Black Hawk (Sauk leader)

Black Hawk, born Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak (Sauk: Mahkatêwe-meshi-kêhkêhkwa) (1767 – October 3, 1838), was a Sauk leader and warrior who lived in what is now the Midwestern United States. Although he had inherited an important historic sacred bundle from his father, he was not a hereditary civil chief. Black Hawk earned his status as a war chief or captain by his actions: leading raiding and war parties as a young man and then a band of Sauk warriors during the Black Hawk War of 1832.

Black Hawk | |

|---|---|

Portrait by George Catlin, 1832 | |

| Born | Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak 1767 |

| Died | October 3, 1838 (aged 70–71) Davis County, Iowa, U.S. |

| Monuments | Black Hawk Statue, Black Hawk State Historic Site |

| Nationality | Sauk |

| Other names | Black Sparrow Hawk |

| Occupation(s) | War captain; band leader |

| Known for | Black Hawk War |

During the War of 1812, Black Hawk fought on the side of the British against the US in the hope of pushing white American settlers away from Sauk territory. Later, he led a band of Sauk and Fox warriors, known as the British Band, against white settlers in Illinois and present-day Wisconsin during the 1832 Black Hawk War. After the war, he was captured by US forces and taken to the Eastern US, where he and other war leaders were taken on a tour of several cities.

Shortly before being released from custody, Black Hawk told his story to an interpreter. Aided also by a newspaper reporter, he published Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, or Black Hawk, Embracing the Traditions of his Nation... in 1833. The first Native American autobiography to be published in the US, his book became an immediate bestseller and has gone through several editions. Black Hawk died in 1838, at age 70 or 71, in what is now southeastern Iowa. He has been honored by an enduring legacy: his book, many eponyms, and other tributes.

Early life

Black Hawk, or Black Sparrow Hawk (Sauk Ma-kat-tai-me-she-kia-kiak [Mahkate:wi-meši-ke:hke:hkwa], "be a large black hawk")[1] was born in 1767 in the village of Saukenuk on the Rock River (present-day Rock Island, Illinois).[2]: p.13 Black Hawk's father Pyesa was the tribal medicine man of the Sauk people.[3]

Little is known about Black Hawk's youth. He was said to be a descendant of Nanamakee (Thunder), a Sauk chief who, according to tradition, met an early French explorer, possibly Samuel de Champlain.[4]: p.4, p.12 At about age 15, Black Hawk distinguished himself by wounding an enemy and was placed in the ranks of the braves. Shortly after this Black Hawk accompanied his father Pyesa on a raid against the Osage. He won approval by killing and scalping his first enemy.[2]: pp.19-20 [4]: p.14 The young Black Hawk tried to establish himself as a war captain by leading other raids. He had limited success until, at about age 19, he led 200 men in a battle against the Osage, in which he personally killed five men and one woman.[2]: p.21 [4]: p.16 Soon after, he joined his father in a raid against Cherokee along the Meramec River in Missouri. After Pyesa died from wounds received in the battle, Black Hawk inherited the Sauk sacred bundle which his father had carried, giving him an important role in the tribe.[4]: pp. 16–17

War leader

After an extended period of mourning for his father, Black Hawk resumed leading raiding parties over the next years, usually targeting the traditional enemy, the Osage. Black Hawk did not belong to a clan that provided the Sauk with hereditary civil leaders, or "chiefs." He achieved status through his exploits as a warrior and by leading successful raiding parties. Men like Black Hawk are sometimes called "war chiefs," but historian Patrick Jung writes, "It is more accurate to call them 'war leaders' since the nature of their office and the power that it wielded was much different from that of a civil chief."[5] Twenty-first-century historians such as John W. Hall have suggested the term "war captain" for this role.[6]

War of 1812

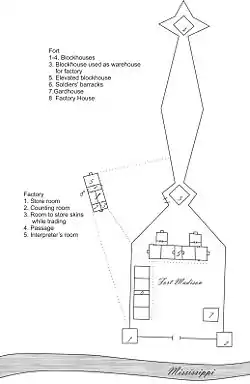

During the War of 1812, Black Hawk, now 45, served as a war leader of a Sauk band at their village of Saukenuk, which fielded about 200 warriors. He supported the invalidity of Quashquame's Treaty of St. Louis (1804) between the Sauk and Fox nations and then-governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory that ceded territory, including Saukenuk, to the United States.[7] The Sauk and Fox are consensus-based decision makers and those representatives sent to the meeting with the US government did not have the power to cede tribal territory, although Quashquame did. The lack of the consensus aspect by each of the Sauk and Fox councils meant that the treaty could never be considered valid by Black Hawk and other traditionalists.[8] Black Hawk took part in skirmishes against US forces at the newly constructed Fort Madison in the disputed land; this was the first time he fought directly against the U.S. Army.[9]

During the War of 1812, the forces of Great Britain and its colonies in present-day Canada were engaged against those of the U.S., with major battles on the Great Lakes and surrounding remote lands. The British depended upon alliances with the Native American population to wage war in this area since the British were occupied with Napoleon in Europe. Robert Dickson, a Scottish fur trader, amassed a sizable force of Native Americans at Green Bay to assist the British in operations around the Great Lakes. Most were from the Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Kickapoo, and Ottawa tribes. Black Hawk and his band of about 200 Sauk warriors were included in this group of allies.

Dickson commissioned Black Hawk at the rank of brevet brigadier general,[7] with command over all native allies at Green Bay, and presented him with a silk flag, a medal, and a written certificate of good behavior and alliance with the British. The war leader preserved the certificate for 20 years; it was found by U.S. forces after the Battle of Bad Axe, along with a flag similar in description to that which Dickson gave to Black Hawk.[7]

During the war, Black Hawk and Native warriors fought in several engagements alongside Major-General Henry Procter on the borders of Lake Erie.[8] Black Hawk was at the Battle of Frenchtown, Fort Meigs, and the attack on Fort Stephenson.[10][11] The United States Army was able to inflict a significant defeat on Tecumseh's Confederacy by killing Tecumseh during the war.

Black Hawk despaired over the many killed in the fighting; soon after, he quit the war to return home. Back in Saukenuk, he found that his rival, Keokuk, had become the tribe's war chief.[7] Black Hawk rejoined the British effort toward the end of the war, fighting alongside British forces in campaigns along the Mississippi River near the Illinois Territory.[10] At the Battle of Credit Island, and by harassing U.S. troops at Fort Johnson, Black Hawk helped the British to push the Americans out of the upper Mississippi River valley.[12]

Black Hawk fought in the Battle of the Sink Hole (May 1815), leading an ambush on a group of Missouri Rangers. Conflicting accounts of the action were given by the Missouri leader John Shaw[13] and by Black Hawk.[14]

After the end of the War of 1812, Black Hawk signed a peace treaty in May 1816 that re-affirmed the treaty of 1804. Later he said he was not aware of this stipulation.[8]

Black Hawk War

As a consequence of the 1804 treaty, the American government believed that the Sauk and Fox tribes had ceded their lands in Illinois and in 1828 were moved west of the Mississippi River. Black Hawk and other tribal members disputed the treaty, as noted above, and said leaders had signed it without full tribal authorization.[15] Angered by the loss of his birthplace, between 1830 and 1831 Black Hawk led a number of incursions across the Mississippi to Illinois. He was persuaded to return west each time without bloodshed.

In April 1832, encouraged by promises of alliance with other tribes and with Britain, he moved his so-called "British Band" of more than 1500 people, both warriors and non-combatants, into Illinois.[15] Finding no allies, he tried to return to Iowa, but the undisciplined Illinois militia provoked open attack at the Battle of Stillman's Run.[16] A number of other violent engagements followed. The governors of Michigan Territory and Illinois mobilized their militias to hunt down Black Hawk's Band. These actions led to the last Native American War fought on the east side of the Mississippi River.[17] The conflict became known as the Black Hawk War.

When Black Hawk entered Illinois in April, his British Band was composed of about 500 warriors and 1,000 old men, women, and children.[18][19] The group included members of the Sauk, Fox and Kickapoo tribes. They crossed the river near the mouth of the Iowa River and followed the Rock River northeast. Along the way, they passed the ruins of Saukenuk and headed for the village of Ho-Chunk prophet White Cloud.[20]

As the war progressed, factions of other tribes joined, or tried to join Black Hawk. Other Native Americans and settlers carried out acts of violence for personal reasons amidst the chaos of the war.[21][22] In one example, a band of hostile Ho-Chunk intent on joining Black Hawk's Band attacked and killed the party of Felix St. Vrain in what Americans knew as the St. Vrain massacre.[23] This act was an exception as most Ho-Chunk sided with the U.S. during the Black Hawk War; the warriors who attacked St. Vrain's party had acted independently of the Ho-Chunk nation.[23] From April to August, Potawatomi warriors also joined with Black Hawk's Band.[24]

The war stretched from April to August 1832, with a number of battles, skirmishes and massacres on both sides. Black Hawk led his men in another conflict, the Battle of Wisconsin Heights. Afterward, the Illinois and Michigan Territory militias caught up with Black Hawk's "British Band" for the final confrontation at Bad Axe. At the mouth of the Bad Axe River, pursuing soldiers, their Indian allies, and a U.S. gunboat killed hundreds of Sauk and Potawatomi men, women and children.[25] On August 27, 1832, Black Hawk and Wabokieshiek asked to surrender to the Indian agent Joseph Street but were instead taken to Zachary Taylor. They surrendered to Lieutenant Jefferson Davis, future president of the Confederacy, after hiding on an unnamed island in the Mississippi River.[26][27][28][29]

Tour of the East

Following the war, with most of the British Band killed and the rest captured or disbanded, the defeated Black Hawk was held in captivity at Jefferson Barracks near Saint Louis, Missouri together with Neapope, White Cloud, and eight other leaders.[24] After eight months, in April 1833 they were taken east, as ordered by U.S. President Andrew Jackson. The men were taken by steamboat, carriage, and railroad, and met with large crowds wherever they went. Jackson wanted them to be impressed with the power of the United States. Once in Washington, D.C., they met with Jackson and Secretary of War Lewis Cass. Afterward, they were delivered to their final destination, prison at Fortress Monroe in Hampton, Virginia.[24] They were held only a few weeks at the prison, during which they posed for portraits by different artists.

On June 5, 1833, the men were sent west by steamboat on a circuitous route that took them through many large cities. Again, the men were a spectacle everywhere they went, and were greeted by huge crowds of people in cities such as Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York,.[24] In the west, closer to the battle sites and history of conflict, the reception was much different. For instance, in Detroit, a crowd burned and hanged effigies of the prisoners.[24]

Early autobiography by Native American

Near the end of his captivity in 1833, Black Hawk told his life story to Antoine LeClaire, a government interpreter. Edited by the local reporter J.B. Patterson, Black Hawk's account was one of the first Native American autobiographies published in the U.S.[30] [2][10] The book immediately became a best seller and has gone through numerous editions.[10] In its time, it was not without controversy. Thomas Ford, governor of Illinois, disliked Black Hawk, Le Claire, and George Davenport, and believed that Black Hawk had little to do with the writing of his autobiography, dismissing the book as a "catch-penny publication."[31]

Assessment as Sauk leader

Although not a hereditary chief, Black Hawk filled a leadership void within the Sauk community. When Quashquame ceded much of the Sauk homeland in 1804 to the United States, including the main village Saukenuk, he was viewed as ineffective. Black Hawk wrote in his autobiography:

It subsequently appeared that they had been drunk the greater part of the time while at St. Louis. This was all myself and nation knew of the treaty of 1804. It has since been explained to me. I found by that treaty, that all of the country east of the Mississippi, and south of Jeffreon was ceded to the United States for one thousand dollars a year. I will leave it to the people of the United States to say whether our nation was properly represented in this treaty? Or whether we received a fair compensation for the extent of country ceded by these four individuals? I could say much more respecting this treaty, but I will not at this time. It has been the origin of all our serious difficulties with the whites.[2]

Because of his role in the disputed 1804 treaty, the tribe reduced its support of Quashquame and made him a minor chief. "Quasquawma, was chief of this tribe once, but being cheated out of the mineral country, as the Indians allege, he was denigrated from his rank and his son-in-law Taimah elected in his stead."[32] Although Quashquame and Black Hawk were at odds, the younger man did not directly challenge the civil chief. They apparently remained on good terms as Black Hawk rose in importance and Quashquame faded. Quashquame avoided confrontation with the U.S., while Black Hawk did not. After Black Hawk led an aborted takeover of Fort Madison in the Spring of 1809, Quashquame worked to restore relations with the US Army the next day.[33]

Quashquame told Gen. William Clark during a meeting in 1810 or 1811:

My father, I left my home to see my great-grandfather, the president of the United States, but as I cannot proceed to see him, I give you my hand as to himself. I have no father to whom I have paid any attention but yourself. If you hear anything, I hope that you will let me know, and I will do the same. I have been advised several times to raise the tomahawk. Since the last war we have looked upon the Americans as friends, and I shall hold you fast by the hand. The Great Spirit has not put us on the earth to war with the whites. We have never struck a white man. If we go to war it is with the red flesh. Other nations send belts among us, and urge us to war. They say that if we do not, the Americans will encroach upon us, and drive us off our lands.[34]

During the run up to the War of 1812, the US viewed Quashquame as loyal, or at least neutral. They knew Black Hawk led those Sauk warriors allied with the British. Quashquame led all Sauk non-combatants during the war, and they retreated to Saint Louis. Black Hawk thought this was an ideal arrangement:

... all the children and old men and women belonging to the warriors who had joined the British were left with them to provide for. A council had been called which agreed that Quashquame, the Lance, and other chiefs, with the old men, women and children, and such others as chose to accompany them, should descend the Mississippi to St. Louis, and place themselves under the American chief stationed there. They accordingly went down to St. Louis, were received as the friendly band of our nation, were sent up the Missouri and provided for, while their friends were assisting the British![2]

A rift developed among the Sauk after the war. In 1815 Quashquame was part of a large delegation who signed a treaty confirming a split between the Sauk along the Missouri River and the Sauk who lived along the Rock River at Saukenuk.[35] The Rock River group of Sauk was commonly known as the British Band; their warriors were the core of those Sauk who participated in the Black Hawk War. About 1824, Quashquame sold a large Sauk village in Illinois to a trader Captain James White. White gave Quashquame "a little 'sku-ti-apo' [liquor] and two thousand bushels of corn" for the land, which later was developed as Nauvoo, Illinois.[36] This land sale likely aggravated Black Hawk and other Sauk who wanted to maintain their claim on Illinois.

As Quashquame was eclipsed by his son-in-law Taimah as the Sauk chief favored by the U.S., his compromise position lost standing compared to Black Hawk's resistance. When Caleb Atwater wrote about his visit to Quashquame in 1829, he depicted the leader as feeble, more interested in art and leisure than politics, but still advocating diplomacy over conflict.[37] In the summer of 1830, Black Hawk began his incursions into the disputed territory of Illinois, which eventually leading to the Black Hawk War.

Black Hawk's frequent rival was Keokuk, a Sauk war chief held in high esteem by the U.S. government. Officials believed that he was calm and reasonable, willing to negotiate, unlike Black Hawk. Black Hawk despised Keokuk, and viewed him as cowardly and self-serving, at one point threatening to kill him for not defending Saukenuk.[38] After the Black Hawk War, US officials designated Keokuk as the main Sauk leader and would only deal with him.

Last days

After his tour of the east, Black Hawk lived with the Sauk along the Iowa River and later the Des Moines River near Iowaville[39] in what is now southeast Iowa. At the end of his life, he tried to reconcile both with American settlers and with his Sauk rivals, including Keokuk. He spent some time in Burlington, Iowa in the home of businessman and legislator Jeremiah Smith, Jr. An attorney with whom he shared a room recalled, "I roomed with Black Hawk for weeks, and observed him carefully and under all circumstances. He was uniformly kind and polite, especially at the table; but often silent, abstracted and melancholy.... He presented the noble spectacle of a warrior chief, conquered and disgraced with his tribe by his conquerors; but, resigned to his fate and covered with the scars of many battles, in the spirit of true heroism, breaking bread with and enjoying the hospitality of his destroyers."[40]

In an 1838 address at Fort M. Madison in the year of his death, he said the following:

It has pleased the Great Spirit that I am here today— I have eaten with my white friends. The earth is our mother— we are now on it, with the Great spirit above us; it is good. I hope we are all friends here. A few winters ago I was fighting against you. I did wrong, perhaps, but that is past—it is buried—let it be forgotten.

Rock River was a beautiful country. I liked my towns, my cornfields and the home of my people. I fought for it. It is now yours. Keep it as we did— it will produce you good crops.

I thank the Great Spirit that I am now friendly with my white brethren. We are here together, we have eaten together; we are friends; it is his wish and mine. I thank you for your friendship.

I was once a great warrior; I am now poor. Keokuk has been the cause of my present situation; but I do not attach blame to him. I am now old. I have looked upon the Mississippi since I have been a child. I love the great river. I have dwelt upon its banks from the time I was an infant. I look upon it now. I shake hands with you, and as it is my wish, I hope you are my friends.

— --Address by Black Hawk, July 4, 1838, at Fort Madison.[41]

Black Hawk died on October 3, 1838, after two weeks of illness. He was buried on the farm of his friend James Jordan, on the north bank of the Des Moines River in Davis County.

In July 1839, his remains were stolen by James Turner, who prepared his skeleton for exhibition. Black Hawk's sons Nashashuk and Gamesett went to Governor Robert Lucas of Iowa Territory, who used his influence to bring the bones to security in his offices in Burlington. With the permission of Black Hawk's sons, the remains were held by the Burlington Geological and Historical Society. When the Society's building burned down in 1855, Black Hawk's remains were destroyed.[42]

An alternative account is that Governor Lucas passed Black Hawk's bones to Enos Lowe, a Burlington physician, who was said to have left them to his partner, Dr. McLaurens. After McLaurens moved to California, workers were reported to have found the bones at his house. They buried the remains in a potter's grave in Aspen Grove Cemetery in Burlington.[43]

There is a marker for him[44] in the Iowaville Cemetery on the hill over the river, although it is unknown if any of his remains are there.

Personal life

Black Hawk's wife was known as As-she-we-qua[45] (died August 28, 1846),[46] or Singing Bird (her English name was Sarah Baker) with whom he had five children. His oldest son and youngest daughter died in the same year, before 1820, and he mourned their passing following Sauk tradition for two years.[45] According to Sauk tradition, Black Hawk spent these two years of his life mourning the loss of his children by living alone and fasting.[47] His other children were a daughter Namequa (Running Fawn, Ailey Baker was her English name) and his sons Nasheakusk (aka Nashashuk) and Gamesett (aka Nasomsee).[46][48]

Legacy

Through interpreter Antoine LeClair, Black Hawk dictated an autobiography titled Life of Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak (or, Life of Black Hawk), originally published in 1833.[14][49]

A sculpture by Lorado Taft overlooks the Rock River in Oregon, Illinois. Entitled The Eternal Indian, this statue is commonly known as the Black Hawk Statue.[50] In modern times Black Hawk is considered a tragic hero and numerous commemorations exist.[10] These are mostly in the form of eponyms; many roads, sports teams and schools are named after Black Hawk. Among the numerous wars in United States history, however; the Black Hawk War is one of few named for a person.[51]

According to a widespread myth, the Olympic gold medal-winning athlete Jim Thorpe was said to be descended from Black Hawk.[52]

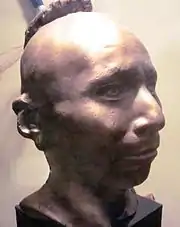

The Wisconsin born African American spiritualist and trance medium Leafy Anderson claimed that Black Hawk was one of her major spirit guides. This spirit's guidance and protection are sought by the members of many churches within the loosely allied Spiritual Church Movement which she founded.[53][54][55] Special "Black Hawk services" are held to invoke his assistance, and busts or statues representing him are kept on home and church altars by his devotees.[53]

Notable examples of eponyms

- Several place names, including Black Hawk County, Iowa, the Black Hawk Bridge between Iowa and Wisconsin, and the historical Black Hawk Purchase in Iowa.

- Four United States Navy vessels were named USS Black Hawk.

- The 2nd Squadron of the 1st US Cavalry Regiment (2-1 CAVALIER Urdu and the other side of the house are not related to the original

- One Liberty ship built in 1943 was named Black Hawk.

- The Chicago Blackhawks of the National Hockey League indirectly derive their name from Black Hawk. Their first owner, Frederic McLaughlin, was a commander with the 333rd Machine Gun Battalion of the 86th Infantry Division during World War I, nicknamed the "Black Hawk Division" after the war leader. McLaughlin named the hockey team in honor of his military unit.[56]

- The Atlanta Hawks were named the Tri-Cities Blackhawks in the inaugural season of the NBA in the Tri-Cities (now Quad Cities) area in Illinois and Iowa. The team was named for the Black Hawk War.[57]

- Iowa's state nickname (Hawkeye State) was originally adopted in 1838, paying tribute to Chief Black Hawk. The Iowa Hawkeyes, the athletic teams of the University of Iowa, take their nickname from the state’s.

- The Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk, a four-blade, twin-engine, medium-lift utility helicopter manufactured by Sikorsky Aircraft, used by the US military and many armed forces around the world.

- Blackhawk Middle School,[58] in Bensenville, Illinois

- Black Hawk College, a community college whose main campus is in Moline, IL.[59]

- Blackhawk Country Club, a private golf club in Shorewood Hills, Wisconsin is named for Black Hawk.[60]

- The athletic teams of Prairie du Chien High School in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin are nicknamed the Blackhawks in his honor.[61]

- The athletic teams of Fort Atkinson High School, Wisconsin are named "Blackhawks" for Black Hawk.[62]

- The athletic teams of West Aurora High School, Illinois are named the Blackhawks for Black Hawk. Their mascot is also named "Chief Blackhawk".

- The film "Big Chief, Black Hawk", named after a Mardi Gras Indian Tribe, came from Terrance Williams Jr. naming his tribe "Black Hawk Hunters" in homage to Black Hawk.[63]

See also

References

- Bright, William (2004). Native American Place Names of the United States, Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 66.

- Black Hawk, Antoine LeClair (interpreter), and J.B. Patterson, ed. Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak or Black Hawk, Embracing the tradition of his nation--Indian wars in which he has been engaged--cause of joining the British in their late war with America, and its history--description of the Rock River village--manners and customs--encroachments by the whites, contrary to treaty--removal from his village in 1831. With an account of the cause and general history of the late war, his surrender and confinement at Jefferson Barracks, and travels through the United States. Boston: Russell, Odiorn & Metcalf, 1834. Retrieved: Dec 6, 2022.

- Stevens, Frank Everett (2000). "Black Hawk War, Part 02 – Black Hawk and His Times". myeducationresearch.org. The Pierian Press. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Roger L. Nichols, Black Hawk and the Warrior's Path (Arlington Heights, Illinois: Harlan Davidson, 1992; ISBN 0-88295-884-4).

- Jung, 55.

- See for example John W. Hall, Uncommon Defense: Indian Allies in the Black Hawk War (Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 2.

- Smith, William Rudolph. The History of Wisconsin: In Three Parts, Historical, Documentary, and Descriptive, ( Internet Archive), B. Brown: 1854, pp. 221–406. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- Lewis, James. ""Background: The Black Hawk War of 1832" Archived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Abraham Lincoln Digitization Project, Northern Illinois University. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- McKusick, Marshall B. (2009). "Fort Madison, 1808-1813". In William E. Whittaker (ed.). Frontier Forts of Iowa: Indians, Traders, and Soldiers, 1682–1862. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. pp. 55–74. ISBN 978-1-58729-831-8.

- Trask, Kerry A. Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America, (Google Books), Henry Holt: 2006, p. 109, 308, (ISBN 0805077588), pp. 220-221. Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- Lewis, James. "The Black Hawk War of 1832: FAQ Archived September 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine," Abraham Lincoln Digitization Project, Northern Illinois University. Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- Nolan, David J. (2009). "Fort Johnson, Cantonment Davis, and Fort Edwards". In William E. Whittaker (ed.). Frontier Forts of Iowa: Indians, Traders, and Soldiers, 1682–1862. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. pp. 85–94. ISBN 978-1-58729-831-8.

- Stevens, Walter B. (1921). Centennial History of Missouri (The Center State) One Hundred Years in the Union. St. Louis: S. J. Clarke.

- Black Hawk (1916) [1834]. Milo M. Quaife (ed.). Life of Black Hawk, Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak. Chicago: Lakeside Press. pp. 66–68. ISBN 9780608437781.

- Lewis, James. "The Black Hawk War of 1832 Archived August 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine," Abraham Lincoln Digitization Project, Northern Illinois University. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- "May 14: Black Hawk's Victory at the Battle of Stillman's Run Archived August 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine," Historic Diaries: The Black Hawk War, Wisconsin State Historical Society. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- "’I Am a Sauk... I Am a Warrior’ Archived January 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine." Black Hawk State Historic Site. Black Hawk Park & Foundation. Web. September 26, 2014.

- Harmet, "Apple River Fort," p. 13.

- Lewis, James. "Introduction Archived April 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine," The Black Hawk War of 1832, Abraham Lincoln Digitization Project, Northern Illinois University. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- Lewis, "Introduction."

- ""May 21, Indian Creek, Ill.: Abduction of the Hall Sisters" Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Historic Diaries: The Black Hawk War, Wisconsin State Historical Society. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- Matile, Roger. "The Black Hawk War: Massacre at Indian Creek Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine," Ledger-Sentinel (Oswego, Illinois), May 31, 2007, Retrieved September 20, 2007

- ""The Killing of Felix St. Vrain" Archived February 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Historic Diaries: Black Hawk War, Wisconsin Historical Society, Retrieved September 20, 2007

- Lewis, James. "The Black Hawk War of 1832" Archived 2009-06-19 at the Wayback Machine, Abraham Lincoln Digitization Project, Northern Illinois University, p. 2D. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- McCann, Dennis. "Black Hawk's name, country's shame lives on", Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, April 28, 2007. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- Smith, William C. Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour, pp. 842–843.

- Jung, p. 182.

- Trask, pp. 294–95.

- "Lincoln/Net: The Black Hawk War". Lincoln/Net. Northern Illinois University. Retrieved: May 3, 2015.

- "Black Hawk Remembers Village Life Along the Mississippi," History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web, George Mason University. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- Ford, Thomas (1854). A History of Illinois. Chicago: Griggs and Co. pp. 110–111. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- Atwater, Caleb. Remarks Made of A Tour to Prairie du Chien: Thence to Washington City, in 1829. Columbus, OH: Isaac N. Whiting, 1831

- Van der Zee, Jacob (1913) "Old Fort Madison: Some Source Materials", Iowa Journal of History and Politics Vol. 11.

- Johnson, W.F. (1919) History of Cooper County, Missouri. Topeka: Historical Publishing Co., p. 62.

- Indian Treaties 1795 to 1862 Vol. XX - Sauk & Fox L.S. Watson (ed.) 1993

- Campbell, James W. (1884) "Address of Capt. Jas. W. Campbell.", in Report of the Organization and First Reunion of the Tri-State Old Settlers' Association of Illinois, Missouri and Iowa, edited by J. H. Cole and J. M. Schaffer, pp. 33–38, Keokuk: IA, Tri-State Printing

- Caleb Atwater (1829) Remarks Made of A Tour to Prairie du Chien: Thence to Washington City (published 1831, pp. 60-62)

- Trask, Kerry (2006) Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America. Henry Holt. pp. 75-80.

- Andreas Atlas of Iowa", 1903, "Van Buren Co. Early History" and "Davis Co. Early History"

- Antrobus, Augustine M. History of Des Moines County Iowa and Its People Volume 1. Chicago: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1915; pp. 110-111

- Antrobus, Augustine M. (1915) History of Des Moines County, Iowa: And Its People, Vol. 1, p. 141 S.J. Clarke, Chicago.

- "Makataimeshekiakiak: Black Hawk and his War". Davenport Public Library. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- "BLACK HAWK'S VARNISHED BONES.; THEY ARE BELIEVED TO BE LYING UNMARKED IN A POTTER'S FIELD". New York Times. September 25, 1891. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- "Chief Blackhawk (1760 - 1838)". Find A Grave Memorial, findagrave.com. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "Black Hawk State Historic Site - History". blackhawkpark.org. Archived from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- Native peoples A to Z: a reference guide to native peoples of the western hemisphere, Vol. 8 (2nd ed.). Hamburg, Mich.: Native American Books. 2009. pp. 1784–785. ISBN 978-1878592736. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- Christina Boggs. "Chief Black Hawk: Biography & Facts". Study.com. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- Wesson, Sarah. "Black Hawk Makataimeshekiakiak: Black Hawk and his War". Davenport (Iowa) Public Library. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- "The Life of Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, or Black Hawk, 1833 summary". Wisconsin Historical Society

- Oregon Sculpture Trail Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, The Eternal Indian, City of Oregon. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

- Shannon, B. Clay. Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History, (Google Books), iUniverse, New York: 2006, p. 215, (ISBN 0595397239). Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- County Chronicles: A Vivid Collection of Fayette County, Pennsylvania Histories, (Google Books), Mechling Bookbindery: 2004, pp. 129–30, (ISBN 0976056348). Retrieved October 4, 2007.

- Jason Berry (1995). The Spirit of Blackhawk: a Mystery of Africans and Indians. University Press of Mississippi.

- Jacobs, Claude F.; Kaslow, Andrew J. (1991). The Spiritual Churches of New Orleans Origins, Beliefs, and Rituals of an African-American Religion. The University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 1-57233-148-8.

- Smith, Michael (1992). Spirit World: Pattern in the Expressive Folk Culture of New Orleans. Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-0-88289-895-7.

- "History", Chicago Blackhawks

- "Tri-Cities Blackhawks Jersey History | Authentic Jerseys". Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- "Bensenville School District 2, IL - Website - Blackhawk Middle School". Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Hammer, Lisa (May 30, 2019). "Old Native American hunting grounds near wind farm". QCOnline. Moline Dispatch & Rock Island Argus. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- "About Us - History". blackhawkcc.com. Archived from the original on August 11, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "Southwest Wisconsin Conference". Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "Fort High won't drop 'Blackhawks' name". Daily Jefferson County Union. February 17, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "Local Filmmaker To Debut 'Big Chief, Black Hawk' At American Black Film Festival". October 5, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

Further reading

- Brown, Nicholas A. and Sarah E. Kanouse. Re-Collecting Black Hawk: Landscape, Memory, and Power in the American Midwest. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015.

External links

- Black Hawk, Antoine LeClair (interpreter), and J.B. Patterson, ed. Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak or Black Hawk, Embracing the tradition of his nation--Indian wars in which he has been engaged--cause of joining the British in their late war with America, and its history--description of the Rock River village--manners and customs--encroachments by the whites, contrary to treaty--removal from his village in 1831. With an account of the cause and general history of the late war, his surrender and confinement at Jefferson Barracks, and travels through the United States. Boston: Russell, Odiorn & Metcalf, 1834

- Works by or about Black Hawk at Internet Archive

- Black Hawk with his son Whirling Thunder (1833), by John Wesley Jarvis, Gilcrease Museum

- "Black Hawk State Historic Site", Illinois History

- "Black Hawk Surrender Speech", State Department

- "Black Hawk (Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak)", in John E. Hallwas, ed. Illinois Literature: The Nineteenth Century, Macomb, IL: Illinois Heritage Press, 1986

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Black Hawk at Find a Grave