Bladder

The bladder is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys before disposal by urination. In humans the bladder is a distensible organ that sits on the pelvic floor. Urine enters the bladder via the ureters and exits via the urethra. The typical adult human bladder will hold between 300 and 500 ml (10.14 and 16.91 fl oz) before the urge to empty occurs, but can hold considerably more.[1][2]

| Bladder | |

|---|---|

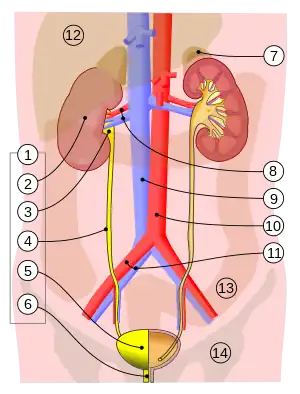

1. Human urinary system: 2. Kidney, 3. Renal pelvis, 4. Ureter, 5. Bladder, 6. Urethra. (Left side with frontal section) 7. Adrenal gland Vessels: 8. Renal artery and vein, 9. Inferior vena cava, 10. Abdominal aorta, 11. Common iliac artery and vein With transparency: 12. Liver, 13. Large intestine, 14. Pelvis | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Urogenital sinus |

| System | Urinary system |

| Artery | Superior vesical artery Inferior vesical artery Umbilical artery Vaginal artery |

| Vein | Vesical venous plexus |

| Nerve | Vesical nervous plexus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vesica urinaria |

| MeSH | D001743 |

| TA98 | A08.3.01.001 |

| TA2 | 3401 |

| FMA | 15900 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The Latin phrase for "urinary bladder" is vesica urinaria, and the term vesical or prefix vesico - appear in connection with associated structures such as vesical veins. The modern Latin word for "bladder" – cystis – appears in associated terms such as cystitis (inflammation of the bladder).

Structure

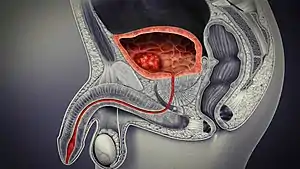

In humans, the bladder is a hollow muscular organ situated at the base of the pelvis. In gross anatomy, the bladder can be divided into a broad fundus, a body, an apex, and a neck.[3] The apex (also called the vertex) is directed forward toward the upper part of the pubic symphysis, and from there the median umbilical ligament continues upward on the back of the anterior abdominal wall to the umbilicus. The peritoneum is carried by it from the apex on to the abdominal wall to form the middle umbilical fold. The neck of the bladder is the area at the base of the trigone that surrounds the internal urethral orifice that leads to the urethra.[3] In males the neck of the urinary bladder is next to the prostate gland.

The bladder has three openings. The two ureters enter the bladder at ureteric orifices, and the urethra enters at the trigone of the bladder. These ureteric openings have mucosal flaps in front of them that act as valves in preventing the backflow of urine into the ureters,[4] known as vesicoureteral reflux. Between the two ureteric openings is a raised area of tissue called the interureteric crest.[3] This makes the upper boundary of the trigone. The trigone is an area of smooth muscle that forms the floor of the bladder above the urethra.[5] It is an area of smooth tissue for the easy flow of urine into and from this part of the bladder - in contrast to the irregular surface formed by the rugae.

The walls of the bladder have a series of ridges, thick mucosal folds known as rugae that allow for the expansion of the bladder. The detrusor muscle is the muscular layer of the wall made of smooth muscle fibers arranged in spiral, longitudinal, and circular bundles.[6] The detrusor muscle is able to change its length. It can also contract for a long time whilst voiding, and it stays relaxed whilst the bladder is filling.[7] The wall of the urinary bladder is normally 3–5 mm thick.[8] When well distended, the wall is normally less than 3 mm.

Nearby structures

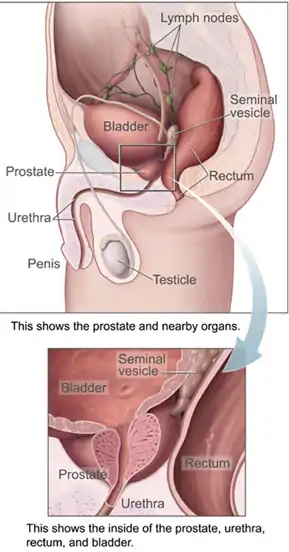

In men, the prostate gland lies outside the opening for the urethra. The middle lobe of the prostate causes an elevation in the mucous membrane behind the internal urethral orifice called the uvula of urinary bladder. The uvula can enlarge when the prostate becomes enlarged.

The bladder is located below the peritoneal cavity near the pelvic floor and behind the pubic symphysis. In men, it lies in front of the rectum, separated by the recto-vesical pouch, and is supported by fibres of the levator ani and of the prostate gland. In women, it lies in front of the uterus, separated by the vesico-uterine pouch, and is supported by the elevator ani and the upper part of the vagina.[8]

Blood and lymph supply

The bladder receives blood by the vesical arteries and drained into a network of vesical veins.[9] The superior vesical artery supplies blood to the upper part of the bladder. The lower part of the bladder is supplied by the inferior vesical artery, both of which are branches of the internal iliac arteries.[9] In females, the uterine and vaginal arteries provide additional blood supply.[9] Venous drainage begins in a network of small vessels on the lower lateral surfaces of the bladder, which coalesce and travel with the lateral ligaments of the bladder into the internal iliac veins.[9]

The lymph drained from the bladder begins in a series of networks throughout the mucosal, muscular and serosal layers. These then form three sets of vessels: one set near the trigone draining the bottom of the bladder; one set draining the top of the bladder; and another set draining the outer undersurface of the bladder. The majority of these vessels drain into the external iliac lymph nodes.[9]

Nerve supply

The bladder receives both sensory and motor supply from sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems.[9] The motor supply from both sympathetic fibers, most of which arise from the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses and nerves, and from parasympathetic fibers, which come from the pelvic splanchnic nerves.[10]

Sensation from the bladder, relating to distension or to irritation (such as by infection or a stone) is transmitted primarily through the parasympathetic nervous system.[9] These travel via sacral nerves to S2-4.[11] From here, sensation travels to the brain via the dorsal columns in the spinal cord.[9]

Microanatomy

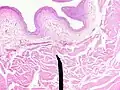

When viewed under a microscope the bladder can be seen to have an inner lining (called epithelium), three layers of muscle fibres, and an outer adventitia.[6]

The inner wall of the bladder is called urothelium, a type of transitional epithelium formed by three to six layers of cells; the cells may become more cuboidal or flatter depending on whether the bladder is empty or full.[6] Additionally, these are lined with a mucous membrane consisting of a surface glycocalyx that protects the cells beneath it from urine.[12] The epithelium lies on a thin basement membrane, and a lamina propria.[6] The mucosal lining also offers a urothelial barrier against the passing of infections.[13]

These layers are surrounded by three layers of muscle fibres arranged as an inner layer of fibres orientated longitudinally, a middle layer of circular fibres, and an outermost layer of longitudinal fibres; these form the detrusor muscle, which can be seen with the naked eye.[6]

The outside of the bladder is protected by a serous membrane called adventitia.[6][14]

Vertical section of bladder wall

Vertical section of bladder wall Layers of the bladder wall and cross-section of the detrusor muscle

Layers of the bladder wall and cross-section of the detrusor muscle Anatomy of the male bladder, showing transitional epithelium and part of the wall in a histological cut-out

Anatomy of the male bladder, showing transitional epithelium and part of the wall in a histological cut-out

Development

In the developing embryo, at the hind end lies a cloaca. This, over the fourth to the seventh week, divides into a urogenital sinus and the beginnings of the anal canal, with a wall forming between these two inpouchings called the urorectal septum.[15] The urogenital sinus divides into three parts, with the upper and largest part becoming the bladder; the middle part becoming the urethra, and the lower part changes depending on the biological sex of the embryo.[15]

The human bladder derives from the urogenital sinus, and it is initially continuous with the allantois. The upper and lower parts of the bladder develop separately and join around the middle part of development.[5] At this time the ureters move from the mesonephric ducts to the trigone.[5] In males, the base of the bladder lies between the rectum and the pubic symphysis. It is superior to the prostate, and separated from the rectum by the recto-vesical pouch. In females, the bladder sits inferior to the uterus and anterior to the vagina; thus its maximum capacity is lower than in males. It is separated from the uterus by the vesico-uterine pouch. In infants and young children the urinary bladder is in the abdomen even when empty.[16]

Function

Urine, excreted by the kidneys, collects in the bladder because of drainage from two ureters, before disposal by urination (micturition).[11] Urine leaves the bladder via the urethra, a single muscular tube ending in an opening called the urinary meatus, where it exits the body.[9] Urination involves coordinated muscle changes involving a reflex based in the spine, with higher inputs from the brain.[11] During urination, the detrusor muscle contracts, and the external urinary sphincter and muscles of the perineum relax, allowing urine to pass through the urethra and out of the body.[11]

The urge to pass urine stems from stretch receptors that activate when between 300 - 400 mL urine is held within the bladder.[11] As urine accumulates, the rugae flatten and the wall of the bladder thins as it stretches, allowing the bladder to store larger amounts of urine without a significant rise in internal pressure.[17] Urination is controlled by the pontine micturition center in the brainstem.[18]

Stretch receptors in the bladder signal the parasympathetic nervous system to stimulate the muscarinic receptors in the detrusor to contract the muscle when the bladder is distended.[19] This encourages the bladder to expel urine through the urethra. The main receptor activated is the M3 receptor, although M2 receptors are also involved and whilst outnumbering the M3 receptors they are not so responsive.[20]

The main relaxant pathway is via the adenylyl cyclase cAMP pathway, activated via the β3 adrenergic receptors. The β2 adrenergic receptors are also present in the detrusor and even outnumber β3 receptors, but they do not have as important an effect in relaxing the detrusor smooth muscle.[7][21][22]

Clinical significance

Inflammation and infection

Cystitis refers to infection or inflammation of the bladder. It commonly occurs as part of a urinary tract infection.[23] In adults, it is more common in women than men, owing to a shorter urethra. It is common in males during childhood, and in older men where an enlarged prostate may cause urinary retention.[23] Other risk factors include other causes of blockage or narrowing, such as prostate cancer or the presence of vesico-ureteric reflux; the presence of outside structures in the urinary tract, such as urinary catheters; and neurologic problems that make passing urine difficult.[23] Infections that involve the bladder can cause pain in the lower abdomen (above the pubic symphysis, so called "suprapubic" pain), particularly before and after passing urine, and a desire to pass urine frequently and with little warning (urinary urgency).[23] Infections are usually due to bacteria, of which the most common is E coli.[23]

When a urinary tract infection or cystitis is suspected, a medical practitioner may request a urine sample. A dipstick placed in the urine may be used to see if the urine has white blood cells, or the presence of nitrates which may indicate an infection. The urine specimen may be also sent for microbial culture and sensitivity to assess if a particular bacteria grows in the urine, and identify its antibiotic sensitivities.[23] Sometimes, additional investigations may be requested. These might include testing the function of the kidneys by assessing electrolytes and creatinine; investigating for blockages or narrowing of the renal tract with an ultrasound, and testing for an enlarged prostate with a digital rectal examination.[23]

Urinary tract infections or cystitis are treated with antibiotics, many of which are consumed by mouth. Serious infections may require treatment with intravenous antibiotics.[23]

Interstitial cystitis refers to a condition in which the bladder is infected due to a cause that is not bacteria.[24][25]

Incontinence and retention

Frequent urination can be due to excessive urine production, small bladder capacity, irritability or incomplete emptying. Males with an enlarged prostate urinate more frequently. One definition of an overactive bladder is when a person urinates more than eight times per day.[26] An overactive bladder can often cause urinary incontinence. Though both urinary frequency and volumes have been shown to have a circadian rhythm, meaning day and night cycles,[27] it is not entirely clear how these are disturbed in the overactive bladder. Urodynamic testing can help to explain the symptoms. An underactive bladder is the condition where there is a difficulty in passing urine and is the main symptom of a neurogenic bladder. Frequent urination at night may indicate the presence of bladder stones.

Disorders of or related to the bladder include:

- Bladder exstrophy

- Bladder sphincter dyssynergia, a condition in which the sufferer cannot coordinate relaxation of the urethra sphincter with the contraction of the bladder muscles

- Paruresis

- Trigonitis

- Underactive bladder, a condition with its main symptom being urinary retention.[28]

Disorders of bladder function may be dealt with surgically, by re-directing the flow of urine or by replacement with an artificial urinary bladder. The volume of the bladder may be increased by bladder augmentation. An obstruction of the bladder neck may be severe enough to warrant surgery.

Cancer

Cancer of the bladder is known as bladder cancer. It is usually due to cancer of the urothelium, the cells that line the surface of the bladder. Bladder cancer is more common after the age of 40, and more common in men than women;[29] other risk factors include smoking and exposure to dyes such as aromatic amines and aldehydes.[29] When cancer is present, the most common symptom in an affected person is blood in the urine; a physical medical examination may be otherwise normal, except in late disease.[29] Bladder cancer is most often due to cancer of the cells lining the ureter, called transitional cell carcinoma, although it can more rarely occur as a squamous cell carcinoma if the type of cells lining the urethra have changed due to chronic inflammation, such as due to stones or schistosomiasis.[29]

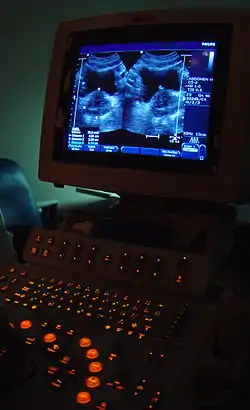

Investigations performed usually include collecting a sample of urine for an inspection for malignant cells under a microscope, called cytology, as well as medical imaging by a CT urogram or ultrasound.[29] If a concerning lesion is seen, a flexible camera may be inserted into the bladder, called cystoscopy, in order to view the lesion and take a biopsy, and a CT scan will be performed of other body parts (a CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis) to look for additional metastatic lesions.[29]

Treatment depends on the cancer's stage. Cancer present only in the bladder may be removed surgically via cystoscopy; an injection of the chemotherapeutic mitomycin C may be performed at the same time.[29] Cancers that are high grade may be treated with an injection of the BCG vaccine into the bladder wall, and may require surgical removal if it does not resolve.[29] Cancer that is invading through the bladder wall may be managed by complete surgical removal of the bladder (radical cystectomy), with the ureters diverted into a segment of part of ileum connected to a stoma bag on the skin.[29] Prognosis can vary markedly depending on the cancer's stage and grade, with a better prognosis associated with tumours found only in the bladder, that are low grade, that do not invade through the bladder wall, and that is papillary in visual appearance.[29]

Investigation

A number of investigations are used to examine the bladder. The investigations that are ordered will depend on the taking of a medical history and an examination. The examination may involve a medical practitioner feeling in the suprapubic area for tenderness or fullness that might indicate an inflamed or full bladder. Blood tests may be ordered that may indicate inflammation; for example a full blood count may demonstrate elevated white blood cells, or a C-reactive protein may be elevated in an infection.

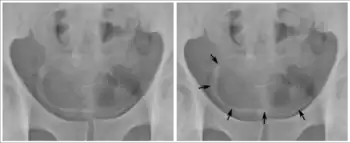

Some forms of medical imaging exist to visualise the bladder. A bladder ultrasound may be conducted to view how much urine is within the bladder, indicating urinary retention. A urinary tract ultrasound, conducted by a more trained operator, may be conducted to view whether there are stones, tumours or sites of obstruction within the bladder and urinary tract. A CT scan may also be ordered.

A flexible internal camera, called a cystoscope, can be inserted to view the internal appearance of the bladder and take a biopsy if required.

Urodynamic testing can help to explain the symptoms.

Animals

Mammals

All mammals have a urinary bladder. This structure begins as an embryonic cloaca. In the vast majority, this eventually becomes differentiated into a dorsal part connected to the intestine and a ventral part which becomes associated with the urinogenital passage and urinary bladder. The only mammals in which this does not take place are the platypus and the spiny anteater both of which retain the cloaca into adulthood.[30]

The mammalian bladder is an organ that regularly stores a hyperosmotic concentration of urine. It therefore is relatively impermeable and has multiple epithelial layers. The urinary bladder of the cetaceans (whales and dolphins) is proportionally smaller than that of land-dwelling mammals.[31]

Reptiles

In all reptiles, the urinogenital ducts and the anus both empty into an organ called a cloaca. In some reptiles, a midventral wall in the cloaca may open into a urinary bladder, but not all. It is present in all turtles and tortoises as well as most lizards but is lacking in the monitor lizard, the legless lizards. It is absent in the snakes, alligators, and crocodiles.[30]: p. 474

Many turtles, tortoises, and lizards have proportionally very large bladders. Charles Darwin noted that the Galapagos tortoise had a bladder which could store up to 20% of its body weight.[32] Such adaptations are the result of environments such as remote islands and deserts where water is very scarce.[33] Other desert-dwelling reptiles have large bladders that can store a long-term reservoir of water for up to several months and aid in osmoregulation.[34]

Turtles have two or more accessory urinary bladders, located lateral to the neck of the urinary bladder and dorsal to the pubis, occupying a significant portion of their body cavity.[35] Their bladder is also usually bilobed with a left and right section. The right section is located under the liver, which prevents large stones from remaining in that side while the left section is more likely to have calculi.[36]

Amphibians

Most aquatic and semi-aquatic amphibians have a membranous skin which allows them to absorb water directly through it. Some semi-aquatic animals also have similarly permeable bladder membrane.[37] As a result, they tend to have high rates of urine production to offset this high water intake, and have urine which is low in dissolved salts. The urinary bladder assists such animals to retain salts. Some aquatic amphibian such as Xenopus do not reabsorb water, to prevent excessive water influx.[38] For land-dwelling amphibians, dehydration results in reduced urine output.[39]

The amphibian bladder is usually highly distensible and among some land-dwelling species of frogs and salamanders may account for between 20% and 50% of their total body weight.[39]

Fish

The gills of most teleost fish help to eliminate ammonia from the body, and fish live surrounded by water, but most still have a distinct bladder for storing waste fluid. The urinary bladder of teleosts is permeable to water, though this is less true for freshwater dwelling species than saltwater species.[32]: p. 219 Most fish also have an organ called a swim-bladder which is unrelated to the urinary bladder except in its membranous nature. The loaches, pilchards, and herrings are among the few types of fish in which a urinary bladder is poorly developed. It is largest in those fish which lack an air bladder, and is situated in front of the oviducts and behind the rectum.[40] The urinary bladders of fish and tetrapods are thought to be analogous while the former's swim-bladders and latter's lungs are considered homologous.

Birds

In nearly all bird species, there is no urinary bladder per se.[41] Although all birds have kidneys, the ureters open directly into a cloaca which serves as a reservoir for urine, fecal matter, and eggs.[42]

Crustaceans

Unlike the urinary bladder of vertebrates, the urinary bladder of crustaceans both stores and modifies urine.[43] The bladder consists of two sets of lateral and central lobes. The central lobes sit near the digestive organs and the lateral lobes extend along the front and sides of the crustacean's body cavity.[43] The tissue of the bladder is thin epithelium.[43]

See also

References

- Boron, Walter F.; Boulpaep, Emile L. (2016). Medical Physiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 738. ISBN 9781455733286. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- Walker-Smith, John; Murch, Simon (1999). Cardozo, Linda (ed.). Diseases of the Small Intestine in Childhood (4 ed.). CRC Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781901865059. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- Netter, Frank H. (2014). Atlas of Human Anatomy Including Student Consult Interactive Ancillaries and Guides (6th ed.). Philadelphia, Penn.: W B Saunders Co. pp. 346–8. ISBN 978-14557-0418-7.

- "SEER Training:Urinary Bladder". training.seer.cancer.gov.

- Viana R, Batourina E, Huang H, Dressler GR, Kobayashi A, Behringer RR, Shapiro E, Hensle T, Lambert S, Mendelsohn C (October 2007). "The development of the bladder trigone, the center of the anti-reflux mechanism". Development. 134 (20): 3763–9. doi:10.1242/dev.011270. PMID 17881488.

- Young, Barbara; O'Dowd, Geraldine; Woodford, Phillip (2013). "Urinary system". Wheater's functional histology: a text and colour atlas (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 315–7. ISBN 9780702047473.

- Andersson KE, Arner A (July 2004). "Urinary bladder contraction and relaxation: physiology and pathophysiology". Physiol. Rev. 84 (3): 935–86. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.324.7009. doi:10.1152/physrev.00038.2003. PMID 15269341.

- Page 12 in: Uday Patel (2010). Imaging and Urodynamics of the Lower Urinary Tract. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781848828360.

- Standring, Susan, ed. (2016). "Urinary bladder". Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia. pp. 1255–1261. ISBN 9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Moore, Keith; Anne Agur (2007). Essential Clinical Anatomy, Third Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-7817-6274-8.

- Barrett, Kim E; Barman, Susan M; Yuan, Jason X-J; Brooks, Heddwen (2019). "37. Renal function & Micturition: The Bladder". Ganong's review of medical physiology (26th ed.). New York. pp. 681–682. ISBN 9781260122404. OCLC 1076268769.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stromberga, Z; Chess-Williams, R; Moro, C (7 March 2019). "Histamine modulation of urinary bladder urothelium, lamina propria and detrusor contractile activity via H1 and H2 receptors". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 3899. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.3899S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-40384-1. PMC 6405771. PMID 30846750.

- Janssen, DA (January 2013). "The distribution and function of chondroitin sulfate and other sulfated glycosaminoglycans in the human bladder and their contribution to the protective bladder barrier". The Journal of Urology. 189 (1): 336–42. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.022. PMID 23174248.

- Fry, CH; Vahabi, B (October 2016). "The Role of the Mucosa in Normal and Abnormal Bladder Function". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 119 (Suppl 3): 57–62. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12626. PMC 5555362. PMID 27228303.

- Sadley, TW (2019). "Bladder and urethra". Langman's medical embryology (14th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 263–66. ISBN 9781496383907.

- Moore, Keith L.; Dalley, Arthur F (2006). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781736398.

- Marieb, Mallatt. "23". Human Anatomy (5th ed.). Pearson International. p. 700.

- Purves, Dale (2011). Neuroscience (5. ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. p. 471. ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

- Giglio, D; Tobin, G (2009). "Muscarinic receptor subtypes in the lower urinary tract". Pharmacology. 83 (5): 259–69. doi:10.1159/000209255. PMID 19295256.

- Uchiyama, T; Chess-Williams, R (December 2004). "Muscarinic receptor subtypes of the bladder and gastrointestinal tract". Journal of Smooth Muscle Research = Nihon Heikatsukin Gakkai Kikanshi. 40 (6): 237–47. doi:10.1540/jsmr.40.237. PMID 15725706.

- Moro, Christian; Tajouri, Lotti; Chess-Williams, Russ (2013). "Adrenoceptor Function and Expression in Bladder Urothelium and Lamina Propria". Urology. 81 (1): 211.e1–211.e7. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2012.09.011. PMID 23200975.

- Chancellor, M. B.; Yoshimura, N. (2004). "Neurophysiology of Stress Urinary Incontinence". Rev. Urol. 6 (Suppl 3): S19–28. PMC 1472861. PMID 16985861.

- Davidson's 2018, pp. 426–429.

- "Interstitial cystitis". Mayo Clinic. 14 September 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Glass, Cheryl, A.; Gunter, Debbie (2017). Glass, Cheryl, A.; Cash, Jill, C. (eds.). Family Practice Guidelines (4 ed.). New York: pringer Publishing Company, LLC. pp. 352–353. ISBN 978-0826177117.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Overactive Bladder". Cornell Medical College. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- Negoro, Hiromitsu (2012). "Involvement of urinary bladder Connexin43 and the circadian clock in coordination of diurnal micturition rhythm". Nature Communications. 3: 809. Bibcode:2012NatCo...3..809N. doi:10.1038/ncomms1812. PMC 3541943. PMID 22549838.

- C, Moro; C, Phelps; V, Veer; J, Clark; P, Glasziou; Kao, Tikkinen; Am, Scott (24 November 2021). "The effectiveness of parasympathomimetics for treating underactive bladder: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Neurourology and Urodynamics. 41 (1): 127–139. doi:10.1002/nau.24839. ISSN 1520-6777. PMID 34816481. S2CID 244530010.

- Ralston, Stuart H.; Penman, Ian D.; Strachan, Mark W.; Hobson, Richard P. (eds.) (2018). "Urothelial tumours". Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (23rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 435–6. ISBN 978-0-7020-7028-0.

{{cite book}}:|first4=has generic name (help) - Herbert W. Rand (1950). The Chordates. Balkiston.

- John Hunter (26 March 2015). The Works of John Hunter, F.R.S. Cambridge University. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-108-07960-0.

- P.J. Bentley (14 March 2013). Endocrines and Osmoregulation: A Comparative Account in Vertebrates. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-662-05014-9.

- Paré, Jean (11 January 2006). "Reptile Basics: Clinical Anatomy 101" (PDF). Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference. 20: 1657–1660.

- Davis, Jon R.; DeNardo, Dale F. (15 April 2007). "The urinary bladder as a physiological reservoir that moderates dehydration in a large desert lizard, the Gila monster Heloderma suspectum". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (8): 1472–1480. doi:10.1242/jeb.003061. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 17401130.

- Wyneken, Jeanette; Witherington, Dawn (February 2015). "Urogenital System" (PDF). Anatomy of Sea Turtles. 1: 153–165.

- Divers, Stephen J.; Mader, Douglas R. (2005). Reptile Medicine and Surgery. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 481, 597. ISBN 9781416064770.

- Urakabe, Shigeharu; Shirai, Dairoku; Yuasa, Shigekazu; Kimura, Genjiro; Orita, Yoshimasa; Abe, Hiroshi (1976). "Comparative study of the effects of different diuretics on the permeability properties of the toad bladder". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Comparative Pharmacology. 53 (2): 115–119. doi:10.1016/0306-4492(76)90063-0. PMID 5237.

- Shibata, Yuki; Katayama, Izumi; Nakakura, Takashi; Ogushi, Yuji; Okada, Reiko; Tanaka, Shigeyasu; Suzuki, Masakazu (2015). "Molecular and cellular characterization of urinary bladder-type aquaporin in Xenopus laevis". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 222: 11–19. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.09.001. PMID 25220852.

- Laurie J. Vitt; Janalee P. Caldwell (25 March 2013). Herpetology: An Introductory Biology of Amphibians and Reptiles. Academic. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-12-386920-3.

- Owen, Richard (1843). Lectures on the comparative anatomy and physiology of the invertebrate animals. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 283–284.

- Cornell University. Laboratory of Ornithology (19 September 2016). Handbook of Bird Biology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-29105-4.

- Charles Knight (1854). The English Cyclopaedia: A New Dictionary of Universal Knowledge. Bradbury and Evans. p. 136.

- Nonmammalian animal models for biomedical research. Woodhead, Avril D. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press. 1989. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-8493-4763-7. OCLC 18816053.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

- Books

- editor-in-chief, Susan Standring; section editors, Neil R. Borley et al., ed. (2008). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

- Ralston, Stuart H.; Penman, Ian D.; Strachan, Mark W.; Hobson, Richard P. (eds.) (2018). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (23rd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-7028-0.

{{cite book}}:|first4=has generic name (help)

External links

- Anatomy photo: Urinary/mammal/bladder/bladder1 - Comparative Organology at University of California, Davis – "Mammal, bladder (LM, Medium)"

- Bladder (ISSN 2327-2120) – An open-access journal on bladder biology and diseases.