Beonna of East Anglia

Beonna (also known as Beorna[note 1]) was King of East Anglia from 749. He is notable for being the first East Anglian king whose coinage included both the ruler's name and his title. The end-date of Beonna's reign is not known, but may have been around 760. It is thought that he shared the kingdom with another ruler called Alberht and possibly with a third man, named Hun. Not all experts agree with these regnal dates, or the nature of his kingship: it has been suggested that he may have ruled alone (and free of Mercian domination) from around 758.

| Beonna | |

|---|---|

Coin of Beonna, now in the British Museum | |

| King of the East Angles | |

| Reign | 749 – around 760 jointly with Alberht and possibly Hun |

| Predecessor | Ælfwald |

| Successor | Æthelred I |

Little is known of Beonna's life or his reign, as nothing in written form has survived from this period of East Anglian history. The very few primary sources for Beonna consist of bare references to his accession or rule written by late chroniclers, that until quite recently were impossible to verify. Since 1980, a sufficient number of coins have been found to show that he was indeed a historical figure. They have allowed scholars to make deductions about economic and linguistic links that existed between East Anglia and other parts of both England and northern Europe during his reign, as well as aspects of his own identity and rule.

Background

In contrast to the kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex, little reliable evidence about the kingdom of the East Angles has survived. The historian Barbara Yorke has maintained that this is due to the destruction of the kingdom's monasteries and the disappearance of both of the East Anglian Episcopal sees, which were caused by Viking raids and later settlement.[3]

Ælfwald of East Anglia died in 749 after ruling for thirty-six years.[4] During Ælfwald's rule, his kingdom enjoyed sustained growth and stability, albeit under the senior authority of the Mercian king Æthelbald,[5] who ruled his kingdom from 716 until he was murdered by his own men in 757.[6] Ælfwald was the last of the Wuffingas dynasty, who had ruled East Anglia since the 6th century. A pedigree in the Anglian collection that lists Ælfwald and his descendants includes many earlier Wuffingas kings.

Identity and joint rule

The identification of Beonna as a king of the East Angles is based upon a few written sources. One source is a statement in the twelfth-century Historia Regum, that after Ælfwald's death, "regnum ... ... hunbeanna et alberht sibi diviserunt" ('Hunbeanna and Alberht divided the kingdom of the East Angles between themselves'). The Historia Regum is believed to have been compiled by Symeon of Durham, but it is now generally accepted that much of it was written by Byrhtferth of Ramsey around the end of the 10th century.[7][note 2] Another source is a passage in the 12th-century Chronicon ex chronicis, once thought to have been written by Florence of Worcester, which stated that "Beornus" was king of the East Angles.[note 3] A third source is a regnal list in the Chronicon ex chronicis which states that "Regnante autem Merciorum rege Offa, Beonna regnavit in East-Anglia, et post illum Æthelredus" ('During the reign of Offa, king of the Mercians, Beonna reigned in East-Anglia, and after him Æthelred ...').[9][10][11][12][note 4]

The annal for 749 in The Flowers of History, written by the chronicler Matthew Paris in the 13th century, also relates that "Ethelwold, king of the East Angles, died, and Beonna and Ethelbert divided his dominions between them".[13] The historians H. M. Chadwick and Dorothy Whitelock both suggested that the name Hunbeanna should be divided into two names, Hun and Beanna, and that a tripartite division of the kingdom might have existed. According to Steven Plunkett, the name Hunbanna may have been created by means of a scribal error.[12]

The kingdom might never have been ruled jointly by Alberht and Beonna. It is generally accepted that Alberht and the later Æthelberht II, who ruled East Anglia until his death in 794, are different kings,[14] but the historian D. P. Kirby has identified them as being one person. According to Kirby, Beonna might have ascended the throne in around 758 and the issuing of his coins could indicate that East Anglia broke free of Mercian domination for a time, so linking Beonna's reign with the eventual disintegration of Mercian hegemony that occurred after Æthelbald's death.[15]

The diathematic element 'Hun'

The recognition of Beonna as a historical figure leaves the 'Hun' element in the word Hunbeanna detached. Beanna is itself a hypocoristic form of a two-part name,[16] and the 'nn' in the name has been interpreted as representing a geminate consonant.[17]

Hun is familiar in 8th- and 9th-century England, for instance as part of a name with two elements.[18] During the 9th century there were East Anglian bishops of Helmham named Ælfhun, Hunferthus and Hunbeorht and a bishop of Worcester called Æthelhun. Hun also occurred as part of a moneyer's name. There are several placenames in England that contain the term as a personal name element, such as Hunsdon, Hertfordshire and Hunston, West Sussex (but not Hunston, Suffolk).[19] It is possible that Hun was a historical figure, whose name was run together with Beonna's by a scribe.

An alternative theory is that the Latin annal that mentioned Hunbeanna was derived from an Old English source and that the translator scribe misread the opening word here for part of the name of Beonna. "Her" – 'in this year' – is the usual opening for an Old English annal and the typical form of the letter 'r' might easily be misread for an 'n'.

Beornred of Mercia

Charles Oman proposed that Beornred, who in 757 emerged for a short time as ruler of Mercia before being driven out by Offa,[note 5] could be the same person as Beonna.[21] An alternative theory suggests that Beonna and Beornred may perhaps have been kinsmen from the same dynasty with ambitions to rule in both Mercia and East Anglia.[22] No known member of the Wuffingas dynasty had a name commencing with B, but several Mercian rulers, including Beornred, used the letter.[23]

In 1996, Marion Archibald and Valerie Fenwick proposed an alternative hypothesis, based on the evidence of East Anglian coins and post-Conquest documents. Acknowledging that Beonna and Beornred were the same person, they suggested that after Ælfwald's death in 749, Æthelbald of Mercia installed Beornred/Beonna to rule northern East Anglia and Alberht (who probably belonged to the Wuffingas dynasty) to rule in the south. According to Archibald and Fenwick, after Æthelbald was murdered in 757, Beornred/Beonna became king of Mercia, during which his coinage was increased in East Anglia, perhaps to meet “military requirements”. Then, after a reign of only a few months, he was deposed by Offa and forced to flee from him back into East Anglia. Alberht, who had attempted to re-establish East Anglia as an independent kingdom and rule alone, and had succeeded for a short time, was deposed by Beornred/Beonna when he arrived as an exile in about 760. Soon afterwards, Offa asserted his authority over the East Angles in around 760-5 and removed Beonna.[24]

Coinage

Anglo-Saxons kings produced coins from the 620s onwards, initially in gold, but then in electrum (an alloy of gold and silver) and eventually pure silver. Little is known of the organisation of coinage during the reign of Beonna, but it can be presumed that the moneyers who struck coins during this period acted under the auspices of the king, who would to some extent have supervised the design of his coins.[25] A growing shortage of available bullion in north-western Europe during the first half of the 8th century was probably the main cause for a deterioration in the proportion of precious metal found in locally produced sceattas. In around 740, Eadberht of Northumbria became the first king to respond to this crisis by issuing a remodelled coinage, of a consistent weight and a high proportion of silver, which eventually replaced the debased currency. Other kings followed his example, including Beonna and the Frankish king Pepin the Short, who appears to have been strongly influenced by the newly introduced coins of both Beonna and Eadberht.[26]

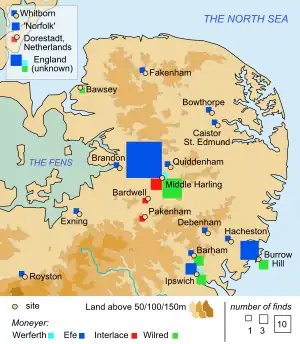

Examples of Beonna's coins are known from two separate hoards, as well as from a number of individual finds. Until 1968, only five of his coins were known. Several more coins came to light over the next decade, before a hoard of sceattas and other coins were discovered in 1980 at Middle Harling, north-east of Thetford and close to the border between the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. In all, fifty-eight coins have been excavated from Middle Harling, fourteen were found at Burrow Hill (Suffolk) and thirty-five from other places in East Anglia and elsewhere.[27] Over a hundred 'Beonnas' are now known:[28] most of them have been acquired by the British Museum.[29]

Beonna was the first of the East Anglian kings whose coinage named both the ruler and his title. His coins are larger than the earlier sceattas, but are small when compared with the pennies produced in Anglo-Saxon England several decades later. As a whole, they provide an important dateable runic corpus and may reflect a distinctive East Anglian preference for runic lettering.[30][31] Beonna had three moneyers whose names are known: Werferth, Efe and Wilred. The coins struck by Werferth are considered to be the earliest. His coins and those struck under the authority of Eadberht both contained 70% silver and were similar in type and detail, which suggests the possibility of producing a chronology for Beonna's coins, using the established sequence for the Northumbrian coins of Eadberht. However, as Eadberht's reign began in 738, several years before Beonna became king in East Anglia, the coins cannot be related to each other closely enough to construct a reliable chronology.[32]

Produced later than Werferth's coins are those by Efe: these, by far the most numerous, have dies which change in time. Distribution analysis suggests that Efe's mint was possibly located in northern Suffolk or southern Norfolk. It is possible that the name of the village of Euston, Suffolk, a little southeast of Thetford, is derived from Efe.[33]

Efe's obverse dies show the king's name and title, usually spelt with a mixture of runes and Latin script, with some aspects of the coins occasionally ill-drawn or omitted altogether. The king's name is generally arranged around the central motif of a pellet (or a cross) within a circle of pellets: this layout probably derived from Northumbrian coins. The reverse dies consisted of a cross and the letters E F E, placed in four sectors that were divided off by lines. It can be shown that Efe did not use his dies in any particular or consistent order. Calculations have been made that suggest that few of his dies remain undiscovered.[34]

The coins struck by Beonna's last known moneyer, Wilred, are so different from Efe's that it is highly unlikely that they were produced at the same mint or at the same time.[35] It can also be assumed that Wilred is the same moneyer who struck coins for Offa of Mercia,[note 6] possibly at Ipswich. Wilred's coins can be used to demonstrate that Offa's influence over the East Angles occurred at an earlier date than has previously been supposed, but are of little use in determining a secure chronology for Beonna's reign.[36] Wilred's name is always depicted in runes. Nearly all his reverse dies have two crosses placed between the elements of his name (+ wil + red): most of the obverse dies show crosses and the king's name in a similar design, but also include an extra rune.[37] This unique rune, similar to ᚹ, possibly meant walda ('ruler').[2]

One type of coin for Beonna has no named moneyer and depicts an interlace motif on its reverse. A specimen of this type (now lost) was found at Dorestad, which was during Beonna's time an important trading centre: these coins resemble Frankish or Frisian deniers that were issued from the Maastricht area during this period.[38]

Beonna's rule coincided with the anointing of Pippin III as king of the Franks after 742 and the subsequent disempowerment of the Merovingian dynasty, and also with the martyrdom of Saint Boniface and his followers in Frisia in 754.[39] Two coins use a runic 'a' in the name Beonna; the runic 'a' has only been found elsewhere in Frisia, suggesting that there were both trading and language links between Frisia and East Anglia during the 8th century.[2]

Notes

- According to Marion Archibald, alternatives include Beorna, Beanna, Beornna, Hunbearn and Benna, all of which she considers to have been acceptable variations of one name, a hypocoristic form of Beorn-, which was a common element in Old English personal names.[1][2]

- The relevant passage in the Historia Regum (folio 62R and folio 62V) can be viewed online at Parker Library on the Web.

- The relevant passage in the Chronicon ex chronicis (Manuscript 157, page 277) can be viewed online at Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. The paragraph reads, "Cuthberhtus Doruvernensis archiepiscopus VII. kal. Novembris [26 Oct.] vitæ modum fecit. His temporibus, Orientalibus Saxonibus Swithredus, Australibus Saxonibus Osmundus, Orientalibus Anglis Beorna, reges præfuerunt."[8]

- The relevant passage in the Chronicon ex chronicis (Manuscript 157, page 49) can be viewed online at Early Manuscripts at Oxford University.

- Beornred succeeded to the Mercian throne upon the death of Æthelbald. His relationship to his predecessors in unclear, although he may have been descended from Penda.[20]

- The assumption that Wilred made coins for both kings contrasts with the view of Valerie Fenwick, who describes Wilred's single Offa penny as a continental imitation and who disputes that either Wilred was sent by Offa to work as Beonna's moneyer, or that he worked in Mercia whilst Beonna ruled East Anglia as a sub-king.[2]

Footnotes

- Archibald, The Coinage of Beonna, pp. 39–40.

- Fenwick, Insula de Burgh, p. 48.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p. 58.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 63.

- Archibald, The Coinage of Beonna, p. 23.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 112.

- Lapidge, Anglo-Latin Literature 600-899, p. 32.

- Florence of Worcester, Thorpe (ed.), Chronicon ex chronicis, p. 57.

- Pagan, A New Type for Beonna, p. 14.

- Forester, Thomas (translator), Florence of Worcester's Chronicle, p. 445.

- Florence of Worcester, Thorpe (ed.), Chronicon ex chronicis, p. 261.

- Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, p. 155.

- Matthew of Paris (trans. Yonge), The Fowers of History, p. 361.

- Archibald Cowell and Fenwick, A Sceat of Æthelberht, pp. 9–10.

- Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 115.

- Page, An Introduction to English Runes, p. 129.

- Hegedüs and Fodor, English Historical Linguistics, p. 83.

- Hill and Worthington, Aethelbald and Offa, p. 130.

- Ekwall, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names, p. 257.

- Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 134.

- Archibald, The Coinage of Beonna, p. 33.

- Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, p. 160.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 67, 119.

- Archibald Cowell and Fenwick, A Sceat of Æthelberht, p. 12.

- Page, An Introduction to English Runes, p. 117–8.

- Naismith, Money and Power in Anglo-Saxon England, p. 97.

- Archibald, Cowell and Fenwick, A Sceat of Ethelbert I, p. 5.

- Archibald, Cowell and Fenwick, A Sceat of Ethelbert I, p. 1.

- Archibald, The Coinage of Beonna, p. 10.

- Page, An Introduction to English Runes, p. 215.

- Brown and Farr, Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, p. 214.

- Archibald, The Coinage of Beonna, p. 31.

- Archibald, The Coinage of Beonna, p. 30.

- Archibald, The Coinage of Beonna, pp. 19–23.

- Archibald, The Coinage of Beonna, p. 24.

- Archibald, The Coinage of Beonna, p. 32.

- Archibald, The Coinage of Beonna, p. 38.

- Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, p. 158.

- Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, p. 159.

References

- Archibald, Marion M. (1985). "The Coinage of Beonna in the light of the Middle Harling Hoard" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 55: 10–54.

- Archibald, M.M.; Cowell, M.R.; Fenwick, V.H. (1996). "A sceat of Ethelbert I of East Anglia and recent finds of coins of Beonna" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 65: 1–19.

- Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (2001). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

- Florence of Worcester (1848). Thorpe, Benjamin (ed.). Chronicon ex chronicus (Volume 1). London. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Fenwick, V.H. (1984). "Insula de Burgh: Excavations at Burrow Hill, Butley, Suffolk 1978–1981" (PDF). Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History. 3: 35–54.

- Forester, Thomas (translator) (1854). The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester, with the Two Continuations. London: Bohn. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24211-8.

- Lapidge, Michael (1996). Anglo-Latin Literature 600-899. London: Hambleton Press. ISBN 1-85285-011-6.

- Matthew of Paris (Matthew of Westminster) (trans. by Yonge, C. D.) (1858). The Flowers of History (volume 1). London: Bohn.

- Naismith, Rory (2012). Money and Power in Anglo-Saxon England: The Southern English Kingdoms 757-863. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00662-1.

- Pagan, H. E. (1968). "A New Type for Beonna" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 37: 10–15.

- Page, R.I. (2006). An Introduction to English Runes. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-946-X.

- Plunkett, Steven (2005). Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3139-0.

- Yorke, Barbara (2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16639-X.

- Rogerson, Andrew (1995). A Late Neolithic, Saxon and Medieval Site at Middle Harling, Norfolk, East Anglian Archaeology 74. London & Dereham: British Museum & Norfolk Museums Service. ISBN 0-905594 17 7.

External links

- Beonna 7 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England; see also Beonna 6

- Search result for 'Beonna' in the British Museum's collection database.

- Searchable database of the Corpus of Early Mediaeval Coin Finds, and Sylloge of Coins of the British Isles (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge).

- Uploaded image of an Interlace coin on Flickr.

- Parker Library on the Web - an interactive web site in which many of the manuscripts in the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge - including the Historia Regum - can be viewed.

- Early Manuscripts at Oxford - a resource containing high quality images of over 80 mediaeval manuscripts.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)