Xenophanes

Xenophanes of Colophon (/zəˈnɒfəniːz/ zə-NOF-ə-neez;[1][2] Ancient Greek: Ξενοφάνης ὁ Κολοφώνιος [ksenopʰánɛːs ho kolopʰɔ̌ːnios]; c. 570 – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and critic of Homer from Ionia who travelled throughout the Greek-speaking world in early Classical Antiquity.

Xenophanes | |

|---|---|

Fictionalized portrait of Xenophanes from a 17th-century engraving | |

| Born | c. 570 BC |

| Died | c. 478 BC (aged c. 92) |

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

Main interests | Social criticism Kataphasis Natural philosophy Epistemology |

Notable ideas | Religious polytheistic views as human projections Earth and water is the arche The distinction between knowledge and mere true belief. |

As a poet, Xenophanes was known for his critical style, writing poems that are considered among the first satires. He also composed elegiac couplets that criticised his society's traditional values of wealth, excesses, and athletic victories. He also criticised Homer and the other poets in his works for representing the gods as foolish or morally weak. His poems have not survived intact; only fragments of some of his work survives in quotations by later philosophers and literary critics.

Xenophanes is seen as one of the most important pre-Socratic philosophers. A highly original thinker, Xenophanes sought explanations for physical phenomena such as clouds or rainbows without references to divine or mythological explanations, but instead based on first principles. He also distinguished between different forms of knowledge and belief, an early instance of epistemology. Later philosophers such as the Eleatics and the Pyrrhonists also saw Xenophanes as the founder of their doctrines, and interpreted his work in terms of those doctrines, although modern scholarship disputes these claims.

Life

The Ancient biographer Diogenes Laertius reports that Xenophanes was born in Colophon, a city that once existed in Ionia, in present day Turkey.[3][lower-alpha 1] Laertius says that Xenophanes is said to have flourished during the 60th Olympiad (540–537 BC),[lower-alpha 2] and modern scholars generally place his birth some time around 570-560 BC.[3] His surviving work refers to Thales, Epimenides, and Pythagoras,[lower-alpha 3] and he himself is mentioned in the writings of Heraclitus and Epicharmus.[lower-alpha 4]

By his own surviving account,[lower-alpha 5] he was an itinerant poet who left his native land at the age of 25 and then lived 67 years in other Greek lands, dying at or after the age of 92.[3] Although ancient testimony notes that he buried his sons, there is little other biographical information about him or his family that can be reliably ascertained.[3]

It is considered likely Xenophanes' physical theories were influenced by the Milesians. For instance, his theory that the rainbow is clouds is on one interpretation seen as a response to Anaximenes's theory that the rainbow is light reflected off of clouds.[4]

Poems

Knowledge of Xenophanes' views comes from fragments of his poetry that survive as quotations by later Greek writers. Unlike other pre-socratic philosophers such as Heraclitus or Parmenides, who only wrote one work, Xenophanes wrote a variety of poems, and no two of the fragments can positively be identified as belonging to the same text.[5] According to Diogenes Laertius[lower-alpha 7], Xenophanes wrote a poem on the foundation of Colophon and Elea, which ran to approximately 2000 lines.[5] Later testimony also suggests that his collection of satires was assembled in at least five books.[6] Although many later sources attribute a poem titled "On Nature" to Xenophanes, modern scholars doubt this label, as it was likely a name given by scholars at the Library of Alexandria to works written by philosophers that Aristotle had identified as "phusikoi" who studied nature.[5]

Satires

The satires are called Silloi by late writers, and this name may go back to Xenophanes himself, but it may originate in the fact that the Pyrrhonist philosopher Timon of Phlius, the "sillographer" (3rd century BC), put much of his own satire upon other philosophers into the mouth of Xenophanes, one of the few philosophers Timon praises in his work.[7]

Xenophanes' surviving writings display a skepticism that became more commonly expressed during the fourth century BC. Several of the philosophical fragments are derived from commentators on Homer. He aimed his critique at the polytheistic religious views of earlier Greek poets and of his own contemporaries

To judge from these later accounts[lower-alpha 8], his elegiac and iambic poetry criticized and satirized a wide range of ideas, including Homer and Hesiod,[8] the belief in the pantheon of anthropomorphic gods and the Greeks' veneration of athleticism.

On Nature

There is no good authority that says that Xenophanes specifically wrote a philosophical poem.[7] John Burnet says that "The oldest reference to a poem Περὶ φύσεως is in the Geneva scholium on Iliad xxi. 196[lower-alpha 9], and this goes back to Crates of Mallus. We must remember that such titles are of later date, and Xenophanes had been given a place among philosophers long before the time of Crates. All we can say, therefore, is that the Pergamene librarians gave the title Περὶ φύσεως to some poem of Xenophanes." However, even if Xenophanes never wrote a specific poem title On Nature, many of the suriviving fragments deal with topics in natural philosophy such as clouds or rainbows, and it is thus likely that the philosophical remarks of Xenophanes were expressed incidentally in his satires.[7]

Philosophy

Although Xenophanes has traditionally been interpreted in terms of the Eleatics and Skeptics who were influenced by him and saw him as their predecessor and founder, modern scholarship has revealed him to be a highly original and distinct philosopher whose philosophy extends well beyond the influence he had on later philosophical schools.[9] As a social critic, Xenophanes composed poems on proper behavior at a symposium and criticized the cultural glorification of athletes.[9] Xenophanes sought to reform the understanding of divine nature by casting doubt on Greek mythology as relayed by Hesiod and Homer, in order to make it more consistent with notions of piety from Ancient Greek religion.[9] He composed natural explanations for phenomena such as the formation of clouds and rainbows rather than myths,[9] satirizing traditional religious views of his time as human projections.[10] As an early thinker in epistemology, he drew distinctions between the ideas of knowledge and belief as opposed to truth, which he believed was only possible for the gods.[9]

Social criticism

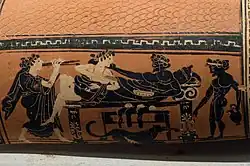

Xenophanes wrote a number of elegiac poems on proper conduct at a symposium,[9] the Ancient Greek drinking parties that were held to commemorate athletic or poetic victories, or to welcome young men into aristocratic society. The surviving fragments stress the importance of piety and honor to the gods[lower-alpha 10], and they discourage drunkenness[lower-alpha 11] and intemperance, endorsing moderation and criticism of luxury and excess[lower-alpha 12]. Xenophanes also rejected the value of athletic victories, stating that cultivating wisdom was more important.[lower-alpha 13].[9]

Divine Nature

Orphism and Pythagorean philosophy introduced into the Greek spirituality the notions of guilt and pureness, causing a dichotomic belief between the divine soul and the mortal body. This doctrine is in contrast with the traditional religions as espoused by Homer and Hesiod.[11] God moves all things, but he is thought to be immobile, characterized by oneness[lower-alpha 14][12] and unicity, eternity,[lower-alpha 15] and a spiritual nature which is bodiless and isn't anthropomorphic.[lower-alpha 16] He has a free will and is the Highest Good, he embodies the beauty of the moral perfection and of the absence of sin.[11]

Xenophanes espoused a belief that "God is one, supreme among gods and men, and not like mortals in body or in mind." He maintained that there was one greatest God. God is one eternal being, spherical in form, comprehending all things within himself, is the absolute mind and thought,[lower-alpha 17] therefore is intelligent, and moves all things, but bears no resemblance to human nature either in body or mind. While Xenophanes rejected Homeric theology, he did not question the presence of a divine entity; rather his philosophy was a critique on Ancient Greek writers and their conception of divinity.[13] Regarding Xenophanes' positive theology five key concepts about God can be formed. God is: beyond human morality, does not resemble human form, cannot die or be born (God is divine thus eternal), no divine hierarchy exists, and God does not intervene in human affairs.[13]

Natural Philosophy

Xenophanes' understanding of divine nature as separate and uninvolved in human affairs motivated him to come up with naturalistic explanations for physical phenomena.[9]

Xenophanes was likely the first philosopher to come up with an explanation for the manifestation of St. Elmo's fire that appears on the masts of ships when they pass through clouds during a thunderstorm. Although the actual phenomenon behind St. Elmo's fire would not be understood until the discovery of static electricity in the modern era, Xenophanes' explanation, which attempted to explain the glow as being caused by agitations of small droplets of clouds[lower-alpha 18] was unique in the ancient world.[14]

In Xenophanes' cosmology, there is only one boundary to the universe,[15] the one "seen by our feet"[lower-alpha 19]. Xenophanes believed that the earth extended infinitely far down, as well as infinitely far in every direction.[15] A consequence of his belief in an infinitely extended earth was that rather than having the sun pass under the earth at sunset, Xenophanes believed that the sun and the moon traveled along a straight line westward,[lower-alpha 20] after which point a new sun or moon would be reconstituted after an eclipse.[lower-alpha 21][15] While this potentially infinite series of suns and moons traveling would likely be considered objectionable to modern scientists,[15] this means that Xenophanes understood the sun and moon as a "type" of object that appeared in the sky, rather than a specific individual object that reappeared every new day.[15]

Xenophanes concluded from his examination of fossils of sea creatures that were found above land[lower-alpha 22] that water once must have covered all of the Earth's surface.[16] He used this evidence to conclude that the arche or cosmic principle of the universe was a tide flowing in and out between wet and dry, or earth (γῆ) and water (ὕδωρ). These two extreme states would alternate between one another, and with the alternation human life would become extinct, then regenerate (or vice versa depending on the dominant form).[17] The argument can be considered a rebuke to Anaximenes' air theory.[17] The idea of alternating states and human life perishing and coming back suggests he believed in the principle of causation, another distinguishing step that Xenophanes takes away from Ancient philosophical traditions to ones based more on scientific observation.[16] This use of evidence was an important step in advancing from simply stating an idea to backing it up by evidence and observation.[17]

Epistemology

Xenophanes is one of the first philosophers to show interest in epistemological questions as well as metaphysical ones. He held that there actually exists an objective truth in reality,[lower-alpha 23] but that as mere mortals, humans are unable to know it.[lower-alpha 24] He is also credited with being one of the first philosophers to distinguish between true belief and knowledge,[lower-alpha 25] as well as acknowledge the prospect that one can think he knows something but not really know it.[18]

His verses on skepticism are quoted by Sextus Empiricus as follows:

Yet, with regard to the gods and what I declare about all things:

No man has seen what is clear nor will any man ever know it.

Nay, for even should he chance to affirm what is really existent,

He himself knoweth it not ; for all is swayed by opining.[lower-alpha 26]

Due to the lack of whole works by Xenophanes, his views are difficult to interpret, so that the implication of knowing being something deeper ("a clearer truth") may have special implications, or it may mean that you cannot know something just by looking at it.[18] It is known that the most and widest variety of evidence was considered by Xenophanes to be the surest way to prove a theory.[16]

Legacy and influence

Xenophanes's influence has been interpreted variously as "the founder of epistemology, a poet and rhapsode and not a philosopher at all, the first skeptic, the first empiricist, a rationalist theologian, a reformer of religion, and more besides."[19] Karl Popper read Xenophanes as an early precursor of critical rationalism, saying that it is possible to act only on the basis of working hypotheses—we may act as if we knew the truth, as long as we know that this is extremely unlikely.[20]

Influence on Eleatics

Many later ancient accounts associate Xenophanes with the Greek colony in the Italian city of Elea, either as the author of a poem on the founding of that city,[lower-alpha 27] or as the founder of the Eleatic school of philosophy,[lower-alpha 28] or as the teacher of Parmenides of Elea.[lower-alpha 29] Others associate him with Pythagoreanism. However, modern scholars generally believe that there is little historical or philosophical justification for these associations between Pythagoras, Xenophanes, and Parmenides as is oft alleged in succession of the so-called "Italian School".[3] It had similarly been common since antiquity to see Xenophanes as the teacher of Zeno of Elea, the colleague of Parmenides, but common opinion today is likewise that this is false.[21]

In his ninety-second year he was still, we have seen, leading a wandering life, which is hardly consistent with the statement that he settled at Elea and founded a school there, especially if we are to think of him as spending his last days at Hieron's court. It is very remarkable that no ancient writer expressly says he ever was at Elea, and all the evidence we have seems inconsistent with his having settled there at all.[22]

Influence on Pyrrhonism

Xenophanes is sometimes considered the first skeptic in Western philosophy.[23][lower-alpha 30] Xenophanes's alleged skepticism can also be seen as a precursor to Pyrrhonism. Sextus quotes Pyrrho's follower Timon as praising Xenophanes and dedicating his satires to him, and giving him as an example of somebody who is not a perfect skeptic (like Pyrrho), but who is forgivably close to it.[24]

Eusebius quoting Aristocles of Messene says that Xenophanes was the founder of a line of philosophy that culminated in Pyrrhonism. This line begins with Xenophanes and goes through Parmenides, Melissus of Samos, Zeno of Elea, Leucippus, Democritus, Protagoras, Nessos of Chios, Metrodorus of Chios, Diogenes of Smyrna, Anaxarchus, and finally Pyrrho.[lower-alpha 31]

Pantheism

Because of his development of the concept of a "one god greatest among gods and men," Xenophanes is often seen as one of the first monotheists in Western philosophy of religion. However, the same referenced quotation refers to multiple "gods" who the supreme God is greater than.[25] This god "shakes all things" by the power of his thought alone. Differently from the human creatures, God has the power to give "immediate execution" (in Greek: to phren) and make effective his cognitive faculty (in Greek: nous).[lower-alpha 32]

The thought of Xenophanes was summarized as monolatrous and pantheistic by the ancient doxographies of Aristotle, Cicero, Diogenes Laertius, Sextus Empiricus, and Plutarch. More particularly, Aristotle's Metaphysics summarized his view as "the All is God."[lower-alpha 33] The pseudo-Aristotlelian treatise On Melissus, Xenophanes, and Gorgias also contains a significant testimony of his teachings.[lower-alpha 34] Pierre Bayle considered Xenophanes views similar to Spinoza.[26] Physicist and philosopher Max Bernhard Weinstein specifically identified Xenophanes as one of the earliest pandeists.[lower-alpha 35]

Xenophanes's view of an impersonal god seemed to influence the pre-socratic Empedocles, who viewed god as an incorporeal mind.[28] However, Empedocles called Xenophanes's view that Earth is flat and extends downward forever to be foolishness.[29][30]

Notes

- (DK 21A1)

- Diogenes Laertius, ix. 18-20 (DK 21A1)

- Diogenes Laertius

- Diogenes Laertius, ix. 1; Aristotle, Metaphysics

- (DK 21B8)

- (DK 21B8)

- DK 28A1

- Diogenes Laertius, ix. 18-20 (DK 21A1)

- DK 21B30

- To hymn the praises of the Gods; and so / With pure libations and well-order'd vows / To win from them the power to act with justice / For this comes from the favour of the Gods;(DK 21B1)

- And never let a man a goblet take / And first pour in the wine; but let the water / Come first, and after that, then add the wine.(DK 21B5)

- They learnt all sorts of useless foolishness / From the effeminate Lydians, while they / Were held in bondage to sharp tyranny / They went into the forum richly clad / In purple garments, in numerous companies / Whose strength was not less than a thousand men / Boasting of hair luxuriously dress'd / Dripping with costly and sweet-smelling oils.(DK 21B3)

- For wisdom far exceeds in real value / The bodily strength of man, or horses' speed;/ But the mob judges of such things at random; / Though 'tis not right to prefer strength to sense:(DK 21B2)

- "One god, the greatest among gods and men, neither in form like unto mortals nor in thought." (DK 21B23)

- DK 21B26

- DK 21B14-15, DK 21B16

- Diogenes Laertius, ix. 18-20 (DK 21A1)

- DK 21A39:"Those star-like apparitions mariners call the Dioskouroi—they are in reality clouds: small ones that glow because of some agitation."

- DK 21A28

- DK 21 A41a

- DK 21 A41a

- DK 21A33

- (DK 21B18)

- DK 21B34

- DK 21B34

- quoted by Sextus Empiricus,(DK 21B34)

- DK 28A1

- A8,30,36

- A2,A30,A31

- DK 21B49

- DK 21A49

- DK 21B25

- DK 21A30

- DK 21A28

- "Pandeistisch ist, wenn der Eleate Xenophanes (aus Kolophon um 580-492 v. Chr.) von Gott gesagt haben soll: "Er ist ganz und gar Geist und Gedanke und ewig", "er sieht ganz und gar, er denkt ganz und gar, er hört ganz und gar."[27]

References

- "Xenophanes" entry in Collins English Dictionary.

- Sound file

- Lesher 1992, p. 3-4.

- Xenophanes (January 2001). James H. Lesher (ed.). Fragments. University of Toronto Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780802085085.

- Mackenzie 2021, p. 24-27.

- DK 21B21a.

- Burnet 1892.

- Barnes 1982, p. 40.

- Lesher 2019.

- Johansen 1999, p. 49.

- Meza 2010, p. 55-57.

- Burnet 1892, p. 119.

- McKirahan 1994, p. 60-62.

- Mourelatos 2008, p. 134.

- Mourelatos 2008, p. 138-139.

- McKirahan 1994, p. 66.

- McKirahan 1994, p. 65-66.

- Osborne 2004, p. 66-67.

- Is God In the Clouds?: A Note on Xenophanes by Michael Sevel

- Popper 1998, p. 46.

- Lesher 1992, p. 102.

- Burnet 1892, p. 115.

- Xenophanes' Scepticism by James H. Lesher, Phronesis Vol. 23, No. 1 (1978), pp. 1-21

- A. A. Long. From Epicurus to Epictetus. p. 86.

- Lesher 2021.

- Bayle, Critical Dictionary, p. 574

- Weinstein 1910, p. 231.

- "Empedocles" Cambridge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1961) by Charles Kahn, p. 498

- DK 21B28

- DK31B39

Bibliography

Ancient Primary Sources

In the Diels-Kranz numbering for testimony and fragments of Pre-Socratic philosophy, Xenophanes is catalogued as number 21.

The most recent edition of this catalogue is Diels, Hermann; Kranz, Walther (1957). Plamböck, Gert (ed.). Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker (in Ancient Greek and German). Rowohlt. ISBN 5875607416. Retrieved 11 April 2022..

Biography

- A1.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - A2.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - A3.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - A4. Cicero. Academica. II.118.

- A5.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - A6. Pseudo-Lucian. Macrobii. 20.

- A7. Censorinus (1900). "On Old Age". De Die Natali. 15, 3.

- A8. Clement of Alexandria. . Stromata – via Wikisource.

- A9. Eusebius. Chronicon Paschale. Ol. 56.

- A10. Iamblichus. Iamblichi Theologoumena arithmeticae (in Latin).

Apothegems

- A11. Plutarch. "Sayings of Kings and Commanders". Moralia. Stephanus p.175c.

- A12. Aristotle. Rhetoric. Bekker 1399b.

- A13. Aristotle. Rhetoric. Bekker 1400b.

- A14. Aristotle. Rhetoric. Bekker 1377a.

- A15. Aristotle. Metaphysics. Bekker 1399b.

- A16. Plutarch. "On Compliancy". Moralia. 530e.

- A17. Plutarch. "On Common Conceptions against the Stoics". Moralia. Archived from the original on 2019-07-15.

Descriptions of Poems

- A18.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - A19.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - A20. Strabo. Geography.

- A21. Apuleius. Florida.

- A22. Proclus. Commentary on Hesiod's Works and Days.

- A23. Scholia.

- A24. Arius Didymus. Doxographi Graeci.

- A25. Cicero. Academica. II.74.

- A26. Philo. On Providence.

- A27. Athenaeus. Deipnosophistae. 632cd.

Doctrines

- A28. Pseudo-Aristotle (1936). "On Melissus, Xenophanes, Gorgias". Aristotle: Minor Works. Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press. Bekker p.977a-979a. ISBN 978-0-674-99338-9. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- A29. Plato. Sophist. Stephanus 242c-d.

- A30. Aristotle. Metaphysics. Bekker 986b.

- A31. Simplicius of Cilicia. Commentary on Aristotle's Physics.

- A32. Pseudo-Plutarch. "Opinions of the Philosophers". Moralia. Book II.4.

- A33. Hippolytus of Rome. Refutation of All Heresies. p. – via Wikisource.

- A34. Cicero. Academica. II.118.

- A35. Pseudo-Galen. History of Philosophy.

- A36-46. Aetius. Placita.

- A47. Aristotle. On the Heavens. Bekker 294a.

- A48. Pseudo-Aristotle. On Marvellous Things Heard. Bekker 833a.

- A49. Aristocles of Messene. On Philosophy. Quoted in Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica Book 14 Chapter XVII.

- A50. Macrobius. Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis (in Latin). – via Wikisource.

- A51. Tertullian. Treatise On the Soul. Chapter XLIII.

- A52. Cicero. De Divinatione.

Fragments - Elegies

- B1. Athanaeus. Deipnosophistae. 11.462c.

- B2. Athanaeus. Deipnosophistae. 10.413f.

- B3. Athanaeus. Deipnosophistae. 12.526a.

- B4. Julius Pollux. Onomasticon.

- B5. Athanaeus. Deipnosophistae. 11.782a.

- B6. Athanaeus. Deipnosophistae. 9.368e.

- B7.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - B8.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - B9. Etymologicum Genuinum. γῆρας.

Fragments - Silloi

- B10. Aelius Herodianus. On Doubtful Syllables. 296.6.

- B11. Sextus Empiricus. Against the Physicists. Book I.193.

- B12. Sextus Empiricus. Against the Grammarians. Book I.289.

- B13. Aulus Gellius. Attic Nights. 3.11.

- B14-15. Clement of Alexandria. Stromata. p. – via Wikisource.

- B16. Clement of Alexandria. Stromata. p. – via Wikisource.

- B17. Scholia to Aristophanes Knights.

- B18. Stobaeus. Eclogues. Book I/8/2.

- B19.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:1. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:1. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - B20.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:1. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:1. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - B21. Scholia to Aristophanes Peace.

- B21a. Oxyrhynchus Papyri. 1087.40.

- B22. Athenaeus. Deipnosophistae. 2.54e.

Fragments - On Nature

- B23. Clement of Alexandria. Stromata. 5.109.

- B24. Sextus Empiricus. Against the Physicists. Book I.144.

- B25. Simplicius of Cilicia. Commentary on Aristotle's Physics. 23.19.

- B26. Simplicius of Cilicia. Commentary on Aristotle's Physics. 23.10.

- B27. Theodoretus. Treatment of Greek Conditions.

- B28. Achilles Tatius. Introduction to the Phaenomena of Aratus.

- B29. John Philoponus. Commentary on Aristotle's Physics. 1.5.125.

- B30. Geneva Scholia to Iliad. 21.196.

- B31. Heraclitus (commentator) (2005). Homeric Problems. Society of Biblical Literature. 44.5. ISBN 978-1-58983-122-3. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- B32. Allen, Thomas William (1931). The Homeric Scholia. H. Milford. BLT Iliad 11.27.

- B33. Sextus Empiricus. Against the Physicists. Book II.314.

- B34. Sextus Empiricus. Against the Logicians. Book I.49.

- B35. Plutarch. "Table Talk". Moralia. Stephanus p.746b.

- B36. Aelius Herodianus. On doubtful syllables. 296.9.

- B37. Aelius Herodianus. On peculiar style. 30.

- B38. Aelius Herodianus. On peculiar style. 41.5.

- B39. Julius Pollux. Onomasticon.

- B40. Etymologicum Genuinum. βάτραχος.

- B41. John Tzetzes. Scholia to Dionysius Periegetes. 940.

- B42. Aelius Herodianus. On peculiar style. 41.5.

- B45. Scholia to On Epidemics. 1.13.3.

Imitation

- C1. Euripides. Herakles (Euripides).

- C2 Athanaeus. Deipnosophistae.

Modern Criticism

- Popper, Karl (1998). The World of Parmenides: Essays on the Presocratic Enlightenment. Psychology Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-415-17301-8. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

Translations of the Fragments with Commentary

- Burnet, John (1892). "Science and Religion". Early Greek Philosophy. A. and C. Black. pp. 83–129. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Fairbanks, Arthur (1898). The first philosophers of Greece. New York : Scribner. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Graham, Daniel W. (2010). "Xenophanes". The Texts of Early Greek Philosophy: The Complete Fragments and Selected Testimonies of the Major Presocratics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–134. ISBN 978-0-521-84591-5. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Kirk, G. S.; Raven, J. E.; Schofield, M. (29 December 1983). The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27455-5. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Lesher, James H. (1992). Xenophanes of Colophon: Fragments : a Text and Translation with a Commentary. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8508-5. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- McKirahan, Richard D. (1994). "Xenophanes of Colophon". Philosophy Before Socrates: An Introduction with Texts and Commentary. Hackett Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87220-175-0. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Trzaskoma, Stephen M.; Smith, R. Scott; Brunet, Stephen; Palaima, Thomas G. (1 March 2004). Anthology of Classical Myth: Primary Sources in Translation. Hackett Publishing. p. 433. ISBN 978-1-60384-427-7. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Weinstein, Max Bernhard (1910). Welt- und Lebenanschauungen; hervorgegangen aus Religion, Philosophie und Naturerkenntnis (in German). Litres. p. 231. ISBN 978-5-04-120710-6. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

Extended Studies and Reviews

- Barnes, Jonathan (1982). The Presocratic Philosophers. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05079-1. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Dalby, Andrew (2006). Rediscovering Homer. New York, London: Norton. p. 123. ISBN 0-393-05788-7.

- Edwards, M. J. (2005). "Xenophanes Christianus?". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. Duke University Press. 32 (3): 220. ISBN 9781351219143. ISSN 0017-3916. OCLC 8162351763. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014.

- Johansen, Karsten Friis (1999). A history of ancient philosophy: from the beginnings to Augustine. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780203979808.

- Lesher, James (2019). "Xenophanes". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Lesher, James (2021). "Xenophanes". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- Luchte, James (2011). Early Greek Thought: Before the Dawn. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0567353313.

- Mackenzie, Tom (2021). "Xenophanes". Poetry and poetics in the Presocratic philosophers : reading Xenophanes, Parmenides and Empedocles as literature. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 24–64. ISBN 9781108843935.

- Meza, Carlos Gustavo Carrasco (2010). "La tradición en la teología de Jenófanes" [Tradition in Xenophanes' theology] (PDF). Byzantion nea hellás (in Spanish and English). Santiago: University of Chile (29): 55, 57. doi:10.4067/S0718-84712010000100004 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISSN 0718-8471. OCLC 7179329409. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Mourelatos, Alexander (2008). "The Cloud - Astrophysics of Xenophanes and Ionian Material Monism". The Oxford Handbook of Presocratic Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 134–168. ISBN 978-0-19-514687-5.

- Osborne, Catherine (22 April 2004). Presocratic Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. pp. 61–79. ISBN 978-0-19-157822-9. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Warren, James (2007). Presocratics. Acumen. ISBN 978-1-84465-091-0. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

Further reading

| Library resources about Xenophanes |

| By Xenophanes |

|---|

- Curd, Patricia (2020). "Presocratic Philosophy". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Classen, C. J. 1989. "Xenophanes and the Tradition of Epic Poetry". In Ionian Philosophy. Edited by K. Boudouris, 91–103. Athens, Greece: International Association for Greek Philosophy.

- "Xenophanes". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

External links

- Xenophanes of Colophon by Giannis Stamatellos

- Xenophanes of Colophon - Primary and secondary resources (link broken, June 9, 2019, archived page)

- J. Lesher, Presocratic Contributions to the Theory of Knowledge, 1998

- U. De Young, "The Homeric Gods and Xenophanes' Opposing Theory of the Divine", 2000