Shanghai People's Commune

The Shanghai People's Commune (Chinese: 上海人民公社; pinyin: Shànghǎi Rénmín Gōngshè) was established in January 1967 during the January Storm (Chinese: 一月风暴), also known as the January Revolution (Chinese: 一月革命),[1] of China's Cultural Revolution by the Shanghai Workers Revolutionary Rebel General Headquarters. The Commune was modelled on the Paris Commune. It lasted less than a month before it was dissolved by the government.

| Shanghai People's Commune 上海人民公社 | |

|---|---|

| People's commune of | |

| 1967 | |

.svg.png.webp) Location of Shanghai in China | |

| History | |

| Government | Revolutionary committee |

| • Type | Commune |

| Chairman | |

• 1967 | Zhang Chunqiao |

| Historical era | Cultural Revolution |

• Established | 5 January 1967 |

• Proclaimed | 5 February 1967 |

• Disestablished | 24 February 1967 |

Background

As the mass mobilization phase Cultural Revolution gained momentum in 1966, it became evident that Chairman Mao Zedong and his Maoist followers in Beijing had underestimated the ability of local party organizations to resist the attacks from Red Guards. By the end of 1966 many regional party groupings had survived by paying lip service to Maoist teachings while countering the attacks of local Maoists.[2]

To break the stalemate which had begun to form, Maoist leaders called for the "seizure of power by proletarian revolutionaries", a concept originally mentioned in the Sixteen Articles (a statement of the aims of the Cultural Revolution approved at the 11th Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party in August 1966).

Shanghai was the most industrialized city in China and accounted for almost half of the country's industrial production.[3] Shanghai's experience of the Cultural Revolution had begun in the summer of 1966 with the formation of Red Guard groups proclaiming their loyalty to Chairman Mao. The movement quickly became heavily factionalized (as was the norm), but also rapidly developed very radical tendencies, with attacks on the authority of the city's mayor and physical attacks on government buildings.[4] By the autumn of the same year, the spirit of rebellion had spread from the city's schools to the factories, and there soon followed the creation of many different worker-based groups. In November, several of these groups proceeded to form an alliance (the Shanghai Workers Revolutionary Rebel General Headquarters) led by Wang Hongwen.

The formation of the Shanghai Workers Revolutionary Rebel General Headquarters perplexed the party's leadership and even Maoist leaders of the Central Group of the Cultural Revolution initially did not take a clear position.[5] Shanghai officials Chen Pixian (head of the Shanghai Party Committee) and Cao Diqiu (Mayor of Shanghai) opposed the group and declared it illegal.[5] The Shanghai bureaucracy viewed the group as counterrevolutionary.[5]

By this point, the Cultural Revolution in Shanghai was proceeding at a rapid pace. On 8 November, the Workers General Headquarters presented a list of demands to the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee demanding the replacement of the old "bureaucracy" with new organs that had widespread support. These demands were refused. The group arranged for mass delegations to travel to Beijing with the intent of meeting the Central Group of the Cultural Revolution to make their case that the Workers General Headquarters was a revolutionary political organization.[5] The authorities blocked the train at Anting, a station at the edge of Shanghai, and kept it waiting for two days.[5] The worker delegation refused to leave the train and the authorities would not yield.[5]

The response from the Maoist leaders in Beijing was one of caution. Their first response was to send a telegram drafted by Chen Boda.[5] The telegram did not address any of the workers' requests, but instead urged all involved to come down, return to work, and to "take firm hold of the revolution and promote production[.]"[6] Wang Hongwen insisted that the telegram must be false and that the workers must go to Beijing to speak directly with party leaders.[7] Academic Alessandro Russo describes the impasse as unprecedented because "[i]n a socialist state founded on the dictatorship of the proletariat, here were workers declaring themselves revolutionary communists while affirming their intransigence on a fully political matter, namely their capacity to organize themselves autonomously. Their position was an open challenge to all forms of established political organization, including that of the Maoist group."[7] The impasse ultimately led to the demise of Chen Boda's career.[3]

On November 11, 1966, the Central Group of the Cultural Revolution sent Zhang Chunqiao to address the situation.[7] The Central Group did not give Zhang a specific mandate regarding how he should do so.[7] On his arrival in Shanghai, Zhang performed a thorough investigation, meeting with both participants in, and observers of, the events.[7] He listened to the workers' requests and shortly thereafter, assumed responsibility for (and took the risk of) accepting their demands.[7] After intense negotiations, Zhang reached an agreement with the Workers General Headquarters: their declaration that they were an independent revolutionary organization was accepted as correct, but they would address their grievances and concerns in an upcoming series of meetings in Shanghai, rather than with the Beijing leadership.[8]

The Central Group of the Cultural Revolution agreed with Zhang's handling of the situation and Mao specifically praised him.[8]

Tensions remained with the party leadership in Shanghai because the agreement negotiated by Zheng contradicted their position.[8] Because they had not signed the agreement, Shanghai party officials did not recognize themselves as legally bound to it.[8] Chen Pixian and Cao Diqiu maintained that Zheng had "capitulated" to the demands of thugs and had thereby renounced the organizational principles of the party itself.[8] Local party authorities responded by setting up a "loyalist" workers organization, backed by official trade unions and the party organization within factories.[8] The group was largely composed of technicians and other skilled workers.[3] To create an association with political orthodoxy, the loyalist organization was named the Scarlet Guards (chi weidui), i.e., a shade "redder than red."[8] The Scarlet Guards had one element to their political program: repudiate the existence of the Workers General Headquarters as enemies of the working class in favor of the legitimacy of the local authorities.[8]

Other workers groups also arose in Shanghai in addition to the Workers General Headquarters and the Scarlet Guards.[3] On the other end of the spectrum from the conservative Scarlet Guards were the most radical of these groups, the Workers' Second Regiment.[3] By the end of 1966, most workers in Shanghai were in one of the several competing groups.[3]

In December, the Scarlet Guards provoked a violent confrontation with the Workers General Headquarters.[3] The Workers General Headquarters learned of how the Shanghai Party Committee had bought off workers to control the Scarlet Guards and rallied other workers to their side, defeating the Scarlet Guards.[3]

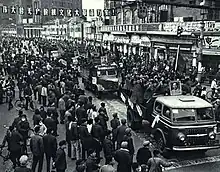

Establishment

On 5 January 1967, a dozen groups allied with the Worker's Headquarters grouping published a "Message to all the People of Shanghai" in the city's main newspaper, calling for unity in the workers' movement. The message condemned the Scarlet Guards and the Party and called on all workers to resume production.[3] In a mass meeting led by the Workers General Headquarters on 6 January, Shanghai Party Committee leaders and functionaries were humiliated and dismissed from their posts.[3] Rebel party cadres also played a major role in the collapse of the Shanghai Party Committee.[9] Three days after the mass meeting, Mao described the events in Shanghai as a "great revolution" and stated that the "upsurge of revolutionary power in Shanghai has brought hope to the whole country."[10]

Now leaders of the Central Group for the Cultural Revolution, Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan came to Shanghai.[11] The pair proceeded to strike a deal with Wang Hongwen to guarantee the support of the Worker's Headquarters[12] and attempted to restore the city to order.[11]

Zhang, Yao, and Wen announced the Shanghai Commune, a model based on the Paris Commune.[11] On 5 February 1967, the Shanghai Commune was formally proclaimed with Zhang Chunqiao as the head of the new organisation, but the movement was to be short-lived and marred with difficulty.

Radical groups like the Workers' Second Regiment criticized this new alliance as one imposed from Beijing rather than self-determined by the workers.[11] Violence again broke out in between workers groups in the city and lasted through February.[11]

Manifesto

The Shanghai People's Commune manifesto began, "We proletarian revolutionaries of Shanghai proclaim to the whole country and the whole world that in the great January Revolutionary Storm the old Municipal Committee of Shanghai has collapsed, and the Shanghai People's Commune was born."[13] Its theme overwhelmingly focused on the critical Cultural Revolution concept, the seizure of power.[13] Among its 63 references to seizure of power (in the course of only a few pages), the Manifesto states, "The central task of all our tasks is to take power. We must seize power, seize it completely, seize it one hundred percent."[14]

It repeated some statements by Mao, which included a frequent theme of revolutionary culture articulated by Mao in a 1933 speech: "All revolutionary struggles in the world are made to take political power and strengthen it."[13] The Manifesto also cited two lines from Mao's 1963 poem Response to Guo Muruo: "The Four Seas are rising, clouds and water raging / the Five Continents are rocking, wind and thunder roaring."[13]

Although the Manifesto described the commune as only "a first step," it did not address future goals other than general statements on issues like workers making revolution, stimulating production, self-reforming, and preventing revisionists authorities from seizing power back.[13]

Aftermath

Meanwhile, in Beijing, the concept of 'revolutionary committees' (triple alliances between the PLA, cadres, and workers) had attracted Mao as the best organ of local government to replace the old apparatus with. As a result, in an audience with Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan in mid-February, Mao suggested the transformation of the Shanghai Commune into a revolutionary committee.[15] In this meeting, Mao commented on what he described as the "name" problem, stating that the "name" should not be confused with the "real" and the name of the Commune should not be exaggerated because "names come and go."[16] Mao said that if taken only as a synonym for seizing power, the name "Commune" obscured the more pressing strategic task of re-examining the history of revolutionary culture.[17] While Mao endorsed the overall approach, he stated that the movement should be deepened with study.[11] On February 24, in a televised speech to the people of Shanghai, Zhang announced the now non-existence of the Shanghai Commune, and in the subsequent weeks the 'Revolutionary Committee of the Municipality of Shanghai' was established in the city.

In the months following the January Storm, the nationwide political climate changed rapidly.[18] Most independent organizations weakened and collapsed from the constant factional conflict.[18] In almost every city and danwei, the multiplicity of organizations was replaced by pairs of rival organizations, for example the "Sky" and "Earth" factions among Beijing students.[18] As time went on, the head-on clashes between these pairs of rival organizations generally became increasingly formalist and lacking in political content.[18]

Between 1968 and 1976, one million skilled workers from Shanghai were sent to rural underdeveloped inner China, officially to share their "revolutionary experiences" and to help develop the country.[19][20] Some radical leaders who had opposed the Red Guards that dethroned the Shanghai Municipal Committee in 1967 were publicly executed in April 1968.[20]

References

- "January Storm". maozhang.net.

- Meisner 1986, p. 342.

- Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the twentieth-century world : a concise history. Durham [NC]: Duke University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4. OCLC 503828045.

- Meisner 1986, p. 343.

- Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- Walder, Andrew G. (2019). Agents of disorder : inside China's Cultural Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-674-24363-7. OCLC 1120781893.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the twentieth-century world : a concise history. Durham [NC]: Duke University Press. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4. OCLC 503828045.

- Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the twentieth-century world : a concise history. Durham [NC]: Duke University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4. OCLC 503828045.

- Meisner 1986, p. 347.

- Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- MacFarquhar & Schoenhals 2006, p. 168.

- Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- Hongsheng & Hazan 2014, p. 230.

- Courtois 1999, p. 628.

Further reading

| Library resources about Shanghai People's Commune |

- Badiou, Alain (2018). Pétrograd, Shanghai. Les deux révolutions du XXe siècle (in French). éditions La Fabrique.

- Bergère, Marie-Claire (1989). La République populaire de Chine de 1949 à nos jours (in French). Paris: Armand Colin.

- Guokai, Liu (2006). "La Revolution Culturelle" (PDF) (in French). Le Courrier International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2008.

- Hongsheng, Jiang (2010). The Paris Commune in Shanghai: the Masses, the State, and Dynamics of "Continuous Revolution" (PDF) (PhD). Duke University.

- Hongsheng, Jiang; Hazan, Éric (2014). La Commune de Shanghai et la Commune de Paris. Paris: La Fabrique. p. 338. ISBN 978-2-35872-063-2. OCLC 893662332.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick; Schoenhals, M. (2006). Mao's Last Revolution. Belknap Harvard.

- Meisner, Maurice (1986). Mao's China and After: A History of the People's Republic since 1949. Free Press.