Nice

Nice (/niːs/ NEESS, French pronunciation: [nis] ⓘ; Niçard: Niça, classical norm, or Nissa, nonstandard, pronounced [ˈnisa]; Italian: Nizza [ˈnittsa]; Ligurian: Nissa; Ancient Greek: Νίκαια; Latin: Nicaea) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one million[4][3] on an area of 744 km2 (287 sq mi).[3] Located on the French Riviera, the southeastern coast of France on the Mediterranean Sea, at the foot of the French Alps, Nice is the second-largest French city on the Mediterranean coast and second-largest city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region after Marseille. Nice is approximately 13 kilometres (8 mi) from the principality of Monaco and 30 kilometres (19 mi) from the French–Italian border. Nice's airport serves as a gateway to the region.

Nice

Niça (Occitan) | |

|---|---|

Prefecture and commune | |

The city of Nice and several of its landmarks | |

Flag | |

| Motto(s): Nicæa civitas fidelissima (Latin: Nice, most loyal city) | |

Location of Nice | |

Nice  Nice | |

| Coordinates: 43°42′12″N 7°15′59″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur |

| Department | Alpes-Maritimes |

| Arrondissement | Nice |

| Canton | Nice-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 |

| Intercommunality | Métropole Nice Côte d'Azur |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2026) | Christian Estrosi[1] (LR) |

| Area 1 | 71.92 km2 (27.77 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 743.6 km2 (287.1 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,073 km2 (800 sq mi) |

| Population | 343,477 |

| • Rank | 5th in France |

| • Density | 4,800/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban (2018[3]) | 944,321 |

| • Urban density | 1,300/km2 (3,300/sq mi) |

| • Metro (2018[3]) | 609,695 |

| • Metro density | 290/km2 (760/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Niçois (m) Niçoise (f) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 06088 / |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Nice, Winter Resort Town of the Riviera |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii |

| Reference | 1635 |

| Inscription | 2021 (44th Session) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

The city is nicknamed Nice la Belle (Nissa La Bella in Niçard), meaning 'Nice the Beautiful', which is also the title of the unofficial anthem of Nice, written by Menica Rondelly in 1912. The area of today's Nice contains Terra Amata, an archaeological site which displays evidence of a very early use of fire 380,000 years ago. Around 350 BC, Greeks of Marseille founded a permanent settlement and called it Νίκαια, Nikaia, after Nike, the goddess of victory.[5] Through the ages, the town has changed hands many times. Its strategic location and port significantly contributed to its maritime strength. From 1388 it was a dominion of Savoy, then became part of the French First Republic between 1792 and 1815, when it was returned to the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, the legal predecessor of the Kingdom of Italy, until its re-annexation by France in 1860.

The natural environment of the Nice area and its mild Mediterranean climate came to the attention of the English upper classes in the second half of the 18th century, when an increasing number of aristocratic families began spending their winters there. In 1931, following its refurbishment, the city's main seaside promenade, the Promenade des Anglais ("Walkway of the English"), was inaugurated by Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught; it owes its name to visitors to the resort.[6] These included Queen Victoria along with her son Edward VII who spent winters there, as well as Henry Cavendish, born in Nice, who discovered hydrogen.

The clear air and soft light have particularly appealed to notable painters, such as Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse, Niki de Saint Phalle and Arman. Their work is commemorated in many of the city's museums, including Musée Marc Chagall, Musée Matisse and Musée des Beaux-Arts.[7] International writers have also been attracted and inspired by the city. Frank Harris wrote several books including his autobiography My Life and Loves in Nice. Friedrich Nietzsche spent six consecutive winters in Nice, and wrote Thus Spoke Zarathustra here. Additionally, Russian writer Anton Chekhov completed his play Three Sisters while living in Nice.

Nice's appeal extended to the Russian upper classes. Prince Nicholas Alexandrovich, heir apparent to Imperial Russia, died in Nice and was a patron of the Russian Orthodox Cemetery, Nice where Princess Catherine Dolgorukova, morganatic wife of the Tsar Alexander II of Russia, is buried. Also buried there are General Dmitry Shcherbachev and General Nikolai Yudenich, leaders of the anti-Communist White Movement.

Those interred at the Cimetière du Château include celebrated jeweler Alfred Van Cleef, Emil Jellinek-Mercedes, founder of the Mercedes car company, film director Louis Feuillade, poet Agathe-Sophie Sasserno, dancer Carolina Otero, Asterix comics creator René Goscinny, The Phantom of the Opera author Gaston Leroux, French prime minister Léon Gambetta, and the first president of the International Court of Justice José Gustavo Guerrero.

Because of its historical importance as a winter resort town for the European aristocracy and the resulting mix of cultures found in the city, UNESCO proclaimed Nice a World Heritage Site in 2021.[8] The city has the second largest hotel capacity in the country,[9] and it is the second most visited metropolis in Metropolitan France, receiving four million tourists every year.[10] It also has the third busiest airport in France, after the two main Parisian ones.[11] It is the historical capital city of the County of Nice (French: Comté de Nice, Niçard: Countèa de Nissa).[12]

History

Foundation

The first known hominid settlements in the Nice area date back about 400,000 years (homo erectus);[13] the Terra Amata archeological site shows one of the earliest uses of fire, construction of houses, as well as flint findings dated to around 230,000 years ago.[14] Nice was probably founded around 350 BC by colonists from the Greek city of Phocaea in western Anatolia. It was given the name of Níkaia (Νίκαια) in honour of a victory over the neighbouring Ligurians (people from the northwest of Italy, probably the Vediantii kingdom); Nike (Νίκη) was the Greek goddess of victory. The city soon became one of the busiest trading ports on the Ligurian coast; but it had an important rival in the Roman town of Cemenelum, which continued to exist as a separate city until the time of the Lombard invasions.[12] The ruins of Cemenelum are in Cimiez, now a district of Nice.

Early development

In the 7th century, Nice joined the Genoese League formed by the towns of Liguria. In 729 the city repulsed the Saracens; but in 859 and again in 880 the Saracens pillaged and burned it, and for most of the 10th century remained masters of the surrounding country.[12]

During the Middle Ages, Nice participated in the wars and history of Italy. As an ally of Pisa it was the enemy of Genoa, and both the King of France and the Holy Roman Emperor endeavoured to subjugate it; but in spite of this it maintained its municipal liberties. During the 13th and 14th centuries the city fell more than once into the hands of the Counts of Provence,[12] but it regained its independence even though related to Genoa.

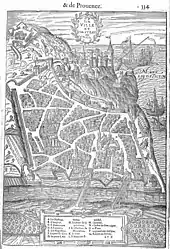

The medieval city walls surrounded the Old Town. The landward side was protected by the River Paillon, which was later covered over and is now the tram route towards the Acropolis. The east side of the town was protected by fortifications on Castle Hill. Another river flowed into the port on the east side of Castle Hill. Engravings suggest that the port area was also defended by walls. Under Monoprix in Place de Garibaldi are excavated remains of a well-defended city gate on the main road from Turin.

Duchy of Savoy

In 1388, the commune placed itself under the protection of the Counts of Savoy.[12] Nice participated – directly or indirectly – in the history of Savoy until 1860.

The maritime strength of Nice now rapidly increased until it was able to cope with the Barbary pirates; the fortifications were largely extended and the roads to the city improved.[12] In 1561 Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy abolished the use of Latin as an administrative language and established the Italian language as the official language of government affairs in Nice.

During the struggle between Francis I and Charles V great damage was caused by the passage of the armies invading Provence; pestilence and famine raged in the city for several years.[12] In 1538, in the nearby town of Villeneuve-Loubet, through the mediation of Pope Paul III, the two monarchs concluded a ten years' truce.[15]

In 1543, Nice was attacked by the united Franco-Ottoman forces of Francis I and Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha, in the Siege of Nice; though the inhabitants repulsed the assault which followed the terrible bombardment, they were ultimately compelled to surrender, and Barbarossa was allowed to pillage the city and to carry off 2,500 captives. Pestilence appeared again in 1550 and 1580.[12]

In 1600, Nice was briefly taken by the Duke of Guise. By opening the ports of the county to all nations, and proclaiming full freedom of trade (1626), the commerce of the city was given great stimulus, the noble families taking part in its mercantile enterprises.[12]

Captured by Nicolas Catinat in 1691, Nice was restored to Savoy in 1696; but it was again besieged by the French in 1705, and in the following year its citadel and ramparts were demolished.[12]

Kingdom of Sardinia

The Treaty of Utrecht (1713) once more gave the city back to the Duke of Savoy, who was on that same occasion recognised as King of Sicily. In the peaceful years which followed, the "new town" was built. From 1744 until the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) the French and Spaniards were again in possession.

In 1775 the king, who in 1718 had swapped his sovereignty of Sicily for the Kingdom of Sardinia, destroyed all that remained of the ancient liberties of the commune. Conquered in 1792 by the armies of the First French Republic, the County of Nice continued to be part of France until 1814; but after that date it reverted to the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia.[12]

.tiff.jpg.webp)

French annexation

After the Treaty of Turin was signed in 1860 between the Sardinian king and Napoleon III as a consequence of the Plombières Agreement, the county was again and definitively ceded to France as a territorial reward for French assistance in the Second Italian War of Independence against Austria, which saw Lombardy united with Piedmont-Sardinia. King Victor-Emmanuel II, on 1 April 1860, solemnly asked the population to accept the change of sovereignty, in the name of Italian unity, and the cession was ratified by a regional referendum. Italophile manifestations and the acclamation of an "Italian Nice" by the crowd are reported on this occasion.[16] A plebiscite was voted on 15 and 16 April 1860. The opponents of annexation called for abstention, hence the very high abstention rate. The "yes" vote won 83% of registered voters throughout the county of Nice and 86% in Nice, partly thanks to pressure from the authorities.[5] This is the result of a masterful operation of information control by the French and Piedmontese governments, in order to influence the outcome of the vote in relation to the decisions already taken.[17] The irregularities in the plebiscite voting operations were evident. The case of Levens is emblematic: the same official sources recorded, faced with only 407 voters, 481 votes cast, naturally almost all in favor of joining France.[18]

The Italian language that was the official language of the County, used by the Church, at the town hall, taught in schools, used in theaters and at the Opera, was immediately abolished and replaced by French.[19][20] Discontent over annexation to France led to the emigration of a large part of the Italophile population, also accelerated by Italian unification after 1861. A quarter of the population of Nice, around 11,000 people from Nice, decided to voluntarily exile to Italy.[21][22] The emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy took the name of Niçard exodus. Many Italians from Nizza then moved to the Ligurian towns of Ventimiglia, Bordighera and Ospedaletti,[23] giving rise to a local branch of the movement of the Italian irredentists which considered the re-acquisition of Nice to be one of their nationalist goals. Giuseppe Garibaldi, born in Nice, strongly opposed the cession to France, arguing that the ballot was rigged by the French. Furthermore, for the niçard general his hometown was unquestionably Italian. Politically, the liberals of Nice and the partisans of Garibaldi also appreciated very little Napoleonic authoritarianism. Elements on the right (aristocrats) as on the left (Garibaldians) therefore wanted Nice to return to Italy. Savoy was also transferred to the French crown by similar means.

In 1871, during the first free elections in the County, the pro-Italian lists obtained almost all the votes in the legislative elections (26,534 votes out of 29,428 votes cast), and Garibaldi was elected deputy at the National Assembly. Pro-Italians took to the streets cheering "Viva Nizza! Viva Garibaldi!". The French government sent 10,000 soldiers to Nice, closed the Italian newspaper Il Diritto di Nizza and imprisoned several demonstrators. The population of Nice rose up from 8 to 10 February and the three days of demonstration took the name of "Niçard Vespers". The revolt was suppressed by French troops. On 13 February, Garibaldi was not allowed to speak at the French parliament meeting in Bordeaux to ask for the reunification of Nice to the newborn Italian unitary state, and he resigned from his post as deputy.[24] The failure of Vespers led to the expulsion of the last pro-Italian intellectuals from Nice, such as Luciano Mereu or Giuseppe Bres, who were expelled or deported.

The pro-Italian irredentist movement persisted throughout the period 1860–1914, despite the repression carried out since the annexation. The French government implemented a policy of Francization of society, language and culture.[25] The toponyms of the communes of the ancient County have been francized, which acted as a bank to the obligation to use French in Nice,[26] as well as certain surnames (for example the Italian surname "Bianchi" was francized into "Leblanc", and the Italian surname "Del Ponte" was francized into "Dupont").[27]

Italian-language newspapers in Nice were banned. In 1861, La Voce di Nizza was closed (temporarily reopened during the Niçard Vespers), followed by Il Diritto di Nizza, closed in 1871.[24] In 1895 it was the turn of Il Pensiero di Nizza, accused of irredentism. Many journalists and writers from Nice wrote in these newspapers in Italian. Among these are Enrico Sappia, Giuseppe André, Giuseppe Bres, Eugenio Cais di Pierlas and others.

20th century

In 1900, the Tramway de Nice electrified its horse-drawn streetcars and spread its network to the entire département from Menton to Cagnes-sur-Mer. By the 1930s more bus connections were added in the area. In the 1930s, Nice hosted international car racing in the Formula Libre (predecessor to Formula One) on the so-called Circuit Nice. The circuit started along the waterfront just south of the Jardin Albert I, then headed westward along the Promenade des Anglais followed by a hairpin turn at the Hotel Negresco to come back eastward and around the Jardin Albert I before heading again east along the beach on the Quai des Etats-Unis.[28]

As war broke out in September 1939, Nice became a city of refuge for many displaced foreigners, notably Jews fleeing the Nazi progression into Eastern Europe. From Nice many sought further shelter in the French colonies, Morocco and North and South America. After July 1940 and the establishment of the Vichy Regime, antisemitic aggressions accelerated the exodus, starting in July 1941 and continuing through 1942. On 26 August 1942, 655 Jews of foreign origin were rounded up by the Laval government and interned in the Auvare barracks. Of these, 560 were deported to Drancy internment camp on 31 August 1942. Due to the activity of the Jewish banker Angelo Donati and of the Capuchin friar Père Marie-Benoît the local authorities hindered the application of anti-Jewish Vichy laws.[29]

The first résistants to the new regime were a group of high school seniors of the Lycée de Nice, now Lycée Masséna, in September 1940, later arrested and executed in 1944 near Castellane. The first public demonstrations occurred on 14 July 1942 when several hundred protesters took to the streets along the Avenue de la Victoire and in the Place Masséna. In November 1942 German troops moved into most of unoccupied France, but Italian troops moved into a smaller zone including Nice. A certain ambivalence remained among the population, many of whom were recent immigrants of Italian ancestry. However, the resistance gained momentum after the Italian surrender in 1943 when the German army occupied the former Italian zone. Reprisals intensified between December 1943 and July 1944, when many partisans were tortured and executed by the local Gestapo and the French Milice. American paratroopers entered the city on 30 August 1944 and Nice was finally liberated. The consequences of the war were heavy: the population decreased by 15% and economic life was totally disrupted.

In the second half of the 20th century, Nice enjoyed an economic boom primarily driven by tourism and construction. Two men dominated this period: Jean Médecin, mayor for 33 years from 1928 to 1943 and from 1947 to 1965, and his son Jacques, mayor for 24 years from 1966 to 1990. Under their leadership, there was extensive urban renewal, including many new constructions. These included the convention centre, theatres, new thoroughfares and expressways. The arrival of the Pieds-Noirs, refugees from Algeria after 1962 independence, also gave the city a boost and somewhat changed the make-up of its population and traditional views. By the late 1980s, rumors of political corruption in the city government surfaced; and eventually formal accusations against Jacques Médecin forced him to flee France in 1990. Later arrested in Uruguay in 1993, he was extradited back to France in 1994, convicted of several counts of corruption and associated crimes and sentenced to imprisonment.

On 16 October 1979, a landslide and an undersea slide caused two tsunamis that hit the western coast of Nice; these events killed between 8 and 23 people.

21st century

In February 2001, European leaders met in Nice to negotiate and sign what is now the Treaty of Nice, amending the institutions of the European Union.[30]

In 2003, local Chief Prosecutor Éric de Montgolfier alleged that some judicial cases involving local personalities had been suspiciously derailed by the local judiciary, which he suspected of having unhealthy contacts through Masonic lodges with the defendants. A controversial official report stated later that Montgolfier had made unwarranted accusations.

On 14 July 2016, a truck was deliberately driven into a crowd of people by Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel on the Promenade des Anglais. The crowd was watching a fireworks display in celebration of Bastille Day.[31] A total of 87 people were killed, including the perpetrator, who was shot dead by police.[32][33] Another 434 were injured, with 52 in critical care and 25 in intensive care, according to the Paris prosecutor.[34] On 29 October 2020, a stabbing attack killed three people at the local Notre-Dame de Nice. One of the victims, a woman, was beheaded by the attacker.[35] Several additional victims were injured. The attacker, who was shot by the police, was taken into custody. The Islamic state claimed responsibility for both attacks.[36]

In 2021, the city was proclaimed a World Heritage Site by UNESCO as "Nice, Winter Resort Town of the Riviera".[8]

Architecture

The Promenade des Anglais ("Promenade of the English") is a promenade along the Baie des Anges ("Bay of the Angels"), which is a bay of the Mediterranean in Nice. Before Nice was urbanised, the coastline at Nice was just bordered by a deserted stretch of shingle beach (covered with large pebbles). The first houses were located on higher ground well away from the sea, as wealthy tourists visiting Nice in the 18th century did not come for the beach, but for the gentle winter weather. The areas close to the water were home to Nice's dockworkers and fishermen.

In the second half of the 18th century, many wealthy English people took to spending the winter in Nice, enjoying the panorama along the coast. This early aristocratic English colony conceived the building of a promenade with the leadership and financial support of Rev. Lewis Way.[37] With the initial promenade completed, the city of Nice, intrigued by the prospect, greatly increased the scope of the work. The Promenade was first called the Camin dei Anglès (the English Way) by the Niçois in their native dialect Nissart. In 1823, the promenade was named La Promenade des Anglais by the French, a name that would stick after the annexation of Nice by France in 1860.[38]

The Hotel Negresco on the Promenade des Anglais was named after Henri Negresco who had the palatial hotel constructed in 1912. In keeping with the conventions of the time, when the Negresco first opened in 1913 its front opened on the side opposite the Mediterranean.

Another place worth mentioning is the small street parallel to the Promenade des Anglais, leading from Nice's downtown, beginning at Place Masséna and running parallel to the promenade in the direction of the airport for a short distance of about 4 blocks. This section of the city is referred to as the "Zone Pietonne", or "Pedestrian Zone". Cars are not allowed (with exception to delivery trucks), making this avenue a popular walkway.

Old Nice is also home to the Opéra de Nice. It was constructed at the end of the 19th century under the design of François Aune, to replace King Charles Félix's Maccarani Theater. Today, it is open to the public and provides a regular program of performances.

Other sights include:

- Palais communal de Nice

- Palais de la Méditerranée

- Palais de l'agriculture

- Gare du Sud

- Jardin Albert-Ier

- Castle of Nice

Religious buildings

Religious buildings in the city include:

- Nice Cathedral

- Notre-Dame de Nice

- Russian Orthodox Cathedral, Nice

- Église Notre-Dame-du-Port de Nice

- Church of Gesù, Nice

Museums

- Musée Masséna

- Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nice

- Musée Matisse

- Musée Marc Chagall

Place Masséna

The Place Masséna is the main square of the city. Before the Paillon River was covered over, the Pont-Neuf was the only practicable way between the old town and the modern one. The square was thus divided into two parts (North and South) in 1824. With the demolition of the Masséna Casino in 1979, the Place Masséna became more spacious and less dense and is now bordered by red ochre buildings of Italian architecture.

The recent rebuilding of the tramline gave the square back to the pedestrians, restoring its status as a real Mediterranean square. It is lined with palm trees and stone pines, instead of being the rectangular roundabout of sorts it had become over the years. Since its construction, the Place Masséna has always been the spot for great public events. It is used for concerts, and particularly during the summer festivals, the Corso carnavalesque (carnival parade) in February, the military procession of 14 July (Bastille Day) or other traditional celebrations and banquets.

The Place Masséna is a two-minute walk from the Promenade des Anglais, old town, town centre, and Albert I Garden (Jardin Albert Ier). It is also a large crossroads between several of the main streets of the city: avenue Jean Médecin, avenue Félix Faure, boulevard Jean Jaurès, avenue de Verdun and rue Gioffredo.

View of the Place Masséna

View of the Place Masséna Place Masséna by night, 2012

Place Masséna by night, 2012

Place Garibaldi

The Place Garibaldi also stands out for its architecture and history. It is named after Giuseppe Garibaldi, hero of the Italian unification (born in Nice in 1807 when Nice was part of the Napoleonic Empire, before reverting to the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia). The square was built at the end of the 18th century and served as the entry gate to the city and end of the road from Turin. It took several names between 1780 and 1870 (Plaça Pairoulièra, Place de la République, Place Napoléon, Place d'Armes, Place Saint-Augustin, Piazza Vittorio) and finally Place Garibaldi in September 1870.

A statue of Garibaldi, who was fiercely in favour of the union of Nice with Italy, stands in the centre of the square. The recent rebuilding of the area to accommodate the new tramway line gave mostly the entire square to pedestrians. The architecture is in line with the Turin model, which was the norm of urban renewal throughout the entire realm of the House of Savoy.

It is a crossroads between the Vieux Nice (old town) and the town centre. Place Garibaldi is close to the eastern districts of Nice, Port Lympia (Lympia Harbour), and the TNL commercial centre. This square is also a junction of several important streets: the boulevard Jean-Jaurès, the avenue de la République, the rue Cassini and the rue Catherine-Ségurane.

Place Rossetti

Entirely enclosed and pedestrianised, this square is located in the heart of the old town. With typical buildings in red and yellow ochres surrounding the square, the cathédrale Sainte-Réparate and the fountain in the centre, place Rossetti is a must-see spot in the old town. By day, the place is invaded by the terraces of traditional restaurants and the finest ice-cream makers. By night, the environment changes radically, with tourists and youths flocking to the square, where music reverberates on the walls of the small square. The square's lighting at night gives it a magical aspect.

Place Rossetti is in the centre of the old town, streets Jesus, Rossetti, Mascoïnat and the Pont-vieux (old bridge)

Cours Saleya

The Cours Saleya is situated parallel to the Quai des États-Unis. In the past, it belonged to the upper classes. It is probably the most traditional square of the town, with its daily flower market. The Cours Saleya also opens on the Palais des Rois Sardes (Palace of the Kings of Sardinia). In the present, the court is mostly a place of entertainment.

Place du Palais

As its name indicates, the Place du Palais is where the Palais de la Justice (Law courts) of Nice is located. On this square, there also is the Palais Rusca, which also belongs to the justice department (home of the tribunal de grande instance).

The square is also notable due to the presence of the city clock. Today, the Place du Palais is alive day and night. Often, groups of youths will hang out on the steps leading to the Palais de la Justice. Concerts, films, and other major public events frequently occur in this space.

It is situated halfway between the Cours Saleya and Place Masséna.

Administration

Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, Nice is a commune and the prefecture (administrative capital) of the Alpes-Maritimes département. However, it is also the largest city in France that is not a regional capital; the much larger Marseille is its regional capital. Christian Estrosi, its mayor, is a member of the Republicans (formerly the Union for a Popular Movement), the party supporting former President Nicolas Sarkozy.

The city is divided into nine cantons: Nice-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

Coat of arms

The coat of arms of Nice appeared for the first time in a copy of the Regulations of Amadeus VIII, probably written around 1430.[39] The Nice is symbolised by a red eagle on silver background, placed on three mountains, which can be described in French heraldic language as "d'argent à une aigle de gueule posée sur trois coupeaux".[39] ("Upon silver a red eagle is displayed, posed upon three mounds.") The arms have only undergone minor changes: the eagle has become more and more stylised, it now "wears" a coronet for the County of Nice, and the three mountains are now surrounded by a stylised sea.[39]

The presence of the eagle, an imperial emblem, shows that these arms are related to the power of the House of Savoy. The eagle standing over the three hills is a depiction of Savoy, referring to its domination over the country around Nice.[39] The combination of silver and red (argent and gules) is a reference to the colours of the flag of Savoy.[39] The three mountains symbolise a territorial honour, without concern for geographic realism.[39]

Geography

Nice consists of two large bays. Villefranche-sur-Mer sits on an enclosed bay, while the main expanse of the city lies between the old port city and the Aeroport de Côte d'Azur, across a gently curving bay. The city rises from the flat beach into gentle rising hills, then is bounded by surrounding mountains that represent the Southern and nearly the Western extent of the Ligurian Alps range.

Flora

The natural vegetation of Nice is typical for a Mediterranean landscape, with a heavy representation of broadleaf evergreen shrubs. Trees tend to be scattered but form dense forests in some areas. Large native tree species include evergreens such as holm oak, stone pine and arbutus. Many introduced species grow in parks and gardens. Palms, eucalyptus and citrus fruits are among the trees which give Nice a subtropical appearance. But there are also species familiar to temperate areas around the world; examples include horse chestnut, linden and even Norway spruce.

Climate

Nice has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa), enjoying mild winters with moderate rainfall. It is one of the warmest Mediterranean climates for its latitude. Summers are warm to hot, dry, and sunny. Rainfall is rare in this season, and a typical July month only records one or two days with measurable rainfall. The temperature is typically above 26 °C (79 °F) but rarely above 32 °C (90 °F). The climate data is recorded from the airport, located just metres from the sea. Summer temperatures, therefore, are often higher in the city. The average maximum temperature in the warmest months of July and August is about 27 °C (81 °F). The highest recorded temperature was 37.7 °C (99.9 °F) on 1 August 2006. Autumn generally starts sunny in September and becomes more cloudy and rainy towards October, while temperatures usually remain above 20 °C (68 °F) until November where days start to cool down to around 17 °C (63 °F).

Winters are characterised by mild days (11 to 17 °C (52 to 63 °F)), cool nights (4 to 9 °C (39 to 48 °F)), and variable weather. Days can be either sunny and dry or damp and rainy. The average minimum temperature in January is around 5 °C (41 °F). Frost is unusual and snowfalls are rare. The most recent snowfall in Nice was on 26 February 2018.[40] Nice also received a dusting of snow in 2005, 2009 and 2010. Spring starts cool and rainy in late March, and Nice becomes increasingly warm and sunny around June.

| Climate data for Nice (Nice Côte d'Azur Airport), elevation: 4 m or 13 ft, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1942–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.5 (72.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

36.8 (98.2) |

37.0 (98.6) |

37.7 (99.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

29.9 (85.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

37.7 (99.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.9 (82.2) |

24.8 (76.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

19.8 (67.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.5 (49.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.5 (76.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

10.3 (50.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.8 (42.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

20.8 (69.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

14.0 (57.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

2.9 (37.2) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.7 (53.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

4.2 (39.6) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 73.5 (2.89) |

53.6 (2.11) |

51.0 (2.01) |

68.8 (2.71) |

40.3 (1.59) |

35.7 (1.41) |

13.6 (0.54) |

17.2 (0.68) |

81.0 (3.19) |

127.9 (5.04) |

138.4 (5.45) |

90.3 (3.56) |

791.3 (31.15) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.8 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 6.4 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 4.9 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 6.0 | 62.1 |

| Average snowy days | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 156.7 | 166.1 | 218.0 | 229.2 | 270.9 | 309.8 | 349.3 | 323.2 | 249.8 | 191.1 | 151.5 | 145.2 | 2,760.5 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: Météo-France[41] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[42] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Nice (Nice Côte d'Azur Airport), elevation: 4 m or 13 ft, 1961–1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.6 (67.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.2 (77.4) |

30.3 (86.5) |

31.1 (88.0) |

35.7 (96.3) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

29.9 (85.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

21.3 (70.3) |

35.7 (96.3) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 14.7 (58.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.1 (64.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.4 (83.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.6 (54.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

23.1 (73.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

24.3 (75.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

19.0 (66.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.8 (67.6) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.1 (73.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

15.3 (59.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

5.7 (42.3) |

11.7 (53.0) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

4.1 (39.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

3.2 (37.8) |

2.1 (35.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

2.9 (37.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

7.6 (45.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 61.3 (2.41) |

50.8 (2.00) |

66.2 (2.61) |

57.0 (2.24) |

37.4 (1.47) |

30.8 (1.21) |

6.5 (0.26) |

24.5 (0.96) |

29.5 (1.16) |

78.9 (3.11) |

91.5 (3.60) |

67.1 (2.64) |

601.5 (23.67) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.8 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 4.1 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 5.8 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 62.7 |

| Average snowy days | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67 | 68 | 69 | 72 | 75 | 75 | 73 | 72 | 74 | 73 | 71 | 67 | 71.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 150.3 | 151.9 | 202.3 | 226.9 | 269.8 | 295.7 | 340.4 | 306.8 | 238.7 | 205.0 | 155.5 | 150.9 | 2,694.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 53 | 52 | 55 | 57 | 60 | 65 | 74 | 72 | 64 | 61 | 55 | 55 | 60 |

| Source 1: NOAA[43] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity)[44] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Nice | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 13.4 (56.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.6 (67.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.9 (64.3) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 9.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[42] | |||||||||||||

Economy and tourism

Nice is the seat of the Chambre de commerce et d'industrie Nice Côte d'Azur, which manages the Port of Nice. Investors from France and abroad can benefit from the assistance of the Côte d'Azur Economic Development Agency Team Côte d'Azur.

Nice has one conference centre: the Palais des Congrès Acropolis. The city also has several business parks, including l'Arenas, Nice the Plain, Nice Méridia, Saint Isidore, and the Northern Forum.

In addition, the city features several shopping centres such as Nicetoile on Avenue Jean Médecin, Cap3000 in Saint-Laurent-du-Var (the 5th-biggest mall in France by surface area), Nice TNL, Nice Lingostière, Northern Forum, St-Isidore, the Trinity (around the Auchan hypermarket) and Polygone Riviera in Cagnes-sur-Mer.

Sophia Antipolis is a technology park northwest of Antibes. Much of the park is within the commune of Valbonne. Established between 1970 and 1984, it primarily houses companies in the fields of computing, electronics, pharmacology and biotechnology. Several institutions of higher learning are also located here, along with the European headquarters of W3C. It is known as "Europe's first science and technology hub" and is valued at more than 5 billion euros.[45]

The Nice metropolitan area had a GDP amounting to $47.7 billion, and $34,480 per capita,[46] slightly lower than the French average.

Transport

Port

The main port of Nice is also known as Lympia port. This name comes from the Lympia spring which fed a small lake in a marshy zone where work on the port was started in 1745. Today this is the principal harbour installation of Nice – there is also a small port in the Carras district. The port is the first port cement manufacturer in France, linked to the treatment plants of the rollers of the valley of Paillon. Fishing activities remain but the number of professional fishermen is now less than 10. Nice, being the point of continental France nearest to Corsica, has ferry connections with the island developed with the arrival of NGV (navires à grande vitesse) or high-speed craft. The connections are provided by Corsica Ferries - Sardinia Ferries. Located in front of the port, the Place Cassini has been renamed Place of Corsica.

Airport

Nice Côte d'Azur Airport is the third busiest airport in France after Charles de Gaulle Airport and Orly Airport, both near Paris. It is on the Promenade des Anglais, near l'Arénas and has two terminals. Due to its proximity to the Principality of Monaco, it also serves as that city–state's airport. A helicopter service provided by Heli Air Monaco and Monacair links the city and airport. It is run by the ACA (Aéroports Côte d'Azur), which includes Cannes - Mandelieu Airport and La Môle – Saint-Tropez Airport. Public transportation into the city proper is serviced by the Tramway line 2 (T2).

Rail

The main railway station is Nice-Ville, served both by high-speed TGV trains connecting Paris and Nice in less than 6 hours and by local commuter TER services. Marseille is reached in 2.5 hours. Nice also has international connections to Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, and Russia.[47] Nice is also served by several suburban stations including Nice St-Augustin, Nice St-Roch and Nice Riquier.

Nice is also the southern terminus of the independently run Chemins de Fer de Provence railway line which connects the city with Digne in approximately 4 hours from the Nice CP station. A metro-like suburban service is also provided on the southern part of the line.

Tram

Tramway de Nice began operating horse-drawn trams in 1879. Electrified in 1900, the combined length of the network reached 144 km (89+1⁄2 mi) by 1930. The replacement of trams with trolleybuses began in 1948 and was completed in 1953.

In 2007, the new Tramway de Nice linked the northern and eastern suburbs via the city centre. Two other lines are currently operating. The second line runs east–west from Jean Médecin to the Nice Côte d'Azur Airport and reaches the Port, while the third line provides a connection to the future TGV Nice Saint-Augustin and to Lingostière railway station.[48] A fourth line is set to run from the future TGV Nice Saint-Augustin to Cagnes-sur-Mer.

Road

The A8 autoroute and the Route nationale 7 pass through the Nice agglomeration.

Sports and entertainment

Sport

- The city's major football club is OGC Nice. They play in Ligue 1 (the top division in France).

- The Olympic Nice swimming club (French: Olympic Nice Natation) is also notable; Camille Muffat and Yannick Agnel trained there.[49]

- Nice hosts the finish of the annual cycling race Paris–Nice.

- The Nice Hockey Élite club play in Ligue Magnus, the top men's division of the French ice hockey pyramid.

- The Stade Niçois is a rugby club playing in Fédérale 1.

Population

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: EHESS[50] and INSEE[51] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As of 2018, the urban area (unité urbaine) of Nice, defined by INSEE, is home to 944,321 inhabitants (seventh most populous in France) and its metropolitan area (aire urbaine) totals 609,695 inhabitants, which makes it the 13th largest in France.[3] Part of the urban area of Nice belongs to the metropolitan area of Cannes–Antibes.

Since the 1970s, the number of inhabitants has not changed significantly; the relatively high migration to Nice is balanced by a natural negative growth of the population.

Observatory

The Observatoire de Nice (Nice Observatory) is located on the summit of Mont Gros. The observatory was established in 1879 by the banker Raphaël Bischoffsheim. The architect was Charles Garnier; Gustave Eiffel designed the main dome.

The 76-cm (30-inch) refractor telescope that became operational in 1888 was at that time the world's largest telescope.

Culture

Terra-Amata, an archaeological site dating from the Lower Palaeolithic age, is situated near Nice. Nice itself was established by the ancient Greeks. There was also an independent Roman city, Cemenelum, near Nice, where the hill of Cimiez is located.

Since the 2nd century AD, the light of the city has attracted painters and sculptors such as Chagall, Matisse, Niki de Saint Phalle, Klein, Arman and Sosno. Nice inspired many composers and intellectuals in different countries e.g. Berlioz, Rossini, Nietzsche, etc.

Nice also has numerous museums of all kinds: Musée Marc Chagall, Musée Matisse, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Musée international d'Art naïf Anatole Jakovsky, Musée Terra-Amata, Museum of Asian Art, Musée d'art moderne et d'art contemporain (which devotes much space to the well-known École of Nice "), Museum of Natural History, Musée Masséna, Naval Museum and Galerie des Ponchettes.

Being a vacation resort, Nice hosts many festivals throughout the year, such as the Nice Carnival and the Nice Jazz Festival.

Nice has a distinct culture due to its unique history. The local language Niçard (Nissart) is an Occitan dialect (but some Italian scholars argue that it is a Ligurian dialect). It is still spoken by a substantial minority. Strong Italian and (to a lesser extent) Corsican influences make it more intelligible to speakers of Italian than other extant Provençal dialects.

In the past, Nice has welcomed many immigrants from Italy (who continue to make up a large proportion of the population), as well as Spanish and Portuguese immigrants. However, in the past few decades immigration has been opened to include immigrants from all over the world, particularly those from former Northern and Western African colonies, as well as Southeast Asia. Traditions are still alive, especially in folk music and dances, including the farandole – an open-chain community dance.

Since 1860 a cannon (based at the Château east of Old Nice) is shot at twelve o'clock sharp. The detonation can be heard almost all over the city. This tradition goes back to Sir Thomas Coventry, who intended to remind the citizens of having lunch on time.[52]

Cuisine

The cuisine of Nice is especially close to those of Provence but also Liguria and Piedmont and uses local ingredients (olive oil, anchovies, fruit and vegetables) but also those from more remote regions, in particular from Northern Europe, because ships which came to pick up olive oil arrived full of food products, such as dried haddock.

The local cuisine is rich in around 200 recipes. Most famous include the local tart made with onions and anchovies (or anchovy paste), named "Pissaladière" and derived from the ligurian pissalandrea, a sort of pizza. Socca is a type of pancake made from chickpea flour. Farcis niçois is a dish made from vegetables stuffed with a mixture of breadcrumbs, meat (generally sausage and ground beef), and herbs; and salade niçoise is a tomato salad with baked eggs, tuna or anchovies, olives and often lettuce. Green peppers, vinaigrette, and other raw green vegetables may be included. Potatoes and green beans are not traditional components.

Local meat comes from neighbouring valleys, such as the sheep of Sisteron. Local fish, such as mullets, bream, sea urchins, anchovies and poutine/gianchetti are used to a great extent, so much so that it has given birth to a proverb: "fish are born in the sea and die in oil".[53]

Examples of Niçois specialties include:

Education

International relations

Alicante, Spain

Alicante, Spain Antananarivo, Madagascar

Antananarivo, Madagascar Astana, Kazakhstan[55]

Astana, Kazakhstan[55] Can Tho, Vietnam

Can Tho, Vietnam Cartagena, Colombia

Cartagena, Colombia Cuneo, Italy

Cuneo, Italy Edinburgh, UK[56][57]

Edinburgh, UK[56][57] Gdańsk, Poland

Gdańsk, Poland Hangzhou, China

Hangzhou, China Houston, United States

Houston, United States Kamakura, Japan

Kamakura, Japan.svg.png.webp) Laval, Canada

Laval, Canada Libreville, Gabon

Libreville, Gabon.svg.png.webp) Locarno, Switzerland[58]

Locarno, Switzerland[58] Louisiana (state), United States

Louisiana (state), United States Manila, Philippines

Manila, Philippines Miami, United States

Miami, United States Netanya, Israel[59]

Netanya, Israel[59] Nouméa, New Caledonia

Nouméa, New Caledonia Nuremberg, Germany

Nuremberg, Germany Papeete, France

Papeete, France Phuket, Thailand

Phuket, Thailand Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Saint-Denis, France

Saint-Denis, France Saint Petersburg, Russia

Saint Petersburg, Russia Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain

Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain Sorrento, Italy

Sorrento, Italy Szeged, Hungary

Szeged, Hungary Thessaloniki, Greece[60]

Thessaloniki, Greece[60] Xiamen, China

Xiamen, China

Yalta, Ukraine or Russia (disputed)

Yalta, Ukraine or Russia (disputed) Yerevan, Armenia[61]

Yerevan, Armenia[61]

Notable people

- Nicholas Alexandrovich – tsesarevich, the heir apparent, of Imperial Russia died in Nice and was patron of the Russian Orthodox Cemetery, Nice

- Louis Aragon – Poet and novelist and his wife, the Russian-born writer Elsa Triolet, lived clandestinely in Nice during World War II

- The Avener (born 1987) – musical artist and DJ, born in Nice

- Jean Behra (1921–1959) – racing driver, born in Nice

- Elliot Benchetrit (born 1998) – tennis player

- Freda Betti (1924–1979) – opera singer

- Henri Betti (1917–2005) – composer and pianist

- Priscilla Betti (born 1989) – singer and actress

- Jules Bianchi (1989–2015) – Formula 1 Driver

- Surya Bonaly (born 1973) – figure skater

- Alexy Bosetti (born 1993) – footballer

- Loïc Bruni (born 1994) professional downhill mountain biker

- Albert Calmette (1863–1933) – physician, bacteriologist and immunologist

- René Cassin – jurist, law professor and judge, former student of Nice's Lycée Massena, he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1968[62]

- Henry Cavendish – British scientist noted for his discovery of hydrogen

- Éric Ciotti (born 1965) – politician, born in Nice

- Alfred Van Cleef – jeweler buried in Nice at the Cimetière du Château

- Alizé Cornet (born 1990) – tennis player

- Marc Duret (born 1957) – French-American actor and director, starring in The Big Blue, La Femme Nikita, La haine, Borgia, Outlander, born in Nice

- Christian Estrosi (born 1955) – born in Nice, mayor from 2008 to 2016 and again since 2017

- Jacqueline Eymar (1922–2008) – classical pianist

- Feder (born 1987) – musical artist and DJ, born in Nice

- Léon Gambetta (1838–1881) – politician, buried in Nice

- Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882) – Italian general, politician and patriot, a founding father of Italy, born in Nice

- René Goscinny – Asterix creator, buried in Nice

- James C Harris – 19th century British consul at Nice; painted many scenes in and around the city

- José Gustavo Guerrero – first president of the International Court of Justice buried in Nice at Cimetière du Château

- Dominic Howard – drummer for Muse currently lives in Nice

- Cyprien Iov (born 1989) – known simply as Cyprien, comedian and actor with a large Youtube channel, born in Nice

- Dominique Jean-Zéphirin (born 1982) – footballer

- Emil Jellinek-Mercedes – General Counsel for Austria-Hungary, and founder of Mercedes car company buried in Nice at Cimetière du Château

- Elton John – singer, owned a house in Mont Boron on the hills of Nice

- David Kadouch (born 1985), pianist and chamber musician

- Alexis Kossenko (born 1977) – classical flautist and conductor

- Georges Lautner (1926–2013) – director born in Nice, buried in the cemetery of the Castle

- J. M. G. Le Clézio – author and professor, was awarded the 2008 Nobel Prize in Literature[63]

- Hugo Lloris (born 1986) – French international footballer, born in Nice

- Heinrich Mann – German novelist (and brother of Thomas Mann) lived in Nice

- André Masséna (1758–1817) – 1st Duc de Rivoli, 1st Prince d'Essling, one of the original 18 Marshals of the Empire, French military commander during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, his nickname was l'Enfant chéri de la Victoire ("the Dear Child of Victory")[64]

- Jean-Pierre Mocky (1929–2019) – film director, actor, screenwriter and producer

- Amedeo Modigliani lived for a few months in Nice with his companion Jeanne Hébuterne; she gave birth to their daughter Giovanna in 1918.

- Mohammed VI, king of Morocco, obtained the title of Doctor of Law at the University of Nice Sophia Antipolis

- Jacques Ochs (1883–1971) – artist and Olympic fencing champion

- Clairemarie Osta (born 1970) – ballet dancer, étoile at Paris Opera Ballet

- Pino Presti – Italian bassist, arranger, composer, conductor and record producer, lived in Nice[65]

- Fabio Quartararo (born 1999) – French MotoGP World Champion

- Auguste Renoir – had his studio in Nice from 1911 to 1919 at the corner of the Rue Alfred Mortier and the Quai St Jean Baptiste. A commemorative plaque is affixed to it.

- Dick Rivers – born Hervé Forneri, rock singer, born in Nice in 1945

- Ken Samaras (born 1990) – known as Nekfeu, french rapper, born in the suburbs of Nice

- Robert W. Service – poet and writer of the Klondike Gold Rush lived in Nice during the summers from 1916 to 1940[66]

- Joann Sfar – comics artist, comic book creator and film director

- Michel Siffre (born 1939) – adventurer and scientist

- Gilles Simon (born 1984) – tennis player

- Michael Sinterniklaas (born 1972) – American voice actor

- Aimé Teisseire (1914–2008) – French Army officer, lived in Nice after his retirement from the military until his death at the age of 93[67]

- Simone Veil (1927–2017) – lawyer and politician who served as Minister of Health, President of the European Parliament and member of the Constitutional Council of France; survivor of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, born in Nice

- Queen Victoria – Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Empress of India, stayed many winters in Nice

- Valérie Zenatti (born 1970) – writer

- Nguyễn Văn Xuân (1892–1989), French Army general and Vietnamese politician, lived in France in later life until he died in Nice at the age of 96

Honorary citizens

Charles III, then Prince of Wales, received honorary citizenship of Nice on 8 May 2018.[68]

See also

References

- "Répertoire national des élus: les maires" (in French). data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises. 13 September 2022.

- "Populations légales 2020". The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. 29 December 2022.

- Comparateur de territoire: Aire d'attraction des villes 2020 de Nice (017), Unité urbaine 2020 de Nice (06701), Commune de Nice (06088), INSEE, retrieved 20 June 2022.

- Demographia: World Urban Areas Archived 7 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Demographia.com, April 2016

- Ruggiero, Alain, ed. (2006). Nouvelle histoire de Nice. Toulouse: Privat. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-2-7089-8335-9.

- Alain Ruggiero, op. cit., p. 137

- "Nice, France travel. Comprehensive guide to Nice". Europe-cities.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- "Southern French city of Nice earns UNESCO world heritage status". France 24. 27 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- Un savoir-faire et un équipement complet en matière d'accueil, Urban community of Nice Côte d'Azur website Archived 24 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Les chiffres clés du tourisme à Nice, site municipal Archived 17 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Union des aéroports français – Résultats d'activité des aéroports français 2007 – Trafic passagers 2007 classement – page 8" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Nice". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 646–647.

- "Le Nouveau venu" (in French). Musée de Paléontologie Humaine de Terra Amata. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- A. G. Wintle; M. J: Aitken (July 1997). "Thermoluminescence dating of burnt flint: application to a Lower Paleolithic site, Terra Amata". Archaeometry. 19 (2): 111–130. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1977.tb00189.x. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- "The Chsteau of Villeneuve-Loubet". Villeneuve-Loubet Guide and Hotels. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- Ruggiero, Alain (2006). Nouvelle Histoire de Nice (in French).

- Kendall Adams, Charles (1873). "Universal Suffrage under Napoleon III". The North American Review. 0117: 360–370.

- Dotto De' Dauli, Carlo (1873). Nizza, o Il confine d'Italia ad Occidente (in Italian).

- Large, Didier (1996). "La situation linguistique dans le comté de Nice avant le rattachement à la France". Recherches régionales Côte d'Azur et contrées limitrophes.

- Paul Gubbins and Mike Holt (2002). Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe. pp. 91–100.

- Peirone, Fulvio (2011). Per Torino da Nizza e Savoia. Le opzioni del 1860 per la cittadinanza torinese, da un fondo dell'archivio storico della città di Torino (in Italian). Turin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ""Un nizzardo su quattro prese la via dell'esilio" in seguito all'unità d'Italia, dice lo scrittore Casalino Pierluigi" (in Italian). 28 August 2017. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- "Nizza e il suo futuro" (in Italian). Liberà Nissa. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- Courrière, Henri (2007). "Les troubles de février 1871 à Nice". Cahiers de la Méditerranée (74): 179–208. doi:10.4000/cdlm.2693.

- Paul Gubbins and Mine Holt (2002). Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe. pp. 91–100.

- "Il Nizzardo" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- "Un'Italia sconfinata" (in Italian). 20 February 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- "Nice Grand Prix". Best of Nice. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Léon Poliakov, La conditions des Juifs sous l'occupation italienne, Paris, CDJC, 1946 and bibliographies of Angelo Donati and Père Marie-Benoît

- Pogatchnik, Shawn (23 May 2002). "Irish referendum on Nice Treaty 'doomed to fail again'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Almasy, Steve (14 July 2016). "Nice mayor: 'Tens of dead' when truck runs into crowd". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- "Nice truck attack claims 86th victim". Star Tribune. 19 August 2016. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- "Nice attack: At least 84 killed during Bastille Day celebrations". BBC News. 15 July 2016. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Duffield, Charlie (14 July 2020). "Nice attack: What happened in the 2016 Bastille Day killings". www.standard.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- Gaillard, Eric (29 October 2020). "Three dead as woman beheaded in knife attack at French church". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Tidman, Zoe (29 October 2020). "Nice stabbings: Woman decapitated and others killed in France knife attack". The Independent. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Nash, Dennison (1979). "The rise and fall of an aristocratic tourist culture: Nice: 1763–1936". Annals of Tourism Research. 6 (1): 65. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(79)90095-1.

- Mitchell, L.G. (1994). "Voyages au pays des mangeurs de grenouilles: La France vue par les Britanniques du XVII siecle a nos jours". The English Historical Review. 109 (433): 1018. doi:10.1093/ehr/CXI.433.1018. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Ralph Schor (Edited by), Dictionnaire historique et biographique du comté de Nice (Historical and biographical dictionary of the County of Nice), Nice, Serre, 2002, ISBN 978-2-86410-366-0, pp.22–23 (in French)

- "French Riviera hit by snowfall Archived 12 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine". The Local fr. The Local Europe AB. 26 February 2018.

- "Nice (06)" (PDF). Fiche Climatologique: Statistiques 1991–2020 et records (in French). Meteo France. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- "Nice, France – Climate data". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- "Nice (07690) – WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Normes et records 1961–1990: Nice – Côte d'Azur (06) – altitude 4m" (in French). Infoclimat. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- "Technology Parks to promote regional economic transformation | Interreg Europe – Sharing solutions for better policy". www.interregeurope.eu. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- "Global city GDP 2011". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "French Riviera train for Russia". BBC News. 23 September 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- "Dates et chiffres clés / La ligne 1 / Accueil – Tramway de la Communauté Urbaine Nice Côte d'Azur" (in French). Tramway.nice.fr. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "Olympic Nice Natation homepage" (in French). Olympic Nice Natation. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Nice, EHESS (in French).

- Population en historique depuis 1968 Archived 10 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, INSEE

- Nice – French Riviera: Noon on the Dot from francemonthly.com. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Jack, Albert (2010). What Caesar Did For My Salad: The Secret Meanings of our Favourite Dishes. London: Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141929927.

- "Villes jumelées avec la Ville de Nice" (in French). Ville de Nice. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- "Astana and Nice established twin relations". Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- "Twin and Partner Cities". City of Edinburgh Council. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- "British towns twinned with French towns [via WaybackMachine.com]". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- "City of Locarno – Twin Towns & Sister Cities". Archived from the original on 10 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "Netanya – Twin Cities". Netanya Municipality. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- "Twinnings" (PDF). Central Union of Municipalities & Communities of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- "Yerevan – Twin Towns & Sister Cities". Yerevan Municipality Official Website. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- "René Cassin". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Lichfield, John (9 October 2008). "French novelist Le Clézio wins Nobel literature prize". The Independent. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- General Michel Franceschi (Ret.), Austerlitz (Montreal: International Napoleonic Society, 2005), 20.

- Jazzophone Archived 29 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 19 December 2016 (in French).

- "Biography". Robert W Service Estate. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- Musée de l'Ordre de la Libération. "Aimé Teisseire" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 19 January 2016 (in French).

- "Prince Charles made honorary Niçois". Connexionfrance.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

Further reading

- Sykes, Colonel. "Statistics of Nice Maritime." Journal of the Statistical Society of London 18.1 (1855): 34–73. online

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

- Official website of the City of Nice (in French)

- Official website of Nice Metropolis (in French)

- Nice, Winter Resort Town of the Riviera UNESCO collection on Google Arts and CultureNice at Curlie