Mississippian stone statuary

The Mississippian stone statuary are artifacts of polished stone in the shape of human figurines made by members of the Mississippian culture (800 to 1600 CE) and found in archaeological sites in the American Midwest and Southeast.[1] Two distinct styles exist; the first is a style of carved flint clay found over a wide geographical area but believed to be from the American Bottom area and manufactured at the Cahokia site specifically; the second is a variety of carved and polished locally available stone primarily found in the Tennessee-Cumberland region and northern Georgia (although there are lone outliers of this style in other regions). Early European explorers reported seeing stone and wooden statues in native temples, but the first documented modern discovery was made in 1790 in Kentucky, and given as a gift to Thomas Jefferson.[1]

History

Archaeologists have divided what is known about Mississippian culture religious practices into three major "cult" manifestations. The Chiefly Warrior cult, the Earth/fertility cult, and an Ancestor cult.[2] The stone statues found seem to represent different aspects from each of these 3 major divisions of Mississippian religious life. The Cahokian-style pieces represent figures from the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex and earth/fertility goddesses. The Tennessee-Cumberland statues seem to represent venerated ancestors (possibly Lucky Hunter and Corn Woman), and a third variety represents Old Woman or Spider Grandmother, a creator and fertility goddess. Early European explorers describe stone statues as being kept in mortuary temples or shrines, frequently on top of platform mounds. Over the next several hundred years the statues disappeared from history, many of them hidden by Native Americans to protect their sacred objects. The statues began to surface again during the 18th and 19th centuries as European American farmers began plowing the fertile river valleys of the south and midwest, and later as looters and then archaeologists began to dig into the burial mounds.

Cahokia style

This style of statuary is found at Cahokian sites in western Illinois and eastern Missouri, at Spiro and other Caddoan Mississippian sites[3] in eastern Oklahoma and northwestern Louisiana, and various other sites throughout the American southeast. For many years the statues were thought to have been produced locally at the sites in which they were discovered, but recent scientific analysis (X-ray diffraction, sequential acid dissolution, and inductively coupled plasma analyses)[4] has shown all of the statues to have been produced from a flint clay only found in the vicinity of St. Louis, Missouri.[2][5] The particular pipestone used by the artists of Cahokia has a distinctive combination of a lithium bearing chlorite, abundant boehmite (an aluminium oxyhydroxide) and a heavy-metal phosphate mineral suite.[5] It is believed that the objects were considered to be valuable trade and religious objects, and spread far and wide from their place of production in the American Bottom. Many of the figurines depict mythological characters from the Chiefly Warrior cult and the Earth/fertility cult. Most flint clay figurines found outside Cahokia represent male figures from the Chiefly Warrior Cult, as opposed to items found near Cahokia which mostly represent female figures from the Earth/fertility cult.[6]

BBB Motor Site figurines

.jpg.webp)

The BBB Motor Site, a major second tier ceremonial site of Cahokia during the Stirling Phase, has produced two notable examples of this style. The first, the "Birger figurine", depicts a kneeling woman wearing a pack on her back and using a hoe to till the back of a feline headed serpent on which she is squatting. The tail of the serpent splits and transforms into gourd flowers, vines and fruit. The Underwater Serpent, with its associations with the Underworld, is thought to represent the fertility of the Earth.[7] The second example from the site is the "Keller figurine", which depicts a woman with long straight hair and cranial deformation, wearing a wrap-around skirt and kneeling on a platform. The platform is divided by sections and covered with striations that are thought to represent ears of maize. The women's hands rest on a box-like object which may be a basket. A maize stalk rises on the right side of the basket, through the right hand and along the arm and around the back of the figure's head. This figurine is also thought to represent the connection of vegetation and fertility, female deities and the Earth.[2] The Keller figurine is 14 centimeters (5.5 in) in height.[8]

Sponemann Site figurines

The Sponemann Site, another Sterling Phase second tier ceremonial site of Cahokia, has produced three flint clay figurines, although these had been ritually broken or "killed" before burial. The "Sponemann figurine", at 15 centimeters (5.9 in), is only partially recovered. What remains is the head, upper torso and arms of a female with detailed facial features very like those of the Birger figurine. The figure's outstretched arms hold vegetation (possibly maize or sunflower plants), which curls up onto the head. The "Willoughby figurine" is also incomplete, with only parts of the head, torso and lower body surviving. The figure, obviously a female from the surviving anatomy of the torso, wears a wrap around skirt and holds plants and woven cane baskets. The presence of the vines and baskets may connect the figure with rites from the Green Corn Ceremony. The surviving fragments of the "West figurine" show a female with a rattlesnake coiled around her head as a turban. Not much else survives of this specimen, although enough of the torso exists to tell the figurine is female.[2]

The Spiro pipes

Archaeologists believe several pipes found at the site may be heirlooms that made their way from Cahokia to Spiro in the late 13th century as the cultural center collapsed.[9] Several large flint clay pipes were found in the "Craig Mound" or "Great Mortuary" mound at Spiro in the 1930s. The "Lucifer pipe" shows a nude man with an oversized head holding a deer head in his left hand and a fringed object of some sort in his right. The pipe has a hole in the back for the insertion of a tube so it could function as a pipe. It is 23 centimeters (9.1 in) tall.[9] Another intriguing find from the Craig Mound is the "Resting Warrior" or "Big Boy pipe". Archaeologist have argued that the figure may represent Red Horn, a mythic demigod from many Native American stories. The 26 centimeters (10 in) figure sits cross legged, with his hands on his knees. He wears a cape of feathers on his back, similar to actual examples found in the Craig Mound during excavations. He has Long-nosed god maskette earrings, strings of beads around his neck,[10] and strapped to his head is a sacred bundle incorporating what is thought to be a copperplate with an Ogee motif at its center.[11] The hair is done up in a bun on the back of the figures head and a long braid over the left shoulder. The earrings and the braid are the reason many archaeologist identify the figure as Red Horn. The "Conquering Warrior"[8] effigy pipe shows the more brutal and militaristic side of Mississippian culture. The 24 centimeters (9.4 in) figure depicts a warrior in ritual regalia leaning over a crouching victim and either hitting him in the face with a war club[10] or decapitating him.[5] Another effigy pipe from Spiro depicts a crouching man smoking from a frog effigy pipe, and is 20.5 centimeters (8.1 in) tall and 36.5 centimeters (14.4 in) long.[9] While most of the pipes from the Spiro site depict males, the "Figure at mortar" seems to show a female. Although the figure lacks definitive sexual characteristics, the fact that it is grinding maize and details of its costumes suggest it is indeed a representation of a female. The figure is shown kneeling on an oval base and has its hair pulled back behind its ears. The figurine is thematically very close to the Birger and Keller figurines found in the American Bottom.[2] This pipe is on display at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C.

Gahagan

Similar examples have also been discovered at other Caddoan Mississippian sites, most notably the Gahagan site which had two effigy pipes.[3] Several of these pipes are on display at the Native American gallery of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History in Norman, Oklahoma.

Other examples

Other sites have produced single examples of the Cahokia flint clay statues and pipes, in locations scattered throughout the American South.

East St. Louis

A frog effigy pipe was found in East St. Louis, St. Clair County, Illinois. It measures 13 centimeters (5.1 in) in height by 14.5 centimeters (5.7 in) in length.[8]

Exchange Avenue figurine

The most recent addition to the corpus of Cahokian flint clay figurines. It is a 6 inches (15 cm) in height female figurine found during a massive archaeological dig at the old National Stock Yards in National City, Illinois in the summer of 2010. The dig was being done in preparation for a new $670 million Mississippi River bridge project. The sitting figure has long hair which winds down her back, a skirt, and is holding forward a conch shell that is believed to have connections with the watery underworld of the Mississippian cosmology. The back of the figurine shows charring from a fire.[12][13]

Guy Smith Village site

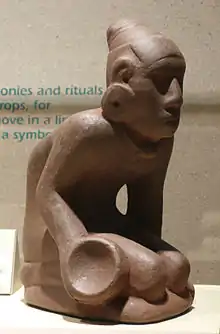

A 9.5 centimeters (3.7 in) in height effigy pipe known as the "Crouching warrior". The male figure has his head cocked to the right and has a large rectangular shield like shape on his right arm. It was found at the Guy Smith Village site (11J49) in Jackson County, Illinois.[8]

Hughes Site Chunkey player

The "Chunkey Player" is an 8.5 inches (22 cm) high by 5.5 inches (14 cm) wide effigy pipe[14] found at the Caddoan Mississippian Hughes Site (34 MS 4); 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Muskogee in Muskogee County, Oklahoma.[15] It is now part of the Henry Whelpley Collection at the St. Louis Science Center. The pipe depicts a kneeling male who is slightly leaning forward and in the process of rolling a chunkey stone with his right hand and holding two chunkey sticks in left. He is wearing large ear spools, has a necklace around his neck with a large bead attached, and an elaborate hat or hair style.[14]

Keesee figurine

A 17.5 centimeters (6.9 in) in height figurine that depicts a kneeling upright male figure who grasps a cylindrical object thought to be a rolled up sacred medicine bundle in his right hand and connected by the base there is a freestanding ceramic vessel placed in front of him. It is the only Cahokian flint clay figurine with such a detached element not directly connected to the human figure of the piece. Stylistically it is very similar to the "Chunkey player" pipe found in Muskogee County, Oklahoma; having very similar anatomical proportions, facial details, hairstyles, and pose. They are thought to possibly represent the same mythological figure (Redhorn or Morningstar) and are considered to have been made by the same artist. It was found in the early 20th century during the plowing of a cotton field south of Helena, Arkansas. The figure shows some damage; including a missing left arm, part of the left leg, and the left side of the head. This damage is thought to have happened when the figurine was "ritually killed" and deposited and not during its discovery during the plowing of the cotton field.[16]

Shiloh Indian Mounds site

In 1899 Cornelius Cadle, chairman of the Shiloh Park Commission, excavated Shiloh Indian Mounds Sites Mound C. He had a trench dug into the conical burial mound, and amongst the discoveries was a large stone effigy pipe in the shape of a kneeling man. It has since become the site's most famous artifact and is on display in the Tennessee River Museum in Savannah.[17][18] The pipe, now known as the "Crouching Man pipe" is 20.3 centimeters (8.0 in) in height.[8]

Starr Village and Mound Group site

The "Macoupin Creek figurine" (formerly the "Piasa Creek Figure pipe") measures 20.3 centimeters (8.0 in) in height[8] and depicts a shaman kneeling with a gourd rattle in one hand and a snake or snakeskin wrapped around his neck.[2] The figure also has conch shell and bead ear ornaments and a raccoon skin headdress. The pipe was discovered in a stone box grave at the Starr Village and Mound Group site in the Macoupin Creek Valley sometime late in the nineteenth century. Because of the age of the burial (Early Sand Prairie Phase 1250 CE) and the time of the statues believed manufacture (Stirling Phase 1050 to 1200 CE) it is posited that the figure was a curated heirloom, buried long after its manufacture and in a region not normally associated with Mississippian settlements.[19] It is now in the collection of the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.[8]

Twin Mounds site

A 17.8 centimeters (7.0 in) kneeling male figure pipe was excavated from the Twin Mounds Site in Ballard County, Kentucky.[8]

Westbrook figurine

Once known as the "McGehee figure pipe",[2] and now as the "Westbrook Figurine" after its current owner Dr. Kent Westbrook,[20] it depicts a female figure kneeling on her knees with a basket behind her. The figure has sunflowers on her back and two maize plants sprout from her outstretched hands. The effigy pipe is 18 centimeters (7.1 in) by 18 centimeters (7.1 in) by 14 centimeters (5.5 in). It was found during amateur excavations in the late 1960s at a site close to the mouth of the Arkansas River known as the DeSoto Mound (3 DE 24, also known as the Opossum Fork Bayou Mound or the Richland Mound) in Desha County, Arkansas[21][8] In July 2003 archaeologists from the Midcontinental Archaeometry Working Group of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign conducted portable infrared mineral analyzer (PIMA) and Hunter color analyses on the figure to determine its origins. Their analysis determined that the pipe was made from a cookeite-boehmite phosphate (CBP) flint clay from Missouri that may have come from a quarry as near to Cahokia as St. Louis County.[20]

Gallery of Cahokian flint clay statues

.jpg.webp) Birger figurine

Birger figurine "Figure at mortar" pipe from Spiro, on display at N.M.A.I.

"Figure at mortar" pipe from Spiro, on display at N.M.A.I. Reproduction of the "Conquering Warrior" effigy pipe from Spiro

Reproduction of the "Conquering Warrior" effigy pipe from Spiro "Resting Warrior", side view effigy pipe from Spiro

"Resting Warrior", side view effigy pipe from Spiro_effigy_pipe_HRoe-2010.jpg.webp) Effigy pipe of figure smoking from a frog effigy pipe from Spiro

Effigy pipe of figure smoking from a frog effigy pipe from Spiro Effigy pipe from Spiro, of a man smoking a pipe

Effigy pipe from Spiro, of a man smoking a pipe

Tennessee-Cumberland style

This style of statuary is found in northern Georgia, the Tennessee River Valley area around Nashville, Tennessee and on into western Tennessee and Kentucky, and southern Indiana. Examples of this style are also known from wooden and ceramic versions. The function and symbology of this statuary seems to have been fundamentally different from the Cahokian flint clay pieces. Three different types are identified, a pair with a male and female example and an old woman/fertility goddess. It is theorized that the couple may represent the primordial ancestral couple from which a group claimed descent. Males are often represented without obvious clothing, sitting crosslegged with their hands resting on their knees. Some examples are resting on one leg with the other drawn up before them. Their hair is done up in a bun on the back of the head, and shows qualities in common with other depictions of warriors. The females are usually shown with small breasts, wearing a wrap around skirt, sitting with their legs tucked under them and with their hair pulled back and falling down their backs, sometimes with braids. The third example is very similar to the female of the first examples but has 2 additional characteristics. This figure usually has her hands resting on its projecting stomach and has its sexual organs defined. All of the figures show a general concentration of refinement on the heads and upper torsos, with some even going so far as to barely have the lower body represented at all.[1] The earliest documented piece known to have been found was near the Cumberland River southwest of Lexington, Kentucky in 1790. An unknown farmer discovered the kneeling figure while plowing. It was obtained by Judge Harry Innes, the first United States federal judge in Kentucky, who made a gift of the statuette to Thomas Jefferson in July 1790. This 9.75 inches (24.8 cm) example was the first of five that Jefferson eventually collected and kept on display at Monticello.[1] Jefferson also owned and displayed in Monticello's entrance hall a male and female pair. They were found in Tennessee on a high bluff overlooking the Cumberland River and in 1799 sent to Jefferson by Morgan Brown, a lieutenant during the Revolutionary War. Although they were sent from Palmyra, Tennessee, it is unclear if they were found there. Brown informed Jefferson that:

They were found on a high bluff on the north side of Cumberland river standing side by side facing to the East, the tops of their heads about six inches under the surface of the earth; there were two large mounds a little to the West of them and a quantity of human bones under and near them.

— - Morgan Brown 1799[22]

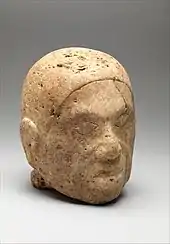

Another of the statues was a "head", approximately 18.4 centimeters (7.2 in) by 15.2 centimeters (6.0 in), purchased by Captain Stockton in the estate sale after Jeffersons death. One of his descendants sold the head to Dr. William C. Dabney and it eventually was made a gift to the Smithsonian Institution in 1875.[22] After Jeffersons death and the sale of his home, the other statues passed through several more hands before disappearing from history.[1]

Middle Tennessee region

The most numerous examples of this style are found in the Middle Tennessee region, mostly within the area between the Tennessee and Cumberland River Valleys, with more than fifty currently known. Three of the most productive sites in this area have been the Sellars site, the Castalian Springs Mound Site and the Beasley Mounds Site, with examples also being found at the Mound Bottom site and a unique cache of ceramic figurines at the Brick Church Pike Mound sites.[1]

The most well known statue from this region is the 47 centimeters (19 in) "Sandy" statue, the male half of a pair dug up in 1939 from the Sellars Mound in Wilson County, Tennessee. Now in the Frank H. McClung Museum in Knoxville,[23] it has been used on numerous book and magazine covers as well as on a U.S. postage stamp as part of the Art of the American Indians series.[24]

A paired set of male and female sandstone statues was discovered in March 1895 at the Link Farm site at the confluence of the Duck and Buffalo Rivers south of Waverly in Humphreys County, Tennessee. The site is also famous for being the location where the "Duck River cache" of chert artifacts was discovered in December 1894 in a low hillock at the site. The statues were found in the same but slightly deeper location. They were nicknamed "Adam" and "Eve" by their discoverers. The male statue is now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the female statue has been lost.[25][26]

Etowah

Ten examples of this style of statuary have been found at Etowah, but the most well known and most spectacular are the pair found in a log tomb in Mound C on January 19, 1954. Based on artifacts found with them the pair are believed to have been manufactured sometime between 1250 and 1375 CE, to have spent a time as ritual objects, and then to have been buried during the late Wilbanks Phase (1325–1375 CE). The statues were damaged when found, thought to have occurred during the hasty burial at a time of warfare or social upheaval.[1] The pair are carved from white marble and painted with red, black and green black pigments.[1] The male is 61 centimeters (24 in) high and the female 55.9 centimeters (22.0 in).[27] The pair is on display at the Etowah site museum with a diorama depicting its hasty burial.

Ohio River sites

Although the frequency of finds of this type drops dramatically outside of the geographical area for which they are named, significant examples have been found in other locations. Several have been found at Kincaid focus sites along the lower Ohio River. One of the best examples is from the Angel site in southern Indiana where a fluorite statue was excavated from Mound F in 1940. Dating of the mound suggests the statue was buried there between 1250 and 1400 CE. Another was discovered in the Tolu Site in western Kentucky in 1954. The 25 centimeters (9.8 in) fluorite piece is one of the most intricate yet found, and is the only known Tennessee-Cumberland style statue with a beaded forelock. Other finds in the area have been made at the Obion Mounds near Paris, Tennessee and the Ware Mounds site in Union County, Illinois. The Ware site example was found buried in Mound 1 by Thomas Perrine in 1873 and nicknamed "Anna". It is now part of the collection of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois.[1][28]

Significant outliers

Outside this region, which all have direct contact via the riverways to the Tennessee-Cumberland region, only two significant finds have been made. A 12 inches (30 cm) male figure was found at the Schugtown Mounds Site in Arkansas in 1933. Two statues were found at the Grand Village of the Natchez, one in 1820 and the other in excavations in Mound C in 1930. These two pieces are significant because the ethnographic history of the area records the use of stone temple statuary by the Natchez people, but these are the only known examples to have been found. And although there is no direct riverway connection to the Tennessee-Cumberland region as with most other finds, the area was connected to the Nashville Basin in ancient times by the Natchez Trace, a pre-European native trade route.[1]

Alternate materials

This specific image tradition may have been much more common than is represented in the archaeological record. Many smaller ceramic and stone statues have been found at sites throughout the region. Two very rare large wooden versions have also been found and it is hypothesized that there may have been many more that have not survived burial in the acidic soils of North America. One 32.5 centimeters (12.8 in) tall example is from the Craig Mound at Spiro (which also produced several prime examples of the Cahokia flint clay style), and is now on display at the Smithsonian Institution.[10] The other was found in a cave along the Cumberland River in Bell County, Kentucky in 1869 by an attorney from Pineville, Kentucky named Leonard Farmer. It was purchased by the Museum of the American Indian in 1916 and is now part of the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian.[29] The statue shows a figure very similar to the stone varieties, albeit with the lower body represented by a rectangular shape instead of legs, with the hands resting on it much like the stone versions. It was carved from yellow pine and is 61 centimeters (24 in) tall.[1] A unique cache of ceramic figurines was discovered in 1971 at the Brick Church Mound and Village Site in Nashville. The figurines were an adult male and adult female pair and two children of each sex, as well as pieces from additional figurines, totaling eleven figurines in all. They are now on display at the Frank H. McClung Museum of the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.[30]

Gallery of Tennessee-Cumberland statues

Prisoner pipe, limestone, 13th-14th century, believed to be from Mississippi

Prisoner pipe, limestone, 13th-14th century, believed to be from Mississippi Feline statuette excavated at the Moundville site

Feline statuette excavated at the Moundville site A second feline statuette example excavated at the Moundville site

A second feline statuette example excavated at the Moundville site Diorama at the Etowah Site showing the burial of statues and backs of actual statues

Diorama at the Etowah Site showing the burial of statues and backs of actual statues Diorama at the Etowah Site showing the hurried burial of 2 statues

Diorama at the Etowah Site showing the hurried burial of 2 statues

See also

References

- Kevin E. Smith; James V. Miller (2009). Speaking with the Ancestors-Mississippian Stone Statuary of the Tennessee-Cumberland region. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-5465-7.

- Thomas E. Emerson (1997). Cahokia and the Archaeology of Power. pp. 195–237. ISBN 0-8173-0888-1.

- Emerson, Thomas; Girard, Jeffrey (July 1, 2004). "DATING GAHAGAN AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR UNDERSTANDING CAHOKIA-CADDO INTERACTIONS". Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- Emerson, Thomas; Hughes, Randall E. (2000). "Figurines, Flint clay sourcing, The Ozark Highlands and Cahokian Acquisition". American Antiquity. 65 (1): 79–101. doi:10.2307/2694809. JSTOR 2694809. S2CID 161196850.

- Sarah Wisseman; Thomas Emerson; Randall Hughes; Kenneth Farnworth (April 29, 2008), Provenance studies of Midwestern pipestones using a portable spectrometer (PDF), Illinois State Archaeological Survey, archived from the original (PDF) on July 12, 2010, retrieved October 19, 2010

- Alt, Susan M.; Pauketat, Timothy R. (August 26, 2007). "Sex and the Southern Cult". In Adam King (ed.). Southeastern Ceremonial Complex:Chronology, Content, Context. University of Alabama Press. pp. 243–246. ISBN 978-0-8173-5409-1.

- "Mississippian beliefs" (article). Illinois State Museum. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- Townsend, Richard F.; Sharp, Richard V., eds. (October 11, 2004). Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10601-5.

- "Spiro and the Arkansas Basin" (article). University of Texas at Austin. August 6, 2003. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- "Mississippian World" (article). University of Texas at Austin. August 6, 2003. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- Sharp, Robert V. (2013), Middle Cumberland Female Effigies and the Portal to the Beneath World, p. 30, retrieved January 21, 2018

- Pawlaczyk, George (July 20, 2010). "900-year-old figurine uncovered in Illinois". American Archaeologist. Archived from the original (article) on September 1, 2010. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

- Sharp, Robert V. (2013), Middle Cumberland Female Effigies and the Portal to the Beneath World, p. 4, retrieved January 21, 2018

- Power, Susan C. (2004). Early Art of the Southeastern Indians:Feathered Serpents & Winged Beings. University of Georgia Press. pp. 123–125. ISBN 978-0-8203-2501-9.

- Emerson, Thomas E.; Hughes, Randall E.; Hynes, Mary R.; Wisseman, Sarah U. (2003). "The Sourcing and Interpretation of Cahokia-Style Figurines in the Trans-Mississippi South and Southeast". American Antiquity. Society for American Archaeology. 68 (2): 287–313. doi:10.2307/3557081. JSTOR 3557081. S2CID 163212264.

- Sharp, Robert V. (2014), Sacred Narratives of Cosmic Significance: The Place of the Keesee Figurine in the Mississippian Mythos, retrieved January 21, 2018

- "Shiloh Indian Mounds" (article). National Park Service. July 14, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- "Tennessee River Museum". TourHardinCounty.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- Emerson, Thomas E.; Lewis, R. Barry, eds. (October 15, 1999). Cahokia and the Hinterlands: Middle Mississippian Cultures of the Midwest. University of Illinois Press. pp. 89–91. ISBN 978-0-252-06878-2.

- Emerson, Thomas; Hughes, Randall E. (2003). "PIMA and Hunter Color Analyses on the Westbrook Cahokia Figurine and Bound Warrior Pipe" (PDF). Midcontinental Archaeometry Working Group, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2010.

- Colvin, Matthew H. (2012). "OLD-WOMAN-WHO-NEVER-DIES: A Mississippian survival in the Hidatsa world": 48–50. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Carved Stone Heads (Sculpture)". Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia. n.d. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- "Wilson County, Tennessee" (feature). Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- "ART OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN STAMPS, POSTAL CARDS, TO CELEBRATE DIVERSE EXPRESSIONS OF NATIVE AMERICAN ART". United States Postal Service. July 23, 2004. Archived from the original (letter) on March 8, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- "Link Farm State Archaeological Area". Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation.

- Kevin E. Smith; James V. Miller (2009). Speaking with the Ancestors-Mississippian Stone Statuary of the Tennessee-Cumberland region. University of Alabama Press. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-0-8173-5465-7.

- Bostrom, Peter (May 31, 2005). "ETOWAH MOUNDS SITE PAINTED MARBLE STATUES, Page 1" (article). Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- "Catalog Number: 55500.nosub". Field Museum of Natural History.

- "Catalog number4/8069 : Human figure". National Museum of the American Indian. Retrieved May 10, 2012.

- Barker, Gary; Kuttruff, Carl (Summer 2010). Michael C. Moore (ed.). "A Summary of Exploratory and Salvage Archaeological Investigations at the Brick Church Pike Mound Site (40DV39), Davidson County, Tennessee" (PDF). Editors Corner. Tennessee Archaeology. Tennessee Council for Professional Archaeology. 5 (1).

External links

- Riches of the Classic Mississippian Civilization-Birger Figurine and connection to Earth Fertility cult

- Archaeology & the Native Peoples of Tennessee:MISSISSIPIAN PERIOD - AD 1000 to 1600

- Corn woman effigy pipe from Desha County, Arkansas

- Colvin, Matthew H. (2012). Old-Woman-Who-Never-Dies: A Mississippian survival in the Hidatsa World (PDF) (Master of Arts thesis). Texas State University–San Marcos. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- Ronan, Kristine (2017). "'Kicked About': Native Culture at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello". Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. 3 (2 (Fall 2017)).