Boško Čolak-Antić

Boško I. Čolak-Antić (Serbian Cyrillic: Бошко Чолак-Антић; 21 August 1871 – 24 March 1949), also known as Boshko Tcholak-Antitch,[a] was a Serbian diplomat, and Marshal of the Court of the Kingdom of Serbia and Kingdom of Yugoslavia, He served as ambassador in the Middle East as well as in several European capitals. From a prominent noble military family, he was a skilled diplomat who played a significant role during the critical era of the First World War.[1]

Boško Čolak-Antić | |

|---|---|

Бошко Чолак-Антић | |

Boško I. Čolak-Antić c. 1903 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 August 1871 Kragujevac, principality of Serbia |

| Died | March 24, 1949 (aged 77) Belgrade, Yugoslavia |

| Relations | Čolak-Anta Simeonović |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | Vojin Čolak-Antić (brother) |

| Alma mater | University of Geneva (PhD, 1894) |

| Occupation | Diplomat |

Early life and family

Boško Čolak-Antić was born in Kragujevac, Principality of Serbia into the Čolak-Antić family, an influential Serbian family with a long military tradition; the first son of Colonel Ilija Čolak-Antić commander of the Ibar Army during the Serbo-Turkish war, and Jelena (née Matić). Čolak-Antić's maternal grandfather was prominent Liberal politician and philosopher Dimitrije Matić who was President of the National Assembly when Serbia gained independence from the Ottoman Empire. He had a younger brother Vojin Čolak-Antić, a divisional general in the army, and a sister Jovanka married to writer Ilija Vukićević. Čolak-Antić was the great-grandson of famous Vojvoda Čolak-Anta Simeonović, one of the leaders of the First Serbian Uprising of 1804. After graduating from secondary school, he went to study law at the University of Geneva, where, in 1894, he graduated as doctor of law.[2] He returned to Serbia and began his career at the Ministry of Finance before transferring to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1898.[3]

Diplomatic service

His diplomatic career started in 1899 when Čolak-Antić was appointed Secretary of the Serbian Representation in Sofia then Minister Plenipotentiary to the Principality of Bulgaria; three years after Ferdinand had been recognized as king of the Bulgarians by the Great Powers, at a time of turmoil in neighbouring Turkish provinces; Čolak-Antić expressed concerned about the secret talks happening between the Bulgarians and the Ottomans regarding the unrest in the region of Macedonia, bypassing the three other members representing the different communities Serbian, Greek and Vlach (Aromanians and Megleno-Romanians), and warn his government about Bulgaria's expansionist intentions. Macedonia was the focus of diplomatic and political activity of both Bulgaria and Serbia, the ascendancy of nationalistic visions meant that both were interested in partitioning the Turkish territory and claiming it as historically theirs while making preparations for war with the Ottoman Empire. Čolak-Antić's mission in Bulgaria ended in 1903, that same year, the outbreak of the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising in Macedonia, a failed rebellion organised by Bulgarian secret revolutionary society intensified the path towards war.[4]

After the change of dynasty and the coronation of Peter I of Serbia, on 21 September 1904, Čolak-Antić became acting Marshal of the Royal Court of Serbia, a position he will occupy until 1907 while still executing diplomatic missions around Europe.[5]

His next appointment was in Cairo where he served as ambassador from 1908 until 1912, at the time the country was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire under British dominance. In Egypt he started a lifelong friendship with French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero, who served as director of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Maspero mentioned Čolak-Antić multiple times in his memoirs; he returned to Serbia at the start of the Balkan wars.[6]

On 9 January 1914, royal embassies and consulates and informed “by encrypted telegram“ that diplomatic relations between Bulgaria and Serbia have been restored, less than a year after Bulgaria had attacked its former ally, losing the second Balkan War, and for the first time since Bulgaria became a Kingdom. Despite the complex intertwining of Serbian Bulgarian interests, as a result of the desire for stability in international relations, which was of interest to both countries and due to internal pressures, diplomatic relations between Bulgaria and Serbia were restored fairly quickly.[7] At the beginning of 1914 Boško Čolak-Antić is appointed minister plenipotentiary in Sofia, his nomination is accepted and validated by the Bulgarian government. On 4 February 1914 he hands over his letters of credit.[8]

First World War

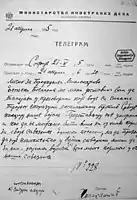

On 28 June 1914 Archduke Franz Ferdinand is assassinated in Sarajevo, a month later, on 28 July, Austria-Hungary began hostilities by bombarding Belgrade, effectively beginning the First World War. Bulgaria declared its neutrality but entered at the same time secret negotiations with Austria-Hungary and Germany. In a telegram dated 1 July 1914, Čolak-Antić warned Prime Minister Nikola Pašić that through a loan offered by the German Empire, the Bulgarian government was bound to the camp of the Triple Alliance and therefore presented an imminent danger to Serbia.[9]

In August 1914 Austro-Hungarian forces entered deep into Serbia, occupying the north of the country, the government had to relocate but by mid-December against all odds the Serbian forces defeated the invader and pushed them out of the country. The pressure of war transformed diplomacy too, Boško Čolak-Antić found himself entrusted with the important task of bringing new partners into the war while maintaining the links between allies and preventing them from going over to the other side.[10] In April 1915 Čolak-Antić warned his government in a telegram that the Italians were participating in secret talks with the Triple Entente about annexing lands in Dalmatia and ports in Albania in exchange for joining the Allies side.[1]

On 10 August Čolak-Antić met with the Bulgarian prime minister Vasil Radoslavov, bringing forward a proposal, by the Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić, for a mutual settlement which would have resolved all disputed between the two countries, in particular the issue of prisoners of war, without the need of meditation by Allied diplomats. Radslavov rejected the proposal asking for more time. Čolak-Antić informed his government that the participation of Bulgaria on the side of the Central Powers seemed inevitable.[11] On 24 August 1915 Radslavov signed a secret agreement with the minister plenipotentiary of the German Empire, followed by a treaty of friendship and alliance between the two countries. Later that day Radslavov signed a military convention with Germany and Austria-Hungary, placing Bulgaria in the camp of the Central Powers and as such an enemy of Serbia, Russia, France and Britain and an ally of the Ottomans.[12]

On 9 September 1915, tsar Ferdinand and prime minister Radoslavov signed a decree of general mobilization. Numerous rumors of preparations for mobilization started to spread, Čolak-Antić warned Pašić about the rumours but the Bulgarian government kept denying.[13] In Serbia Field Marshal Radomir Putnik, the Serbian Chief of the General Staff, suggested launching a preventive attack while Bulgaria was mobilizing, their only chance before Austria attacked again. To the consternation of Boško Čolak-Antić, Edward Grey, British foreign secretary, chose to give Bulgaria one more chance with the reason that Bulgaria had assured the allies of her pacific intentions. The Triple Entente tried to calm the situation by giving an ultimatum to Bulgaria, without success. On 23 September 1915, the Triple Entente severed diplomatic relations with Bulgaria. In connection to that, as well as on the basis of orders from his government, Serbian plenipotentiary minister Čolak-Antić left Bulgaria.[7]

On 6 October 1915 the combined armies of Germany and Austria-Hungary launched the invasion of Serbia, a few days later, on 11 October, without any previous declaration of war, Bulgaria joined the invaders and attacked the greatly outnumbered Serbian army from the rear. Čolak-Antić returned immediately home to volunteer. On 31 October he arrived in Raška to meet the representatives of France, Great Britain, Russia and Italy, after spending the night there, Čolak-Antić brought them to Mitrovica to meet with the King, Nikola Pašić and the Serbian government. He joined the retreat through Albania to Corfu, where he followed the Serbian Government in exile.[14]

Later that year he relocated to Salonika with the rest of the army and where his brother Vojin Čolak-Antić, now Colonel, is the commander of the 3rd Serbian Cavalry Brigade.[14] In Salonika he took part in the controversial trial of Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević known as Apis and other members of the Black Hand.[12] During that time, Čolak-Antić is appointed Marshal of the Court, of this period of intrigue when politicians mistrusted military officers who mistrusted government, he famously declared:

Trust no one. Suspect everyone

— Boško Čolak-Antić, [15]

For the rest of the war, while the government was between Corfu, Salonika and Nice and the army fought on the Salonika front, Serbia was divided and occupied and under harsh military government by respectively Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary. Čolak-Antić is sent on missions for the government around Europe.[15]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

_Stockholm_c.1919.jpg.webp)

After the war and the ensuing reshuffle he became Ambassador of the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Sweden, taking residence in Stockholm on 18 February 1918 staying until 1920.[3]

On 3 March 1920 Čolak-Antić was appointed envoy extraordinary then ambassador to Romania, he was based in Bucharest where he represented the kingdom in the talks of the Little Entente with Czechoslovakia and Romania in order to build a common defense against Hungary. On 7 July 1923 in Bucharest, after the two kingdoms agreed to conclude a defence Convention, Tcholak-Antitch, as Plenipotentiary Delegate, signed the Convention on the Defence Alliance between the kingdom of Romania and the kingdom of Yugoslavia. The first article of the Convention indicated that: "In the case of an unprovoked attack by Hungary on either High Contracting Party, the other Party shall come to aid the attacked Party in accordance with the Treaty provided for". While in Bucharest he kept a record that would later become a book about his experience.[16]

At the beginning of July 1929, as the head of the Yugoslav delegation, Čolak-Antić, was invited back to Belgrade to receive new instructions from the Minister of Foreign Affairs Vojislav Marinković.[17] When Romania started to get closer to Bulgaria as well as improving its relations with Hungary, Boško Čolak-Antić demanded a meeting of the Little Entente at which Romania had to explain its position.[18] Boško Čolak-Antić complained of Romanian military authorities’ 'lack of frankness' and increasingly questioned the military value of the Little Entente and the Romanian-Yugoslav ties.[18] Five years later, Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary will all be joining Germany and the Axis Powers leaving Yugoslavia alone to face Nazi Germany and its allies.[19]

In 1935 he goes back to Yugoslavia after being appointed Marshal of the Royal Court of King Peter II, he remained in that capacity until 1941.[20]

Personal life

Boško Čolak-Antić was a keen sportsman throughout his life, he was the founder of the Serbian Cycling Society in 1885, the main national governing body for cycle sport in Serbia. He was also an accomplished equestrian and a practitioner of martial arts.[21]

On 13 March 1905, after judging that an article by a journalist has insulted the memory of his late father, war hero Colonel Ilija Čolak-Antić, he demanded reparations to the author Milan Pavlović, Editor-in-Chief of the newspaper Opozicija, challenging him to a duel.[22] Čolak-Antić wanted to fight with sabers but following objections from the other party, it was decided that the duel would take place with pistols, on 16 March at 4 pm, on the clearing of Banovo Brdo, at a distance of 20 steps between the opponents; Dr Roman Sondermajer would be present together with the witnesses. Both opponents arrived on time, refused to settle the dispute, fired their guns and remarkably both remained unharmed.[21] The event was reported by Čolak-Antić’s brother in law, journalist, and founder of the newspaper Politika, Vladislav F. Ribnikar: "Yesterday at exactly 4 o'clock in the afternoon, there was a duel between Mr. Boško Čolak-Antić, Marshal of the Court and Milan Pavlović, Editor-in-Chief of Opozicija”.[22] Government officials chose to stay silent on the issue, even though by law, duels were prohibited. Opozicija, the fiercest critic of the government, stopped publishing a month later.[21]

During his service in Bucharest, on a formal reception in the Romanian court, Čolak-Antić organised together with Dr. Momčilo Ninčić the arrangements of marrying Romanian princess Maria to Alexander Karadjordjević. In July 1915 he was described, during negotiations with Bulgaria about joining the war on the Allies side, as possessing “a refined courtesy and a real impartiality which dictated all the actions of his important position during a very delicate situation”.[23] According to French historian Marcel Dunan, He was “a perfect gentleman, an aristocrat, who could have passed as a member of the Court of Henry III”.[23]

Publications

- Edouard Benes et La Petite Entente, ed. Melantrich, 1934.

References

Citations

- Foreign Office 2008, p. 1224.

- Ljubinka Trgovčević 2003.

- Robert L. Jarman 1997, p. 668.

- Daskalov, R.; Vezenkov, A. (2015). Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume Three: Shared Pasts, Disputed Legacies. Balkan Studies Library. Brill. p. 381. ISBN 978-90-04-29036-5.

- Robert L. Jarman 1997, p. 129.

- Foreign Office 2008, p. 777.

- Rudić et al. 2018, p. 432.

- Institute of Historical Research, Rudić & Milkić 2015, p. 74.

- F.H. Hinsley & Keith Wilson 2016, p. 87.

- Hall, R.C. (1996). Bulgaria's Road to the First World War. East European Monographs; 460 Translations from the Asian Cl. East European Monographs. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-88033-357-3.

- Adamov, E.A.; Valski, S.; Glaussel, G.; Paris, V.; Chklaver, G.; Lozinskiĭ, L.; Institut des langues orientales (Russia) (1932). Constantinople et les detroits: documents secrets de l'ancien Ministère des affaires étrangères de Russie (in French). Les Éditions internationales. p. 119.

- Andrej Mitrović 2007, p. 187.

- Mishev, D.N. (1919). Un chapitre inconnu: réponse à M. N. Pachitch (in French). Impr. Petter, Giesser & Held. p. 19.

- Auguste Boppe 1916, pp. 757–787.

- "Encounter With History: Apis And King Alexander". Novosti (in Serbian). 2020-07-25.

- Čolak-Antić, B.; Beneš, E. (1934). Edouard Benes et La Petite Entente (in French). Melantrich.

- Popi, G. (1984). Yugoslav-Romanian relations, 1918-1941. Monografije (Univerzitet u Novom Sadu. Filozofski fakultet) (in Serbian). Sloboda. p. 82.

- Boia, E. (1993). Romania's Diplomatic Relations with Yugoslavia in the Interwar Period, 1919-1941. East European monographs. East European Monographs. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-88033-253-8.

- DiNardo, R.L.; Showalter, D.E. (2005). Germany and the Axis Powers from Coalition to Collapse. Modern war studies. University Press of Kansas. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7006-1412-7.

- Branislav Gligorijević 2002, p. 7.

- Marta Levai (2018-05-03). "The first Belgrade duel with pistols - Once upon a time in Belgrade". 011info - najbolji vodič kroz Beograd (in Serbian).

- Bokan, D. (2008). Politika: mit, hronika, enciklopedija (in Serbian). Politika. p. 134. ISBN 978-86-7607-091-6.

- Marcel Dunan (1917). L'été bulgare: notes d'un témoin, juillet-octobre 1915. Chapelot. pp. 162–.

- Documents diplomatiques français 2003, p. 804.

Bibliography

- Robert L. Jarman (1997). Yugoslavia: 1927-1937. Archive Editions Limited. ISBN 978-1-85207-950-5.

- Andrej Mitrović (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914-1918. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4.

- F.H. Hinsley; Keith Wilson (2016). Decisions For War, 1914. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-21310-8.

- Branislav Gligorijević (2002). King Alexander Karađorđević: In European politics (in Serbian). Institute for textbooks and teaching material.

- Foreign Office (2008). Documents on the foreign policy of the Kingdom of Serbia (in Serbian). Vol. 2. Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

- Čedomir Popov; Dragoljub Živojinović (2013). Two Centuries of Modern Serbian Diplomacy (in Serbian). Balkan Institute SANU. ISBN 978-86-7179-079-6.

- Ljubinka Trgovčević (2003). Students from Serbia in European universities in the 19th century (in Serbian). Historical Institute. ISBN 9788677430405.

- Auguste Boppe (1916). Revue Des Deux Mondes, 1916, Vol. 34, 1915 — 1916 (in French). Revue Limited. ISBN 978-0-260-79909-8.

- Institute of Historical Research, B.I.B.; Rudić, S.; Milkić, M. (2015). First World War, Serbia, the Balkans and the Great Powers. Institute of Historical Research. ISBN 978-86-7743-111-2.

- Rudić, S.; Denda, D.; Đurić, Đ.; Istorijski institut, B.; Matica srpska, N.S. (2018). The Volunteers in the Great War 1914-1918. Institute of Historical Research. ISBN 978-86-7743-129-7.

- Documents diplomatiques français (in French). P.I.E.-Peter Lang. 2003. ISBN 978-90-5201-111-0.