Henna

Henna (Arabic: حِنّاء) is a dye prepared from the plant Lawsonia inermis, also known as the henna tree, the mignonette tree, and the Egyptian privet,[1] and one of the only two species of the genus Lawsonia, with the other being Lawsonia odorata.

Henna can also refer to the temporary body art resulting from the staining of the skin using dyes from the henna plant. After henna stains reach their peak color, they hold for a few days, then gradually wear off by way of exfoliation, typically within one to three weeks.

Henna has been used since antiquity in ancient Egypt, ancient Near East and then the Indian subcontinent to dye skin, hair and fingernails, as well as fabrics including silk, wool, and leather. Historically, henna was used in West Asia including the Arabian Peninsula and in Carthage, other parts of North Africa, West Africa, Central Africa, the Horn of Africa and the Indian subcontinent.

The name henna is used in other skin and hair dyes, such as black henna and neutral henna, neither of which is derived from the henna plant.[2][3]

.jpg.webp)

Preparation and application

Body art

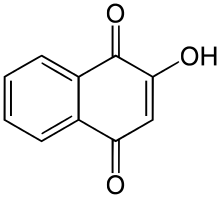

Whole, unbroken henna leaves will not stain the skin because the active chemical agent, lawsone, is bound within the plant. However, dried henna leaves will stain the skin if they are mashed into a paste. The lawsone will gradually migrate from the henna paste into the outer layer of the skin and bind to the proteins in it, creating a stain.

Since it is difficult to form intricate patterns from coarsely crushed leaves, henna is commonly traded as a powder[5] made by drying, milling and sifting the leaves. The dry powder is mixed with one of a number of liquids, including water, lemon juice, strong tea, and other ingredients, depending on the tradition. Many artists use sugar or molasses in the paste to improve consistency to keep it stuck to the skin better. The henna mix must rest between one and 48 hours before use in order to release the lawsone from the leaf matter. The timing depends on the crop of henna being used. Essential oils with high levels of monoterpene alcohols, such as tea tree, cajuput, or lavender, will improve skin stain characteristics. Other essential oils, such as eucalyptus and clove, are not used because they are too irritating to the skin.

The paste can be applied with many traditional and innovative tools, starting with a basic stick or twig. In Morocco, a syringe is common. A plastic cone similar to those used to pipe icing onto cakes is used in India. A light stain may be achieved within minutes, but the longer the paste is left on the skin, the darker and longer lasting the stain will be, so it needs to be left on as long as possible. To prevent it from drying or falling off the skin, the paste is often sealed down by dabbing a sugar/lemon mix over the dried paste or adding some form of sugar to the paste. After some time the dry paste is simply brushed or scraped away. The paste should be kept on the skin for a minimum of four to six hours, but longer times and even wearing the paste overnight is a common practice. Removal should not be done with water, as water interferes with the oxidation process of stain development. Cooking oil may be used to loosen dry paste.

Henna stains are orange when the paste is first removed, but darken over the following three days to a deep reddish brown due to oxidation. Soles and palms have the thickest layer of skin and so take up the most lawsone, and take it to the greatest depth, so that hands and feet will have the darkest and most long-lasting stains. Some also believe that steaming or warming the henna pattern will darken the stain, either during the time the paste is still on the skin, or after the paste has been removed. It is debatable whether this adds to the color of the result as well. After the stain reaches its peak color, it holds for a few days, then gradually wears off by way of exfoliation, typically within one to three weeks.

Natural henna pastes containing only henna powder, a liquid (water, lemon juice, etc.) and an essential oil (lavender, cajuput, tea tree etc.) are not "shelf stable," meaning they expire quickly, and cannot be left out on a shelf for over one week without losing their ability to stain the skin.

The leaf of the henna plant contains a finite amount of lawsone. As a result, once the powder has been mixed into a paste, this leaching of dye molecule into the mixture will only occur for an average of two to six days. If a paste will not be used within the first few days after mixing, it can be frozen for up to four months to halt the dye release, for thawing and use at a later time. Commercially packaged pastes that remain able to stain the skin longer than seven days without refrigeration or freezing contain other chemicals besides henna that may be dangerous to the skin. After the initial seven-day release of lawsone dye, the henna leaf is spent, therefore any dye created by these commercial cones on the skin after this time period is actually the result of other compounds in the product. These chemicals are often undisclosed on packaging, and have a wide range of colors including what appears to be a natural looking color stain produced by dyes such as sodium picramate. These products often do not contain any henna. There are many adulterated henna pastes such as these, and others, for sale today that are erroneously marketed as "natural", "pure", or "organic", all containing potentially dangerous undisclosed additives. The length of time a pre-manufactured paste takes to arrive in the hands of consumers is typically longer than the seven-day dye release window of henna, therefore one can reasonably expect that any pre-made mass-produced cone that is not shipped frozen is a potentially harmful adulterated chemical variety. ·

Henna only stains the skin one color, a variation of reddish brown, at full maturity three days after application.

Powdered fresh henna, unlike pre-mixed paste, can be easily shipped all over the world and stored for many years in a well-sealed package.

Body art quality henna is often more finely sifted than henna powders for hair.

History

In Ancient Egypt, Ahmose-Henuttamehu (17th Dynasty, 1574 BCE) was probably a daughter of Seqenenre Tao and Ahmose Inhapy. Smith reports that the mummy of Henuttamehu's own hair had been dyed a bright red at the sides, probably with henna.[6]

In Europe, henna was popular among women connected to the aesthetic movement and the Pre-Raphaelite artists of England in the 1800s. Dante Gabriel Rossetti's wife and muse, Elizabeth Siddal, had naturally bright red hair. Contrary to the cultural tradition in Britain that considered red hair unattractive, the Pre-Raphaelites fetishized red hair. Siddal was portrayed by Rossetti in many paintings that emphasized her flowing red hair.[7] The other Pre-Raphaelites, including Evelyn De Morgan and Frederick Sandys, academic classicists such as Frederic Leighton, and French painters such as Gaston Bussière and the Impressionists, further popularized the association of henna-dyed hair and young bohemian women.

Opera singer Adelina Patti is sometimes credited with popularizing the use of henna in Europe in the late nineteenth century. Parisian courtesan Cora Pearl was often referred to as La Lune Rousse (the red-haired moon) for dying her hair red. In her memoirs, she relates an incident when she dyed her pet dog's fur to match her own hair.[8] By the 1950s, Lucille Ball popularized "henna rinse" as her character, Lucy Ricardo, called it on the television show I Love Lucy. It gained popularity among young people in the 1960s through growing interest in Eastern cultures.[9]

Muslim men may use henna as a dye for hair and most particularly their beards. This is considered sunnah, a commendable tradition of the Prophet Muhammad. Furthermore, a hadith (narration of the Prophet) holds that he encouraged Muslim women to dye their nails with henna to demonstrate femininity and distinguish their hands from those of men. Thus, some Muslim women in the Middle East apply henna to their finger and toenails as well as their hands.

Today

Commercially packaged henna, intended for use as a cosmetic hair dye, originated in ancient Egypt and the ancient Near East and is now popular in many countries in South Asia, Europe, Australia, and North America. The color that results from dyeing with henna depends on the original color of the hair, as well as the quality of the henna, and can range from orange to auburn to burgundy. Henna can be mixed with other natural hair dyes, including Cassia obovata for lighter shades of red or even blond and indigo to achieve brown and black shades. Some products sold as "henna" include these other natural dyes. Others may include metal salts that can interact with other chemical treatments, or oils and waxes that may inhibit the dye, or dyes which may be allergens.

Apart from its use as a hair dye, henna has recently been used as a temporal substitute to eyebrow pencil or even as eyebrow embroidery.[10]

Traditions of henna as body art

The different words for henna in ancient languages imply that it had more than one point of discovery and origin, as well as different pathways of daily and ceremonial use.

It is important to note that the modern term "Henna tattoo" is a marketing term only. Henna does not tattoo the skin and is not considered tattooing.

Henna has been used to adorn young women's bodies as part of social and holiday celebrations since the late Bronze Age in the Eastern Mediterranean. The earliest text mentioning henna in the context of marriage and fertility celebrations comes from the Ugaritic legend of Baal and Anath,[11] which has references to women marking themselves with henna in preparation to meet their husbands, and Anath adorning herself with henna to celebrate a victory over the enemies of Baal. Wall paintings excavated at Akrotiri (dating prior to the eruption of Thera in 1680 BCE) show women with markings consistent with henna on their nails, palms and soles, in a tableau consistent with the henna bridal description from Ugarit.[12] Many statuettes of young women dating between 1500 and 500 BCE along the Mediterranean coastline have raised hands with markings consistent with henna. This early connection between young, fertile women and henna seems to be the origin of the Night of the Henna, which is now celebrated in all the middle east.

The Night of the Henna was celebrated by most groups in the areas where henna grew naturally: Jews,[13] Muslims,[14] Sikhs, Hindus and Zoroastrians, among others, all celebrated marriages and weddings by adorning the bride, and often the groom, with henna.

Across the henna-growing region, Purim,[13] Eid,[15] Diwali,[16] Karva Chauth, Passover, Nowruz, Mawlid, and most saints' days were celebrated with some henna. Favorite horses, donkeys, and salukis had their hooves, paws, and tails hennaed. Battle victories, births, circumcision, birthdays, Zār, as well as weddings, usually included some henna as part of the celebration. Bridal henna nights remain an important custom in many of these areas, particularly among traditional families.

Henna was regarded as having Barakah ("blessings"), and was applied for luck as well as joy and beauty.[17] Brides typically had the most henna, and the most complex patterns, to support their greatest joy and wishes for luck. Some bridal traditions were very complex, such as those in Yemen, where the Jewish bridal henna process took four or five days to complete, with multiple applications and resist work.

The fashion of "Bridal Mehndi" in North Indian, Bangladesh, Northern Libya and in Pakistan is currently growing in complexity and elaboration, with new innovations in glitter, gilding, and fine-line work. Recent technological innovations in grinding, sifting, temperature control, and packaging henna, as well as government encouragement for henna cultivation, have improved dye content and artistic potential for henna.

Though traditional henna artists were from the Nai caste in India, and barbering castes in other countries (lower social classes), talented contemporary henna artists can command high fees for their work. Women in countries where women are discouraged from working outside the home can find socially acceptable, lucrative work doing henna.[18] Morocco, Mauritania,[19] Yemen, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, the United Arab Emirates, India and many other countries have thriving women's henna businesses. These businesses are often open all night for Eid, Diwali and Karva Chauth. Many women may work together during a large wedding, wherein hundreds of guests have henna applied to their body parts. This particular event at a marriage is known as the Mehndi Celebration or Mehndi Night, and is mainly held for the bride and groom.

Algeria

In Algeria, brides receive gifts of jewelry and have henna painted on their hands prior to their weddings.[20]

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, henna is also known as "kheena". Afghan tradition holds that henna brings good luck and happiness.[21] It is used by both men and women on many occasions such as wedding nights, Nawroz, Eidul fitr, Eidul Adha, Shabe-e Barat, and circumcision celebrations.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, women use mehndi on hands on occasions like weddings and engagements as well as during Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha and other events.[22] In wedding ceremonies, the Mehndi ceremony has traditionally been separated into two events; one organized by the bride's family, and one by the groom's family. These two events are solely dedicated for adorning the bride and groom in Mehndi and is known as a 'Mehndi Shondha' meaning the Evening of Mehndi.

Some brides tend to go for Alta. Sometimes Hindu women also apply Mehendi instead (or along with) Alta on their feet during the Bodhu Boron ceremony.

Bulgaria

In an attempt to ritually clean a bride before her wedding day, Bulgarian Romani decorate the bride with a blot of henna.[21] This blot symbolizes the drop of blood on the couples' sheets after consummating the marriage and breaking the female's hymen.[21] The tradition also holds that the longer the henna lasts, the longer the husband will love his new bride.[21]

Egypt

In Egypt, the bride gathers with her friends the night before her wedding day to celebrate the henna night.[21]

India

In India, Hindu women have motifs and tattoos on hands and feet on occasions like weddings and engagements. In Kerala, women and girls, especially brides, have their hands decorated with Mailanchi. In North Indian wedding ceremonies, there is one evening solely dedicated for adorning the bride and groom in Mehndi, also known as 'Mehndi ki raat.

Iran

In Iran, the most common use of henna is among the long wedding rituals practiced in Iran. The henna ritual, which is called ḥanā-bandān, is held for both the bride and the bridegroom during the wedding week[23] The ceremony is held prior to the wedding and is a traditional farewell ritual for newlyweds before they officially start their life together in a new house.[23] The ceremonies take place in the presence of family members, friends, relatives, neighbors, and guests.[23]

In Iran, Māzār (Persian: مازار) is indicating a job title for a person whose work is associated with the milling or grinding henna leaves and sell it in a powder form. This type of business is an old job still alive in some parts of Iran, especially in the world recognized archeologically ancient "Yazd" province.[24] The most famous one is a family owned business by "Mazar Atabaki" families resided in the land hundreds of years ago. Māzāri (Persian: مازاری) is a place for milling henna mixed with other herbs.

Israel & Palestine

In historical Palestine, now in Israel and territories of the Palestinian National Authority, some Middle Eastern and North African Jewish communities and families, also Druze, Christian and Muslim ones, host henna parties the night or week before a wedding, according to familial customs.[25] The use of henna in this region can be traced as far back to the Song of Songs in which the author wrote, "My beloved is to me a cluster of henna blossoms in the vineyards of Engedi."[26] Sephardic Jews and Mizrahi Jews, such as Moroccan Jews and Yemenite Jews who have immigrated to Israel, continue these familial customs.[27]

Malaysia

In Malaysia, henna (Malay: inai) is used to adorn the bride and groom's hands before the wedding at a berinai ceremony.[28]

Morocco

In Morocco, henna is applied symbolically when individuals go through life cycle events.[29] Moroccans refer to the paste as henna and the designs as naqsh, which means painting or inscription.[29] In Morocco, there are two types of henna artists: non-specialists, who traditionally partake in wedding rituals, and specialists, who partake in tourism and decorative henna.[29] Nqaasha, the low-end Henna specialists, are known for attracting tourists, which they refer to as gazelles or international tourists, in artisan slang.[29]

For Moroccans, a wedding festival can last up to 5 days, with 2 days involving henna art.[29] One of these days is referred to as azmomeg (meaning unknown), and is the Thursday before the wedding where guests are invited to apply henna to the bride.[29] The other henna ceremony occurs after the wedding ceremony, called the Day of Henna.[29] On this day, typically an older woman applies henna to the bride after she dips in the mikveh to ward off evil spirits who may be jealous of the newlyweds.[29] The groom is also painted with henna after the wedding.[29] During the groom's henna painting, he commonly wears black clothing, this tradition emerged from the Pact of Umar as the Jews were not permitted to dress similar to colorful Muslim dress in Morocco.[29]

Pakistan

In Pakistan, henna is often used in weddings, Eid ul fitr, Eidul Adha, milad and other events.[30] The henna ceremony is known as the Rasm-e-Heena, which is often one of the most important pre-wedding ceremonies celebrated by both the bride and groom's families. The night of mehndi, as the gathering at which the application of the henna is performed, usually falls on the second day of the festivities and one day before the wedding itself. The process commonly involves only the bride and groom but also can include close friends or other family members. The hands of the wedding couple are elegantly painted on this night to act as a sign of their union.

Somalia

In Somalia, henna has been used for centuries, it is cultivated from the leaves of the Ellan tree, which grows wild in the mountainous regions of Somalia. It is used for practical purposes such as dying hair and also more extravagantly by coloring the fingers and toes of married women and creating intricate designs.[31] It is also applied to the hands and feet of young Somali women in preparation for their weddings and all the Islamic celebrations. Sometimes also done by young school girls for several occasions [31]

Spain

Henna was cultivated in the Nasrid kingdom of Granada and applied to the face and hair by both sexes. After the Castilian conquest of Granada (1492), it was forbidden for Moriscos as it was a sign distinguishing them from Old Christians. After the expulsion of the Moriscos (1609-1614), cultivation ceased.[32]

Sudan

In Sudan, Henna dyes are regarded with a special sanctity in Sudan and for that reason they are always present during happy occasions: weddings and children circumcisions, in particular.

Henna has been part of Sudan's social and cultural heritage ever since the days of Sudan's ancient civilizations where both would-be couples get their hands and feet pigmented with this natural dye.

Children also have their hands and feet dyed with henna during their circumcision festivity.

Tunisia

In Tunisia, The traditional wedding process begins 8 days before the wedding ceremony when a basket is delivered to the bride, which contains henna.[33] The mother of the groom supervises the process in order to ensure all is being done correctly.[34] Today, the groom accompanies the bride in the ritual at the henna party, but the majority of henna painting is done on the bride's body.[33]

Turkey

During the Victorian era, Turkey was a major exporter of henna for use in dying hair.[35] Henna parties were commonly practiced in Turkey similarly to Arab countries.[36]

Yemen

For Yemenite Jews, most of them living in Israel, the purpose of a henna party is to ward off evil from the couple before their wedding.[37] In some areas, the party has evolved from tradition to an opportunity for the family to show off their wealth in the dressing of the bride.[37] For other communities, it is practiced as a ritual that has been passed on for generations.[37] The dressing of the bride is typically done by a post-menopausal woman in the bride's family.[37] Often, the dresser of the bride sings to the bride as she is dressed in exquisite designs.[37] These songs discuss marriage, what married life is like, and address the feelings a bride may have before her wedding.[37] The costumes worn by Yemenite brides to their henna parties is considered some of the most exquisite attire in the Yemenite community.[37] These outfits include robes, headwear, and often several pounds of silver jewelry.[37] This jewelry often holds fresh green herbs to ward off the Jinn in keeping with the ritual element of the party.[37]

The zavfa is the procession of the bride from her mother's house to the Henna Party.[37] During the zavfa, the guests of the party sing traditional songs to the bride and bang on tin plates and drums to ward off evil.[37] Today, it is common for the groom to join in on this aspect of the ritual, although traditionally it was only for the bride.[37] During the party, guests eat, sing, and dance.[37] Initially, the singing and dancing was to ward off the Jinn with loud noises, but today these elements are associated with the mitzvah of entertaining the bride and groom on their wedding day.[37]

In the middle of the party, the bride returns to her home to be painted in henna mixed by her mother.[37] The mixture consists of rose water, eggs, cognac, salt, and shadab, believed to be a magical herb that repels evil.[37] The bride changes into a less elaborate outfit and incense is burned while she is painted with henna.[37] Then, another zavfa (procession) occurs as the bride returns to her party.[37]

Back at the henna party, the bride sits on stage while family members and friends come up to her to have their palms marked with blots of henna.[37] These marks represent the long-lasting marriage as henna remains for many days.[37] It also represents the blood from breaking the hymen upon consummating the marriage on the wedding night.[37] Others add that the red stain on the hands of the guests is to mislead the evil spirits of the Jinn who are looking for the bride.[37] After the painting, the party ends after lasting about 4 or 5 hours.[37]

Health effects

Henna is known to be dangerous to people with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD deficiency), which is more common in males than females. Infants and children of particular ethnic groups, mainly from the Middle East and North Africa, are especially vulnerable.[38]

Though user accounts cite few other negative effects of natural henna paste, save for occasional mild allergic reactions (often associated with lemon juice or essential oils in a paste and not the henna itself), pre-mixed commercial henna body art pastes may have undisclosed ingredients added to darken stain, or to alter stain color. The health risks involved in pre-mixed paste can be significant. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does consider these risks to be adulterants and therefore illegal for use on skin.[39] Some commercial pastes have been noted to include: p-Phenylenediamine, sodium picramate, amaranth (red dye #2 banned in the US in 1976), silver nitrate, carmine, pyrogallol, disperse orange dye, and chromium.[40] These have been found to cause allergic reactions, chronic inflammatory reactions, or late-onset allergic reactions to hairdressing products and textile dyes.[41][42]

Regulation

The U.S. FDA has not approved henna for direct application to the skin. It is, however, grandfathered in as a hair dye and can only be imported for that purpose.[39][43] Henna imported into the U.S. that appears to be for use as body art is subject to seizure,[44] but prosecution is rare. Commercial henna products that are adulterated often claim to be 100% natural on product packaging in order to pass import regulations in other countries.

Varieties

Natural henna

Natural henna produces a rich red-brown stain which can darken in the days after it is first applied and last for several weeks. It is sometimes referred to as "red henna" to differentiate it from products sold as "black henna" or "neutral henna," which may not actually contain henna, but are instead made from other plants or dyes.[38][45]

Neutral henna

Neutral henna does not change the color of hair. This is not henna powder; it is usually the powder of the plant Senna italica (often referred to by the synonym Cassia obovata) or closely related Cassia and Senna species.

Black henna

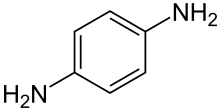

Black henna powder may be derived from indigo (from the plant Indigofera tinctoria). It may also contain unlisted dyes and chemicals[46] such as para-phenylenediamine (PPD), which can stain skin black quickly, but can cause severe allergic reactions and permanent scarring if left on for more than 2–3 days. The FDA specifically forbids PPD to be used for this purpose, and may prosecute those who produce black henna.[47] Artists who injure clients with black henna in the U.S. may be sued for damages.[48]

The name arose from imports of plant-based hair dyes into the West in the late 19th century. Partly fermented, dried indigo was called black henna because it could be used in combination with henna to dye hair black. This gave rise to the belief that there was such a thing as black henna which could dye skin black. Indigo will not dye skin black. Pictures of indigenous people with black body art (either alkalized henna or from some other source) also fed the belief that there was such a thing as black henna.

para-phenylenediamine

In the 1990s, henna artists in Africa, India, Bali, the Arabian Peninsula and the West began to experiment with PPD-based black hair dye, applying it as a thick paste as they would apply henna, in an effort to find something that would quickly make jet-black temporary body art. PPD can cause severe allergic reactions, with blistering, intense itching, permanent scarring, and permanent chemical sensitivities.[49][50] Estimates of allergic reactions range between 3% and 15%. Henna does not cause these injuries.[51] Black henna made with PPD can cause lifelong sensitization to coal tar derivatives while black henna made with gasoline, kerosene, lighter fluid, paint thinner, and benzene has been linked to adult acute leukemia.[52]

The most frequent serious health consequence of having a black henna temporary tattoo is sensitization to hair dye and related chemicals. If a person has had a black henna tattoo and later dyes their hair with chemical hair dye, the allergic reaction may be life-threatening and require hospitalization.[53] Because of the epidemic of PPD allergic reactions, chemical hair dye products now post warnings on the labels: "Temporary black henna tattoos may increase your risk of allergy. Do not colour your hair if: ... – you have experienced a reaction to a temporary black henna tattoo in the past."[54]

PPD is illegal for use on skin in western countries, though enforcement is difficult. Physicians have urged governments to legislate against black henna because of the frequency and severity of injuries, especially to children.[55] To assist the prosecution of vendors, government agencies encourage citizens to report injuries and illegal use of PPD black henna.[56][57] When used in hair dye, the PPD amount must be below 6%, and application instructions warn that the dye must not touch the scalp and must be quickly rinsed away. Black henna pastes have PPD percentages from 10% to 80%, and are left on the skin for half an hour.[40][58]

PPD black henna use is widespread, particularly in tourist areas.[59] Because the blistering reaction appears 3 to 12 days after the application, most tourists have left and do not return to show how much damage the artist has done. This permits the artists to continue injuring others, unaware they are causing severe injuries. The high-profit margins of black henna and the demand for body art that emulates "tribal tattoos" further encourage artists to deny the dangers.[60][61]

It is not difficult to recognize and avoid PPD black henna:[62]

- if a paste stains skin on the torso black in less than ½ hour, it has PPD in it.

- if the paste is mixed with peroxide, or if peroxide is wiped over the design to bring out the color, it has PPD in it.

Anyone who has an itching and blistering reaction to a black body stain should go to a doctor, and report that they have had an application of PPD to their skin.

PPD sensitivity is lifelong. A person who has become sensitized through black henna tattoos may have future allergic reactions to perfumes, printer ink, chemical hair dyes, textile dye, photographic developer, sunscreen and some medications. A person who has had a black henna tattoo should consult their physician about the health consequences of PPD sensitization.[63][45]

See also

References

- Bailey, L.H.; Bailey, E.Z. (1976). Hortus Third: A concise dictionary of plants cultivated in the United States and Canada. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0025054707.

- Cartwright-Jones, Catherine (2004). "Cassia Obovata". Henna for Hair. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Dennis, Brady (26 March 2013). "FDA: Beware of "black henna" tattoos". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- "Definition of HENNA". www.merriam-webster.com. 25 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- "Henna Powder of Prem Dulhan". Lia. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- G. Elliott Smith, The Royal Mummies, Duckworth Publishing; (September 2000)

- "Aesthetics". Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- Cora Pearl (1886). Mémoires de Cora Pearl. J. Lévy.

- Sherrow, Victoria (2006). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Greenwood. pp. 206–207. ISBN 978-0313331459.

- "You Can Now Tint Your Eyebrows With Henna". InStyle.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- de Moor, Johannes C. (1971). The seasonal pattern in the Ugaritic myth of Balu, according to the version of Ilimilku (Alter Orient und Altes Testament). Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker. ISBN 978-3-7887-0293-9. OCLC 201316.

- D̲oumas, Christos (1992). The wall-paintings of Thera. Athens: Thera Foundation. ISBN 978-960-220-274-6. OCLC 30069766.

- Brauer, Erich; Raphael Patai (1993). The Jews of Kurdistan. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2392-2. OCLC 27266639.

- Westermarck, Edward (1972) [1914]. Marriage ceremonies in Morocco. London: Curzon Press. ISBN 978-0-87471-089-2. OCLC 633323.

- Hammoudi, Abdellah (1993). The victim and its masks: an essay on sacrifice and masquerade in the Maghreb. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31525-6. OCLC 27265476.

- Saksena, Jogendra (1979). Art of Rajasthan: Henna and Floor Decorations. Delhi: Sundeep. OCLC 7219114.

- Westermarck, E. (1926). Ritual and Belief in Morocco Vols 1 & 2. London, UK: Macmillan and Company, Limited

- "Easy Mehndi Design Tutorial". 4 December 2014. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021.

- Tauzin, Aline (1998). Le henné, art des femmes de Mauritanie [Henna, the art of Mauritanian women] (in French). Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-203487-8.

- "Wedding Customs – Celebrating a Joyous Occasion." Algeria.com – Algeria Channel. Accessed 2 December 2018. http://www.algeria.com/wedding-customs/ .

- Monger, George. 2004. Marriage customs of the world: from henna to honeymoons. Santa Barbara Calif: ABC-CLIO.

- "The Bangladeshi Wedding Ceremony". Desiblitz. 11 June 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- http://www.iranicaonline.org "Encyclopædia Iranica." RSS. Accessed 24 March 2021. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/henna .

- "East meets West: the rise of henna". Lush Fresh Handmade Cosmetics UK. Archived from the original on 29 October 2018.

- Rosenhouse, Judith (1 January 2000). "A comparative study of women's wedding songs in colloquial Arabic". EDNA, Estudios de Dialectología Norteafricana y Andalusí. 5: 29–47. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- Song of Solomon 1:14

- Sharabi, Rachel (2006). "The Bride's Henna Ritual: Symbols, Meanings and Changes". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues. 11 (1): 11–42. doi:10.1353/nsh.2006.0014. JSTOR 40326803. S2CID 163092214. ProQuest 197740785.

- Our Malaysia: Multi-cultural Activity Book for Young Malaysians: Creative! Informative! Fun! Kuala Lumpur: Arpitha Associates, 2005.

- Spurles, Kelly; L, Patricia (2004). Henna for Brides and Gazelles: Ritual, Women's Work and Tourism in Morocco (Thesis). hdl:1866/14244. ISBN 978-0-612-97895-9. ProQuest 305053576.

- "A brief history of henna". The Express Tribune. 4 August 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- Akou, Heather Marie (2011). The Politics of Dress in Somali Culture. Indiana University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-253-22313-5.

- Caro Baroja, Julio (2000) [1976]. Los moriscos del Reino de Granada. Ensayo de historia social (in European Spanish) (5ª ed.). Madrid: Istmo. pp. 111–112. ISBN 84-7090-076-5.

- Schely-Newman, Esther (2002). Our Lives are But Stories: Narratives of Tunisian-Israeli Women. Wayne State University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8143-2876-7.

- Schely-Newman, Esther (2002). Our Lives are But Stories: Narratives of Tunisian-Israeli Women. Wayne State University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8143-2876-7.

- Sherrow, Victoria. Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006. 156.

- Dessing, Nathal M. (2001). Rituals of Birth, Circumcision, Marriage, and Death Among Muslims in the Netherlands. Peeters Publishers. p. 117. ISBN 978-90-429-1059-1.

- Buse, William (31 December 2015). "What becomes a bride the most: the Yemenite Jewish henna". Visual Ethnography. 4 (2). doi:10.12835/ve2015.2-0049.

- de Groot, Anton C. (July 2013). "Side-effects of henna and semi-permanent 'black henna' tattoos: a full review". Contact Dermatitis. 69 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1111/cod.12074. PMID 23782354. S2CID 140100016.

- "Temporary Tattoos & Henna/Mehndi". Food and Drug Administration. 3 March 2022.

- Kang, Ik-Joon; Lee, Mu-Hyoung (July 2006). "Quantification of para-phenylenediamine and heavy metals in henna dye". Contact Dermatitis. 55 (1): 26–29. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00845.x. PMID 16842550. S2CID 22176978.

- Dron, P; Lafourcade, MP; Leprince, F; Nonotte-Varly, C; Van Der Brempt, X; Banoun, L; Sullerot, I; This-Vaissette, C; Parisot, L; Moneret-Vautrin, DA (June 2007). "Allergies associated with body piercing and tattoos: a report of the Allergy Vigilance Network". European Annals of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 39 (6): 189–192. PMID 17713170. S2CID 7903601.

- Raupp, P; Hassan, JA; Varughese, M; Kristiansson, B (1 November 2001). "Henna causes life threatening haemolysis in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 85 (5): 411–412. doi:10.1136/adc.85.5.411. PMC 1718961. PMID 11668106.

- "§ 73.2190 Henna". Listing of Color Additives Exempt from Certification. Federal Register. 30 July 2009. Archived from the original on 5 November 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- "Accessdate.fda.gov". Accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- "Dangers of black henna". nhs.uk. 26 April 2018. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Singh, M.; Jindal, S. K.; Kavia, Z. D.; Jangid, B. L.; Khem Chand (2005). "Traditional Methods of Cultivation and Processing of Henna. Henna, Cultivation, Improvement and Trade". Henna: Cultivation, Improvement, and Trade. Jodhpur: Central Arid Zone Research Institute. pp. 21–24. OCLC 124036118.

- "FDA.gov". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- "Rosemariearnold.com". Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Van den Keybus, C.; Morren, M.-A.; Goossens, A. (September 2005). "Walking difficulties due to an allergic reaction to a temporary tattoo". Contact Dermatitis. 53 (3): 180–181. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.0407m.x. PMID 16128770. S2CID 28624688.

- Stante, M; Giorgini, S; Lotti, T (April 2006). "Allergic contact dermatitis from henna temporary tattoo". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 20 (4): 484–486. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01483.x. PMID 16643167. S2CID 43067542.

- Jung, Peter; Sesztak-Greinecker, Gabriele; Wantke, Felix; Gotz, Manfred; Jarisch, Reinhart; Hemmer, Wolfgang (April 2006). "A painful experience: black henna tattoo causing severe, bullous contact dermatitis". Contact Dermatitis. 54 (4): 219–220. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.0775g.x. PMID 16650103. S2CID 43613761.

- Hassan, Inaam Bashir; Islam, Sherief I. A. M.; Alizadeh, Hussain; Kristensen, Jorgen; Kambal, Amr; Sonday, Shanaaz; Bernseen, Roos M. D. (21 July 2009). "Acute leukemia among the adult population of United Arab Emirates: an epidemiological study". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 50 (7): 1138–1147. doi:10.1080/10428190902919184. PMID 19557635. S2CID 205701235.

- Sosted, Heidi; Johansen, Jeanne Duus; Andersen, Klaus Ejner; Menne, Torkil (February 2006). "Severe allergic hair dye reactions in 8 children". Contact Dermatitis. 54 (2): 87–91. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00746.x. PMID 16487280. S2CID 39281376.

- Commission Directive 2009/134/EC of 28 October 2009 amending Council Directive 76/768/EEC concerning cosmetic products for the purposes of adapting Annex III thereto to technical progress

- Jacob, Sharon E.; Zapolanski, Tamar; Chayavichitsilp, Pamela; Connelly, Elizabeth Alvarez; Eichenfield, Lawrence F. (1 August 2008). "p-Phenylenediamine in Black Henna Tattoos". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 162 (8): 790–2. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.8.790. PMID 18678815.

- "Black Henna". Florida Department of Health. 20 December 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- "Health Canada alerts Canadians not to use 'black henna' temporary tattoo ink and paste containing PPD" (Press release). Health Canada. 11 August 2003. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008.

- Avnstorp, Christian; Rastogi, Suresh C.; Menne, Torkil (August 2002). "Acute fingertip dermatitis from a temporary tattoo and quantitative chemical analysis of the product". Contact Dermatitis. 47 (2): 109–125. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470210_11.x. PMID 12455547. S2CID 34550567.

- Marcoux, Danielle; Couture‐Trudel, Pierre‐Marc; Riboulet‐Delmas, Gisèle; Sasseville, Denis (23 November 2002). "Sensitization to Para‐Phenylenediamine from a Streetside Temporary Tattoo". Pediatric Dermatology. 19 (6): 498–502. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00218.x. PMID 12437549. S2CID 23543707.

- Onder, M (July 2003). "Temporary holiday 'tattoos' may cause lifelong allergic contact dermatitis when henna is mixed with PPD". Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2 (3–4): 126–130. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00083.x. PMID 17163917. S2CID 38957088.

- Onder, Meltem; Atahan, Cigdem Asena; Oztas, Pinar; Oztas, Murat Orhan (September 2001). "Temporary henna tattoo reactions in children". International Journal of Dermatology. 40 (9): 577–579. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01248.x. PMID 11737452. S2CID 221816034.

- "PPD In 'Black Henna' Temporary Tattoos Is Not Safe". Health Canada. 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 24 April 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Moro, Paola; Morina, Marco; Milani, Fabrizia; Pandolfi, Marco; Guerriero, Francesca; Bernardo, Luca (11 July 2016). "Sensitization and Clinically Relevant Allergy to Hair Dyes and Clothes from Black Henna Tattoos: Do People Know the Risk? An Uncommon Serious Case and a Review of the Literature". Cosmetics. 3 (3): 23. doi:10.3390/cosmetics3030023. ISSN 2079-9284.

Further reading

- Badoni Semwal, Ruchi; Semwal, Deepak Kumar; Combrinck, Sandra; Cartwright-Jones, Catherine; Viljoen, Alvaro (August 2014). "Lawsonia inermis L. (henna): Ethnobotanical, phytochemical and pharmacological aspects". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 155 (1): 80–103. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.05.042. PMID 24886774.

.jpg.webp)