Bidston Hill

Bidston Hill is 100 acres (0.40 km2) of heathland and woodland containing historic buildings and ancient rock carvings, on the Wirral Peninsula, near the Birkenhead suburb of Bidston, in Merseyside, England. With a peak of 231 feet (70 m), Bidston Hill is one of the highest points on the Wirral.[1][2] The land was part of Sir Robert Vyner's estate[3] and purchased by Birkenhead Corporation in 1894 for use by the public.[4]

| Bidston Hill | |

|---|---|

Bidston Hill from the tower of St Oswald's | |

| |

| Type | Common |

| Location | Bidston, Merseyside |

| Coordinates | 53.397°N 3.075°W |

| Area | 100 acres (0.40 km2) |

| Operated by | Metropolitan Borough of Wirral |

| Open | All year |

| Status | Open |

Etymology

Bidston Hill bears the name of the village of Bidston, the name being recorded in 1260 as Bedistan; origin possibilities include variations of the Old English name 'Beda' or 'Byddi' combined with ton, or from 'bytle stan', meaning a dwelling on a rock, or possibly a reference to a 'bidding-stone' for a venerated Saxon.[5][6]

Geography

Bidston Hill is in the north-east of the Wirral Peninsula and reaches 231 feet (70 m) at its highest point.[1]

Geology

The exposed ridgeline along Bidston Hill is composed of brown, buff and grey Delamere Pebbly Sandstone of fluvial origin, part of the Helsby Sandstone Formation within the Sherwood Sandstone Group. This may be equatable with the Lower Keuper described in older sources regarding the hill. Nearer to Bidston Hall are types of Thurstaston Soft Sandstone of Aeolian type.[7][8][9]

History

Ownership of Bidston Hill

As part of the manor of Bidston, Bidston Hill was within the barony of Dunham Massey. The clear association with the Mascys (Masseys) remained until the land was sold around the mid-14th century to Henry, 4th Earl of Lancaster. This purchase was in proxy for the LeStranges, and on the Earl's death Roger LeStrange assumed possession of the Dunham barony. Legal claims by the descendents of Hamon Mascy V were raised against the LeStrange ownership but the status quo remained and on 24 June 1347 John Le Strange, son of Roger, sold the manor of Bidston and other lands to Sir John Stanley.[10][11]

In 1407 under Stanley's ownership a stone-walled enclosure was made on the west and north-west of Bidston Hill for the purpose of retaining deer. This would later be known as the Penny-a-day dyke.[10]

The Stanley descent persisted and post-1627 James Stanley, 7th Early of Derby (known as Lord Strange) inherited the running and eventual ownership of the estate from his father the 6th Earl of Derby. Lord Strange was killed at Bolton while supporting King Charles II, and immediately the hill's ownership was brought into question, the estate having been sequestered by the state. His widower, the Countess Derby, pled for ownership of the estate (within that the hill) as it was part of her dowry. Another party, William Steele, was however able to acquire the land and he took possession in 1653. [10][11]

Steele's ownership lasted less than a decade and in 1662 Sir John King purchased the estate from him. It was in 1665 during Sir John's ownership that a survey map of the area was created. In 1676 Sir John died, his sons to inherit, and in 1680 Sir Robert Vyner gained the land's title by way of mortgage.[10] Sir Robert Vyner is notable as the maker of many of the Crown Jewels. The Vyner family remained in ownership of the hill until 1894 when it was sold to the Birkenhead corporation.[4] A plaque on Bidston windmill commemorates this event.[12]

Buildings

The hill has been the site of several notable buildings, including Bidston Windmill, which was a replacement for an earlier windmill destroyed by fire in 1791. The windmill was built in the late 18th century using roughcast render over stone or brick and it went on to grind wheat until 1875 when steam-powered milling started to be introduced. It was restored in 1894 and 1971. Additionally, Bidston Hill has a formerly operating lighthouse and observatory.[13][14]

Bidston Observatory was built in 1866 using local sandstone excavated from the site. One of its functions was to establish the exact time. Up to 18 July 1969, at exactly 1:00 p.m. each day, the 'One O'Clock Gun' overlooking the River Mersey near Morpeth Dock, Birkenhead, would be fired electrically from the Observatory.[15][13] In 1929 the work of the observatory was merged with the University of Liverpool Tidal Institute, being taken over in 1969 by the Natural Environment Research Council. The Research Council relocated the Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory to the University of Liverpool campus in 2004, and it is now known as the National Oceanography Centre, Liverpool.[16][17] The Joseph Proudman Laboratory building, which was located on the hill but separate from the observatory, was demolished in 2013.[18]

Maritime signalling

There has been a lighthouse on Bidston Hill since 1771. The first lighthouse was built by Liverpool's dockmaster William Hutchinson; it was designed to work in conjunction with Leasowe Lighthouse, forming a pair of leading lights enabling ships to avoid the sandbanks in the channel to Liverpool.[19]

Being more than two miles from the sea, a record unsurpassed by any other lighthouse[20], Bidston depended on a breakthrough in lighthouse optics, which came in the form of the parabolic reflector, developed by Hutchinson at the signals station on Bidston Hill. The reflector at Bidston Lighthouse was thirteen-and-a-half feet in diameter (probably the largest ever made for a lighthouse)[20] and the lamp consumed a gallon of oil every four hours.[21]

The present lighthouse was built in 1873 and was equipped with a large (first order) dioptric lens with vertical condensing prisms, manufactured by Chance Brothers of Birmingham.[22] It remained operational until sunrise on 9 October 1913. (By that time Leasowe Lighthouse had already been decommissioned: the line of approach taken by ships had altered due to shifting sandbanks, rendering the leading lights ineffective).

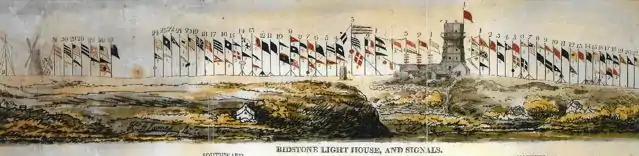

In addition to the lighthouse, Bidston Hill was once home to a flag signalling station which operated from the year 1763 to about 1840. When a known ship would approach, the related company flag would be raised in order to alert the relevant merchant house and dock workers in Liverpool of its impending arrival. At the systems height of operation there were over 100 flags that could be used and it was a popular visitor attraction. The scene of the signalling system and lighthouse has been the subject of artistic designs on pottery.[10][23][24][13]

The name Bidston Hill was born by a bark type ship built in Liverpool in 1866 by T. Royden and Sons and owned by the 'Sailing Ship Bidston Hill Company'. The 'Bidston Hill' was wrecked in 1905 off Isla de los Estados, near Cape Horn.[25][26]

Rock carvings

Close to information post 13 there is a 4+1⁄2-foot-long (1.4 m) carving of a sun goddess carved into the flat rock north-east of the Observatory, supposedly facing in the direction of the rising sun on Midsummer's Day and thought to have been carved by the Norse-Irish around 1000 AD. An ancient carving of a horse is on bare rock to the north of the Observatory, close to information post 10, with a later carving beneath of the Latin 'EQUINO'.[27]

Tunnels

During World War II, an air raid shelter was constructed at Bidston Hill. Today the tunnels are concealed for public safety.[28]

The Bidston Hill tunnel project was born in 1941 out of the devastating effects of the Luftwaffe blitz on Merseyside. Many infrastructure targets were hit, people killed and many more made homeless. The first week of May 1941 saw the peak of the attack, involving 681 Luftwaffe bombers, 2,315 high-explosive bombs and 119 other explosives. The raids put 69 out of 144 cargo berths out of action and inflicted 2,895 casualties, 1,741 of them fatalities.

Flora and fauna

Designated locally as a 'site of biological importance', Bidston Hill is recognised for its lowland heath habitat, mature deciduous and coniferous woodland, and scrub habitat. European gorse has established itself and the spread of trees and shrubs threatens the heathland. The woodland is a habitat for breeding birds such as greater spotted woodpecker, sparrowhawk, goldcrest and others. It is secondary in nature and dominated by Scots pine, English oak and beech from plantings in the 1800s. Some more recent areas are birch-predominant. Within the woods are specimens of hybrid rhododendron, a result of introduction in the Victorian era. Sycamore is also invasive.[29]

Minor areas of damp heath habitat, rare on the peninsula, can be found and support species such as Sphagnum bog-mosses, cross-leaved heath and purple moor grass. Additionally, peat hollows and areas of pooling give a home for wetland plants and there are some peripheral areas of acidic grassland.[29]

Meteorological observation and data

The observatory was noted by the Meteorological Committee of the Royal Society (1871) as providing weather information to Liverpool via telegraph on behalf of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board.[30]

The historic temperature recordings at Bidston Hill occurred at an elevation of 198 feet (60 m), higher than the nearby Hoylake station at 22 feet (10 m). Between the years 1920-49 the recorded mean annual temperature averaged at more than 49.3 °F (9.6 °C), with the mean of July being 60.25 °F (15.69 °C). Positioned on the exposed sandstone hill-top, the station on the hill averaged lower mean maximum temperatures between March and October than Macclesfield (500 feet (150 m)) or Bolton (342 feet (100 m)), and between May and August the temperatures also averaged lower than the station at Stonyhurst (377 feet (110 m))[31]

The station on Bidston Hill and the Hoylake station were a similar distance from the sea, but due to differences in elevation, the temperatures differed, with Hoylake having consistently higher monthly mean maximum averages. The difference between the mean maximums recorded was most minimal during December at 1.6 F and at its greatest in July and August (2.3 F). Additionally, Hoylake consistently had lower mean minimum temperatures due to the tendency of cold air to flow to lower elevations. The temperature extremes for Bidston Hill from 1920 to 1949 were recorded as 15 °F (−9 °C) and 87 °F (31 °C).[31]

Gallery

Bidston Windmill

Bidston Windmill Bidston Observatory

Bidston Observatory Bidston Lighthouse

Bidston Lighthouse View towards Liverpool

View towards Liverpool The former Joseph Proudman Building, demolished in 2013

The former Joseph Proudman Building, demolished in 2013 Carving of a horse's head

Carving of a horse's head Tam O-Shanter cottage

Tam O-Shanter cottage

References

- "Natural Areas and Greenspaces: Bidston Hill". Metropolitan Borough of Wirral. Archived from the original on 9 December 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- Kemble, Mike (15 July 2016). "The Wirral Hundred or The Wirral Peninsula". wirralhistory.net. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- Kemble, Mike (10 November 2015). "Bidston Village, Hall, Hill & Mill". wirralhistory.online. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- Brocklebank, Ralph T. (2003). Birkenhead: An Illustrated History. Breedon Books. p. 91. ISBN 1-85983-350-0.

- "Wirral Historic Settlement Study" (PDF). Museum of Liverpool. December 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- Irvine, William Ferguson (1893). Notes on the Ancient Parish of Bidston (PDF). The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire.

- Hough, E (2002). "Geology of the North Wirral district WA/98/66" (PDF). British Geological Survey. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- Bailey, Richard; Whalley, Jenny; Bowden, Alan; Tresise, Geoffrey (2006). "A miniature viking-age hogback from the Wirral" (PDF). The Antiquaries Journal. 86: 345–356. doi:10.1017/S0003581500000196. S2CID 162346133. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- "BGS Lexicon of Named Rock Units". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- Brownhill, John (1931). A history of the old parish of Bidston, Cheshire (PDF). The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire.

- Lysons, Daniel (1810). Magna Britannia. Cadell.

- Bidston Windmill Plaque (Engraving in stone). 53.397N -3.074W.

{{cite sign}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Butler, Heather; Davies, Felicity (2011). "Bidston Hill, Birkenhead, Wirral. An archaeological evaluation and assessment of the results" (PDF). Friends of Bidston Hill & Wirral and North Wales Field Archaeology. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- "Bidston Windmill official list entry". Historic England. 10 August 1992. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- "The Time Ball and the One O'clock Gun". Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- "Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory Annual Report, 2004-05 (page 26)" (PDF). Natural Environment Research Council. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- "The National Oceanography Centre, Liverpool". Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- Hughes, Lorna (23 August 2017). "Campaign over fears developer wants to build new houses on Bidston Hill". The Liverpool Echo.

- "Bidston Lighthouse". Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- "The French Visitor". Bidston Lighthouse. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Robinson, John; Robinson, Diane (2007). Lighthouses of Liverpool Bay. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752442099.

- "Has anyone seen our lamp?". Bidston Lighthouse. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Wardle, A.C (1948). "Liverpool merchant signals and house flags". Mariner's Mirror. 34 (3): 161. doi:10.1080/00253359.1948.10657523. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- Williams, Andrew (26 November 2021). "The Bidston Hill Signals Mug: A Who's Who of the Liverpool Slave Trade". Victoria Gallery and Museums, Liverpool University. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- "18 Lost in Foundered Bark". The New York Times. 24 August 1905. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- "The 'Bidston Hill' reduced to a barque rig [PRG 1373/6/89]". State Library South Australia. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- "Bidston Hill". Metropolitan Borough of Wirral. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- "Bidston Hill Underground Tunnels". wirralhistory.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 October 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- "Bidston Hill Management Plan 2022-2027" (PDF). Wirral Council Community Services Department Parks and Countryside Service. 15 January 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- "Report for the Year ending December 31, 1871". Report of the Meteorological Committee of the Royal Society. Royal Society (Great Britain). Meteorological Committee. 1868. p. 11.

- Smith, Wilfed; Monkhouse, F.J; Wilkinson, H.R, eds. (1953). Merseyside - A Scientific Survey. University Press of Liverpool, on behalf of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. p. 57.