Memnon

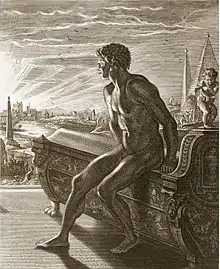

In Greek mythology, Memnon (/ˈmɛmnən/; Ancient Greek: Μέμνων means 'resolute'[1]) was a king of Aethiopia and son of Tithonus and Eos. As a warrior he was considered to be almost Achilles' equal in skill. During the Trojan War, he brought an army to Troy's defense and killed Antilochus, Nestor's son, during a fierce battle. Nestor challenged Memnon to a fight, but Memnon refused, being there was little honor in killing the aged man. Nestor then pleaded with Achilles to avenge his son's death. Despite warnings that soon after Memnon fell so too would Achilles, the two men fought. Memnon drew blood from Achilles, but Achilles drove his spear through Memnon's chest, sending the Aethiopian army running. The death of Memnon echoes that of Hector, another defender of Troy whom Achilles also killed out of revenge for a fallen comrade, Patroclus.

After Memnon's death, Zeus was moved by Eos' tears and granted him immortality. Memnon's death is related at length in the lost epic Aethiopis, composed after The Iliad, circa the 7th century BC. Quintus of Smyrna records Memnon's death in Posthomerica. His death is also described in Philostratus' Imagines.

Dictys Cretensis, author of a pseudo-chronicle of the Trojan War, writes that "Memnon, the son of Tithonus and Aurora, arrived with a large army of Indians and Aethiopians, a truly remarkable army which consisted of thousands and thousands of men with various kinds of arms, and surpassed the hopes and prayers even of Priam."[2]

Mythology

Memnon in Quintus of Smyrna's Posthomerica

Memnon leading his army of Aethiopians, arrives at Troy in the immediate aftermath of an argument between Polydamas, Helen, and Priam that centres on whether or not the Aethiopian King will show up at all. Memnon's army is described as being too big to be counted and his arrival starts a huge banquet in his honour. As per usual the two leaders (Memnon and, in this case, Priam) end the dinner by exchanging glorious war stories, and Memnon's tales lead Priam to declare that the Aethiopian King will be Troy's saviour. Despite this, Memnon is very humble and warns that his strength will, he hopes, be seen in battle, although he believes it is unwise to boast at dinner.

Before the next day's battle, so great is the divine love towards Memnon that Zeus makes all the other Olympians promise not to interfere in the fighting. In battle, Memnon kills Nestor's son, Antilochos, after Antilochos has killed Memnon's dear comrade, Aesop. Seeking vengeance and despite his age, Nestor tries to fight Memnon but the Aethiopian warrior insists it would not be just to fight such an old man, and respects Nestor so much that he refuses to fight. In this way, Memnon is seen as very similar to Achilles – both of them have strong sets of values that are looked upon favourably by the warrior culture of the time.

When Memnon reaches the Greek ships, Nestor begs Achilles to fight him and avenge Antilochos, leading to the two men clashing while both wearing divine armour made by Hephaestus, making another parallel between the two warriors. Zeus favours both of them and makes each man tireless and huge so that the whole battlefield can watch them clash as demigods. Eventually, Achilles stabs Memnon through the heart, causing his entire army to flee in terror.

In honour of Memnon, the gods collect all the drops of blood that fall from him and use them to form a huge river that on every anniversary of his death will bear the stench of human flesh.[3] The Aethiopians that stayed close to Memnon in order to bury their leader are turned into birds (which we now call Memnonides)[4] and they stay by his tomb so as to remove dust that gathers on it.[5]

Memnon in Africa

Roman writers and later classical Greek writers such as Diodorus Siculus believed Memnon hailed from "Aethiopia", a geographical area in Africa, usually south of Egypt. Because the original historical work by Arctinus of Miletus only survives in fragments, most of what is known about Memnon comes from post-Homeric Greek and Roman writers. Homer only makes passing mention to Memnon in the Odyssey.[6]

Herodotus called Susa "the city of Memnon,"[7] Herodotus describes two tall statues with Egyptian and Aethiopian dress that some, he says, identify as Memnon; he disagrees, having previously stated that he believes it to be Sesostris.[8] One of the statues was on the road from Smyrna to Sardis.[9] Herodotus described a carved figure matching this description near the old road from Smyrna to Sardis.[10]

Pausanias describes how he marveled at a colossal statue in Egypt, having been told that Memnon began his travels in Africa:

In Egyptian Thebes, on crossing the Nile to the so-called Pipes, I saw a statue, still sitting, which gave out a sound. The many call it Memnon, who they say from Aethiopia overran Egypt and as far as Susa. The Thebans, however, say that it is a statue, not of Memnon, but of a native named Phamenoph, and I have heard some say that it is Sesostris. This statue was broken in two by Cambyses, and at the present day from head to middle it is thrown down; but the rest is seated, and every day at the rising of the sun it makes a noise, and the sound one could best liken to that of a harp or lyre when a string has been broken.[11]

Philostratus of Lemnos in his work Imagines, describes artwork of a scene which depicts Memnon:

Now such is the scene in Homer, but the events depicted by the painter are as follows: Memnon coming from Aethiopia slays Antilochus, who has thrown himself in front of this father, and he seems to strike terror among the Achaeans – for before Memnon's time black men were but a subject for story – and the Achaeans, gaining possession of the body, lament Antilochus, both the sons of Atreus and the Ithacan and the son of Tydeus and the two heroes of the same name.[12]

According to Manetho Memnon and the 8th Pharaoh of the 18th dynasty Amenophis was one and the same king.[13]

Memnon son of Eos (Dawn) and Tithonus

According to ancient Greek poets, Memnon's father Tithonus was snatched away from Troy by the goddess of dawn Eos and was taken to the ends of the earth on the coast of Oceanus.[14]

According to Hesiod Eos bore to Tithonus bronzed armed Memnon, the King of the Aethiopians and lordly Emathion.[15] Zephyrus, god of the west wind, like Memnon was also the first-born son of Eos by another father Astraeus, making him the half-brother of Memnon. According to Quintus Smyrnaeus, Memnon said himself that he was raised by the Hesperides on the coast of Oceanus.[16] Memnon dwelling on the western Ocean and his father being driven there would make him the son of dawn (the east) as in the son of Troy rather than the son of eastern Asia as earlier scholars have proposed based on their opinion.

When Memnon died, Eos mourned greatly over the death of her son, and made the light of her brother, Helios (Sun), to fade, and begged Nyx (Night), to come out earlier, so she could be able to freely steal her son's body undetected by the armies of the Greeks and the Trojans.[17] After his death, Eos, perhaps with the help of Hypnos and Thanatos, the gods of sleep and death respectively, transported the slain Memnon's dead body back to Aethiopia,[18] and also asked Zeus to make Memnon immortal, a wish he granted.[19]

There are statues of Amenhotep III in the Theban Necropolis in Egypt that were known to the Romans as the Colossi of Memnon. According to Pliny the Elder and others, one statue made a sound at morning time.[20]

Notes

- Graves, Robert (2017). The Greek Myths – The Complete and Definitive Edition. Penguin Books Limited. p. 682. ISBN 978-0-241-98338-6.

- "digilibLT – Ephemeris belli Troiani". digiliblt.lett.unipmn.it. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- Quintus & James 2004, pp. 39, 556–60

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Memnon. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - Quintus & James 2004

- Homer, Odyssey 11.522

- Herodotus, 5.54 & 7.151

- "Also, there are in Ionia two figures of this man carved in rock, one on the road from Ephesus to Phocaea, and the other on that from Sardis to Smyrna. In both places, the figure is over twenty feet high, with a spear in his right hand and a bow in his left, and the rest of his equipment proportional; for it is both Egyptian and Aethiopian; and right across the breast from one shoulder to the other a text is cut in the Egyptian sacred characters, saying: 'I myself won this land with the strength of my shoulders.' There is nothing here to show who he is and whence he comes, but it is shown elsewhere. Some of those who have seen these figures guess they are Memnon, but they are far indeed from the truth."

- Herodotus 2003, p. 135

- Herodotus 2003, p. 640

- Pausanias (1918). Description of Greece. Translated by W. H. S. Jones. Harvard University Press; William Heinmann Ltd. ISBN 978-0-674-99104-0.

- "PHILOSTRATUS THE ELDER, IMAGINES BOOK 2.1-16 – Theoi Classical Texts Library". www.theoi.com.

- Manetho, Aegyptica 2

- Homeric Hym to Aphrodite 215

- Hesiod, Theogony 984

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, 2

- "ToposText". topostext.org. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- Currie, Bruno (2010-04-29). Pindar and the Cult of Heroes. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-161516-0.

- "Proclus, Proclus' Summary of the Aithiopis, attributed to Arctinus of Miletus". 2011-06-07. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 36.11

References

- Dictys Cretensis, from The Trojan War. The Chronicles of Dictys of Crete and Dares the Phrygian translated by Richard McIlwaine Frazer, Jr. (1931-). Indiana University Press. 1966. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths, Harmondsworth, London, England, Penguin Books, 1960. ISBN 978-0143106715

- Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths: The Complete and Definitive Edition. Penguin Books Limited. 2017. ISBN 978-0-241-98338-6, 024198338X

- Herodotus (2003). The Histories. London, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- Herodotus, The Histories with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920. ISBN 0-674-99133-8. Online version at the Topos Text Project. Greek text available at Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. ISBN 978-0674995611. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

- Philostratus the Elder. Imagines, translated by Arthur Fairbanks (1864–1944). Loeb Classical Library Volume 256. London: William Heinemann, 1931. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Philostratus the Lemnian (Philostratus Major), Flavii Philostrati Opera. Vol 2. Carl Ludwig Kayser. in aedibus B. G. Teubneri. Lipsiae. 1871. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pliny the Elder, The Natural History. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia. Karl Friedrich Theodor Mayhoff. Lipsiae. Teubner. 1906. Latin text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Quintus; James, Alan W. (2004). The Trojan Epic: Posthomerica. Vol. Book II. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, The Fall of Troy translated by Way. A. S. Loeb Classical Library Volume 19. London: William Heinemann, 1913. Online version at theoi.com

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, The Fall of Troy. Arthur S. Way. London: William Heinemann; New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1913. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

Further reading

- Griffith, R. Drew. "The Origin of Memnon." Classical Antiquity 17, no. 2 (1998): 212-34. Accessed June 15, 2020. doi:10.2307/25011083.

- Heichelheim, F. M. "THE HISTORICAL DATE FOR THE FINAL MEMNON MYTH." Rheinisches Museum Für Philologie 100, no. 3 (1957): 259-63. Accessed June 15, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41243876.

- Petit, Thierry. "Amathousiens, Éthiopiens et Perses". In: Cahiers du Centre d'Etudes Chypriotes. Volume 28, 1998. pp. 73–86. [DOI: Amathousiens, Éthiopiens et Perses; www.persee.fr/doc/cchyp_0761-8271_1998_num_28_1_1340

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)