Biga (chariot)

The biga (Latin, plural bigae) is the two-horse chariot as used in ancient Rome for sport, transportation, and ceremonies. Other animals may replace horses in art and occasionally for actual ceremonies. The term biga is also used by modern scholars for the similar chariots of other Indo-European cultures, particularly the two-horse chariot of the ancient Greeks and Celts. The driver of a biga is a bigarius.[1]

Other Latin words that distinguish chariots by the number of animals yoked as a team are quadriga, a four-horse chariot used for racing and associated with the Roman triumph; triga, or three-horse chariot, probably driven for ceremonies more often than racing (see Trigarium); and seiugis or seiuga, the six-horse chariot, more rarely raced and requiring a high degree of skill from the driver. The biga and quadriga are the most common types.

Two-horse chariots are a common icon on Roman coins; see bigatus, a type of denarius so called because it depicted a biga.[2] In the iconography of religion and cosmology, the biga represents the moon, as the quadriga does the sun.[3]

Greek and Indo-European background

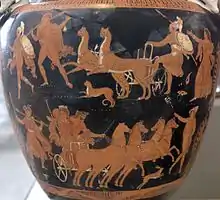

The earliest reference to a chariot race in Western literature is an event in the funeral games of Patroclus in the Iliad.[4] In Homeric warfare, elite warriors were transported to the battlefield in two-horse chariots, but fought on foot; the chariot was then used for pursuit or flight.[5] Most Bronze Age chariots uncovered by archaeology in Peloponnesian Greece are bigae.[6]

The date at which chariot races were introduced at the Olympian Games is recorded by later sources as 680 BC, when quadrigae competed. Races on horseback were added in 648. At Athens, two-horse chariot races were a part of athletic competitions from the 560s onward, but were still not a part of the Olympian Games.[7] Bigae drawn by mules competed in the 70th Olympiad (500 BC), but they were no longer part of the games after the 84th Olympiad (444 BC).[8] Not until 408 BC did bigae races begin to be featured at Olympia.[9]

In myth, the biga often functions structurally to create a complementary pair or to link opposites. The chariot of Achilles in the Iliad (16.152) was drawn by two immortal horses and a third who was mortal; at 23.295, a mare is yoked with a stallion. The team of Adrastos included the immortal "superhorse" Areion and the mortal Kairos.[10] A yoke of two horses is associated with the Indo-European concept of the Heavenly Twins, one of whom is mortal, represented among the Greeks by Castor and Pollux, the Dioscuri, who were known for horsemanship. [11]

Bigae at the races

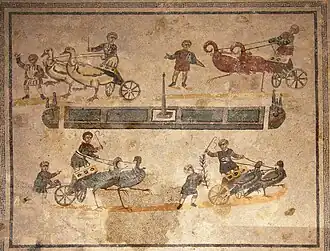

Horse- and chariot-races were part of the ludi, sacred games held during Roman religious festivals, from Archaic times. A magistrate who presented games was entitled to ride in a biga.[13] The sacral meaning of the races, though diminished over time,[14] was preserved by iconography in the Circus Maximus, Rome's main racetrack.

Inscriptions referring to the bigarius as young[15] suggest that a racing driver had to gain experience with a two-horse team before graduating to a quadriga.[16]

Construction

A main source for the construction of racing bigae is a number of bronze figurines found throughout the Roman Empire, a particularly detailed example of which is held by the British Museum. Other sources are reliefs and mosaics. These show a lightweight frame, to which a minimal shell of fabric or leather was lashed. The center of gravity was low, and the wheels were relatively small, around 65 cm in diameter in proportion to a body 60 cm wide and 55 cm deep, with a breastwork of about 70 cm in height. The wheels may have been rimmed with iron, but otherwise metal fittings are kept to a minimum. The design facilitated speed, maneuverability and stability.[17]

The weight of the vehicle has been estimated at 25–30 kg, with a maximum manned weight of 100 kg.[18] The biga is typically built with a single draught pole for a double yoke, while two poles are used for a quadriga.[19] The chariot for a two-horse racing team is not thought to differ otherwise from that drawn by a four-horse team, and so the horses of a biga pulled 50 kg each, while those of the quadriga pulled 25 kg each.[20]

The models or statuettes of bigae were art objects, toys, or collector's items. They are perhaps comparable to the modern hobby of model trains.[21]

Mythological and ceremonial use

In his Etymologiae, Isidore of Seville explains the cosmic symbolism of chariot racing, and notes that while the quadriga, or four-horse chariot, represents the sun and its course through the four seasons, the biga represents the moon, "because it travels on a twin course with the sun, or because it is visible both by day and by night – for they yoke together one black horse and one white."[22] Chariots frequently appear in Roman art as allegories of the Sun and Moon, particularly in reliefs and mosaics, in contexts that are readily distinguishable from depictions of real-world charioteers in the circus.[23]

Luna in her biga drawn by horses or oxen was an element of Mithraic iconography, usually in the context of the tauroctony. In the Mithraeum of S. Maria Capua Vetere, a wall painting that uniquely focuses on Luna alone shows one of the horses of the team as light in color, with the other a dark brown. It has been suggested that the duality of the horses drawing a biga can also represent Plato's metaphor of the charioteer who must control a soul divided by genesis and apogenesis.[24]

Greek and Roman art depicts deities driving two-yoke chariots drawn by a number of animals. A biga of oxen was driven by Hecate, the chthonic aspect of the Triple Goddess in complement with the "horned" or crescent-crowned Diana and Luna, to whom the biga was sacred.[25] Triptolemus is depicted on Roman coins as driving a serpent-drawn biga as he sows grain in response to Demeter's appeal to him to teach mankind the skill of agriculture, such as on an Alexandrine drachma.

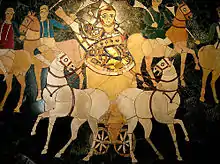

Leopard-drawn biga in a scene from the Mysteries (Apulian red-figure volute-krater, c. 340 BC)

Leopard-drawn biga in a scene from the Mysteries (Apulian red-figure volute-krater, c. 340 BC) Pair of tigers drawing the chariot of Dionysus (mosaic, Roman Spain)

Pair of tigers drawing the chariot of Dionysus (mosaic, Roman Spain) Ox-drawn biga of Luna or Diana (Parabiago patera, 4th century)

Ox-drawn biga of Luna or Diana (Parabiago patera, 4th century)

In his chapter on gemstones, Pliny records a ritualized use of the biga, saying those who seek the draconitis or draconitias, "snake stone", ride in a biga.[26]

Bigatus

The bigatus was a silver coin so called because it depicted a biga. Luna in her two-horse chariot was depicted on the first issue of the bigatus. Victory in her biga was later featured.[27]

References

- CIL 6.10078 and 6.37836. The general term for chariot driver is auriga.

- This is disputed.

- Doro Levi, "Aion," Hesperia 13.4 (1944), p. 287.

- John H. Humphrey, Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing (University of California Press, 1986), p. 5.

- Donald G. Kyle, Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World (Blackwell, 2007), pp. 161–162.

- Mary Aiken Littauer, "The Military Use of the Chariot in the Aegean in the Late Bronze Age," in Selected Writings on Chariots, Other Early Vehicles, Riding and Harness (Brill, 2002), p. 90.

- Kyle, Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World, p. 161.

- Edward M. Plummer, Athletics and Games of the Ancient Greeks (Cambridge, Mass., 1898), p. 38.

- Humphrey, Roman Circuses, pp. 6–7.

- Antimachus apud Pausanias 8.25.9. A psychoanalytic discussion of this yoking is given by George Devereux, Dreams in Greek Tragedy: An Ethno-Psycho-Analytical Study (University of California Press, 1976), p. 12

- Robert Drews, The Coming of the Greeks: Indo-European Conquests in the Aegean and the Near East (Princeton University Press, 1988), p. 152.

- As identified by Katherine M.D. Dunbabin, "The Victorious Charioteer on Mosaics and Related Monuments," American Journal of Archaeology 86.1 (1982), p. 71.

- Frank Bernstein, "Complex Rituals: Games and Processions in Republican Rome," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 224. For an example as recorded in an inscription, see CIL 10.7295 = ILS 5055.

- Mary Beard, J.A. North, and S.R.F. Price, Religions of Rome: A History (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 262. The Church Fathers recognized the religious significance of ludi, including both sporting events and theater, and therefore instructed Christians not to participate; see, for instance, Tertullian, De spectaculis.

- Puerilis in CIL 6.100078 = ILS 9348; infans in ILS 5300.

- Jean-Paul Thuillier, "Le cirrus et la barbe. Questions d'iconographie athlétique romaine," Mélanges de l'École française de Rome, Antiquité 110.1 (1998), p. 377, noting that the "major and minor" races held for the Robigalia may be junior and senior divisions.

- Marcus Junkelmann, "On the Starting Line with Ben Hur: Chariot-Racing in the Circus Maximus," in Gladiators and Caesars (University of California Press, 2000), pp. 91–92.

- Junkelmann, "On the Starting Line with Ben Hur," pp. 91–92.

- J.H. Crouwell, "Chariots in Iron Age Cyprus," in Selected Writings on Chariots, Other Early Vehicles, Riding and Harness (Brill, 2002), p. 153ff.

- Junkelmann, "On the Starting Line with Ben Hur,", pp. 91–92.

- The Roman historian Suetonius records that "At the beginning of his reign [Nero] used to play every day with ivory chariots on a board" (Sed cum inter initia imperii eburneis quadrigis cotidie in abaco luderet). Play in abaco ("on a gameboard") may imply a strategic game with rules; for other Roman board games see ludus duodecim scriptorum and ludus latrunculorum. The ivory quadrigae may have been actual miniatures, or game pieces that represented the chariots. See Junkelmann, "On the Starting Line," p. 89.

- Isidore, Etymologies 18.26, as translated by Stephen A. Barney et al., The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville (Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 368 online.

- Dunbabin, "The Victorious Charioteer on Mosaics and Related Monuments," p. 85.

- M.J. Vermaseren, Mithraica I: The Mithraeum at S. Maria Capua Vetere (Brill, 1971), pp–15. 14; Plato, Phaedrus 246.

- Prudentius, Contra Symmachum 733 (Migne); Friedrich Solmsen, "The Powers of Darkness in Prudentius' Contra Symmachum: A Study of His Poetic Imagination," Vigiliae Christianae 19.4 (1965), p. 248. See Servius, note to Aeneid 6.118 on the identification of Hecate trimorphos with Luna, Diana, and Proserpina. According to Hesiod, Theogony 413f., Hecate originally had power over the heavens, land, and sea, not heaven, earth, and underworld.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 37.158 (Loeb numbering 57).

- Michael H. Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage (Cambridge University Press, 1974), pp. 720–721.