Party.[15]: 357 Wang, a former factory worker from a peasant background,[15]: 357 was seemingly being groomed for succession.[15]: 364

Jiang Qing's position also strengthened after Lin's flight. She held tremendous influence with the radical camp. With Mao's health on the decline, it was clear that Jiang Qing had political ambitions of her own. She allied herself with Wang Hongwen and propaganda specialists Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan, forming a political clique later pejoratively dubbed as the "Gang of Four".[59]

By 1973, round after round of political struggles had left many lower-level institutions, including local government, factories, and railways, short of competent staff needed to carry out basic functions.[15]: 340 China's economy had fallen into disarray, which necessitated the rehabilitation of purged lower-level officials. The party's core became heavily dominated by Cultural Revolution beneficiaries and leftist radicals, whose focus remained to uphold ideological purity over economic productivity. The economy remained the domain of Zhou Enlai mostly, one of the few moderates 'left standing'. Zhou attempted to restore a viable economy but was resented by the Gang of Four, who identified him as their primary political threat in post-Mao era succession.[60]

In late 1973, to weaken Zhou's political position and to distance themselves from Lin's apparent betrayal, the "Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius" campaign began under Jiang Qing's leadership.[15]: 366 Its stated goals were to purge China of New Confucianist thinking and denounce Lin Biao's actions as traitorous and regressive.[15]: 372

Deng's rehabilitation (1975)

With a fragile economy and Zhou falling ill to cancer, Deng Xiaoping returned to the political scene, taking up the post of Vice-Premier in March 1973, in the first of a series of promotions approved by Mao. After Zhou withdrew from active politics in January 1975, Deng was effectively put in charge of the government, party, and military, earning the additional titles of PLA General Chief of Staff, Vice-chairman of the Communist Party, and vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission in a short time span.[15]: 381

The speed of Deng's rehabilitation took the radical camp, who saw themselves as Mao's 'rightful' political and ideological heirs, by surprise. Mao wanted to use Deng as a counterweight to the military faction in government to suppress any remaining influence of those formerly loyal to Lin Biao. In addition, Mao had also lost confidence in the ability of the Gang of Four to manage the economy and saw Deng as a competent and effective leader. Leaving the country in grinding poverty would do no favours to the positive legacy of the Cultural Revolution, which Mao worked hard to protect. Deng's return set the scene for a protracted factional struggle between the radical Gang of Four and moderates led by Zhou and Deng.

At the time, Jiang Qing and associates held effective control of mass media and the party's propaganda network, while Zhou and Deng held control of most government organs. On some decisions, Mao sought to mitigate the Gang's influence, but on others, he acquiesced to their demands. The Gang of Four's heavy hand in political and media control did not prevent Deng from reinstating his economic policies. Deng emphatically opposed Party factionalism, and his policies aimed to promote unity as the first step to restoring economic productivity.[15]: 381

Much like the post-Great Leap restructuring led by Liu Shaoqi, Deng streamlined the railway system, steel production, and other vital areas of the economy. By late 1975, however, Mao saw that Deng's economic restructuring might negate the legacy of the Cultural Revolution, and launched the Counterattack the Right-Deviationist Reversal-of-Verdicts Trend, a campaign to oppose "rehabilitating the case for the rightists," alluding to Deng as the country's foremost "rightist." Mao directed Deng to write self-criticisms in November 1975, a move lauded by the Gang of Four.[15]: 381

Death of Zhou Enlai

On 8 January 1976, Zhou Enlai died of bladder cancer. On the 15th, Deng Xiaoping delivered Zhou's official eulogy in a funeral attended by all of China's most senior leaders with the notable absence of Mao himself, who had grown increasingly critical of Zhou.[61]: 217–18 [62]: 610 After Zhou's death, Mao selected neither a member of the Gang of Four nor Deng to become Premier, instead choosing the relatively unknown Hua Guofeng.[63]

The Gang of Four grew apprehensive that spontaneous, large-scale popular support for Zhou could turn the political tide against them. They acted through the media to impose a set of restrictions on overt public displays of mourning for Zhou. Years of resentment over the Cultural Revolution, the public persecution of Deng Xiaoping (seen as Zhou's ally), and the prohibition against public mourning led to a rise in popular discontent against Mao and the Gang of Four.[61]: 213

Official attempts to enforce the mourning restrictions included removing public memorials and tearing down posters commemorating Zhou's achievements. On March 25, 1976, Shanghai's Wen Hui Bao published an article calling Zhou "the capitalist roader inside the Party [who] wanted to help the unrepentant capitalist roader [Deng] regain his power." These propaganda efforts at smearing Zhou's image, however, only strengthened public attachment to Zhou's memory.[61]: 214

Tiananmen incident

On 4 April 1976, on the eve of China's annual Qingming Festival, a traditional day of mourning, thousands of people gathered around the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square to commemorate Zhou Enlai. The people of Beijing honored Zhou by laying wreaths, banners, poems, placards, and flowers at the foot of the Monument.[62]: 612 The most apparent purpose of this memorial was to eulogize Zhou, but the Gang of Four were also attacked for their actions against the Premier. A small number of slogans left at Tiananmen even attacked Mao himself, and his Cultural Revolution.[61]: 218

Up to two million people may have visited Tiananmen Square on 4 April.[61]: 218 All levels of society, from the most impoverished peasants to high-ranking PLA officers and the children of high-ranking cadres, were represented in the activities. Those who participated were motivated by a mixture of anger over the treatment of Zhou, revolt against the Cultural Revolution and apprehension for China's future. The event did not appear to have coordinated leadership but rather seemed to be a reflection of public sentiment.[61]: 219–20

The Central Committee, under the leadership of Jiang Qing, labelled the event 'counter-revolutionary' and cleared the square of memorial items shortly after midnight on April 6. Attempts to suppress the mourners led to a violent riot. Police cars were set on fire, and a crowd of over 100,000 people forced its way into several government buildings surrounding the square.[62]: 612 Many of those arrested were later sentenced to prison. Similar incidents occurred in other major cities. Jiang Qing and her allies pinned Deng Xiaoping as the incident's 'mastermind', and issued reports on official media to that effect. Deng was formally stripped of all positions "inside and outside the Party" on 7 April. This marked Deng's second purge in ten years.[62]: 612

Death of Mao and the Gang of Four's downfall

On 9 September 1976, Mao Zedong died. To Mao's supporters, his death symbolized the loss of the revolutionary foundation of Communist China. When his death was announced on the afternoon of 9 September, in a press release entitled "A Notice from the Central Committee, the NPC, State Council, and the CMC to the whole Party, the whole Army and to the people of all nationalities throughout the country,"[64] the nation descended into grief and mourning, with people weeping in the streets and public institutions closing for over a week. Hua Guofeng chaired the Funeral Committee and delivered the memorial speech.[65][66]

Shortly before dying, Mao had allegedly written the message "With you in charge, I'm at ease," to Hua. Hua used this message to substantiate his position as successor. Hua had been widely considered to be lacking in political skill and ambitions, and seemingly posed no serious threat to the Gang of Four in the race for succession. However, the Gang's radical ideas also clashed with influential elders and a large segment of party reformers. With army backing and the support of Marshal Ye Jianying, on October 6, the Central Security Bureau's Special Unit 8341 had all members of the Gang of Four arrested in a bloodless coup.[67]

After Mao's death, people characterized as 'beating-smashing-looting elements', who were seen as having disturbed the social order during the earlier phases of the Cultural Revolution, were purged or punished.[38]: 359 "Beating-smashing-looting elements" had typically been aligned with rebel factions.[38]: 359

Aftermath

Transitional period

Although Hua Guofeng publicly denounced the Gang of Four in 1976, he continued to invoke Mao's name to justify Mao-era policies. Hua spearheaded what became known as the Two Whatevers,[68] namely, "Whatever policy originated from Chairman Mao, we must continue to support," and "Whatever directions were given to us from Chairman Mao, we must continue to follow." Like Deng, Hua wanted to reverse the damage of the Cultural Revolution; but unlike Deng, who wanted to propose new economic models for China, Hua intended to move the Chinese economic and political system towards Soviet-style planning of the early 1950s.[69][70]

It became increasingly clear to Hua that, without Deng Xiaoping, it was difficult to continue daily affairs of state. On October 10, Deng Xiaoping personally wrote a letter to Hua asking to be transferred back to state and party affairs; party elders also called for Deng's return. With increasing pressure from all sides, Premier Hua named Deng Vice-Premier in July 1977, and later promoted him to various other positions, effectively catapulting Deng to China's second-most powerful figure. In August, the 11th National Congress was held in Beijing, officially naming (in ranking order) Hua Guofeng, Ye Jianying, Deng Xiaoping, Li Xiannian and Wang Dongxing as new members of the Politburo Standing Committee.[71]

Repudiation and reform under Deng

Deng Xiaoping first proposed what he called Boluan Fanzheng in September 1977 in order to correct the mistakes of the Cultural Revolution. In May 1978, Deng seized the opportunity to elevate his protégé Hu Yaobang to power. Hu published an article in the Guangming Daily, making clever use of Mao's quotations while lauding Deng's ideas. Following this article, Hua began to shift his tone in support of Deng. On July 1, Deng publicized Mao's self-criticism report of 1962 regarding the failure of the Great Leap Forward. His power base expanding, in September Deng began openly attacking Hua Guofeng's "Two Whatevers".[68]

On 18 December 1978, the pivotal Third Plenum of the 11th Central Committee was held. At the congress, Deng called for "a liberation of thoughts" and urged the party to "seek truth from facts" and abandon ideological dogma. The Plenum officially marked the beginning of the economic reform era, with Deng becoming the second paramount leader of China. Hua Guofeng engaged in self-criticism and called his "Two Whatevers" a mistake. Wang Dongxing, a trusted ally of Mao, was also criticized. At the Plenum, the Party reversed its verdict on the Tiananmen Incident. Disgraced former Chinese president Liu Shaoqi was allowed a belated state funeral.[72] Peng Dehuai, one of China's ten marshals and the first Minister of National Defense, was persecuted to death during the Cultural Revolution; he was politically rehabilitated in 1978.

At the Fifth Plenum held in 1980, Peng Zhen, He Long and other leaders who had been purged during the Cultural Revolution were politically rehabilitated. Hu Yaobang became head of the party secretariat as its secretary-general. In September, Hua Guofeng resigned and Zhao Ziyang, another Deng ally, was named premier. Deng remained the Chairman of the Central Military Commission, but formal power was transferred to a new generation of pragmatic reformers, who reversed Cultural Revolution policies to a large extent during the Boluan Fanzheng period. Within a few years from 1978, Deng Xiaoping and Hu Yaobang helped rehabilitate over 3 million "unjust, false, erroneous" cases in Cultural Revolution.[73] In particular, the trial of the Gang of Four took place in Beijing from 1980 to 1981, and the court stated that 729,511 people had been persecuted by the Gang, of whom 34,800 were said to have died.[74]

In 1981, the Chinese Communist Party passed a resolution and declared that the Cultural Revolution was "responsible for the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the Party, the country, and the people since the founding of the People's Republic."[7][8][9]

Atrocities

Death toll

Death toll estimates vary greatly across different sources, ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions, or even tens of millions.[78][79][80][81][82][83] In addition to various regimes of secrecy and obfuscation concerning the Revolution, both top-down as perpetuated by authorities, as well as laterally among the Chinese public in the decades since, the massive variance in estimates are due in large part to the totalistic nature of the Revolution itself: it is a significant challenge for historians to discern whether and in what ways discrete events that took place during the Cultural Revolution should be ascribed to it.[84] For example, the 1975 Banqiao Dam failure, considered by some to be the greatest technological catastrophe of the 20th century, resulted in an death toll between 26,600 and 240,000 people. The scope of the collapse, which occurred near the end of the Cultural Revolution, was covered up by authorities until at least 1989.[85][86]

Most deaths ascribed to the Cultural Revolution occurred after the mass movements ended,[87] when there were organized campaigns to consolidate order in workplaces and communities.[88]: 172 As Walder summarizes, "The cure for factional warfare was far worse than the disease."[87]

Literature reviews of the overall death toll due to the Cultural Revolution usually include the following:[79][89][90]

| Time | Source | Deaths (in millions) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Andrew G. Walder | 1.1–1.6[91] | Examines the period between 1966 and 1971.[91] Walder reviewed the reported deaths in 2,213 annals from every county and interpreted the annals' vague language in the most conservative manner. For instance, "some died" and "a couple died" were interpreted as zero death, while "death in the scale of tens/hundreds/thousands" were interpreted as "ten/a hundred/a thousand died". While critics praised this approach as "much more empirical than other approaches",[89] the reported deaths certainly underestimate the actual deaths, especially because some annals actively cover up deaths.[79][90][92] It should also be noted that the editors of the annals were supervised by the CCP Propaganda Department.[79][92] In 2003, Walder and Yang Su coauthored a paper along this approach, but with fewer county annals available at the time.[89][93] |

| 1999 | Ding Shu | 2[94] | Ding's figures include 100,000 killed in the Red Terror during 1966, with 200,000 forced to commit suicide, plus 300,000–500,000 killed in violent struggles, 500,000 during the Cleansing the Class Ranks, 200,000 in the One Strike-Three Anti Campaign and the Anti-May Sixteenth Elements Campaign.[94][79][89][90] |

| 1996 | CCP History Research Center | 1.728[95] | The 1.728 million were counted as "unnatural deaths", among which 9.4% (162,000) were CCP party members and 252,000 were intellectuals. The figures were extracted from 《建国以来历次政治运动事实》; 'Facts on the Successive Political Movements since the Founding of the PRC', a book by the party's History Research Center, which states that "according to CCP internal investigations in 1978 and 1984 ... 21.44 million were investigated, 125 million got implicated in these investigations; [...] 4.2 million were detained (by Red Guards and other non-police), 1.3 million were arrested by police, 1.728 million of unnatural deaths; [...] 135,000 were executed for crimes of counter-revolution; [...] during violent struggles 237,000 were killed and 7.03 million became disabled".[95][96] While these internal investigations were never mentioned or published in any other official documents, the scholarly consensus found these figures very reasonable.[90] Chen Yung-fa endorsed the figures, yet he noted that peasants suffered far more in the Great Leap Forward than in the Cultural Revolution.[97] |

| 1991 | Rudolph J. Rummel | 7.731[98] | Rummel included his estimate of Laogai camp deaths in this figure.[89] He estimated that 5% of the 10 million people in the Laogai camps died each year of the 12-year period, and that this amounts to roughly 6 million. He estimated that another 1.613 million were killed outright, a middle-ground figure he picked between 285,000 and 10,385,000, a range he deemed plausible.[98] |

| 1982 | Ye Jianying | 3.42 | Several sources have recorded a statement made by Marshal Ye Jianying, of "683,000 deaths in the cities, 2.5 million deaths in the countryside, among which 1.2 million belong to the 'rich peasants' class, much more than the deaths of 0.2 million rich peasants in the Communist land redistribution campaign."[90][95][99] In a 2012 interview with Hong Kong's Open Magazine, an unnamed bureaucrat in Beijing claimed that Ye made the statement in a 1982 CCP meeting, while he was the party's Vice Chairman.[90][99] Several sources have also claimed that Marshal Ye estimated the death toll to be 20 million during a CCP working conference in December 1978.[79][80][81][82][90] |

| 1979 | Agence France Presse | 0.4[100] | This figure was obtained by an AFP correspondent in Beijing, citing an unnamed but "usually reliable" source.[100] In 1986, Maurice Meisner referred to this number as a "widely accepted nationwide figure", but also said "The toll may well have been higher. It is unlikely that it was less."[101] Jonathan Leightner asserted that the number is "perhaps one of the best estimates".[102] |

Massacres

During the Cultural Revolution, massacres took place across China, including in Guangxi, Inner Mongolia, Guangdong, Yunnan, Hunan, and Ruijin, as well as Red August in Beijing.[103]

These massacres were mainly led and organized by local revolutionary committees, Communist Party branches, militia, and even the military.[103][104][105] Most of the victims in the massacres were members of the Five Black Categories as well as their children, or members of "rebel groups". Chinese scholars have estimated that at least 300,000 people died in these massacres.[104][106] Collective killings in Guangxi and Guangdong were among the most serious. In Guangxi, the official annals of at least 43 counties have records of massacres, with 15 of them reporting a death toll of over 1,000, while in Guangdong at least 28 county annals record massacres, with 6 of them reporting a death toll of over 1,000.[105]

In 1975, the PLA led a massacre in Yunnan around the town of Shadian, targeting Hui people, resulting in the deaths of more than 1,600 civilians, including 300 children, and the destruction of 4,400 homes.[103][107][108]

In Dao County, Hunan, a total of 7,696 people were killed from 13 August to 17 October 1967, in addition to 1,397 forced to commit suicide, and 2,146 being permanently disabled.[109][110] During Beijing's Red August in 1966, official sources in 1980 have revealed that at least 1,772 people were killed by Red Guards, including teachers and principals of many schools; additionally, 33,695 homes were ransacked and 85,196 families were forced to leave the city.[27][111][112] The Daxing Massacre caused the deaths of 325 people from August 27 to September 1, 1966; those killed ranged from 80 years old to a 38-day old baby, with 22 families being completely wiped out.[103][111][113]

Cannibalism in Guangxi