Bisbee Riot

The Bisbee Riot, or the Battle of Brewery Gulch, occurred on July 3, 1919, between the black Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry and members of local police forces in Bisbee, Arizona.

| Part of Red Summer | |

July 4th US News coverage of the July 3, 1919 Bisbee Riot | |

| Date | July 3, 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Bisbee, Arizona, United States |

| Also known as | Battle of Brewery Gulch |

| Outcome | ~8 wounded |

Following a confrontation between a military policeman and some of the Buffalo Soldiers, the situation escalated into a street battle in Bisbee's historic Brewery Gulch. At least eight people were seriously injured, and fifty soldiers were arrested. This incident was unusual for being between police and military. Most other riots during the Red Summer of 1919 involved wide-scale white rioting against blacks, both sides civilians.[1][2]

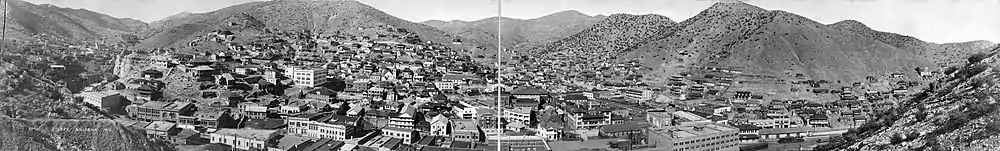

Background

In 1919, Bisbee had a population 20,000 and was home to white, black, Hispanic, Asian, and Native Americans. It was described by author Cameron McWhirter as a "remote... dusty frontier town," ten miles north of the Mexican border. The economy hinged on the extraction of copper ore from local mines. Because the demand for copper declined following the end of World War I, many of the miners in town became unemployed. Bisbee authorities were known for their harsh treatment of miners, many of whom were immigrants and minorities, and officials worked to suppress union organizing.

Two years before, in 1917, posses of Bisbee policemen and citizens had rounded up hundreds of miners and deported them to New Mexico by train. Morale was poor, and the town was strained socially. After the deportation, the federal government began surveilling Bisbee authorities, and the case against them was still working its way through the courts when the riot occurred. As a result, the most detailed information concerning the riot comes from memos and reports collected by the federal government.[1][2]

According to Jan Voogd, author of Race Riots and Resistance: The Red Summer of 1919, Bisbee was a "stratified white man's mining camp," and "highly race conscious". The town had rules prohibiting Mexican men from working underground in the mines; because this work paid higher, it was reserved for Welsh and Cornish immigrant miners.

Chinese immigrants were not allowed to stay in the town overnight. Blacks were limited to low-skilled jobs such as janitors. In 1919, Fort Huachuca was located about thirty-five miles west of Bisbee. Soldiers from the fort still made their way to the town. Its main street and red-light district, Brewery Gulch, was lined with brothels, saloons, and gambling halls. It was "notorious throughout the West". This was the site of fighting when unrest broke out.[1][2]

Mrs. Frederick Theodore Arnold, the wife of the fort's commander in 1918, wrote the following about the town in her diary:

The town was in a gulch just wide enough for one street [with] the stores and houses ... built mostly where rock is dug away, ... all one above the other like the cliff dwellers. Long flights of steps lead on up and up from house to house. It is the queerest town and the street ... runs right up-hill its whole winding length with a streetcar line ... there must be several thousand people there, and it is the busiest place you ever saw ... [There was] an enormous general store with everything from carpet tacks to oranges and hair nets.[1]

Riot

On July 3, 1919, the 10th Cavalry arrived in Bisbee from Fort Huachuca to march in the Independence Day parade the next day. While the regiment's white officers were attending a prearranged dance, the Buffalo Soldiers went to Upper Brewery Gulch, where the Silver Leaf Club was located.

According to Bisbee's Chief of Police, James Kempton, many of these soldiers were seen carrying their automatic service pistols, "most of them carrying them inside their blouses or in other places where they were not visible".[3] Kempton and Officer William Sherrill began to disarm the black soldiers, telling them that they could retrieve their weapons from the police station after they left town. Kempton and his officers were approached by one of the Tenth Cavalry's officers, who told the lawmen that the military allowed soldiers to carry their sidearms, if Kempton didn't object. Kempton said that he did mind. Allegedly the officer ordered the Tenth's troopers not to leave camp armed. At least some soldiers ignored this, if they were aware of it at all.[4]

Later that night, at about 9:30 pm, George Sullivan, a white military policeman (MP) from the 19th Infantry, got into a fight with five drunken black soldiers outside the club. According to Sullivan, he exchanged hostile words with the soldiers, who drew their revolvers, hit him on the head, and took his weapon. Jan Voogd notes that several citizens came to Sullivan's aid, and validated his report of the encounter. She also says various sources agree that the soldiers went to the police station and reported the incident to Chief Kempton. Sensing more trouble, Kempton advised the soldiers to turn over their weapons, but the latter refused. After the soldiers left the station, the chief began to assemble a posse to "disarm all the negroes they could find".[1][2]

Among those that Kempton enlisted was Cochise County Deputy Sheriff Joseph B. Hardwick. He was an Oklahoma native who had once served time for manslaughter. Following his release, he moved his family to Arizona, settling in Cochise County. In 1917 he shot and killed a Mexican ranch hand for allegedly assaulting his daughter. Not long after that incident, Hardwick (who had once worked as a lawman in Washington state) was hired as an officer with the Bisbee Police Department. He first worked with James Kempton, then serving as a Sergeant with the police. In 1918, Hardwick wounded Joel Smith, who had opened fire on Hardwick with a shotgun during a spree in Upper Brewery Gulch. In January 1919, Hardwick accepted a commission as a deputy sheriff under Sheriff James McDonald and for the next several months helped patrol the more remote regions of Cochise County and nearby Douglas.[5]

The attempt to disarm the black federal soldiers resulted in a street battle, centered on Brewery Gulch, that lasted for over an hour. According to McWhirter, deputized white civilians participated in the fighting; however, Jan Voogd says there is little evidence that Bisbee's local residents played any significant role. Most of the whites involved were documented as city police officers, or Cochise County sheriffs and deputies. More than 100 shots were fired during the melee. Fighting ended around midnight, when fifty of the Buffalo Soldiers surrendered to the police. The remaining soldiers were put on horses and told to ride back to their camp at Warren, under escort by two police cars.[1][2]

Shortly after the column headed out, five soldiers who had stayed behind began arguing with some of the officers. During this, Deputy Joe Hardwick, who had a reputation as a gunman, pulled out his revolver and shot one of the soldiers in the lung.[1][2]

Aftermath

At least eight people were shot or seriously wounded in total: Four of the Buffalo Soldiers were shot, two were beaten, a deputy sheriff was "severely injured," and a Mexican-American bystander named Teresa Leyvas was struck in the head by a stray bullet. In the Army's official report of the incident, commander of the 10th Cavalry, Colonel Frederick S. Snyder, said that "local officials had planned deliberately to aggravate the negro troopers so that they would furnish an excuse for police and deputy sheriffs to shoot them down."

A Bureau of Investigation report said that

"many of the soldiers who were absolutely innocent... were roughly handled... and seriously injured. This was due largely to the activity of Deputy Sheriff Joe Hardwick, who has the reputation of being a gunman and who on this occasion almost completely lost his head."

Bureau of Investigation agents had been surveilling Industrial Workers of the World activity in Bisbee, as the federal government was worried about union organizing. They reported that "representatives" of the IWW were "coach[ing]" the Buffalo Soldiers on what to expect from Bisbee authorities, telling them about the deportation in 1917, and "suggesting that conflict was imminent".[1][2]

Ultimately, none of the Buffalo Soldiers was seriously punished for the fighting, at least not by the Army. The 10th Cavalry was permitted to march in the Independence Day parade, under close watch by white US cavalrymen, who had been sent to patrol the streets and prevent further conflict. The Buffalo Soldiers later returned to Fort Huachuca, and their lives were "unfazed" by the events of July 3, according to Voogd. McWhirter says that "[t]he Bisbee fighting, covered nationally, brought to the fore America's conflicting feelings about black participation in the war [World War I/Border War]. Whites demanded black loyalty, but never trusted it."[1][2]

Joe Hardwick, strongly criticized for his actions, returned to Douglas. Later he was involved in an altercation apparently stemming from the Bisbee Riot; he was soon transferred to Tombstone, Arizona. A few months later, Hardwick turned in his badge and accepted a commission as a Pinal County Deputy Sheriff. In March 1920, Hardwick killed a knife-wielding subject in the town of Superior, Arizona. Hardwick held a number of law enforcement jobs in Arizona for several more years and later became Chief of Police in Calexico, California. There he was known as the "Czar of Calexico" and engaged in a number of other shootings. His career as a lawman ended after he shot and wounded an unarmed produce dealer from Los Angeles.[6]

See also

References

- Voogd, Jan (2008). Race Riots and Resistance: The Red Summer of 1919. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1433100673.

- McWhirter, Cameron (2011). Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. Macmillan. pp. 90–92. ISBN 978-1429972932.

- Krugler, David F. 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back p. 54

- Dolan, Samuel K. Cowboys and Gangsters: Stories of an Untamed Southwest (TwoDot Books, 2016) ISBN 978-1442246690

- Dolan, Cowboys and Gangsters, pp. 17–21, 26–28

- Dolan, Cowboys and Gangsters pp. 37–39

_troops_return_colors_to_Union_League_Club._Men_draw_._._._-_NARA_-_533590.jpg.webp)