Kowaliga, Alabama

Kowaliga, also known as Kowaliga Industrial Community[1] and Benson,[2] was a former unincorporated village and historically African-American community active from roughly 1890 until 1926, and located in Elmore County and later Tallapoosa County in Alabama, United States.[3]

Kowaliga

Benson Kowaliga Industrial Community | |

|---|---|

Rural village | |

Lake Martin aerial view, including Kowaliga Bridge | |

Kowaliga | |

| Coordinates: 32.742718°N 85.962721°W | |

| Establishment | c. 1890 |

| Closure | c. 1926 |

| Founded by | John Jackson Benson |

| Government | |

| • Community leader | William E. Benson |

| Address | Elmore County, and Tallapoosa County, Alabama, U.S. |

The area started as a Muscogee tribal land of the same name and in the same location. In the late 19th-century and early 20th-century the African American community was founded by John Jackson Benson with support from his son William E. Benson. Benson had been enslaved and upon release he worked to purchase his former owners plantation land. The community had been the home of industrial farming and business; the Kowaliga School, a private school for learning industrial and domestic skills; the Dixie Industrial Company, a business enterprise to provide work and experience for students and the community; and the short-lived Dixie Line, the first Black-owned railroad built in 1914.[1][4] Not much is known about the detailed history but many photographs exist, and it has been a renewed focus of researchers starting in the early 2000s.

Part of the former community is now submerged under the Kowaliga Bridge spanning Lake Martin,[5] which occurred after the completion of the Martin Dam in 1926. The name "Kowaliga" has been used to describe many modern-day places in the area of Lake Martin, particularly in or near the former community.

Pre-history

The name of the community was derived from a Native American name.[6][7] The community has roots that date back to the Muscogee tribe.[8] There is a local legend about a lone Muscogee man named Kowaliga that lived on the shore of Kowaliga creek, after being rejected for love by a women.[7]

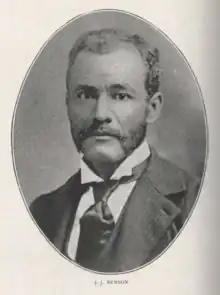

The historically African American community of Kowaliga was established by John Jackson Benson (September 1850–November 9, 1925), a formerly enslaved person, who was likely biracial.[5][8] He was owned by James Benson, a Virginian who owned the Benson Plantation near Kowaliga Creek in Alabama.[5][9] It is theorized by some researchers that John Jackson Benson's mother was a slave and James Benson may have been his illegitimate father.[8] When his enslaver James Benson died, and the Benson estate divided among his relatives. John Jackson Benson was sent to Talladega to continue to work as a slave for an heir.[5]

Many of the Southern plantations were seized during the war after the passage of the Confiscation Act of 1861.[5] At the end of the American Civil War in 1865, John Jackson Benson was freed, given a mule, and went to Florida to find his sister and bring her back to Alabama.[5] Benson had been separated from his sister in childhood and they were eventually reunited in Florida. He had the goal of purchasing the Benson Plantation but he needed money, so John Jackson Benson moved to Shelby County to work in the coal mines, which could be a fast way to make money at the time.[5]

History

.png.webp)

The purpose of the formation of the community was the creation of economic self-sufficiency for local African Americans,[10] which was notable particularly in the late-19th-century and early 20th-century.

John Jackson Benson had earned US $100 from working in the coal mines and purchased a portion of the land from the former plantation, and worked that land. By 1890, he owned 160 acres of land, and by 1898 had acquired 3,000 acres of land.[5] On this land he built a large farmhouse, a sawmill, a cotton gin, a gristmill, and a brickyard.[5][11] Around forty Black and White families lived together on Benson's land.[5] They grew cotton, sugar cane, and different types of wood for lumber (pine, oak, and hickory).[5] John Jackson Benson used his wealth offering loans to both Black and White people.[5]

Kowaliga School

John Jackson Benson gave his son William E. Benson (1873–1915) 10 acres in order to build a private school for the Black community.[5][12][13] The goal in the school creation was for rural students to eventually find industrial work with their new experiences, or alternatively create an educational foundation for these students in order to continue their education at other institutions afterwards.[13] The Kowaliga Academy and Industrial Institute (or Kowaliga Industrial School) was established in roughly 1895, the first building cornerstone was laid on August 1896,[13] and it was incorporated in 1899.[4][5][14]

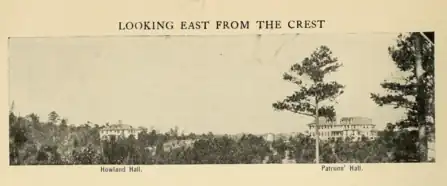

The first school building was named Patron's Hall, and it was funded by 70 Black farm workers.[13] The first board of trustees for the school during incorporation were John Jackson Benson, William E. Benson, Solomon Robinson, Jackson Robinson, Emily Howland, Mrs. J. L. Kaine, and Clinton J. Calloway.[13] Oswald Garrison Villard and Booker T. Washington served later on the board of trustees and advised Benson on developing the community.[4][8] William E. Benson had attended Howard University, he was well connected to other middle class African Americans, and he often would photograph the Kowaliga community and traveled to the north with his photographs in order to fundraise for the school and tuition scholarships.[8][4][13]

William Gray Purcell, an architecture student at Cornell University, was hired around 1899 by William E. Benson to draft architectural designs for Kowaliga, with the goal of expanding their housing and campus.[15] None of the Purcell designs for Kowaliga were built, after there was a lynching in the village.

The Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute campus consisted of wooden structures and one of the buildings burned down in 1909,[1] but William E. Benson fundraised and rebuilt it.[8] Andrew Carnegie donated US $20,000 (roughly worth half a million dollars in 2021) for the rebuild,[8] administered through regular payments by the Title Guarantee and Trust Company of New York City.[16] Emily Howland also supported the rebuilding and Howland Hall was named for her. Isabel Barrows wrote about a visit to the school for the laying of the cornerstone.[17]

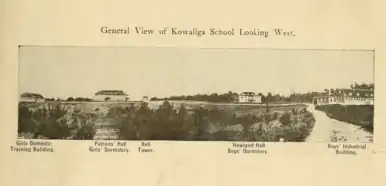

After 1909, Booker T. Washington stepped down from the board of trustees of the school,[8] in what may have been a falling out with Benson. The school principal was W. Rutherford Banks from 1912 until 1915.[18] In 1912, Rev. J.A. Myers served as "president" of the school.[3][19] Other school buildings by 1912 included an industrial training building for boys, a domestic training building for girls, and two dormitories (one for boys and one for girls).[13] After William E. Benson's death in 1915, the Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute continued to function for another 10 years.[13]

The school operated for over 30 years and educated hundreds of children, but eventually closed around 1925.[4] The school building later became the site of the Hotel Camp Dixie which operated until the 1950s, but burned down in a fire in the 1960s.[8] A Rosenwald School was created to replace the Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute, the building is abandon but still standing and located across from Russell Crossroads in Tallapoosa County.[2]

- Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute, images from c. 1912 to 1913

View west of buildings at Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute

View west of buildings at Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute View east of buildings at Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute

View east of buildings at Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute Partial group of teachers

Partial group of teachers

Dixie Industrial Company

In 1900, William E. Benson serving as the founding President added to the Dixie Industrial Company, an industry centered company designed to put his former students to work locally. The company initially included a modern sawmill, a large turpentine distillery, and a cotton ginnery. The Dixie Industrial Company farming was spread over 10,000 acres. Many of the same northern donors to the Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute also invested in funding the Dixie Industrial Company.[8]

The Dixie Industrial Company was also a builder of the first Black-owned railroad known as the Dixie Line (1914),[8] only 16 miles long and connected Kowaliga to the Alabama railroad network. The railroad terminus was in Alexander City.[8] After the creation of the railroad line, the company was able to send lumber to the Atlantic port and export to Europe with a focus on Germany. However due to the onset of World War I in 1914, the Atlantic port closed.

The Dixie Industrial Company lost financial control as a result of the port closure due to war. In June 1915, William E. Benson stepped down from the company after pressure from the largest stockholder Clarence H. Kelsey of the Title Guarantee and Trust Company, Benson was succeeded by New York City lawyer C. Amos Brooks.[20] Benson vowed to take the title company to court over the power issue.[2][20] In 1916, mere months after William E. Benson's death in October 1915, the Dixie Industrial Company sold timber rights to J. M. Steverson and Benjamin Russell of the Pine Lumber Company.[2] In 1920,[6] the Supreme Court of Alabama heard the case Dixie Industrial Co. vs. Benson, in a lawsuit with John Jackson Benson filing against the railroad title company, over a lien on the land.[21] During the lawsuit deceased William E. Benson was represented by his father.[2][21]

Community closure

The community closed due to many factors, but specifically the impacts from the creation of Martin Dam built by the Alabama Power Company that submerged the town of Kowaliga (and Kowaliga Creek) to form Lake Martin in 1926. John Jackson Benson had died a few months before the completion of the dam.[14] Other factors that effected the closure included the end of World War I which affected the financial health of the Dixie Industrial Company, and a drop in cotton prices which impacted the industrial farming community.[14] In those days many people moved from the area of Lake Martin, fearing diseases like malaria.

As of 2021, the land that was once part of this community is owned by the Russell Lands, a housing development company.[8] Not much still exists of the structures, only some quartz rock and a former concrete foundation, located near the rebuilt bell tower.[8]

Legacy

The Kowaliga school educated hundreds of Black children in its many years of operations.[4] The formation of the Dixie Industrial Company as an extension of the school had proved less successful by maintaining operations for less than 16 years but it provided many "firsts" for the Black community, including a new model for industrial and educational work in the rural south.

The Hank Williams song, "Kaw-Liga" (1953) about a wooden Indian statue that fell in love, shares the name of the former community on Lake Martin.[7][22][23][24] In August 1952, Williams vacationed at Lake Martin while he wrote songs including "Kaw-Linga", this song was originally spelled as "Kowaliga" but it was changed by Fred Rose in order to focus on the song's storyline.[22][23][25] In 1953, "Kowaliga Day" was proclaimed by Alexander City Mayor Joe Robinson, because of the successful song.[25]

While there are early publications about this place and photographs, much of the history was lost. A renewed interest in research developed since the 2000s.[8] In 2005, Alabama Heritage Magazine published a story on the community.[8] Amateur historians Erica Buddington and Thomas C. Coley, Jr. have focused their research on Kowaliga / Benson.[4]

See also

- Black mecca, colloquialism for a location featuring high or potential Black economic prosperity

- Creek War of 1813 to 1814, said to have affected the area

- List of plantations in Alabama

- List of flooded towns in the United States

References

- The American Educational Review. Vol. 30. American Educational Company. December 25, 1909. p. 248 – via Google Books.

- Hedreen, Siri (April 28, 2021). "Timeline: The rise and fall of Benson". Alexander City Outlook (article and image carousel). Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- "Kowaliga, Ala. Negro Community, Does Unique Work". The Tennessean. February 25, 1912. p. 28. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- Sznajderman, Michael; Atkins, Leah Rawls (Spring 2005). "William Benson and the Kowaliga School". Alabama Heritage. No. 76. The University of Alabama.

- Morris, Bilal G. (February 14, 2022). "The Black Town Under Lake Martin: A Father & Son's Dream Of Greatness". NewsOne. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- Hamilton, Green Polonius (December 25, 1911). Beacon Lights of the Race. E. H. Clarke & brother. pp. 462– – via Google Books.

- Nolen, Russell (August 2, 1990). "Lake Martin legend behind Hank's song". The Anniston Star. p. 24. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

You've beard about Kowaliga. Hank Williams made him famous in the song...

- Hedreen, Siri (April 28, 2021). "Two amateur historians are putting the 'drowned town' of Benson back on the map". Alexander City Outlook. Alex City Outlook. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- "John Benson". Russell Lands History. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- "In "Black Belt" of Alabama". The Berkshire Eagle. December 22, 1903. p. 9. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- Barrows, Isabel C. (1902). "A Fair County and a County Fair". Christian Register and Boston Observer. Vol. 81. p. 1447.

- Bailey, Richard (1999). They Too Call Alabama Home: African American Profiles, 1800-1999. Pyramid Pub. pp. 37, 429. ISBN 978-0-9671883-0-0.

- Owen, Thomas McAdory (1921). History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography. S. J. Clarke publishing Company. pp. 822, 828.

- Walls, Peggy Jackson (July 19, 2021). Lost Towns of Central Alabama. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781439673058 – via Google Books.

- Bieze, Michael (2008). Booker T. Washington and the Art of Self-representation. Peter Lang. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-1-4331-0010-9.

- "Negro Education Called a Trust". New-York Tribune. May 23, 1915. p. 11. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute

- Who's Who in Colored America. Who's Who in Colored America Corporation. 1927. p. 11.

- Annual Report of the American Missionary Association. American Missionary Association. The Association. 1910. p. 52.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Negro President Ousted". The New York Times. June 5, 1915. p. 5. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- "Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Alabama". Alabama Supreme Court. December 25, 1920 – via Google Books.

- Schafer, Elizabeth D. (November 1, 2002). Lake Martin, Alabama's Crown Jewel. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-7385-2390-3.

While he stayed at Lake Martin in August 1952 to recuperate...he asked Rose to travel to Alabama to compose the music. Rose retitled William's Kowaliga as "Kaw-Linga" and focused the story on the dime store Indian

- "Kowaliga Restaurant, a Lake Martin landmark that dates back to the early 1950s, gets ready to reopen". al. April 23, 2013.

Williams, an Alabama native who grew up in Georgiana and often vacationed in a cabin on Lake Martin, recorded the song in 1952

- Duncan, Andy (June 2, 2009). Alabama Curiosities: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities & Other Offbeat Stuff. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4617-4728-4.

...who told Hank about Kowaliga, a long gone Creek Indian town in the area

- Huntley, Harold (March 20, 1953). ""Kowaliga Day" Program is 'Success'". Alexander City Outlook. p. 1. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

...the place where the hillbilly singer got inspiration for the tune

Further reading

- The 17th Annual Report of the Kowaliga School (Incorporated, Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute) (catalogue with images). Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute. 1912.

- "Kowalinga: A Community with A Purpose". The Negro in the Cities of the North. Survey Associates, Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. Publication Committee. New York City, NY. 1905.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - Hamilton, Green Polonius (December 25, 1911). "William E. Benson". Beacon Lights of the Race. E. H. Clarke & brother. p. 462.

- Cox, Donna L. (Fall 2007). "Images of Kowaliga". Alabama Heritage Magazine. Vol. 86. University of Alabama.

External links

Media related to Kowaliga, Alabama at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kowaliga, Alabama at Wikimedia Commons- Carnegie Gifts and Grants to Kowaliga Academic and Industrial Institute, Alabama (1909), from Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University