Iris (mythology)

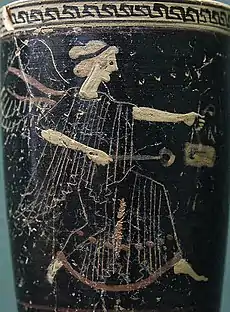

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Iris (/ˈaɪrɪs/; EYE-riss; Greek: Ἶρις, translit. Îris, lit. "rainbow,"[2][3] Ancient Greek: [îːris]) is a daughter of the gods Thaumas and Electra,[4] the personification of the rainbow and messenger of the gods, a servant to the Olympians and especially Queen Hera.[5] Iris appears in several stories carrying messages from and to the gods or running errands but has no unique mythology of her own. Similarly, very little to none of a historical cult and worship of Iris is attested in surviving records, with only a few traces surviving from the island of Delos. In ancient art, Iris is depicted as a winged young woman carrying a caduceus, the symbol of the messengers, and a pitcher of water for the gods. Iris was traditionally seen as the consort of Zephyrus, the god of the west wind and one of the four Anemoi, by whom she is the mother of Pothos in some versions.[1]

| Iris | |

|---|---|

Goddess of the Rainbow | |

Gaetano Matteo Monti, Iris as goddess of the rainbow (1841, marble) at Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Austria. | |

| Abode | Mount Olympus (possibly) |

| Symbol | Rainbow, caduceus, pitcher (container) |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Thaumas and Electra |

| Siblings | Arke, Harpies, Hydaspes |

| Consort | Zephyrus |

| Offspring | Pothos[1] |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

Etymology

The ancient Greek noun Ἶρις means both the rainbow[2] and the halo of the Moon.[6] An inscription from Corinth provides evidence for an original form Ϝῖρις (wîris) with a digamma that was eventually dropped.[6] The noun seems to be of pre-Greek origin.[7] A Proto-Indo-European pre-form *uh2i-r-i- has been suggested, although Beekes finds it 'hard to motivate.'[6]

Family

According to Hesiod's Theogony, Iris is the daughter of Thaumas and the Oceanid Electra and the sister of the Harpies: Arke and Ocypete.[8] During the Titanomachy, Iris was the messenger of the Olympian gods while her sister Arke betrayed the Olympians and became the messenger of the gods' enemy, the Titans. She is the goddess of the rainbow. She also serves nectar to the goddesses and gods to drink. Zephyrus, who is the god of the west wind, is her consort. Together they had a son named Pothos,[9] or alternatively they were the parents of Eros,[10] the god of love, according to sixth century BC Greek lyric poet Alcaeus, though Eros is usually said to be the son of Ares and Aphrodite. According to the Dionysiaca of Nonnus, Iris' brother is Hydaspes.[11]

She is also known as one of the goddesses of the sea and the sky. Iris links the gods to humanity. She travels with the speed of wind from one end of the world to the other[12] and into the depths of the sea and the underworld.

Mythology

Titanomachy

Iris is said to travel on the rainbow while carrying messages from the gods to mortals. In some records, Iris is a sister to fellow messenger goddess Arke ("swift", "quick"), who flew out of the company of Olympian gods to join the Titans as their messenger goddess during the Titanomachy, making the two sisters enemy messenger goddesses. After the war was won by Zeus and his allies, Zeus tore Arke's wings from her and in time gave them as a gift to the Nereid Thetis at her wedding to Peleus, who in turn gave them to her son, Achilles, who wore them on his feet.[13] Achilles was sometimes known as podarkes (feet like [the wings of] Arke). Podarces was also the original name of Priam, the king of Troy.[14]

Messenger of the gods

Following her daughter Persephone's abduction by Hades, the goddess of agriculture Demeter withdrew to her temple in Eleusis and made the earth barren, causing a great famine that killed off mortals, and as a result sacrifices to the gods ceased. Zeus then sent Iris to Demeter, calling her to join the other gods and lift her curse; but as her daughter was not returned, Demeter was not persuaded.[15]

In one narrative, after Leto and her children pleaded with Zeus to release Prometheus from his torment, Zeus relented, and sent Iris to order Heracles to free the unfortunate Prometheus.[16]

After Ceyx drowned in a shipwreck, Hera made Iris convey her orders to Hypnos, the god of sleep. Iris flew and found him in his cave, and informed him that Hera wished for Ceyx's wife, Alcyone, to be informed of her loved one's death in her dreams. After delivering Hera's command, Iris left immediately, not standing to be near Hypnos for too long, for his powers took hold of her, and made her dizzy and sleepy.[17]

In Aristophanes's comedy The Birds, the titular birds build a city in the sky and plan to supplant the Olympian gods. Iris, as the messenger, goes to meet them, but she is ridiculed, insulted, and threatened with rape by their leader Pisetaerus, an elderly Athenian man. Iris appears confused that Pisetearus does not know who the gods are and that she is one of them. Pisetaerus then tells her that the birds are the gods now, the deities whom the humans must sacrifice to. After Pisetaerus threatens to rape her, Iris scolds him for his foul language and leaves, warning him that Zeus, whom she refers to as her father, will deal with him and make him pay.[18]

Iris also appears several times in Virgil's Aeneid, usually as an agent of Juno. In Book 4, Juno dispatches her to pluck a lock of hair from the head of Queen Dido, so that she may die and enter Hades.[19] In book 5, Iris, having taken on the form of a Trojan woman, stirs up the other Trojan mothers to set fire to four of Aeneas' ships in order to prevent them from leaving Sicily.[20]

According to the Roman poet Ovid, after Romulus was deified as the god Quirinus, his wife Hersilia pleaded with the gods to let her become immortal as well so that she could be with her husband once again. Juno heard her plea and sent Iris down to her. With a single finger, Iris touched Hersilia and transformed her into an immortal goddess. Hersilia flew to Olympus, where she became one of the Horae and was permitted to live with her husband forevermore.[21][22]

Trojan War

According to the lost epic Cypria by Stasinus, it was Iris who informed Menelaus, who had sailed off to Crete, of what had happened back in Sparta while he was gone, namely his wife Helen's elopement with the Trojan Prince Paris as well as the death of Helen's brother Castor.[23]

Iris is frequently mentioned as a divine messenger in The Iliad, which is attributed to Homer. She does not, however, appear in The Odyssey, where her role is instead filled by Hermes. Like Hermes, Iris carries a caduceus or winged staff. By command of Zeus, the king of the gods, she carries a ewer of water from the River Styx, with which she puts to sleep all who perjure themselves. In Book XXIII, she delivers Achilles's prayer to Boreas and Zephyrus to light the funeral pyre of Patroclus.[24] In the last book, Zeus sends Iris to King Priam, to tell him that he should go to the Achaean camp alone and ransom the body of his slain son Hector from Achilles. Iris swiftly delivers the message to Priam and returns to Olympus.[25]

Other myths

According to the "Homeric Hymn to Apollo", when Leto was in labor prior to giving birth to her twin children Apollo and Artemis, all the goddesses were in attendance except for two, Hera and Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth. On the ninth day of her labor, Leto told Iris to bribe Eileithyia and ask for her help in giving birth to her children, without allowing Hera to find out.[26] According to Callimachus, Iris along with Ares ordered, on Hera's orders, all cities and other places to shun the pregnant Leto and deny her shelter where she could bring forth her twins.[27] After Asteria, now transformed into the island of Delos, offered shelter to Leto, Iris flew back to Hera to inform her that Leto had been allowed to give birth due to Asteria defying Hera's orders, and took her seat beside Hera.[28]

According to Apollonius Rhodius, Iris turned back the Argonauts Zetes and Calais, who had pursued the Harpies to the Strophades ("Islands of Turning"). The brothers had driven off the monsters from their torment of the prophet Phineus, but did not kill them upon the request of Iris, who promised that Phineus would not be bothered by the Harpies again.

After King Creon of Thebes forbade the burial of the dead Argive soldiers who had raised their arms against Thebes, Hera ordered Iris to moisturize their dead bodies with dew and ambrosia.[29]

In a lesser-known narrative, Iris once came close to being raped by the satyrs after she attempted to disrupt their worship of Dionysus, perhaps at the behest of Hera. About fifteen black-and-red-figure vase paintings dating from the fifth century BC depict said satyrs either menacingly advancing toward or getting hold of her when she tries to interfere with the sacrifice.[30] In another cup, Iris is depicted being assaulted by the satyrs, who apparently are trying to prevent Iris from stealing sacrificial meat from the altar of Dionysus, who is also present in the scene. On the other side, the satyrs are attacking Hera, who stands between Hermes and Heracles.[31] The ancient playwright Achaeus wrote Iris, a now lost satyr play, which might have been the source of those vases' subject.[31]

In Euripides' play Heracles Gone Mad, Iris appears alongside Lyssa, the goddess of madness and insanity, cursing Heracles with the fit of madness in which he kills his three sons and his wife Megara.[32] Iris also prepared the bed of Zeus and Hera.[33]

Worship

Cult

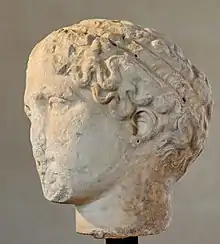

Unlike the other prominent messenger god of the Greeks, Hermes, Iris did not play a large part in the ancient Greek religion and was rarely worshipped. There are no known temples, shrines, or sanctuaries to Iris, or festivals held in her honour. While she is frequently depicted on vases and in bas-reliefs, few statues are known to have been made of Iris during antiquity. She was however depicted in sculpture on the west pediment of Parthenon in Athens.

Iris does appear to have been the object of at least some minor worship, but the only trace preserved of her cult is the note by Athenaeus in Scholars at Dinner that the people of Delos sacrificed to Iris, offering her cheesecakes called basyniae, a type of cake of wheat-flour, suet, and honey, boiled up together.[35]

Epithets

Iris had numerous poetic titles and epithets, including chrysopteros (χρυσόπτερος "golden winged"), podas ōkea (πόδας ὠκέα "swift footed") or podēnemos ōkea (ποδήνεμος ὠκέα "wind-swift footed"), roscida ("dewy", Latin), and Thaumantias or Thaumantis (Θαυμαντιάς, Θαυμαντίς, "Daughter of Thaumas, Wondrous One"), aellopus (ἀελλόπους "storm-footed, storm-swift).[36] She also watered the clouds with her pitcher, obtaining the water from the sea.

Representation

Iris is represented either as a rainbow or as a beautiful young maiden with wings on her shoulders. As a goddess, Iris is associated with communication, messages, the rainbow, and new endeavors. This personification of a rainbow was once described as being a link to the heavens and earth.[37]

In some texts she is depicted wearing a coat of many colors. With this coat she actually creates the rainbows she rides to get from place to place. Iris' wings were said to be so beautiful that she could even light up a dark cavern, a trait observable from the story of her visit to Somnus in order to relay a message to Alcyone.[38]

While Iris was principally associated with communication and messages, she was also believed to aid in the fulfillment of humans' prayers, either by fulfilling them herself or by bringing them to the attention of other deities.[39]

In the sciences

Gallery

- Iris in art

_Flaxman_Ilias_1795%252C_Zeichnung_1793%252C_183_x_244_mm_mm.jpg.webp) Iris sent by Jove in the Iliad (engraving by Tommaso Piroli after John Flaxman)

Iris sent by Jove in the Iliad (engraving by Tommaso Piroli after John Flaxman) The Iris: an Illuminated Souvenir (1852)

The Iris: an Illuminated Souvenir (1852) Alegoría del Aire by Antonio Palomino (circa 1700)

Alegoría del Aire by Antonio Palomino (circa 1700) Juno, Iris and Flora by François Lemoyne

Juno, Iris and Flora by François Lemoyne Grèce - Série courante de 1913-24 Type "Iris" - litho - Yvert 198B

Grèce - Série courante de 1913-24 Type "Iris" - litho - Yvert 198B Iris (tiré d'un vase antique). Illustration de "Histoires des météores" (1870)

Iris (tiré d'un vase antique). Illustration de "Histoires des météores" (1870) Morpheus awakening as Iris draws near by René-Antoine Houasse (1690)

Morpheus awakening as Iris draws near by René-Antoine Houasse (1690) Iris and Jupiter by Michel Corneille the Younger (1701)

Iris and Jupiter by Michel Corneille the Younger (1701) Iris depicted by John Atkinson Grimshaw

Iris depicted by John Atkinson Grimshaw.jpg.webp) Iris from the East Pediment of the Parthenon

Iris from the East Pediment of the Parthenon

See also

- Rainbow deity

- Angelia, another messenger goddess.

- Angel

- Ithax, the Titans's messenger god.

- Ninshubur

Notes

- Nonnus. Dionysiaca. 47.340.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "ἶρις". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- Etymology of ἶρις in Bailly, Anatole (1935) Le Grand Bailly: Dictionnaire grec-français, Paris: Hachette.

- In some rarer traditions, she is the daughter of Zeus.

- Smith, s.v. Iris.

- Beekes 2009, p. 1:598.

- Fur.: 356.

- Hesiod, Theogony 265; cf. Apollodorus, 1.2.6.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 47.340

- Alcaeus frag 149

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 26.355–365

- The Iliad, Book II, "And now Iris, fleet as the wind, was sent by Jove to tell the bad news among the Trojans."

- Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History Book 6; epitomized in Photius' Bibliotheca 190

- Andrews, P. B. S. (1965). "The Falls of Troy in Greek Tradition". Greece & Rome. 12 (1): 28–37. doi:10.1017/S0017383500014753. ISSN 0017-3835. JSTOR 642402. S2CID 162661766. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- Homeric Hymns 2.314–325

- Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 4.60-78 ff

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.585

- Welsh 2014, p. 29.

- Virgil, Aeneid 4.696

- Virgil, Aeneid 5.606

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 14.829–851

- McLeish, Kenneth. "Bloomsbury Dictionary of Myth". Credo Reference.

- Proclus' summary of Stasinus' Cypria.

- Mackie, Christopher John (2011). "The Homer Encyclopedia". Credo Reference.

- Homer, Iliad 24.144–189

- Grant, Michael (2002). "Who's Who in Classical Mythology, Routledge". Credo Reference.

- Callimachus, Hymn to Delos 67–69

- Callimachus, Hymn to Delos 110–228

- Statius, Thebaid 12.138 ff

- Sells 2019, p. 112.

- Antonopoulos, Christopoulos & Harrison 2021, pp. 627–628.

- Euripides, Heracles 822

- Theocritus, Idylls 15.135

- British museum Marble statue from the West pediment of the Parthenon.

- Athenaeus, Scholars at Dinner 14.53; comp. Müller, Aegin. p. 170.

- Homer uses the alternative form aellopos (ἀελλόπος): Iliad viii. 409.

- Seton-Williams, M.V. (2000). Greek Legends and Stories. Rubicon Press. pp. 75–76.

- Bulfinch, Thomas (1913). Bulfinch's Mythology: the Age of Fable, the Age of Chivalry, Legends of Charlemagne: Complete in One Volume. Thomas Y. Crowell Co.

- Seton-Williams, M.V. (2000). Greek Legends and Stories. Rubicon Press. p. 9.

Bibliography

Ancient sources

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica translated by Robert Cooper Seaton (1853–1915), R. C. Loeb Classical Library Volume 001. London, William Heinemann Ltd, 1912. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Callimachus. Hymns, translated by Alexander William Mair (1875–1928). London: William Heinemann; New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1921. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PhD in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Evelyn-White, Hugh, The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

- Euripides, The Complete Greek Drama', edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. in two volumes. 2. The Phoenissae, translated by E. P. Coleridge. New York. Random House. 1938.

- Ovid. Metamorphoses, Volume I: Books 1–8. Translated by Frank Justus Miller. Revised by G. P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library No. 42. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1977, first published 1916. ISBN 978-0-674-99046-3. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Statius, Thebaid, Volume II: Thebaid: Books 8–12. Achilleid. Edited and translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Loeb Classical Library 498. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Theocritus, Idylls and Epigrams with an Epilogue, translation by Daryl Hine, New York, Atheneum, 1982, ISBN 0-689-11320-X.

- Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica. Translated by J. H. Mozley. Loeb Classical Library 286. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1934.

- Vergil, Aeneid. Theodore C. Williams. trans. Boston. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1910. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

Modern sources

- Antonopoulos, Andreas P.; Christopoulos, Menelaos M.; Harrison, George W. M. (July 5, 2021). Reconstructing Satyr Drama. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110725216.

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Leiden: Brill Publications. p. 1:598.

- Grimal, Pierre (1996). "Iris". The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. ISBN 978-0-631-20102-1. pp. 237–238.

- Peyré, Yves (2009). "Iris". A Dictionary of Shakespeare's Classical Mythology, ed. Yves Peyré.

- Sells, Donald (2019). Parody, Politics and the Populace in Greek Old Comedy. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-3500-6051-7.

- Welsh, Alexander (2014). The Humanist Comedy. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19751-8.

- Smith, William (1873). "Iris". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. London.

External links

- IRIS from The Theoi Project

- IRIS from Greek Mythology Link

- IRIS from greekmythology.com

- Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns, and Homerica by Hesiod (English translation at Project Gutenberg)

- The Iliad by Homer (English translation at Project Gutenberg)

- The Argonautica, by c. 3rd century BC Apollonius Rhodius (English translation at Project Gutenberg)

- The Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (images of Iris)