Berbice

Berbice is a region along the Berbice River in Guyana, which was between 1627 and 1792 a colony of the Dutch West India Company and between 1792 and 1815 a colony of the Dutch state. After having been ceded to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in the latter year, it was merged with Demerara-Essequibo to form the colony of British Guiana in 1831. It became a county of British Guiana in 1838 till 1958. In 1966, British Guiana gained independence as Guyana and in 1970 it became a republic as the Co-operative Republic of Guyana.

Kolonie Berbice (1627–1803) Colony of Berbice (1803–1831) County of Berbice (1838–1958) Berbice | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1627–1831 1838–1958 | |||||||||

Flag (1627–1792) Flag (1803–1831) | |||||||||

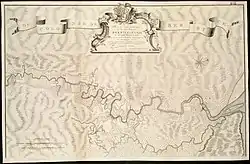

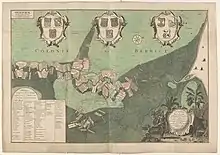

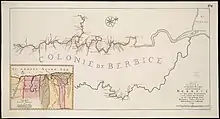

Berbice around 1780. | |||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||

| Capital | Fort Nassau (1627–1785) Fort Sint Andries (1785–1815) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Dutch, Berbice Creole Dutch, English, Guyanese Creole, Guyanese Hindustani (Nickerian-Berbician Hindustani), Tamil, South Asian languages, African languages, Akawaio, Macushi, Waiwai, Arawakan, Patamona, Warrau, Carib, Wapishana, Arekuna, Portuguese, Spanish, French, Chinese | ||||||||

| Religion | Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Afro-American religions, Traditional African religions, Indigenous religions | ||||||||

| Governing company | |||||||||

• 1627–1712 | Van Peere family | ||||||||

• 1714–1815 | Society of Berbice | ||||||||

• 1627 | Abraham van Peere | ||||||||

• 1789–1802 | Abraham Jacob van Imbijze van Batenburg | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established as a Dutch West India Company colony | 1627 | ||||||||

| November 1712–24 October 1714 | |||||||||

| 24 October 1720–1821 | |||||||||

| 24–27 February 1781 | |||||||||

| 22 January 1782 | |||||||||

| 1783 | |||||||||

• Colony of the Dutch Republic | 1 January 1792 | ||||||||

| 27 March 1802 | |||||||||

| 20 November 1815 | |||||||||

| 21 July 1831 | |||||||||

• County of Berbice | 1838 | ||||||||

• Merged into the new regions | 1958 | ||||||||

| Currency | Spanish dollar, Dutch guilder, British Guiana dollar, British West Indies dollar | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Guyana | ||||||||

| |||||||||

After being a hereditary fief in the possession of the Van Peere family, the colony was governed by the Society of Berbice in the second half of the colonial period, akin to the neighbouring colony of Suriname, which was governed by the Society of Suriname. The capital of Berbice was at Fort Nassau until 1790. In that year, the town of New Amsterdam, which grew around Fort Sint Andries, was made the new capital of the colony.

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

| History of Guyana | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

Berbice was settled in 1627 by the businessman Abraham van Peere from Vlissingen, under the suzerainty of the Dutch West India Company. Until 1714, the colony remained the personal possession of Van Peere and his descendants. Little is known about the early years of the colony, other than that it succeeded in repelling an English attack in 1665 in the Second Anglo-Dutch War.[1][2] The colony was a family affair who owned all the plantations on the Berbice River, though they did allow a couple of sugar planters to settle on the Canje River.[3]

A dispute arose between the Second Dutch West India Company, which was founded to succeed the First Dutch West India Company that went bankrupt in 1674, and the Van Peere family, because the family wanted the colony as an immortal loan as agreed with the first Company.[4] This was resolved when on 14 September 1678 a charter was signed which established Berbice as a hereditary fief of the Dutch West India Company, in the possession of the Van Peere family.[5]

In November 1712, Berbice was briefly occupied by the French under Jacques Cassard, as part of the War of the Spanish Succession. The Van Peere family did not want to pay a ransom to the French to free the colony, and in order to not let the colony cede to the French, the brothers Nicolaas and Hendrik van Hoorn, Arnold Dix, Pieter Schuurmans, and Cornelis van Peere, paid the ransom of ƒ180,000 in cash and ƒ120,000 in sugar and enslaved people on 24 October 1714, thereby acquiring the colony.[6]

Society of Berbice

In 1720, the five owners[7] of the colony founded the Society of Berbice, akin to the Society of Suriname which governed the neighbouring colony, to raise more capital for the colony. The Society was a public company listed on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.[8] In the years following, Berbice's economic situation improved, consisting of 12 plantations owned by the society, 93 private plantation along the Berbice River, and 20 plantations along the Canje River.[9]

In 1733, 25 to 30 houses were built around Fort Nassau to house the craftsmen. The next year an inn was added. The village was named New Amsterdam (Dutch: Nieuw Amsterdam).[10] In 1735, a school master was hired to teach the white children.[11] There were medical doctors stationed in New Amsterdam and Fort Nassau, and six local doctors were assigned to the plantations. Epidemics remained a frequent problem in the colony resulting in many deaths.[12]

The religion in the colony was Calvinism.[13] In 1735, a minister was installed in Fort Nassau, but after a personal conflict with the governor, he was transferred to Wiruni Creek.[11] Catholics and Jews were not allowed to become planters or have a government function.[14] In 1738, two missionaries of the Moravian Church had been invited by a planter to teach the people he enslaved. They were treated with suspicion, and received several official warnings. In 1757,[15] the missionaries left, and joined the congregation at the village of Pilgerhut founded in 1740 outside the plantation area, where they lived with 300 Arawak.[16]

The colony had peace and trade treaties with the local Amerindians. This colony did not intervene in wars between the tribes, and no Amerindian was allowed to be taken into slavery unless they were sold by the Kalina or the Arawak and captured from the interior of the country.[17]

Berbice was supposed to be guarded by 60 soldiers in Fort Nassau, and another 20 to 30 soldiers in other locations.[18] Even when not under attack, wars often caused supply problems. In 1670s, the colony had not been supplied for 17 months,[19] and neutrality as during the Seven Years' War could not prevent supply shortages.[20]

Slave Uprising

The relatively sound economic situation of the colony was dealt a severe blow when a slave uprising broke out under the leadership of Coffy in February 1763.[21] The enslaved people captured the south of the colony while the whites, who were severely outnumbered, tried to hang on the north. The uprising went on until well into 1764, with Coffy naming himself governor of Berbice. Only with the use of brute force and military aid by neighbouring colonies and the Netherlands was governor Wolfert Simon van Hoogenheim able to finally suppress the uprising, and restore the colony to Dutch rule.[9][22]

The uprising led to a steep population decline,[23] abandonment and destruction of many plantations, and serious financial problems for the Society.[24] Fort Nassau had been set on fire to prevent it falling into enemy hands.[25] In 1785 the village was abandoned in favour of Fort Sint Andries, situated more downstream, at the confluence of the Canje River. The new village was again named New Amsterdam, and is still known by that name in contemporary Guyana.[26]

Capture by Britain and subsequent merging into British Guiana

On 27 February 1781, British forces occupied Berbice and neighbouring Demerara and Essequibo as part of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, because 34 out of 93 plantations in Berbice were under British ownership.[27] In January 1782, the colonies were recaptured by the French, who were allied with the Dutch, and who subsequently restored the colonies to Dutch rule with the Treaty of Paris of 1783.[28]

The colony was on 22 April 1796 again captured by Britain, however this time without a fight. A deal was struck with the colony: all laws and customs could remain, and the citizens were equal to British citizens. Any government official who swore loyalty to the British crown could remain in function.[29] Abraham van Batenburg decided to remain governor. Many plantation owners from Barbados settled in the colony, doubling the slave population.[30] The British now remained in possession of the colony until 27 March 1802, when Berbice was restored to the Batavian Republic under the terms of the Treaty of Amiens.[31] In 1803, there was a mutiny of soldiers who complained about the rations. They occupied Fort Sint Andries, and raised the Union Jack with a piece of meat on top. The remaining soldiers aided by Suriname and the Amerindians put down the revolt, and executed five soldiers.[32]

In September 1803 the British occupied the territory again, this time for good,[33] and once again without a fight.[34] Abraham van Batenburg, who had been exiled to Europe in 1803, returned for his second term as governor.[35] In the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, the colony was formally ceded to the United Kingdom,[31] and with the ratification of this treaty by the Netherlands on 20 November 1815, all Dutch legal claims to the colony were rescinded.[36] The plantations and the enslaved people of the Society of Berbice remained under their ownership,[4] but they had already made a decision to sell their possessions in 1795,[37] and they closed their offices in 1821.[4]

In 1812, the colonies of Demerara and Essequibo had been merged into the colony of Demerara-Essequibo.[31] As part of the reforms of the newly acquired colonies on the South American mainland, the British merged Berbice with Demerara-Essequibo on 21 July 1831, forming the new crown colony of British Guiana, now Guyana.[33]

In 1838, Berbice was made one of the three counties of Guiana, the other two being Demerara and Essequibo.[38] In 1958, the county was abolished when Guiana was subdivided into districts.[38]

Legacy

Historical Berbice was split in 1958[39] to make new Guyanese administrative regions and the name is preserved in the regions of East Berbice-Corentyne, Mahaica-Berbice, and Upper Demerara-Berbice.[38]

Berbice Creole Dutch, a Dutch creole language based on the lexicon and grammar of the West African language Ijo, was spoken until well into the 20th century. In 2005, the last known speaker died. The language was declared extinct in 2010.[40]

Administration

Commander of Berbice

- Matthijs Bergenaar (1666–1671)

- Cornelis Marinus (1671–1683)

- Gideon Bourse (1683–1684)

- Lucas Coudrie (1684–1687)

- Matthijs de Feer (1687–1712)

- Steven de Waterman (1712–1714)

- Anthony Tierens (1714–1733)

Governors of Berbice

- Bernhardt Waterman (1733–1740)[41]

- Jan Andries Lossner (1740–1749)[41]

- Jan Frederik Colier (1749–1755)[41]

- Hendrik Jan van Rijswijck (1755–1759)[41]

- Wolfert Simon van Hoogenheim (1760–1764)[41]

- Johan Heijlinger (1765–1767)[41]

- Stephen Hendrik de la Sabloniere (1768–1773)

- Johan Christoffel de Winter (1773–1774)

- Isaac Kaecks (1774–1777)

- Peter Hendrik Koppiers (first term) (1778–27 February 1781)

- Robert Kingston (27 February 1781 – 1782)

- Louis Antoine Dazemard de Lusignan (1782)

- Armand Guy Simon de Coëtnempren, Count of Kersaint (1782)

- Georges Manganon de la Perrière (1783–1784)

- Peter Hendrik Koppiers (second term) (1784–1789)

- Abraham Jacob van Imbijze van Batenburg (first term, acting until 1794) (1789–1796)

- J. C. W. Herlin and G. Kobus (acting) (27 March 1802 – September 1803)

Lieutenant Governor of Berbice

- Abraham Jacob van Imbijze van Batenburg (1796–1802)[30]

- Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Nicholson (1803–1804)[42]

- Abraham Jacob van Imbijze van Batenburg (second term) (June 1804 – 1805)[42]

- Brigadier-General James Montgomerie (1805–1806)

- Henry William Bentinck (1806–1807)

- Brigadier-General Robert Nicholson (1807–1808)

- Major-General Samuel Dalrymple (1808–1809)

- Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew Ross (1808–1809)

- Henry William Bentinck (1809–1810)

- Major-General Samuel Dalrymple (1810)

- Henry William Bentinck (1810–1812)

- Major-General Hugh Lyle Carmichael (1812–1813)

- Colonel Edward Codd (1813)

- Major-General John Murray (1813–1815)

- Henry William Bentinck (1814–1815)

- Colonel Edward Codd (1815)

- Henry William Bentinck (1815–1820)

- Major-General John Murray (1815–1824)

- Henry Beard (1821–21 July 1831)

Notable people

- Cheddi Jagan (1918–1997), Father of the Nation and former President of Guyana

See also

Notes

- Hartsinck 1770, p. 293

- Beyerman 1934, p. 313

- Netscher 1888, p. 155.

- Dutch National Archive – Inventaris van het archief van de Sociëteit van Berbice, (1681) 1720–1795 (1800)

- Hartsinck 1770, pp. 294–298

- Hartsinck 1770, pp. 299–304

- Netscher 1888, p. 392:Both brothers shared a quarter and therefore could only cast one vote

- Beyerman 1934, pp. 313–314.

- Beyerman 1934, p. 314

- Netscher 1888, pp. 174–175.

- Netscher 1888, p. 177.

- Netscher 1888, p. 189.

- Netscher 1888, p. 188.

- Netscher 1888, p. 184.

- H.G. Steinberg (1933). Ons Suriname de Zending der Evangelische Broedergemeente in Nederlandsch Guyana. p. 71. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Netscher 1888, pp. 185–186.

- Netscher 1888, p. 187.

- Netscher 1888, p. 174.

- Netscher 1888, p. 151.

- Husani Dixon. "The causes of the 1763 rebellion". Academia.edu. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- "Berbice Uprising in 1763". Slavenhandel MCC (Provincial Archives of Zeeland). Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Kars 2016, pp. 39–69.

- Hartsinck 1770, p. 538.

- Netscher 1888, p. 256.

- "The Collapse of the Rebellion". Guyane.org. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Cofona.org – From a Glorious past to a Promising Future: A History of New Amsterdam Archived 2011-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Smith 1956, Chap. II.

- Edler 2001, p. 185

- A.N. Paasman (1984). "Reinhart: Nederlandse literatuur en slavernij ten tijde van de Verlichting". Digital Library for Dutch Literature. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "BERBICE AT THE END OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY". Guyana.org. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Schomburgk 1840, p. 86.

- Netscher 1888, pp. 283–284.

- "37. The Beginning of British Guiana". Guyana.org. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Netscher 1888, p. 284.

- Netscher 1888, p. 286.

- "Berbice". British Empire. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- "Dutch Series Guyana" (PDF). National Archive (in Dutch). p. 11. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Regions of Guyana at Statoids.com. Updated 20 June 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "ADMIN REGIONS DETAILED – GUYANA LANDS AND SURVEYS COMMISSION'S FACT PAGE ON GUYANA". Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- "Onze Taal. Jaargang 79". Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). 2010. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Hartsinck 1770, p. 520.

- "Berbice Administrators". British Empire. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

References

- Beyerman, J. J. (1934). "De Nederlandsche Kolonie Berbice in 1771". Nieuwe West-Indische Gids (in Dutch). 15 (1): 313–317.

- Edler, F. (2001) [1911], The Dutch Republic and The American Revolution, Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 0-89875-269-8

- Hartsinck, J.J. (1770), Beschryving van Guiana, of de wilde kust in Zuid-America, Amsterdam: Gerrit Tielenburg

- Kars, Marjoleine (Feb 2016). "Dodging Rebellion: Politics and Gender in the Berbice Slave Uprising of 1763". American Historical Review. 121 (1): 39–69.

- Netscher, Pieter Marinus (1888). Geschiedenis van de koloniën Essequebo, Demerary en Berbice, van de vestiging der Nederlanders aldaar tot op onzen tijd (in Dutch). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Schomburgk, Sir Robert H. (1840). A Description of British Guiana, Geographical and Statistical: Exhibiting Its Resources and Capabilities. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co. ISBN 978-0714619491.

- Smith, Raymond (1956). "History: British Rule Up To 1928". The Negro Family in British Guiana. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Limited. ISBN 0415863295. Archived from the original on 2015-01-08. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

_(2022).svg.png.webp)