Biesterfeldt Site

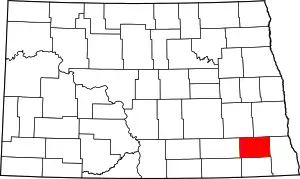

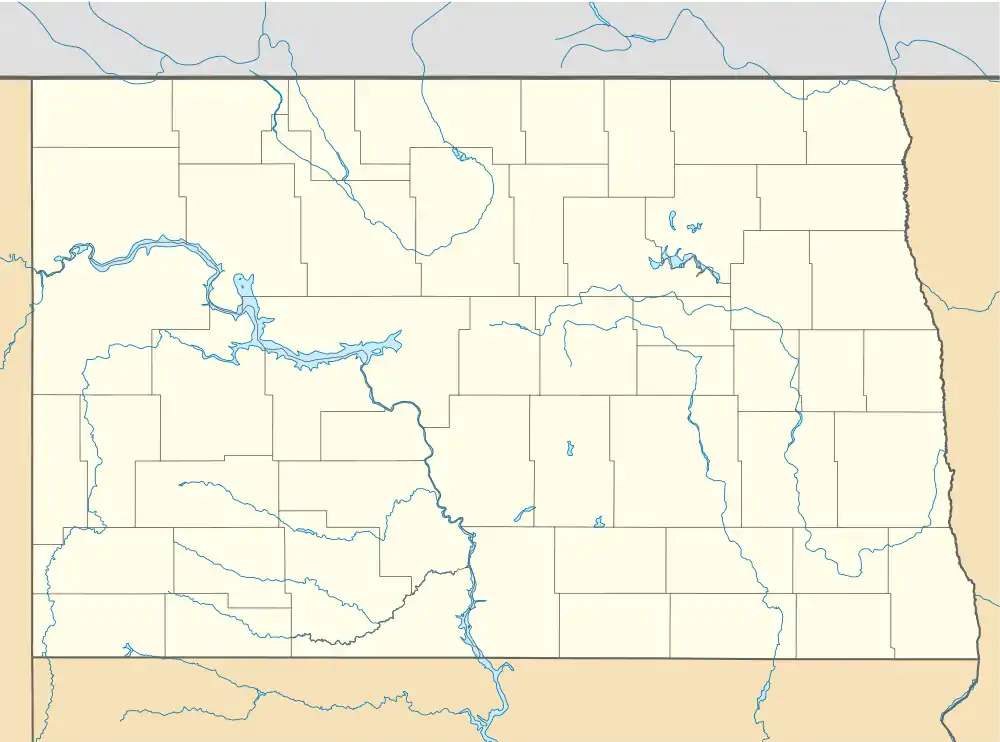

The Biesterfeldt Site (Shahienawoju in Lakota, and designated by the Smithsonian trinomial 32RM1) is an archaeological site near Lisbon, North Dakota, United States, located along the Sheyenne River. The site is the only documented village of earth lodges in the watershed of the Red River, and the only one that has been unambiguously affiliated with the Cheyenne tribe. An independent group of Cheyennes is believed to have occupied it c. 1724–1780. In 1980, the site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places because of its archaeological significance.[2] It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2016.[3]

Biesterfeldt Site (32RM1) | |

| |

| Location | Southern side of the Sheyenne River along 140th Ave.[1] |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Lisbon, North Dakota |

| Area | 4.5 acres (1.8 ha) |

| NRHP reference No. | 80002925[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | February 8, 1980 |

| Designated NHL | December 23, 2016 |

Description

The Biesterfeldt Site, in a wrong spelling named for its 1930s landowner Mr. Louis Biesterfeld,[4]: vii is located southeast of Lisbon, on a terrace overlooking a former channel of the Sheyenne River. The main area of the site is a rough oval bounded to the northwest by 30 feet (9.1 meters) step bank down to the former riverbed and on the other three sides by a fortification trench enclosing a total area of 4.5 acres (1.8 ha). The distance between the eastern and the western part of the trench is nearly 190 yards (170 meters).[4]: 9 The ditch was more than 10 feet (3.0 meters) wide and around 4 feet (1.2 meters) deep. It had sloping sides and a relatively wide and more or less flat bottom at the middle.[4]: 9 Something like postholes near the trench indicates the possibility that the village was shielded by a sort of palisade,[4]: 9 although clear evidence for one is missing.[5]: 14

The village consisted of around 70 circular earth lodges [4]: 9 of varying size with something like a plaza near its center.[4]: 11 It resembled the villages of the Arikara and Mandan at the Upper Missouri.[4]: v The diameter of the lodges ranged from roughly 18 to 45 feet (5.5 to 13.7 meters).[4]: 18 The entrance of all excavated houses pointed to the southeast, except for "House 16" with its opening to the southwest.[4]: 11 This spacious earth lodge faced the open center area in the village and could have been a ceremonial lodge.[4]: 11 The northern portion of the enclosure shows visible evidence of scattered lodge pits, while the area to the south, more intensively farmed in later historic times, has less visible signs of occupation.[5]

Bison scapula hoes,[4]: 48 two tools of fishbone,[4]: 39 shaft wrenches,[4]: 37 mauls,[4]: 35 pottery,[4]: 24–31 and other cultural artifacts, including a small amount of trade goods,[4]: 39–40 were unearthed in and near the lodges. Most of the artifacts differ little from those found in for instance Arikara villages.[4]: 50 Information gathered from historical accounts support a Cheyenne settlement.[4]: 50 It is known through archaeological test surveys that cultural artifacts extend outside the trench, but the extent of these has not been fully bounded.

Historical references

According to southern Cheyenne George Bent, the villagers planted corn. Having settled within the bison range, they became big game hunters. They hunted on foot in the beginning, since they had yet to acquire horses.[6]: 9 In winter, they would surround the buffalo, where the snow was deep, and then kill a whole herd.[6]: 10

The village's first mention in the historical record appears to be in 1794 in a journal kept by John Hay.[4]: 54–55 Explorer and fur trader David Thompson has retold how an unnamed Cheyenne village somewhere on Sheyenne River (now assumed Biesterfeldt) was wiped out and the lodges set ablaze in battle with the Ojibwe around 1790.[4]: 55–56 The Sibley expedition stopped near the locality in 1863 and both Stephen R. Riggs and A. L. Van Osdel inspected it.[4]: 57 United States Army Captain William H. Gardner described a visit to the site in 1868, including elements of its history from surrounding Native Americans, who claimed the Cheyenne were driven out by the Dakota. Assiniboines and Crees armed with fire weapons[6]: 12 are other enemies said to have caused the village dwellers to abandon Biesterfieldt[4]: 57 and start a new life near independent groups of Cheyennes already living west of the Missouri.[4]: 67 The westward migration "... was motivated by settling an area advantageous for trade purposes, rich in bison, and temporarily removed from military pressure ...".[4]: v

Archaeology

The first archaeologist to describe the site was the pioneering archaeologist Theodore H. Lewis, in 1890.[4]: 57 The first formal excavations took place in 1938, under the auspices of William Duncan Strong.[4]: vii–ix He and his team recovered a wide variety of artifacts, from glass beads to metal weapons (arrow points and a lance tip).[4]: 48 They found remains of bison, elk and other animals, including some horse bones.[4]: 49 Strong noted that many of the lodges showed evidence of destruction by fire in form of charred beams.[4]: 11

The site was used as farmland for most of the 20th century, primarily as pastureland after about 1950. The property was acquired by the Archaeological Conservancy in 2004 for permanent preservation. The site continues to be periodically investigated.[5]

See also

References

- Wood, W. Raymond (1955). "Pottery Types From The Biesterfeldt Site J North Dakota". Plains Anthropologist. 2 (3): 3–12. doi:10.1080/2052546.1955.11908171. JSTOR 25666201.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- National Park Service (March 3, 2017), Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 2/16/2017 through 3/2/2017, archived from the original on March 7, 2017, retrieved March 7, 2017

- Wood, W. Raymond (1971). "Biesterfeldt: A Post-Contact Coalescent Site on the Northeastern Plains". Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology. 15 (15): 1–109. doi:10.5479/si.00810223.15.1.

- "NHL nomination for Biesterfeldt Site (redacted)" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Hyde, George E. (1987): Life Of George Bent. Written From His Letters. Norman.